detail: Heather B. Swann, Banksia Men, 2015, wood, metal, silk, glass, 230 x 75 x 75cm each (approx.). Courtesy the artist and Michael Bugelli Gallery, Melbourne

Heather B. Swann’s installation ‘The Night’ fits sweetly with the curatorial theme of the 2016 Adelaide Biennial, ‘Magic Object.’

This work evokes the dark mysteries of the Australian bush, as represented particularly by the genus Banksia, in the family of Proteaceae. The installation of nine Banksia Men at the Art Gallery of South Australia is in fact only one aspect of a more extended production, the performance work ‘Nervous,’ which will be premiered at the National Gallery of Australia in September 2016.

In addition to the larger work’s complex developmental narrative – of sculptural conception, artistic collaboration, literary and musical composition, theatrical performance and recording, there is also a rich backstory in the means of production. Knowing how and how much the making of this work has depended on Swann’s personal, manual labour adds to its conceptual, political depth.

There are two themes running through the Nervous work. The first theme is to do with eyes – closing the eyes to see inside, gathering the world through the eyes, and how the creative process might work. The second theme is a look at intense emotions and extreme states of being. I developed this list as I worked:

- magnificent obsession

- possession

- ecstatic vision

- melancholia

- schizophrenic night

- delirium

- passion

- anguish

- lament

- hysteria

- longing

- nervous

This second theme is linked to the first, in my mind, in this way. We experience extreme and intense emotions. For a society to work we must control these feelings, or at least hide them away. I think that it is these feelings, these intensities, these extremes that feed the creative process. If I close my eyes you cannot see what I am feeling. If I close my eyes I have a well of interior intensity. I swim in it. It comes out through my fingers.

- One of the drawings blown up big on the windows at NGA Contemporary in April/May/June 2015.

- I bought the black glass eyes from Germany. They were just lumps of glass on wire. Firstly I used a two part epoxy modelling clay to cover the wire stems. You can see the stems inside the eyelids so I did not want them to be just wire, also this makes the stems stronger.

When I started to make the work for Nervous I set myself the challenge of making sculptures that would exist as exactly that, sculpture. But also they would be able to work in a performance. There are eight sculptures in Nervous, one of which is the group of nine Banksia Men. The Banksia Men is the only sculpture from Nervous that is wearable. I did not conceive of the Banksia Men as ‘costumes’ as such. In my mind they have always been primarily and foremost, sculpture that could be performed with. I think that this is one of the reasons I decided to make so many of them, so that they would have strength in mass, in order to make an installation that will be sculpturally strong, more than a bunch of old coats, so that the work would have a presence, carrying the idea that these things can be inhabited and will be worn but that they also exist in their own right. They have their own force. They are a hybrid.

I bought the black glass eyes from Germany. They were just lumps of glass on wire. Firstly I used a two-part epoxy modelling clay to cover the wire stems. You can see the stems inside the eyelids, so I did not want them to be just wire. Also this makes the stems stronger.

Approximately 400 metres of silk – actually a good silk-cotton mix. Like a bombazine but with cotton not wool – a poor woman’s bombazine? I cut 315 strips of the silk at 80 cm wide. Then on each strip of silk there are about 53 to 55 straight lines sewn with a gathering thread. It is a beautiful thread from France that is polyester with a twisted cotton cover, so it is both strong and feels good.

That is approximately 16,695 lines of sewing. My mother Helen helped me with this.

Then each line of thread is ‘pulled’ so that the fabric gathers. I carried these strips with me everywhere, for months. I took them with me on trips to Melbourne, to Sydney, to Newcastle. I caught the train from Canberra to Melbourne in the middle of the winter because the tickets are a winter special and only cost fifty dollars each way. Each train trip, there and back, takes nine and a half hours. I did a lot of gathering of threads on this trip.

Having cut the fabric in order to gather it, I then sewed the strips back together, with the eyes slotted in as I went. I made the first few ‘coats’ completely by hand and then Helen encouraged me to try using the sewing machine. I have her 50-year-old Bernina. This was better, and saved my fingers.

At each end of the 16,695 lines of gathered thread there are three knots. So I have tied over 100,000 knots into this work.

Each ‘coat’ or ‘body’ has big soft pads in the shoulders and across the back as well as an interior pocket. The pocket serves these purposes: it bears the number of each ‘body,’ so as to match it to its armature and head; it holds a small bag of wood shavings and spices made by my friend Linda especially to keep away the moths; and it will be useful for the live performance, so that the Banksia Men can keep their mobile telephones close!

There are some 450 eyelids or sockets. Each one has three pieces of silk sewn together with an opening at the back. Inside this ‘pocket’ is an oval cut from leather for strength and shape. First, each side of the pocket is filled out with polyester stuffing. The stuffing is sewn in – I had to do this on a leather sewing machine. I made the first 50 eyelids on my Bernina but it was struggling. Luckily, not far from Canberra lives the carriage-maker and wheelwright Mark Burton. I was able to use his beautiful 1920s Singer leather sewing machine.

Next, I made a hole through the structure with an awl and then the covered-wire-stemmed glass eye was inserted into the middle of the eyelid socket pocket and the wire was twisted over at the end to hold the eye in tight. Then I folded the eyelid socket pocket in half and made some stitches in the sides to hold it in shape.

