Diane Moon and Will Stubbs describe the exchange between Yolŋu and Makassan cultures that continues after their trade was banned.

Despite the cessation of trade in 1906, cultural exchange between Yolŋu and Makassan has continued into the twenty-first century. In the Yolŋu / Macassan Project, the tenth Asia Pacific Triennial featured powerful works that speak to the continuing deep connection between the two ancient cultures of Australia and Indonesia. Diane Moon and Will Stubbs write about the works by Nawurapu Wunungmurra, Margaret Rarru and Gunybi Gununmbarr.

Diane Moon introduces the project:

Legacy of contact

The Yolŋu/Makassan project responds to the cultural, social and spiritual connections between the salt-water Yolŋu of north-eastern Arnhem Land and Makassan and Bugis boat-builders, traders and fishers of south Sulawesi in the Indonesian archipelago—a rich relationship of mutual respect lasting hundreds of years until South Australian Government intervention in 1906 banned the interaction.

Yolŋu and Makassan coexistence was peaceful and convivial. Over the months-long annual visits to Arnhem Land (Marege) they worked side by side, harvesting and processing darripa (trepang) a delicacy supplied to Chinese traders. The more intrepid Yolŋu even took the return journey to Sulawesi on the sailboats. Yolŋu seamanship was learnt from Makassans and only a generation or so ago they still travelled the coastline in lipalipa (dugout canoes) made using steel axes from a single tree trunk and rigged with dhomala (Makassan-style woven sails).

Makassan words are in daily use by Yolŋu and are performed in ancient songlines of the Dhalwaŋgu, Gumatj, Munyuku and Rirratjingu clans. Some of these poetic chants celebrate the early rising clouds on the horizon, equivalent to the first sightings for the year of the Makassan perahu (appearing like clouds) under sail with Luŋgurrma (the northerly monsoon winds of the approaching Wet season)—an analogue of the rebirth of the spirit after death rituals. Other songs lament the setting of the sun, which correlates to both the passing of a loved one and Yolŋu grief felt when the sailors raised their masts and returned to Sulawesi with Bulungu (the south-easterly winds of the early Dry season).

The powerful installation of larrakitj memorial poles by Yirrkala artist Nawurapu Wunungmurra (1952- 2018), installed in a configuration reminiscent of a Makassan perahu, affirms the legacy of the contact, reiterated still in Yolŋu mortuary ceremonies. Yolŋu and Makassan-crafted woven sails, bark paintings with Makassan references and a collection of ceramic bottles, water and storage pots made in Makassar and painted in Yirrkala expand on the narrative. The ceramics sit amidst pottery shards (some ancient, found on remote Yirrkala beaches) as irrefutable evidence of the Makassan presence in the region. In, and through this exhibition the spirit of the ancestral connections is renewed and celebrated.

Text from the 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art

About Diane Moon

After working with artists in Arnhem Land from 1983 to 1994 and then as an independent curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art, since 2003 Diane Moon has been at the Queensland Art Gallery as Curator Indigenous Fibre Art. Upcoming project opening in August at GOMA is Transitions: Historic and Contemporary Barks from the Collection 1948-2021 / Transitions now: Contemporary Aboriginal Forms and Images from the Collection.

Will Stubbs writes about the individual artists:

✿

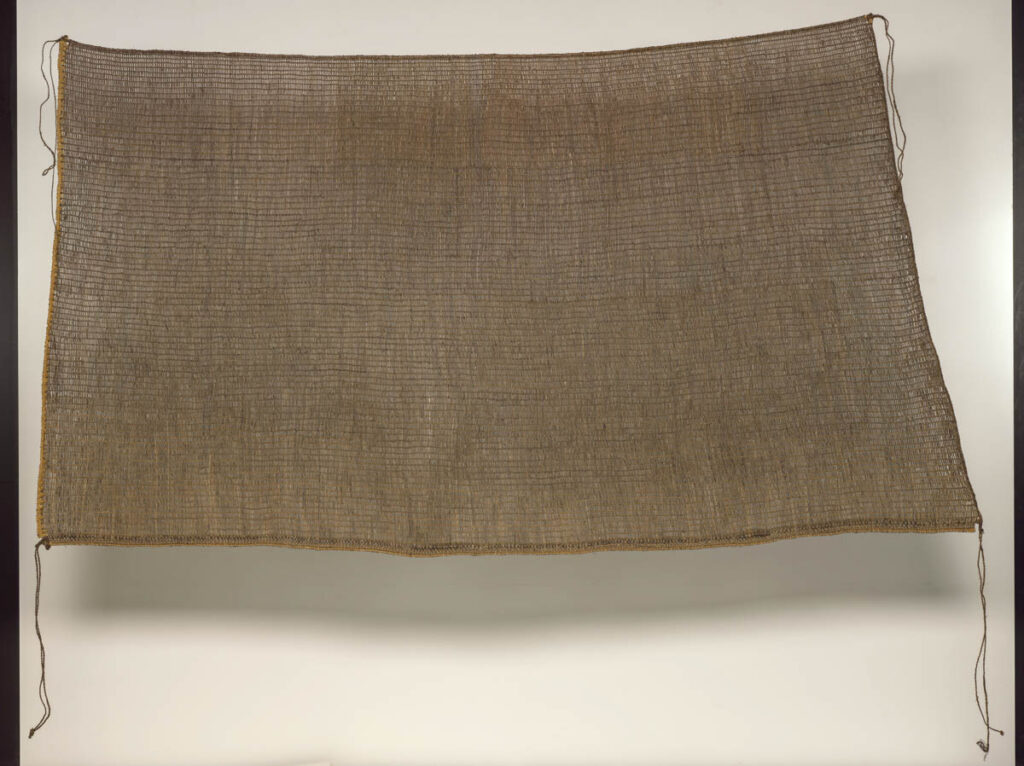

Margaret Rarru – Dhumala sail

Margaret RARRU, Liyagawumirr people, Australia b.1940, Dhomala (Macassan canoe sail) 2019-20, Woven pandanus (Pandanus spiralis), Hand-rolled kurrajong (Brachychiton populineus) bark string, 150 x 281cm, Commissioned 2019 with funds from the Queensland Art Gallery l, Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection Queensland Art Gallery l Gallery of Modern Art

Margaret Rarru is a master weaver and recognised as the leader of a strong family group known for their cultural and innovative artistic practices. She lives and works with her family between the islands of Yurrwi (Milingimbi) and Langarra off the northern coast of eastern Arnhem Land. Rarru has exhibited extensively in Australia and internationally.

Early in life Margaret Rarru learnt the techniques of twining pandanus and spinning string to make traditional everyday and ceremonial objects. Not content with just following tradition, in the 1980s she began working in the introduced coil-weaving technique to create innovative sculptural forms, including the “Madonna bra” inspired by videos she’d seen of the pop star. Rarru was the first in her region to discover the still rare mul (black dye), achieved in a secret process mixing leaves and other natural substances, with which she colours pandanus leaves and bark string. Today, Rarru is known for her black-dyed bathi mul (large-scale coil-woven baskets) and mindirr, closely-twined conical baskets.

Margaret Rarru and her sisters grew up learning the deeper meanings of fibre objects. They were also taught their minimalist clan body designs and the techniques for painting them on bark and wooden memorial poles. They were also keenly aware of the contact between Makassan fishers/traders and Yolŋu, evident in the circle of stately tamarind trees surrounding a local Milingimbi (Yurrwi) water-hole, and preserved in ceremonial songs, dances and symbols.

In Dhumala (Makassan canoe sail) Rarru has used a coarser twining stitch, to form the mat-like sail, based on the design that developed parallel with the lipalipa (dug-out canoe) being introduced by Makassans to northern Arnhem Land shores. Lipalipa were carved from the relatively soft wood of bombax trees, with metal tools brought by Makassans as items of trade with Yolŋu. Makassans also taught them the techniques they used for crafting their large wooden sea-going perahus. Lipalipa could navigate the open seas under sail, greatly enhancing Yolŋu communication and marine hunting, whereas previously, with only stringybark canoes (derrka), movement was restricted to freshwater travel and crossing estuaries.

Rarru’s dhumala is of a useable form and scale and prepared for rigging using hand-rolled rope made from the inner bark of a kurrajong tree. However, she exploits the subtle colour gradation of the near metallic black strands to emphasise the elegant contours and surface patterns created through the process of hand-weaving, to create a bold yet restrained work of design.

Gunybi Gunumbarr – Djirrit sail

Gunybi GANABARR, Ngaymil people, NT b.1973, Djirrit 2021, etched Aluminium composite board, 248 x 150cm, Buku Larrnggay Mulka Centre

In early December 2020, Gunybi and Yinimala Gumana set off with family to go turtle hunting. They drove from their homeland at Gäṉgän a few hours down the bush track to Garrapara (Grindall Bay). From there they launched to the bätpa (reefs) around Woodah Isle. Their engine broke down near Woodah Isle whilst turtle hunting so they paddled to the shore of the island where they were able to find food, fire, shelter and water. The party then set about fashioning a sail from what they had available in order to find their way home.

