- photo: Trent Jansen

- photo: Trent Jansen

- photo: Trent Jansen

Porosity – Kabari was a project involving Australian object designer Trent Jansen, architect/sculptor Richard Goodwin, Indian graphic/object designer Ishan Khosla and students from ISDI Parsons Mumbai. The project involves designers collaborating in Mumbai’s “Chor Bazaar” (thieves market) and Studio X, using the bazaar as their only source of materials and making processes.

This project challenged Western principles of design that focus on a controlled practice where materials and processes are clearly defined in advance. Below is a selection from the notes of Trent Jansen describing how he approached working with a potter in Mumbai’s Dharavi, the populous informal settlement made famous by the film Slumdog Millionaire.

Jugaad

I am interested in the Australian philosophy of make do—to do your best with what you have. Jugaad is the Indian make do, with a slight twist. Jugaad is doing the best you can with what you have, but it is also figuring it out as you go—improvising, rather than planning the direction forward. You can see this philosophy in action everywhere in India: from the way that people cross the street—stepping off the footpath and meandering through the traffic in which ever direction provides a free path; to high-rise construction—steel reinforcement protrudes from half built sky-scrapers all over this country. It seems that these projects will be finished when there is the time and/or money to do so.

First week

The first week of Porosity Kabari has come to an end, and what a chaotic week it was. Each designer working on Porosity Kabari is developing projects based on their own observations and interests, but there does seem to be one core thread tying these disparate works together—jugaad.

For me, the Chor Bazaar and Porosity Kabari are all about jugaad, and this makes me a little nervous. I am used to researching projects thoroughly and working through production processes in a very controlled manner, but with the Porosity Kabari Exhibition opening in Mumbai in two weeks, who has time for planning or control? Everyday we head into the bazaar and observe the makers who work in this hub of industry. We observe and then we react, generating ideas by improvising forms based on those that are possible, using the techniques and/or materials that we see. We also improvise our way through the making process, as options, problems or questions arise, we suggest the best immediate solution that comes to mind.

I am beginning to think that the objects produced in this way for Porosity Kabari will be of little significance in and of themselves. There are so many materials, processes and possible design directions to explore here that the artefacts we make will be a small sample of what might have been. These objects are not carefully thought out, meticulously planned or painstakingly crafted, they are not the self conscious innovations of designers presenting their most treasured ideas to a critical audience. The outcomes that we reach are completely dependant on the alley way we chose to venture down, and the material or maker that just happened to be at the end of that street. The outcomes of Porosity Kabari are equally dependant on our state of mind at the moment that we noticed (or didn’t notice) a potentially interesting material or process, and our momentary train of thought in the instant that we attempted to design that material or process into an object of interest. The short period of time allocated to this project, and the immediacy with which things are made in the bazaar, mean that we do not have time to sit and ponder on the most innovative or beautiful design direction. The decision must be made now.

Each object is an experiment with jugaad, with every improvised decision sending that project in a new direction. With the destiny of each object guided by a series of instantaneous and unplanned decisions, who knows where they will end up. What ever the outcomes, they will be the physical embodiment of jugaad—figured out as we go.

Dharavi

We went to Dharavi, the largest slum on the face of the planet, to visit a potter by the name of Abbas Galwani. I have seen some throwing in my time, but I have never seen throwing with the speed and accuracy that Abbas demonstrates. He is a truly skilled potter, working in a society that holds little regard for traditional crafts such as his.

The potters working in Dharavi throw utilitarian objects, such as saucers for chutney and bowls for kulfi. These are not aspiration objects, but disposable, one-use vessels, and the price that they command on the domestic market is very low. According to Abbas, the average potter family working in Dharavi will make roughly 4000 small vessels in a day, and they will sell these 4000 vessels for roughly $10. A full day’s work for $10. Abbas is a skillful thrower, and although he is skilled in other areas of ceramic construction, I wanted to explore the traditional thrown terracotta that has been used to produce chai cups and lassi vessels for centuries.

In Abbas’ studio I sketched out some designs for a collection of terracotta furniture that fuses a series of typical thrown forms, to create functional furniture objects. By connecting a large, open bowl with four elongated vessels, we achieve some forms that might function well as seats and tables. We have been told to come back tomorrow afternoon to see the components of our first stool. So long as you’re not talking about the traffic, things can move very quickly in India.

I find myself traveling to Abbas’ studio in Dharavi most days to oversee the next phase of making, so to ensure that the work is done exactly to my specifications. This is not improvisation—this is the most anal retentive planning I can think of. Despite the fact that we have improvised our way through the formal development, and are improvising solutions to problems as they arise, I am still trying to control the outcome.

