Liz Williamson (1949-2024), Weaving Eucalyptus Project (2020-21), silk dyed by artists in Australia, India and Bangladesh with locally sourced eucalyptus leaves, bark or twigs; silk hand-woven as weft into a linen and cotton warp, 73 panels (installed dimensions variable). Courtesy of the artist’s estate. Installation view from Radical Textiles. Photo: Saul Steed

Inga Walton reviews an exhibition curated by the late Liz Williamson that showcased the unique language of textiles.

The career and legacy of renowned textile artist Liz Williamson (1949-2024), who was also the Honorary Associate Professor, University of New South Wales Arts, Design & Architecture, continues to reverberate within the artistic community to which she devoted so much of her life.

Sometimes referred to as the “matriarch of Australian weaving”, Williamson was the fourth artist selected in the Australian Design Centre’s Living Treasures: Masters of Australian Craft series. The survey exhibition of her work toured to fourteen galleries across five states and one territory from 2008 to 2011. The accompanying book, Liz Williamson: Textiles (2008), by Grace Cochrane, chronicled Williamson’s career achievements, but was significantly out of date at the time of her death.

Williamson’s last large-scale work, the Weaving Eucalyptus Project (2020-21), was included in the recent survey exhibition Radical Textiles (23 November 2024-30 March 2025) at the Art Gallery of South Australia. The project began in November 2019 with an invitation from Dr Kevin Murray to participate in the exhibition Make the World Again of contemporary Australian textiles, intended for Crafted Vancouver in May 2020. The pandemic intervened, and the project was eventually staged online, hosted by the Australian Tapestry Workshop (1 December 2020-4 March 2021).

In 2020, Williamson invited colleagues in Australia and India to participate in the project to colour undyed silk she had prepared with eucalyptus leaves endemic to the local environment, and return it to her. In 2021, the project was expanded to include representation from countries in the range of the Indian Ocean where the dispersal of the species had occurred: Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, Madagascar, Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka, South Africa and Thailand. Before her death, further contributions from Australia and New Zealand were woven.

The resulting panorama of cascading panels with locally extracted dye also conveys a subtle message about permaculture and the sustainability of a potential eucalypt dye industry amidst the preference for chemical dyes. This collaborative project drew on Williamson’s strengths as a facilitator, mentor and advocate. She created opportunities that demonstrated, in a meaningful way, how universal textile traditions, cultural connections, and the opportunity to consolidate skills through exchanging experiences could achieve a coherent expression.

UNSW Galleries toured the Weaving Eucalyptus Project to five regional galleries in Victoria and New South Wales (2022-24), including Ararat Gallery/TAMA (4 March – 18 June 2023). During that time, Williamson and Katy Mitchell, the Visual Arts Coordinator at TAMA, discussed Williamson’s interest in continuing her exhibition Weaving matter: materials and context (30 March – 7 June 2023) that had been staged at the Australian Design Centre, Sydney. The exhibition was a response to the influential German artist, weaver and designer Anni Albers (née Annelise Fleischmann, 1899-1994), whose writings, particularly the seminal On Weaving (1965), had a profound effect on subsequent generations in terms of how artists pursued the creative process. An essay by Albers, “Material as metaphor” (1982), was the starting point for Williamson, specifically the quote, “To make (our ideas) visible and tangible, we need light and material, any material. And any material can take on the burden of what has been brewing in our consciousness or subconsciousness, in our awareness or in our dreams.”

Williamson approached artists who were experimenting with different materials, how the attributes of those materials were conveyed, and creating work with interesting or challenging concepts. She was interested in those translating contemporary, political, social, personal or environmental themes into works that were not necessarily functional. The first exhibition brought together works by Christine Appleby, Sally Blake, Mary Burgess, Hannah Cooper, Blake Griffiths, Amanda Ho, Lise Hobcroft, Kelly Leonard, Jennifer Robertson, Nien Schwarz, Jacqueline Stojanović, Jane Théau, Ilka White, and Monique van Nieuwland.