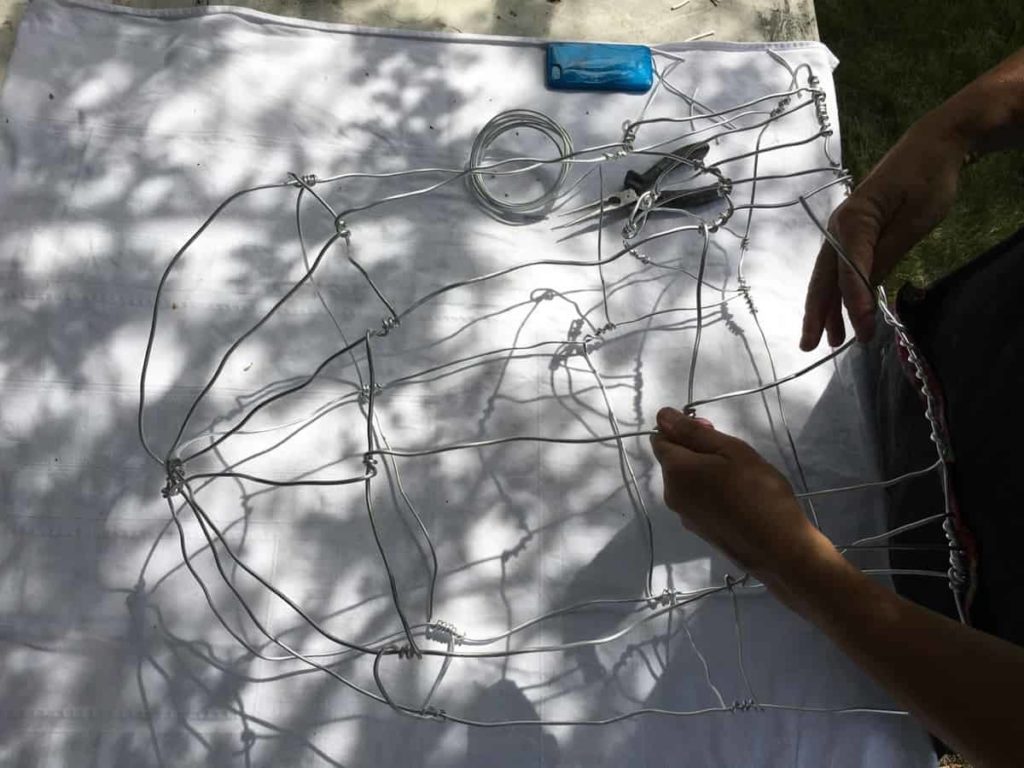

The head armatures are made of aluminium wire and black cotton-covered hat wire, which is a sprung wire. The aluminium wire is easy to manipulate but strong. The sprung hat wire holds its shape. I wrapped all the aluminium wire in cotton tape or black ribbon. This is an earlier armature and each connection is tied with cotton tape. As I went on, I discovered that I could twist the sprung hat wire on itself and so I did not have to make all these little ties. Each head is a different size although each shape is similar. There is a space left so that a performer can see out. This space is covered with a flap of the worked silk fabric while the Banksia Men are in their still state.

The body armatures I made with the help of my friend Mark. The metal base is steel rolled on a machine specifically designed for making wheel rims.

After making these metal wheels and having them powder-coated black I decided that they were too strong visually, too graphic, so I made nine wooden covers for them. I matched the timber to the floor of the exhibition space. After consultation with the artisan painters at AGSA, and having sent them a sample of the Sydney Blue Gum that I had especially sourced, we worked out a particular recipe of stain to use on my circular board panels, so that the tone would match that of the aged boards of the gallery floor.

At first Mark and I used sulky shafts for the spines of the armatures. Then we realised that these were too short and it was too expensive to use longer ones, so we went up to one of his many sheds and sorted through a whole lot of stuff until we found a great collection of handles, sourced from the stock of yet another Australian manufacturer discontinuing production: handles for hoes, rakes, and other agricultural tools. The spines are now all made of these handles, in rose gum and spotted gum.

The arms are cut from American poplar; they swivel at the shoulders to make it easy to put on the coats/bodies. The legs are all made of hickory, the spokes of wagon wheels. All the bolts we used are just plain blued steel, not zinc-coated.

The metal frames that hold out the body are all made of sprung wire again and soldered together. I wanted these armatures to be independent forms, nothing like a mannequin—and I think that I have succeeded. These scaffolds need to be able to stand naked and alone when their ‘coats’ and ‘heads’ are being worn during the performance.

Yards and yards of bombazine, 100,000 knots, black glass eyes, hat wire, rolled steel, spotted gum – these are the everything and the nothing of the work. Silky lumps of glass eyes balancing on thin wooden sticks. Lumps and sticks. The Night and its Banksia Men are seriously, even obsessively material, but in the end they are mostly made of melancholy, delirium, anguish and longing.

Author

Heather B. Swann is an Australian artist. She has been exhibiting her sculpture and drawings for over twenty years and is represented in a number of public collections including the National Gallery of Australia. For more information, see website iamnervous.net, which can be supported by the Australian Cultural Fund here. She is woodbu

Heather B. Swann is an Australian artist. She has been exhibiting her sculpture and drawings for over twenty years and is represented in a number of public collections including the National Gallery of Australia. For more information, see website iamnervous.net, which can be supported by the Australian Cultural Fund here. She is woodbu