Alisa Tietboehl writes about a Japanese weaving mill that sustains its local craft through skill and innovation.

A small town near Nagoya, Japan called Ichinomiya is known for its high-quality wool and manufacturers. A family-led weaving mill since 1949, Kondo Weaving Mill has been focusing on natural fibres, particularly linen and wool and specialises in fabrics that combine the textures of each fibre. Currently led by a husband and wife team, the husband’s grandfather founded Kondo Weaving Mill.

The textile industry of Japan is facing major challenges due to the aging of crafts(wo)men and the younger generations not interested in learning the craft. Kondo Weaving Mill took it upon this challenge to lead by example and hires trainees every year, believing in the future of the textile industry of Japan. Since Kondo Weaving Mill is a small family-led mill, they have been focusing on creating textiles for apparel only. However, they are currently also working to make textiles for interior, home fabrics and collaborating with artists. Currently, Kondo Weaving Mill is collaborating with an artist on In-Fuse 02 using Japanese Mino Washi threads.

Mino washi is a type of Japanese paper made in Gifu prefecture. Washi is made from paper mulberry which is a plant that grows in the naturally rich environment city of Mino with its clear water from nearby rivers and the support of local people to preserve the tradition of Japanese Mino. Traditionally the paper was used for shoji sliding paper doors in the temples or shrines of Kyoto, and for local crafting industries like paper fans, paper umbrellas, and most paper lanterns. Hon Minoshi is the highest quality of paper and its production methods were designated as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2014, only three washi styles in Japan have received the honour.

Kondo Weaving Mill creates textiles with sensitivity and skill. Mixed textured linen, wool and cotton make for a robust, but soft-touch fabric. The draped feel of linen, silk and cotton is gentle, yet sturdy. Ichinomiya is located in Aichi Prefecture and is surrounded by many different textile factories, each specialising in a different craft. Kondo Weaving Mill collaborates with a leftover dye factory in nearby Gifu or a local craftsman who dyes textiles using persimmon dye, known as kakishibu.

Let’s take a closer look at some of the fabrics woven by Kondo Weaving Mill.

Wool/Linen

The beautiful subtle reddish-black color is created by three different tones of black. These tones of black are woven into the fabric and create a nice depth in color. Very high-density weaving with slub yarns. The color is inspired by a Japanese vintage iron teapot. The aim is to create beauty in aging.

Black Land Hemp

Black Land Hemp comes from the fact that the hemp plant is grown in very dark soil, hence the color name. Two different types of original yarns are specifically twisted together and woven with high density. In combination with a special finishing. A great balance between solid and soft, clean yet rustic.

Cotton / Kasuri Yarn

Kasuri dye is a way to dye yarn in multiple colours to achieve a special surface on the fabric. It is a form of ikat dyeing, traditionally resulting in patterns characterised by their blurred or brushed appearance. Kasuri yarns are woven into the fabric to make uneven stripes. The aim is to create the virtues of imperfection, known as “wabi sabi”.

Wool/Cotton

This fabric looks denim but technically it is not denim. There is a surprising texture and feel as well as lightness to the fabric. Five different yarn-dyed colours make the fabric colour so rich and special. The subtle greenish-blue colour is inspired by the genuine indigo colour (called aizome in Japanese) which you can only see in the process of dyeing, before oxidation.

The yarn is put into water to be wet so that the yarn can absorb the dye easily. The yarn is then dyed as a modern version of kasuri dye. After the yarn is dyed, the yarn is put into a steaming machine to set the colour. Without steaming, the colour will gradually fade.