Following Williamson’s death, the show was revisited and expanded by Mitchell as Weaving Matter: Material Experimentation (12 October 2024-16 February 2025). Introducing the exhibition, Mitchell remarked, “With the support of Liz’s family and the exhibiting artists, we proceeded with exhibition preparations in Liz’s honour. Liz was a dedicated supporter of Ararat Gallery/TAMA, with a long history as an exhibitor here, and she was a champion of our specialisation in textiles and fibre. In the time that I have been in this role, Liz has been a generous and kind collaborator and mentor. I will miss her greatly and I have mourned her absence in preparing for this exhibition…”

Jane Théau, Annelida (2024), horsehair weft, copper warp. Conflagration, Regeneration (2023), horsehair weft, cotton warp, 100 x 40 cm (approx). Collection of Liz Williamson. Photo: Inga Walton

Eleven of the original artists were included, with the works installed in the smaller Peggy & Leslie Cranbourne Gallery within the Ararat Gallery complex. The multi-disciplinary practice of Dr. Jane Théau encompasses sculpture and installation, community art projects and collaboration with performance artists. Her recent works in horsehair are a response to the catastrophic Black Summer bushfires (2019-2020), during which her house was surrounded by the fire front. “The bush for miles around was incinerated, and the aftermath was devastating. The trees that survived sprouted voluminous skirts of vivid lime- and emerald-green regrowth: the precise green of some horsehair I had dyed”, Théau recalls.

The work Conflagration, Regeneration (2023) is woven with bursts of green to symbolise the first shoots of new growth, and was acquired by Williamson from the first iteration of the exhibition. “Horsehair has a unique tactile quality that I think talks to our skin, because it is a product of skin. It also has a beautiful translucency when woven. The green horsehair…became this work, a homage to the resilience and optimism of the trees that survived the conflagration”, Théau comments. For the larger piece, Annelida (2024), Théau has used copper as a warp to provide a manipulable scaffold for the more pronounced sculptural aspect.

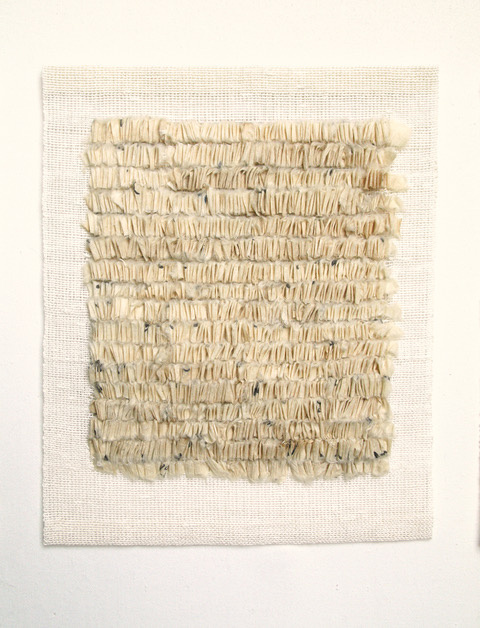

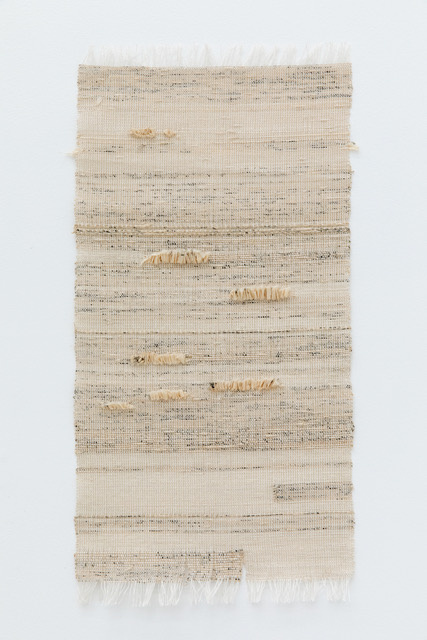

- Amanda Ho, Script (2024), linen warp with hand spun paper, 27.5 x 22.5 cm

- Amanda Ho, Script – Characters (2024), linen warp with hand spun paper.

- Amanda Ho, Script – Cursive (2024), linen warp with hand spun paper, handmade paper waste.

- Amanda Ho, Study in Shifu IV (2023), linen warp with hand spun paper, 50 x 25.5 x 1 cm.

Of Chinese background, Amanda Ho spent part of her childhood in Hong Kong. While working as an architect, she studied weaving, and this is discernible in the design, materials, patterns and structures within her work. Ho’s weaving practice has been greatly inspired by the philosophy of artist, curator, and textile researcher Yoshiko Iwamoto Wada, an exponent of the Slow Fiber movement. After studies in Japan, Ho became interested in the tradition of paper yarn, specifically the method of Kami-ito, turning washi (Japanese paper) into threads. Her work shows the effects of combining different thicknesses, textures, and evenness of hand during spinning using a combination of up-cycled and new paper, simple weave structure and remnants of the handmade paper. In this way, Ho rehabilitates paper in the viewer’s mind as something with the potential to be strong, resilient, and even waterproof when treated with konyaku (the starch-like substance found in root vegetables).