“We took copper wire off the spears to use to thread the shirt and the canopy together and attach it to the harpoons which had been tied together.”

Gunybi and his son Daniel worked with Yinimala Gumana, his djuŋgaya (spiritual manager), Mangila Munuŋgurr and Buluŋgitj Marawili to sew the boat canopy and their shirts into a Makassan sail which could be deployed from their turtle harpoons. The next morning once tide and wind were favourable they set sail for home where they were intercepted by the Police Boat which had been launched after travelling from Gapuwiyak due to reports that the men had been missing overnight.

The sail was purchased for inclusion in the 10th Asia Pacific Triennial. A photograph taken by the Police crew was posted to the NT Police instagram. Gunybi went on to create a large engraved Alupanel rendition of the photograph.

This is Gunybi’s account;

“Djirriṯ is the name we call this sail with the diagonal mast. It was the late Dry season. The start of the Wet before the first rains start. This is the right time to hunt turtle and when the maypal shellfish, the mekawu- rock oysters are at their best. We intended to get Mulkurrmi, use an axe to chop large sections of oysters off the rocks to bring home. We drove the boat down to Garrapara where we launched and went straight out to Gunyuru (round Hat Island). We cruised around for a while but didn’t find any miyapunu (turtle). So we went straight out to Woodah Island and immediately got two big Dhalwaṯpu (Green Turtle).

It’s a crazy thing but by this time I was starving for ŋarali (cigarette) and only had rolling tobacco and no papers. I hadn’t brought my luŋiny (pipe). So I took us into shore at Woodah Isle where I saw a Luŋiny tree so I could cut myself a pipe. We landed and I cut a pipe hollowed out the stem added a bullet shell as the bowl and had a smoke. When we went back to the boat and hopped in to take off again we found the battery was flat. We couldn’t start the boat! I tried pushing the starter repeatedly but there was no spark.

By this time it was late afternoon. We had no firewood so I went up the hill and got some wuḏuku (driftwood) from the beach. We had three jerry cans of water and we had all the oysters we could eat. We had a quiet night though we had no light other than the moon and the fire we were joking and laughing and relaxed because we knew we could sail in the morning using the djambatj (harpoons). I had already seen the boat canopy and the ropes and knew that we could do it.

In the morning Yinimala and I got the guys together and explained what we needed to do. We took copper wire off the spears to use to thread the shirt and the canopy together and attach it to the harpoons which had been tied together. When I woke that morning I saw the waŋupini (thunderhead cloud) on the horizon and I said to Yinimala, “Look that’s the wind waiting for us!”

We were waiting a long time for the tide to come in so we used wood to roll the boat out a long way to meet the water. Then we let one of the turtles overboard with a rope attached and she towed us out into the deep water. As we reached the edge of the reef I cut the rope and let her go and the wind caught us.”

Broken pots in the sand

WUNUNGMURRA, Nawurapu, Dhalwangu people, Australia NT 1952‑2018, Macassan pot 2016, Ceramic, 11 x 10cm

Three houses on a white-sand beach, in a palm-fringed cove, inside a pristine harbour. Sparkling blue water. Only one other small homeland is visible across the bay. Massive granite rocks like statues stand out of the water and line the shore. This is Bawaka—home of the Burarrwanga arm of the Gumatj clan. Their ownership is embedded in the epic song cycles which encode the intimate knowledge of place. But that hidden history is also ours.

Because within those songs is material that is intrinsic to the history of the whole continent and everyone on it. Snatches of Islamic and Bugis influence have been preserved through meticulous cultural discipline. There are verses that landowner Djawa Burarrwanga sings that he does not know the full meaning of. Some are excerpts of the Bugis creation myths which have been suppressed and lost in their place of origin. There are also audible references to Allah and Mohammed sung within traditional Yolŋu manikay (sacred song). Intimates of Bawaka recognise its Bugis name—Gambu Djiki. At least that is the Yolŋu alias. A rendering of Kampong Zikir (Heavenly Village).

Imagine being able to go to a beach where you are certain to collect a handful of centuries-old pottery shards in half an hour. Where you can scan the brilliant white sand looking for worked earthenware, sometimes marked with its maker’s fingerprints, and once collected and appreciated, return it to nature. This has been my joy for 20 years at Bawaka.

As the years passed, I started to wonder “How can there be so many shards here?” It is an extreme climate. The fragile ceramics have laid here through scorching sun and cyclones for more than 100—perhaps 500—years. Yet there is literally an inexhaustible supply of ancient pottery here. Allowing for hundreds of years of exchange, involving thousands of vessels, still couldn’t explain how these fragments were surfacing in such volume.

