On the 2nd of March 2018, I defended my thesis titled Values of Craft: the Indian case at Erasmus University, The Netherlands. My thesis, seven years in the making, has been a transformative process that made me question the appropriateness of our current economic understanding of crafts. It made me think about what the appropriate economic framing lenses are through which we can make sense of the crafts. I hope to share with you my experience and key findings through a series of four articles that will take you through my journey of discovery and perhaps offer a new way of making sense of the crafts sector.

Let us begin with the acknowledgement that crafts sector the world over is receiving renewed attention. Some authors like Susan Luckman (Luckman, 2015, p. 12) are even calling it as being part of a third wave in the revival of interest in crafts. This is happening in conjunction with at least few other parallel movements: the Do it Yourself movement as well as the Maker movements along with advent of new technologies like 3D printers and a understating that we are on the cusp of the fourth industrial revolution where human creativity is a valuable resource makes us pay attention to crafts and try and make sense of it

What makes this story interesting is that the treatment of crafts across countries varies this fact becomes evident in the seven-nation study of crafts. In the Asian context, the three countries that were chosen for comparison were India, China and Japan. The similarities in these three countries were that they are all ancient civilisations, have very distinct cultures and practices, and are traditional societies. However, of the three, India and China are emerging economies, where China is leading in the manufacturing sector, while India enjoys a favourable position in the service sector. Japan, on the other hand, is one of the most advanced economies in the world and enjoys a reputation as being a leader in technology and precision work.

This is in contrast to the other countries that were part of the research. While Germany, Italy, the UK and the Netherlands are all advanced economies, Italy bears the distinction of being the most traditional of this grouping. Germany has the reputation for engineering while Italy is well known for design and art.

The UK, on the other hand, is, or rather was, the only country to have crafts as part of its idea of the creative economy in the DCMS model (Potts, 2008). Germany, Japan, Italy, India and China are well known for craft production, though they differ on an important point. India and China are recognised for selling crafts objects while, Germany, Japan and Italy sell the idea of quality, precision and the intangibles of craftsmanship.

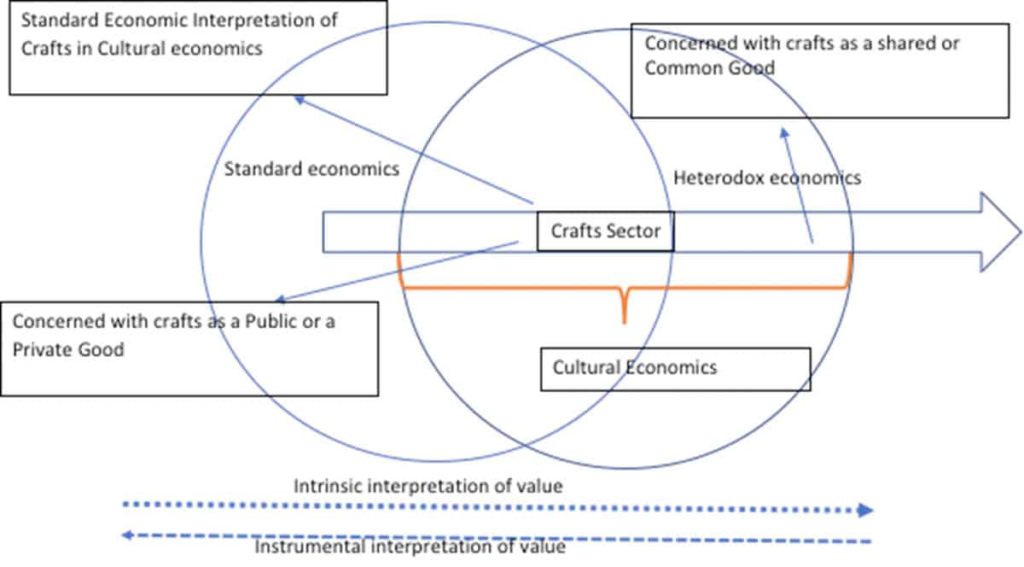

During the study what also became evident is that the economic lens through which we make sense of the world of crafts is what we understand as a standard economic approach. Neo-classical economics forms the orthodoxy of the economics which is decidedly modernist in its outlook and follows ten dictums (McCloskey, 1983) in order to dress economics up as a science. This version (Boland, 1991) of economics is centred on the rational economic man and his self-interest for profit maximization as a determinant of economic behaviour. This we label as the standard economic perspective. This version of economics is what I understand to be an instrumental approach to economics which is reductionist in nature and is concerned with what can be easily quantifiable. This produces a view about the sector that is concerned with issues of efficiency, productivity, contribution to the GDP. The goods produced in such a worldview seek markets for consumption of private goods and when there exists market failure, public intervention is sought as a solution to safeguard our culture and heritage. This economic lens applies instrumental logic onto a sector that predates the industrial revolution and is an expression of human creativity, skill and culture.