Study in Shifu IV (2023) hearkens back to a time in Japan when clothing for those at the lower socio-economic scale was made from fibres such as hemp, flax and ramie. Silk was introduced around 600 BC- 200 AD, but for a long time, its use was restricted to the upper classes and royalty. Cotton was not introduced until around 1573-1603, and wool was not in common usage. Ho rediscovers paper as a valuable fabric, but also reflects on paper as a lost vehicle of communication in the digital age, with handwriting and calligraphic skills falling into disuse. She cuts up old books to make paper yarn, the linear compositions evoking ancient texts where language is embedded with image and code that we no longer recognise.

- Christine Appleby, Balance Maquette I (2024), hand-woven, stainless steel and copper wire on Perspex, 20 x 32 x 3. Photo: Inga Walton

- Christine Appleby, Bombo (2023), hand-woven, basalt, cotton, nylon, paper, stainless steel wire, velvet and wool on Perspex, 40 x 65 x 15 cm.

Christine Appleby’s work responds to the Bombo Headlands Geological Site, a heritage-listed former basalt quarry located on the south coast in the Illawarra region of New South Wales. Her interest in capturing imperfection and irregularity within the environment was well served by the natural and industrial history within this landscape. The interlaced Balance Maquette I (2024) and the undulating Bombo (2023) experiment with stainless steel and copper wire. Bombo was woven flat utilising combinations of weave structures, from tight to dense and an unusual assortment of fibres, including basalt. The wall-mounted Igneous Maquette I (2024) and the free-standing group Igneous Maquette II (2024) reference the fortress-like natural structures, and the contrasting colours of the red-brown sandstone (due to oxidation of haematite) and the grey-black latite (volcanic rock).

Based at Broken Hill, Kelly Leonard also explores the impact of industry in her work, in this case, extractive mining conducted on the site of this polymetallic ore body, including cobalt, Sphalerite, iron ore, Galena, and Argentite. Leonard uses fieldwork as her primary methodology to interact with the environment, and to record sounds, installations and performative actions for audiences. As a teenager, Leonard was taught hand-loom weaving by a second-generation Bauhaus weaver, Marcella Hempel, in Wagga Wagga. She produces floor loom-based textiles with found or recycled materials. In the case of the two-part Transmission (2024), Leonard has inserted small pebbles of quartz into pockets held within the work. She incorporates recycled bell wire (used to set the explosives underground) to weave ‘conductive ribbons’ (the wire has a copper core). The wire acts as a ‘receiver’ for the inherent ‘energies’ transmitted from the environment when the artist uses a field recorder.

Jacqueline Stojanović, Fontana (2022), handwoven silk velvet on MDF, 24 x 24 cm. Diptych VI (2022), wool, cotton, linen, 60 x 60 cm. Photo: Inga Walton

Jacqueline Stojanović met Williamson in 2022 at the opening of the UNSW Galleries touring exhibition Pliable Plains: Expanded Textiles & Fibre Practices (2022-24), in which her work Concrete Fabric (2019) was included. Stojanović credits Williamson with encouraging her to work with jacquard weaving, which she pursued at the Fondazione Lisio in Florence, Italy. The sample Fontana (2022), was woven on an early 20th century Jacquard velvet loom and named after the Tagli (Cuts) series (1958-68) of slashed monochrome paintings by Lucio Fontana (1899-1968). Created as a draft while Stojanović was learning the punch card system, the work merges two separate designs, which are exemplars of monochrome and polychrome punch cards. During a residency at Lottozero in Prato, Italy, Stojanović commenced a series of ‘fabric paintings’ of which Diptych VI (2022) is part. These were woven from a collection of Italian crossword puzzle patterns she purchased from local newsstands, which have been interpreted as weaving drafts for a countermarch loom.

Blake Griffiths, Vaðmál, study 1 (2023), linen, Icelandic wool, wax, 220 x 33 cm. Vaðmál, study 2 (2023), Icelandic wool, earth pigment, wax, 240 x 33 cm. Photo: Inga Walton

Blake Griffiths worked with Williamson in her studio and considered her a mentor, “Liz was always the pathway forward, actually, for many people in the textile community, because no one else could kind of keep a community going in the way Liz managed to”, he contends. Suspended over an access door, two wool banners, Vaðmál, study 1 and study 2 (2023) were created using a Vefnaður (Broken Twill) draft, digitised by the Icelandic Textile Centre in Blondous. Griffiths uses a floor loom to transform materials and respond to place-specific textile histories. These works continue his investigation of ancient Viking cloth-making techniques, such as smörring, which involves treating woven cloth with a mixture of native earth, pigment, animal fat, oil and water.