- photo: Trent Jansen

- photo: Trent Jansen

- photo: Trent Jansen

- photo: Trent Jansen

- photo: Trent Jansen

- photo: Amy Luschwitz

Deadlines

This week the gods of jugaad stepped in and took this control out of my hands. All week I have been trying to spend time with Abbas, to oversee the throwing of the forms that we require, and the connection of those forms to make the final objects. Our deadline for this project is looming, and Abbas has told us that he needs to begin the firing process on Sunday 14th February, otherwise the work will not be ready until after the opening of the Porosity Kabari Exhibition—not ideal. Abbas is one of the hardest working people that I have ever met, and this week his work ethic caught up with him in the form of a mild illness. Earlier in the week we had arranged to meet Abbas in his studio at 7:30am to make some headway on the project, and at 6:30am I received a phone call from a sleepy Tausif, saying that Abbas had a fever and could not work that morning. Abbas had asked us to come in the afternoon instead. Of course the afternoon came and Abbas was still not feeling well, so there was no potting that day. A day is a very long time in a three week project.

On Friday I arrived in Dharavi at 7:30am to work with Abbas, but he was still unwell, and needed a couple of hours sleep before we could begin, asking us to return at 11:30. I traveled back into Mumbai and called Abbas at 10am to make sure that our 11:30 appointment was still possible. Over the next couple of hours our window of time to work with Abbas reduced from 8 hours to 1 hour—I was due to fly to Jaipur that evening, and with Mumbai traffic it was essential that I leave the studio by 4pm to make the flight. So, I had one hour to observe some assembly and do my best to communicate the precise detailing that I required, before running out of Dharavi to catch a taxi to the airport.

This afternoon Abbas will be giving shape to these terracotta objects without my guidance. That is very difficult for me to come to terms with, but India and jugaad intervened with my controlling design approach in a way that I could not avoid. Of course I closely considered missing my flight and not going to Jaipur for the weekend, but at the last minute I caught myself being controlling of a process that was not intended to be controlled, and convinced myself to go. Perhaps it was the deafening wedding party brass band practicing outside Abbas’ studio (too loud to hear myself think) that clouded my judgment. Or was it Narada, the Hindu god of mischief, that forced me to leave Dharavi? Either way jugaad has prevailed and I nervously await the results.

This week has been a challenging week for improvising with pottery, but we have managed to forge ahead in some areas, toward an impending firing deadline.

Despite some major delays we managed to work with Abbas Galwani over two days this week, preparing the potted forms for assembly, and eventually assembling some of the objects. In communicating the exact way in which the designs were to be assembled, we used every communication method in the book, from technical drawings to 3d models, and rusty calipers to marks made in the surface of clay. In the end I think that the message was clear, however I can’t help but worry about the inevitable miscommunication that comes with working across a language barrier.

- Trent Jansen and Abbas, Jugaad with pottery

- photo: Neville Sukhia

The results

Abbas is assembling the remaining forms tonight, while I am in Jaipur, so that they can go into the kiln tomorrow.

Earlier in the week Tara and I were asking Abbas a little more about the history of his family, as he was cleaning up some of our terracotta forms. Abbas says that his family have been potters as far back as he is aware, his great-grandfather making terracotta roof tiles and chimneys in Kutch. After Abbas’ grandfather died during a terrible drought in Kutch, Abbas’ grandmother was forced to move the family to Mumbai so that she could provide for her children. Dharavi became a new home for generations of Galwanis.

When I first returned from Jaipur to see the finishing touches that Abbas had made, I was disappointed. The final cut that is made to allow an opening for sitting was not in the exact position, or on the angle that I had specified. However, by the time the work was fired I had allowed the jugaad spirit to take over a little more, and had begun to appreciate the idiosyncratic nature of these final touches made by Abbas.

Now when I look at the stool I love these details. They are unrefined, and ill-considered, but jugaad and the imperfections that result from it are the true innovations of this project… Without them we were three designers trying to make products in India. Jugaad has transformed these objects from soulless objects into physical embodiments of a living culture.