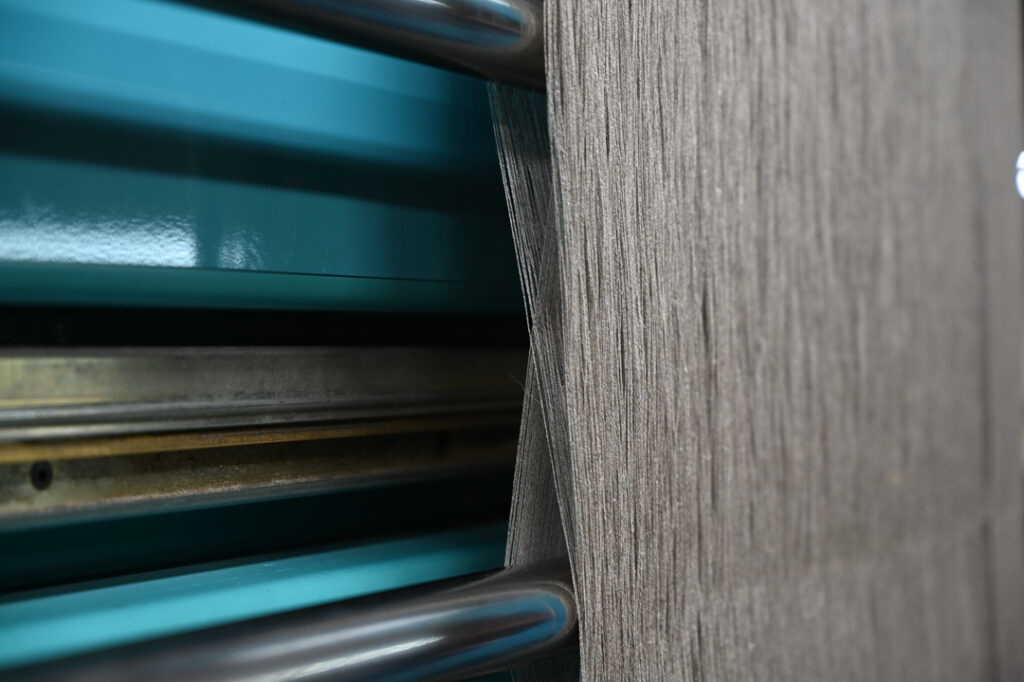

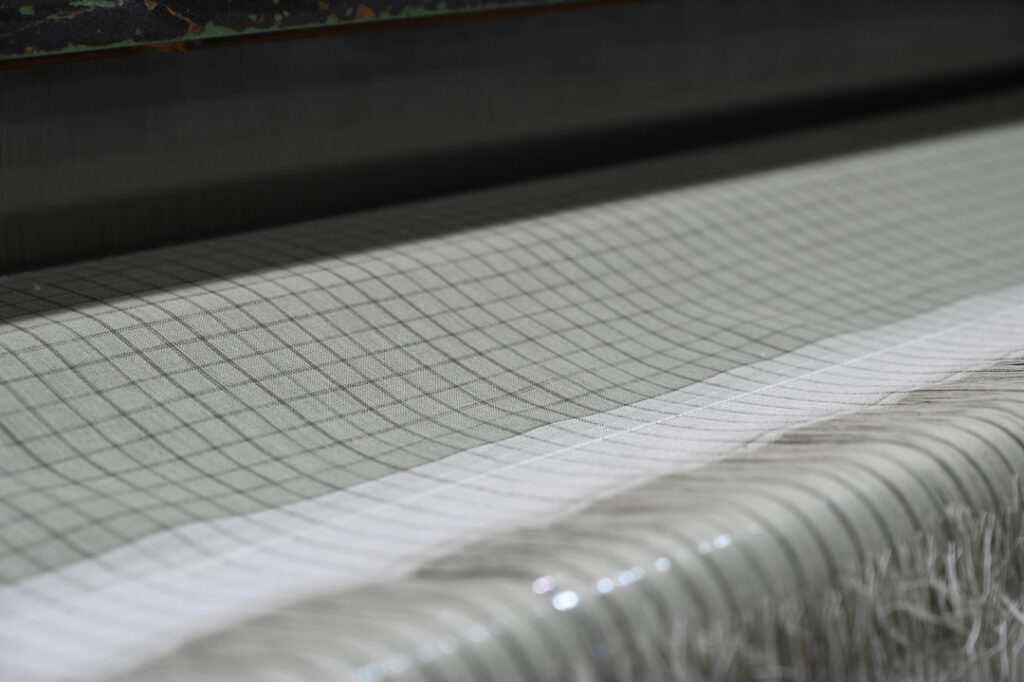

When the yarn is fully dried, it goes into a hank reeling mill to be made into yarn cones to prepare for the weaving process. Since each yarn cone is big, they need to be divided into smaller yarn cones for warping. Warp is the grain line (lengthwise yarns) of the fabric. Warping is the process of combining yarns from different cones together to form a sheet. The important point in the warping is to preserve the yarn elongation and maintain it. Once the weaving process is done, the fabric is sent to a finishing mill. The fabric before the finishing process is called greige.