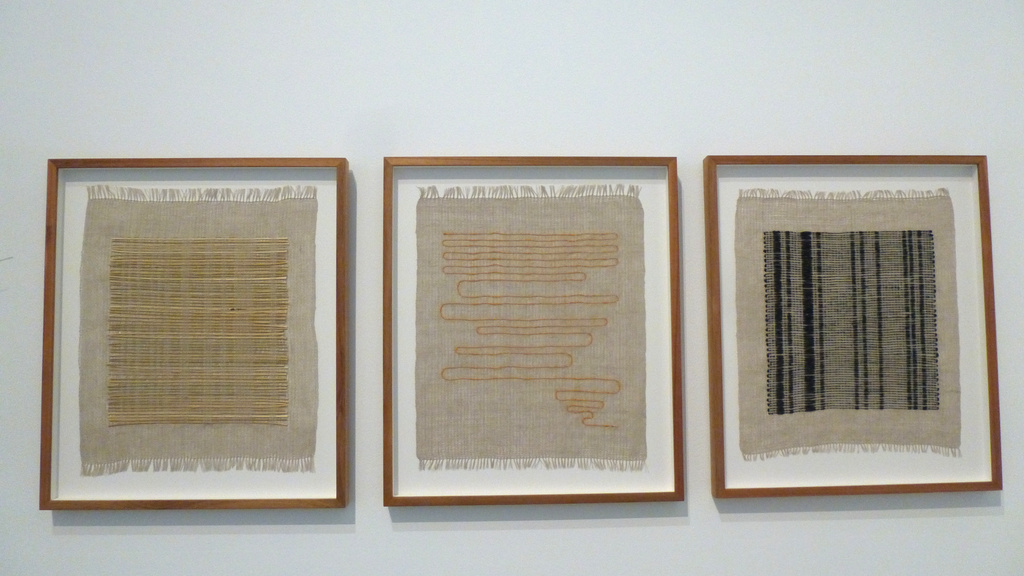

- Lise Hobcroft, Plant II (2024), lomandra (native grass) on linen. Paper II (2024), paper string on linen. Plastic II (2024), single use plastic on linen, (all) 47.6 x 43.1 cm (framed). Plant, Paper, Plastic II series. Photo: Inga Walton

- Lise Hobcroft, Plant (2023), lomandra (native grass) and cottolin, 65 x 20 x 14 cm. Paper (2023), eri silk and paper string, 19 x 18 x 14 cm. Plastic (2023), eri silk and single use plastic bag, 16 x 20 x 80 cm. Single Use series. Photo: Inga Walton

The predominant themes in the work of Lise Hobcroft are sustainability, repurposing and reusing waste, and prioritising the use of native Australian flora and fauna across hand-woven domestic textiles, basketry, knotted rope works and large-scale installations. The Single Use series, including Plant, Paper, and Plastic (2023), addresses ‘greenwashing’ and presents reusable solutions to single-use plastic bags utilising the materials referenced in the work’s titles. This is continued in the Plastic II series (2024), where the Australian native grass lomandra is again utilised.