At this point, there is something to be said for the semiotic relationship between definitions and economic approaches to study crafts. I claim that instrumental definitions lead to an instrumental economic approach to understanding the sector and visa versa. This claim was substantiated in a recent In an international symposium organised at Erasmus University titled Values of Craft: Craft as Intangible Heritage where various aspects about the nature of crafts were discussed. In this context, there was an effort to make sense of crafts in terms of national and international definitions. What emerged is that definitions exist with the idea of exclusion of items as opposed to being inclusive. This principle allows policy planners to define crafts by virtue of its meeting the criteria to obtain certain subsidies and protection. As evidenced by the presentation of Francesca Cominelli, the urgency of defining crafts is a governmental issue, for the purpose of getting good statistics and setting a basis for policy. This aspect emerged also from the presentation of the Japanese case from Kazuko Goto who, acknowledging that budget constraints limit the list of Living Heritage, underlined the need of definitions to be able to have access to funds.

To expand our conversation further about the economics of crafts let us consider the image below. It’s a patch of embroidery work which is common to the nomadic tribes of India who very often embellish their cloths with very intricate needlework and also integrate coins into the weaving which is one of the distinguishing features of this kind of work.

This image conveys meaning at many levels which do justice to our current conversation about applying various economic lenses to understand crafts and to move from an instrumental to an intrinsic understanding of the values of craft. At a cursory glance, the image is unmistakably craftwork, but it has layers of meaning that are associated with it, which depend upon one’s immersion and participation into the culture that surrounds its production and consumption. For a casual consumer, it might hold just as aesthetic value for which he or she is willing to pay a price in a market where equally beautiful crafts objects are fighting for attention. However, it can also be way more than that for those who are immersed in the crafts culture of its production and consumption where various social, societal, personal and in some cases transcendental values are exchanged between the user communities, user communities, user and maker communities and the maker communities.

In other words, we can think of crafts as a shared practice where common goods are co-produced. What I find peculiar then is the fact that when we do the economics of crafts the shared goods nature of crafts is obscure in the conversation as the standard economic perspective cannot account to these intangibles of culture as a factor for human economic behaviour. Developing an economic understanding of crafts as shared practice then became the subject of conversation in where we move away from an instrumental understanding of values of crafts (such as price, employment, contribution to GDP and so on …) to an intrinsic sense-making of the values of crafts and its contribution.

In this quest to understand the intrinsic value of craft we are in need of a heterodox approach to the economics of craft. In this new conversation, the economics of craft are concerned with understanding the crafts to be producing shared and common goods as opposed to public or private goods in the case of the standard economic perspective. However before we explore this new economic perspective on crafts, we will first explore crafts using the standard economic perspective with the crafts sector in India as a case. This will be the subject of our next article.

The study explored the craft economies of England, Japan, Germany, China, India, Italy and Holland. The crafts research Group that undertook the study included Prof. Kazuko Goto, Asst Prof. Anna Mignosa, Lili Jiang, Thora Felljested and me (Priyatej Kotipalli ), and was led by Prof Arjo Klamer.

Bibliography

Boland, L., 1991. Current views on economic positivism. Companion to contemporary economic thought, pp. 88-104.

Luckman, S., 2015. Craft and the creative economy. s.l.: Springer.

McCloskey, D., 1983. The rhetoric of economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 21(2), pp. 481-517.

Potts, J. a. C. S., 2008. Four models of the creative industries. International journal of cultural policy, 14(3), pp. 233-247.

Author

Priyatej Kotipalli holds a PhD in Cultural Economics from Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. His primary research interest is in the economics of intangible cultural heritage with a special focus on traditional knowledge and skills. He serves on the board of various cultural organisations in the Netherlands and India. He is also a member of the National Scientific Committee of Intangible Cultural Heritage, ICOMOS India, and of the Crafts Council of Telangana, India.

Priyatej Kotipalli holds a PhD in Cultural Economics from Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. His primary research interest is in the economics of intangible cultural heritage with a special focus on traditional knowledge and skills. He serves on the board of various cultural organisations in the Netherlands and India. He is also a member of the National Scientific Committee of Intangible Cultural Heritage, ICOMOS India, and of the Crafts Council of Telangana, India.

Comments

Good Insight!