Kondo Weaving Mill’s vision for the future is to make the textile industry appealing to the younger generation and continue to use natural fibres. With sensitivity and skill, Kondo Weaving Mill will continue to work on textiles with enthusiasm.

Arimatsu Narumi Shibori

A new way of understanding WA

WA is a unique Japanese concept, which usually is translated as harmony in English.

Arimatsu, a town near Nagoya, in Central Japan is famous for the historic tie dye technique which has produced colourful fabrics for over 400 years. Only a few manufacturers are left in Japan that develop the Arimatsu Narumi Shibori technique.

What is Shibori? Shibori is a dyeing technique expressed by tightly tying the fabric with yarn, and the entire process is manual. The shape of each point is different depending on the hand. Since it is expressed by precise manual work, there are no two ways to get the same pattern.

The roots of Arimatsu-shibori and Narumi-shibori date back to the early Edo period (1603-1867). The technique of shibori itself began in the Nara period (710 to 794). The history of Arimatsu-shibori and Narumi-shibori began when Takeda Shokuro, the founder of Arimatsu saw the tie-dyed kimonos and made hand towels to add value using tie-dyed Mikawa cotton, famous for its cotton production. The roots of Arimatsu Narumi shibori are said to have been the sale of hand towels and yukata (summer kimono) as souvenirs for travellers. In 1975 Arimatsu/Narumi was designated as a traditional craft by the Minister of Trade and Industry (currently the Economy, Trade and Industry). A characteristic of Arimatsu-Narumi shibori is the large number of techniques. There are more than 100 types of shibori techniques. A wide variety of techniques and hand-sewn skills create a wide variety of designs. One of the charms is that even with the same pattern, the pattern can be subtly different depending on the strength of the crafts(wo)men.

Among the many shibori techniques, we’ll take a closer look at Itajime, kagozome and a unique fabric, containing three different shibori techniques.

Itajime is a technique that is dyed using two wooden boards for the fabric that is covered, to remain undyed. Shapes such as triangles and squares are common using Itajime. Itajime is probably the most known shibori technique.

Kagozome is not a very common shibori technique. “Kago” in Japanese means “basket”. Originally baskets were used for this technique. The dye house shown in the images developed its own kagozome technique. The fabric is put on a metal mesh and wrinkled with hands. After the wrinkling process is done, the dye (image shows bleach) is poured all over leaving sprinkles of dye creating a beautiful dynamic pattern.

The square fabric is a special fabric using three different tying techniques with three different dyeing colours. The white fabric is a blend of cotton and linen. Starting with the darkest base colour, the fabric is tied in two different ways. One way is tied to create a pattern, and the other way is to cover it completely so it remains undyed. The part that is tied to create a pattern is then untied and dyed a second time. The third and last time is dyed, uncovering the completely covered parts (white squares) and dyed. After air drying the fabric, usually it is steamed so the pattern shows beautifully.

The philosophy of Arimatsu Narumi shibori is to protect the traditional craft and leave its techniques within the local area of Arimatsu, Aichi.

About Alisa Ota Tietboehl

I was born in Bonn, Germany to a Japanese mother and German father. I grew up in Bangladesh, Spain, Japan and Germany. Currently, I live in Tokyo, Japan. My own multicultural background and interests in other cultures, together with a knowledge of several languages, have left me passionate about textiles, craftsmanship and traditions in art and culture. I am a graphic and communication designer currently navigating different projects in apparel, textile, trend research and as a guest writer for www.trendland.com. Currently, I work together with my husband on our brands MAOTA and naensis, which are both an ode to Japanese craftsmanship, sustainability and a passion to keep traditions alive. Visit www.alisa-alisa.com (personal website) and www.naensis.com (coming soon)

I was born in Bonn, Germany to a Japanese mother and German father. I grew up in Bangladesh, Spain, Japan and Germany. Currently, I live in Tokyo, Japan. My own multicultural background and interests in other cultures, together with a knowledge of several languages, have left me passionate about textiles, craftsmanship and traditions in art and culture. I am a graphic and communication designer currently navigating different projects in apparel, textile, trend research and as a guest writer for www.trendland.com. Currently, I work together with my husband on our brands MAOTA and naensis, which are both an ode to Japanese craftsmanship, sustainability and a passion to keep traditions alive. Visit www.alisa-alisa.com (personal website) and www.naensis.com (coming soon)