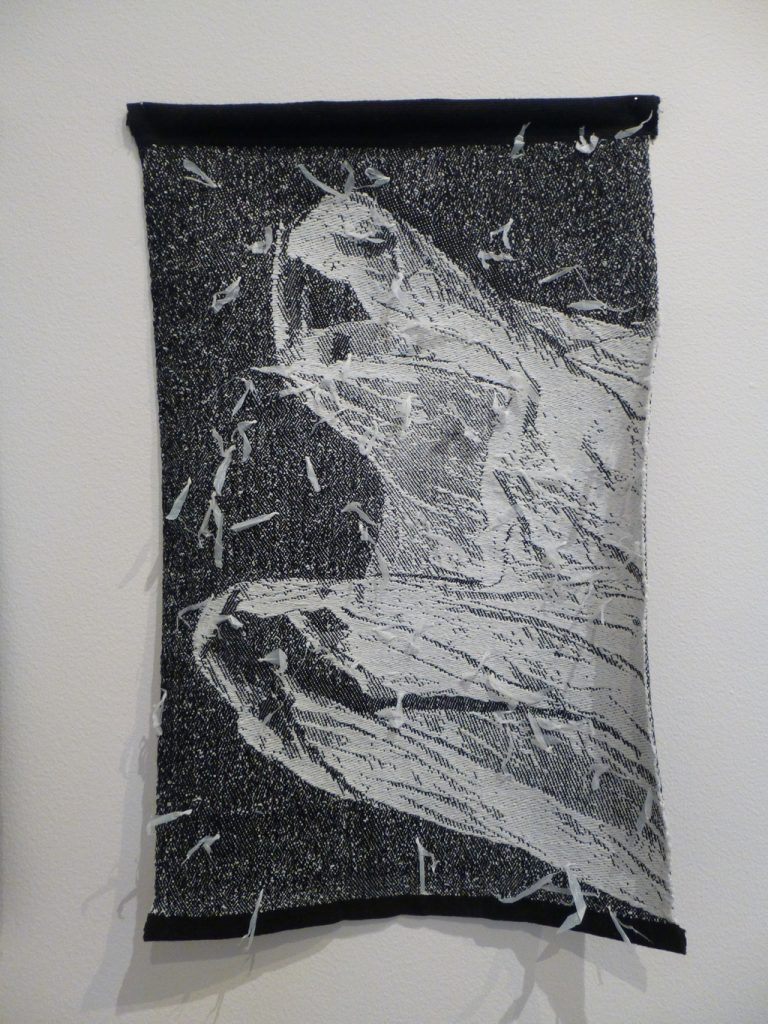

- Monique van Nieuwland, Chucked (2023), linen warp, stainless steel weft, hanging tube, handwoven Jacquard, 54 x 37.5 cm. Tossed (2023), linen warp, cut up potato chips bags weft, hanging tube, handwoven Jacquard, 55 x 36 cm. Blown (2023), linen warp, cut up plastic shopping bag weft, hanging tube, handwoven Jacquard, 52.5 x 36 cm. Lost (2023), linen warp, cut up face mask material weft, hanging tube, handwoven Jacquard, 55 x 37 cm. Photo: Inga Walton

- Monique van Nieuwland, Tossed (2023), linen warp, cut up potato chips bags weft, hanging tube, handwoven Jacquard, 55 x 36 cm. Photo: Inga Walton

Monique van Nieuwland was the Workshop Technician during the time Williamson was a Lecturer at the Textiles Workshop (1991-96), Canberra School of Art, at the Australian National University. Van Nieuwland’s work focuses on the environment, the waste generated by our daily lives, and thoughtless behaviour. The quartet Chucked, Tossed, Blown and Lost (all 2023) and the companion work Littered (2023) incorporate rubbish, a realisation that sometimes startles viewers.

The artist cuts up discarded items such as potato-crisp bags, single-use plastic bags, and the ubiquitous face masks of the pandemic period, combining them with linen to create socially responsive works. “I wasn’t necessarily working with ready-made yarns or materials produced already for me. I had to source, and for these works I was looking at rubbish”, van Nieuwland explains. “So literally everyday I looked at my surrounds around the dog park, and I picked up four things just like that that I could turn into weaving but I had to listen to the material, what it would do…”

Monique van Nieuwland, Fast Fashion Strata (2024), linen warp, Weft: recycled fast fashion rag strips weft, rust/compost/natural dyes, discontinued weft, handwoven Jacquard, 125 x 36 cm. Wasteland Strata (2024), linen warp. Weft: recycled fast fashion rag strips, metal, plastic, electronic waste, rope, netting and paper, rust/compost/natural dyes, discontinued weft, handwoven Jacquard, 125 x 36 cm. Photo: Inga Walton

The longer, paired works, Fast Fashion Strata and Wasteland Strata (both 2024), are critical of mass production practices that result in an oversupply of poor-quality clothing that is later discarded in pursuit of newer trends. Unchecked consumerism results in countless garments going to landfill, and the exploitation of garment workers in developing countries. The choice of materials and their significance are essential to van Nieuwland in creating an artistic voice that will convey the design concept. “As weavers, we have to respond. Things have functions, and functional weaving for domestic textiles has always been about what will the end result be, what will it do, does it need to absorb, does it need to stop light coming through. So weavers are in tune with what the thread or the material can do.”