Nawurapu and Jamie Wunungmurra and I went to Sulawesi. I will never forget the afternoon when we met Abdi Karya at the famous Rumata Art Space in Macassar city. I told him of my quest to understand this conundrum and showed him a picture of the fragments on my phone. “Have you any idea where these pots could have come from?” He laughed with his twinkling eyes and pointed to the ceramic pots lining the courtyard, and said:

Here they are! Haha! They are made by the Torajan people of the village of Soreang in the Takalar regency nearby. They are rice and corn farmers who excavate paddy terraces from the clay on the hillsides. They form these pots and when the harvest is over they fire the vessels with the discarded husks. In the historic times, they would trade these with the seafaring Bugis and Bajau sailors who would use them to carry their trade goods as they plied their trade from island to island.

But I was still confused, even though I now knew where the pots came from. I knew that they hung from the decks on the trading pinisi or perahu sailing vessels of the Bugis traders. I knew that Yolŋu and Makassans worked side by side to harvest the darripa (trepang sea cucumbers). And from the very formal, respectful greeting the Bugis employed when addressing their hosts the landowners, I knew that Yolŋu called outsiders Ŋapaki.

But I still could not fathom the amount of material in the sands of the Heavenly Village. Eventually, I turned to Djawa and again asked the simple question I was trying to solve. Again he laughed, saying:

You already know the answer to this. You know the songs, don’t you? The songs of Bawaka!? Its right there—Buthuḻu baḏaw! Buthuḻu baḏaw! The songs tell us why there are so many rupa (pots) here. The songs tell us of the harvest working together side by side, sharing and trading. And at the end, a great party. Our friends bring out all of their fine goods. We laugh into the night. We celebrate our hard work. We sing and dance. And then when it is finished and we have drunk all the nanitji and eaten all the fine food, we smash the bottles and they burst and explode! Surely you knew that?

The associations Yolŋu had with the seafaring Makassans are recorded in the ancient songlines of the Dhalwaŋgu, Gumatj, Munyuku and Rirratjingu clans.

Some of these songs tell of the first rising clouds on the horizons—the first sightings for the year of the Makassan perahus’ sails, which appear like these clouds. They lament the setting of the sun, which correlates to the passing of a loved one. The red sails in the sunset are part of Djapana (Yothu Yindi’s famous sunset dreaming song) which means sunset in Yolŋu matha, and farewell in Bugis. The grief of returning sailors, who raised their masts and departed to Sulawesi with Bulungu (the south-easterly winds of the early Dry season) is incorporated in Yolŋu mortuary ceremony. But as the sun also rises, so the return of the Makassans with Lunggurrma (the Northerly Monsoon winds of the approaching Wet) is an analogue of the rebirth of the spirit following the appropriate rituals.

In, and through, this exhibition the sun rises again, and the spirit of our ancestral connections is renewed. The pots are on the move once more.

About Will Stubbs

Will Stubbs worked as a criminal defence advocate in Sydney and the Top End for ten years. In 1995 he married Yolŋu scholar Merrkiyawuy Ganambarr and began working at the Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka Centre. He has worked there ever since. In 2015 he was awarded the Australia Council Visual Arts Award for Advocacy. Visit Buku-Larrnggay Mulka, follow @bukuartnow and like Bukuart.

✿

Yolŋu – Makassan project was part of the 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art

Co-curators: Abdi Karya and Diane Moon

Artists: John Bulunbulun, Ganalbingu people (1946-2010), Australia; Nalkuma Burarrwanga, Gumatji, born 1973, Australia; DIE2TIE Studio, Indonesia; Gunybi Ganambarr, Ngaymil people, born 1973, Australia; Merrkiyawuy Ganambarr, Datiwuy people, born 1959, Australia; Abdi Karya, born 1982, Indonesia; Dr B Marika Ao, Rirratjingu people, born 1954, Australia; Dhuwarrwarr Marika, Rirratjingu people, born c.1945, Australia; Barayuwa Munuŋgurr, Djapu people, born 1980, Australia; Djakapurra Munyarryun, Wangurri people, born 1973, Australia; Margaret Rarru, Liyagawumirr people, born 1940, Australia; West Sulawesi Artisans, Indonesia; Ms M Wirrpanda, Dhudi-Djapi people, 1947–2021, Australia; Djirrirra Wunungmurra, Dhalwangu-Narrkala people, born 1968, Australia; Nawurapu Wunungmurra, Dhalwangu people, Australia 1952–201