Postscript: Dropping a Kumbhar Wala matka

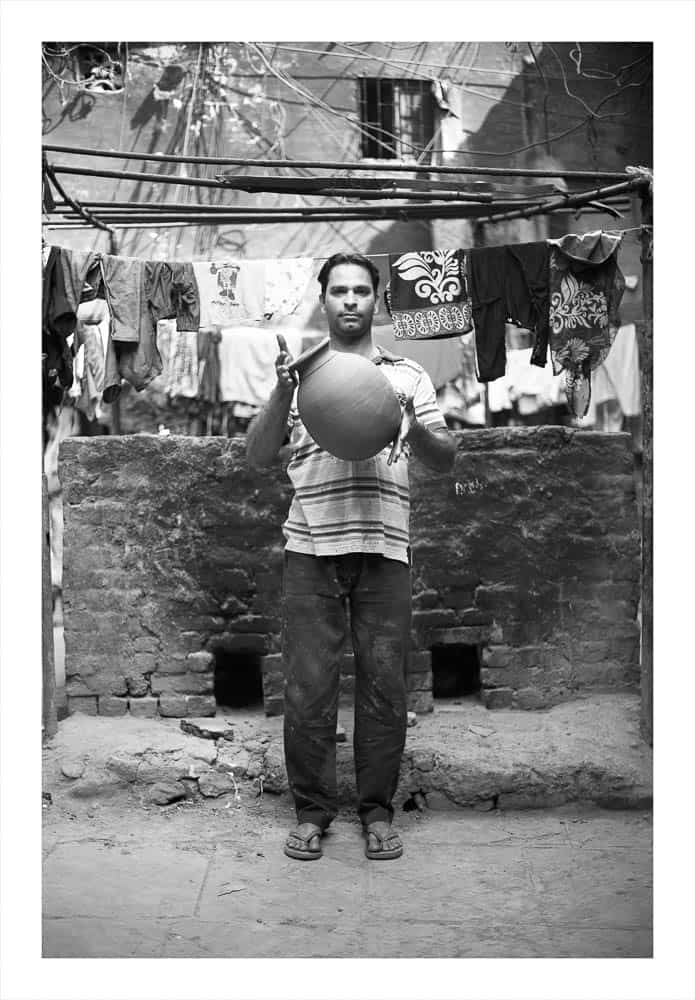

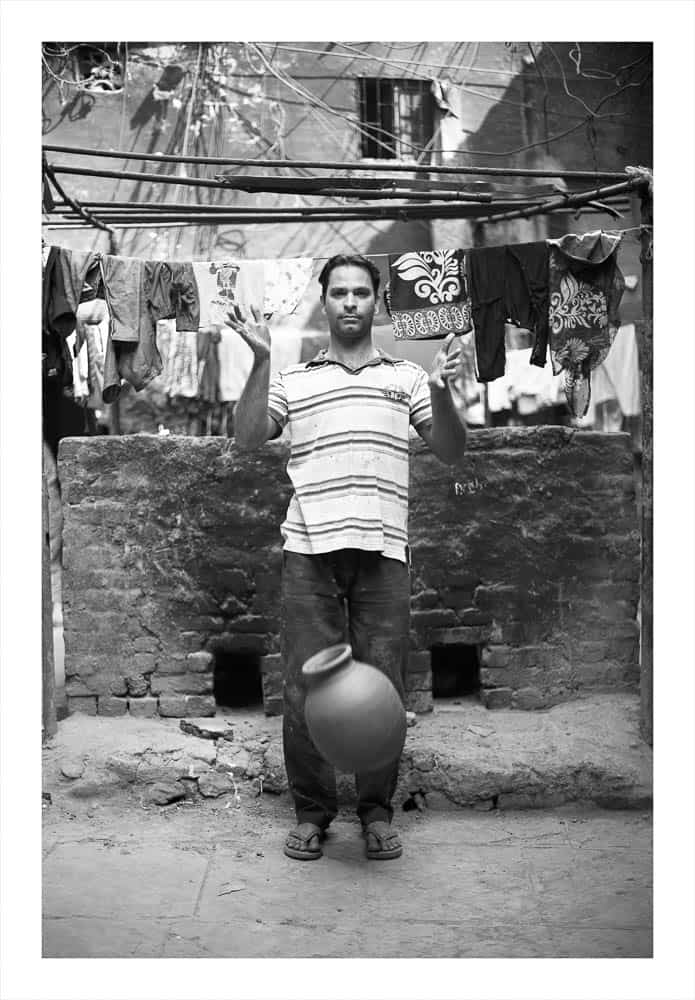

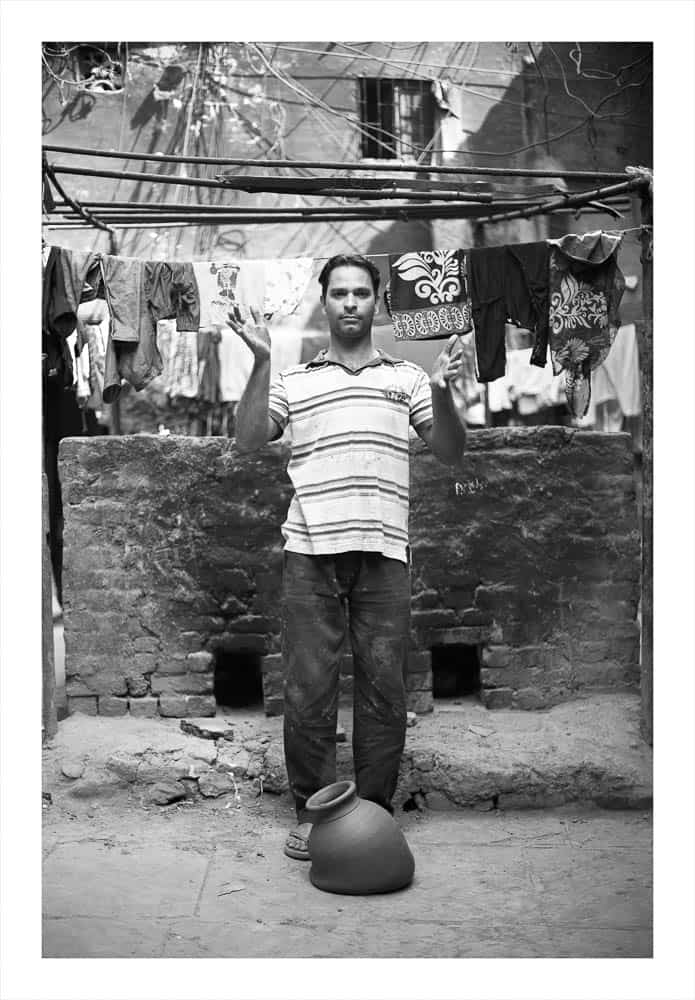

- Abbas Galwani

- Abbas Galwani

- Abbas Galwani

This work pays homage to Ai WeiWei’s controversial and innovative work, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995. By destroying an object that embodies two thousand years of Chinese tradition, culture and history, WeiWei openly denounces the conventions that are used to legitimise centuries of indoctrination and malevolent actions, perpetrated by the Chinese establishment.

Dropping a Kumbhar Wala Matka offers a similar critique of the traditions and history that underpin Indian social conventions. In India, the Kumbhar Wala (potter) is among the lower castes, meaning that these craftspeople, who make functional objects serving millions of Indians on a daily basis, do not earn the respect that they deserve for their role within Indian society. Kumbhar Walas work extremely long hours, making thousands of thrown objects every day, and the remuneration received for their many hours of toil is nowhere near that of higher, more traditionally educated castes. The Kumbhar Walas working in India are some of the most skillful clay throwers in the world, but they are not recognised for their skill and they do not receive the reverence that they deserve.

In this work, Abbas Galwani, a Kumbhar Wala living and working in Dharavi, drops a traditional Indian Matka. With this act, Abbas denounces the cultural structures that restrict his social mobility, impede his ability to gain renown for his unquestionable skill, and hinder his capacity to provide for his family.

I have always embraced the conceptual system of Post-Modern design, but after two weeks of improvising in the bazaar, I am beginning to wonder about the degree of innovation that can result from any process that follows a core set of rules. Perhaps the lawless nature of the bazaar can open up designers to possibilities that cannot come from a university sanctioned design scheme.