Hannah Cooper, Warping the Weft (after glass) 1 (2023), fishing line and vintage Japanese gold-leaf thread, Perspex, 25 x 30 cm. Warping the Weft (after glass) 2 (2023), fishing line and synthetic metallic embroidery thread, 23 x 23 cm. Photo: Inga Walton

Illuminated by the light coming from the window space, Hannah Cooper’s two-part hanging fabric work Warping the Weft (2024) channels light movement through a pliable surface, an additional shimmer coming courtesy of the competing gallery lights. It was Cooper’s intention to weave a weft of glass rods through a warp of transparent fishing line. Through the weaving process, the fishing line did not remain static or stable when removed from the loom’s tension; the artist pivoted her approach, changed her weft and embraced the fluidity of the warp. These experiments have led the artist to a new concept for future projects, embracing a warping of the weft.

Cooper is self-taught and started weaving in 2017, teaching herself on a rigid heddle loom and concentrating on the textural possibilities within plain weave. She focuses on traditional cloth-making techniques to produce domestic textiles, which she believes are deeply undervalued in our daily lives. Cooper now weaves on a manual 12-shaft countermarch floor loom, utilising more complex structures; she dyes thread naturally with plants and insects for use in her artworks. Nearby, the framed Warping the Weft (after glass) 1 (2023), and the companion Warping the Weft (after glass) 2 (2023), demonstrates the use of gold-leaf thread as weft, relying on the fishing line warp that can hold its form off the loom.

Ilka White, From my selves (2023), native flax (Linum Marginale), artist’s hair, 60 x 16 x 5 cm. Core (care) sample (2024), locally grown native flax and banana fibre, artist’s hair, vintage sewing thread, commercial yarn scraps (cotton, linen and wool), 70 x 10 x 10 cm. Gaza Kite (for Refaat Alareer) (2024), home grown Muka (extracted from Harekeke, New Zealand Flax), 60 x 80 x 1 cm. Photo: Inga Walton

Ilka White’s works utilise fibre from her garden, yarn scraps from a recent commission, and her own hair to produce three very different suspended works. The artist has stated, “Right now I’m drawn to anything that reaffirms human connection to our miraculous ecosystem… As I gathered, spun and wove, I thought about plant and animal interactions, shamanic protections and weavers of other species. I gave thanks for opposing thumbs, patchwork and traditions of ‘making do’. I contemplated the Fibreshed movement, community sufficiency, order and chaos, post-oil futures and deep time.”

Jennifer Robertson, Viscoelasticity (2024), carbon fibre/poly, lacquered paper, resin, 142 x 24 x 13 cm. Photo: Inga Walton

Positioned next to White’s works in the space, Jennifer Robertson’s wall-mounted pieces employ the latest technologies in fibre weaving using a fourteen layered warp on a digital handloom. Counterintuitively, Tree Skin II (2023) uses inorganic fibres and metals to mimic the tactile language of creases and folds synonymous with bark.

Fourteen tiny shuttles were used to create Viscoelasticity (2024) in one piece on the loom, each layer woven one weft row at a time. On the loom, the work looked like a flat-packed weaving of many layers; when cut off the loom, the work fanned out, similar to uncut book pages.

The Weaving Eucalyptus and the Weaving Matter projects are emblematic of Williamson’s commitment to craft dialogue and sustained contribution to creative life in Australia. Both exhibitions speak to her engagement with practitioners from the Australian and international community of makers, forging strong professional ties over decades of determined advocacy and exchange. Williamson’s passion for the textile medium will be greatly missed; her considerable body of work will endure. However, it is with the cohort of younger artists she worked with and encouraged, in Australia and internationally, where her powerful example will continue to resonate, just as Anni Albers’ work remains a touchstone.

✿

Weaving matter: material experimentation, Ararat Gallery/TAMA, 12 October 2024 – 16 February 2025

Liz Williamson’s work is included in 50 Plus: Celebrating 50 years of Tamworth Regional Gallery’s Fibre Textile Collection (until 20 July 2025), also at TAMA.

About Inga Walton

Inga Walton is an arts writer, editor and consultant based in Melbourne, Australia, who writes widely about fine arts, fashion and textiles, film, and popular culture. Her work has appeared in over thirty Australian and international publications; she has authored numerous catalogue entries and essays and contributed to several books.

Inga Walton is an arts writer, editor and consultant based in Melbourne, Australia, who writes widely about fine arts, fashion and textiles, film, and popular culture. Her work has appeared in over thirty Australian and international publications; she has authored numerous catalogue entries and essays and contributed to several books.