Author

Trent Jansen is a designer based in Thirroul, Australia. Trent holds a Bachelor of Design from the College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales in Sydney, spending a portion of his degree in the Department of Art and Design at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada. At the moment Trent teaches as part of the Integrated Product Design Department at the University of Technology, Sydney and the School of Creative Arts at the University of Wollongong. Trent Jansen is represented by Broached Commissions and Living Edge in Australia, and Gallery All in Beijing and Los Angeles. His website is www.trentjansen.com.

Trent Jansen is a designer based in Thirroul, Australia. Trent holds a Bachelor of Design from the College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales in Sydney, spending a portion of his degree in the Department of Art and Design at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada. At the moment Trent teaches as part of the Integrated Product Design Department at the University of Technology, Sydney and the School of Creative Arts at the University of Wollongong. Trent Jansen is represented by Broached Commissions and Living Edge in Australia, and Gallery All in Beijing and Los Angeles. His website is www.trentjansen.com.

Comments

Hello,

Thank you, very interesting. Abbas Galwani sounds like a very skilled fellow. I’m wondering how you sourced him, how you went about negotiating his fee for making the stools (given that he usually makes $10 a day), whether this had to be done through an intermediary, and what it ended up amounting to? Also, how did he feel about the everyday terracotta then being reframed as high art? (Or high design?) Are you going to commission him or others to more of these stools/objects?

Thank you. Kath