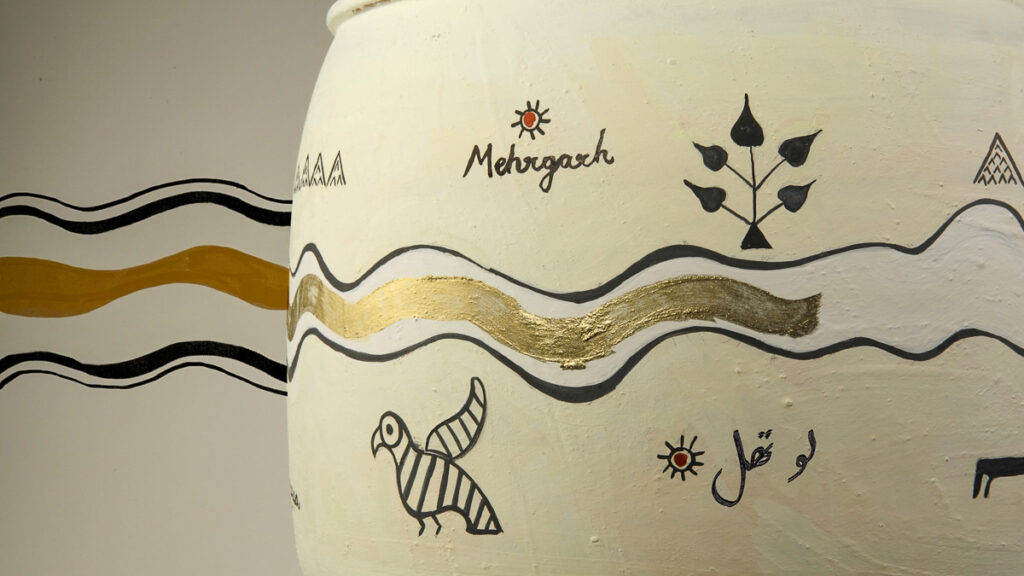

Pallavi Arora and Shirley Bhatnagar reanimate ancient pottery from the Indus valley civilisation

The story began with the curatorial brief put forward by Kristine Michael, where she asked us to collaborate on a project for the Serendipity Arts festival 2020. (This was in October of 2020 and due to the ongoing pandemic, this would be a virtual festival. We had three months to work on this as the festival went live on the 15th of December.)

Pallavi: The concept put forward by Kristine and Chandrika Grover Raleigh, in the brief was to explore the art of Kintsugi, and the concepts of creation and recreation. Kintsugi is the Japanese art form of mending broken pottery with liquid gold in order for the pottery to be made whole and usable again. The idea of not discarding that which is broken but instead rebuilding it and appreciating its new form with all its scars was something that resonated with me. For personal reasons I instinctively responded to the notion of broken fragments indicating a sense of loss and the process of recreating as a metaphor for healing.

Shirley: When the call for the collaborative project came, I had been collecting never-before-seen images of Indus Valley pottery from the Internet, and was shocked at how little information was available online or in print form about them. We did not even know such pottery existed.

The images that I had collected were mostly on auction sites or galleries dealing with antiques, rather than with museums. This led me to believe that the pottery would have been smuggled out over the years or as is the case with many sites the excavation had started pre-independence or by European archaeologists as in the case of Mehergarh, the oldest Indus Valley Site. These artifacts were carried away to fuel the market for art and antiques worldwide.

The saddest aspect of this is not so much that the pottery is no longer in the Indian subcontinent but that there is no comprehensive or reliable information regarding it.

Information on the most enduring material is at best a footnote in the larger picture from one of the oldest civilizations. This cultural disconnect needed to be healed. I wondered if a cultural loss could be the metaphor for this project and be linked to Kintsugi?

Pallavi: Yes, all that comes before us forms our sense of self and identity in many ways. Our history, our ancestors give us a sense of pride in who we are and a connection to the land we belong to. It struck me as deeply problematic that we had never seen these artifacts and as you mentioned that they are not well documented either.

So in a sense, a little bit of our history is unknown to us, and therein lies a sense of loss. From this point on the narrative began to take shape.

Shirley: While going through the images we felt transported to another time. The beauty of the forms and the details in the drawings on them was inspiring, as was the fact that the pottery was anything between 5000 -7000 years old.

Pallavi: It was this sense of wonder at the beauty of the forms and the stories they told that acted as the inspiration and springboard for the visuals of the film.

From very early on I saw the simple line as a visual element: a moving line as a metaphor for the river Indus, on the banks of which this civilisation flourished, and the golden line of kintsugi as a metaphor for healing.

Lines that form a river

Lines that move

Away

Closer

Lines as memory

Lines as time

Lines that breathe

Lines that crack and are rebuilt

A line of gold

A line that heals

A line sublime

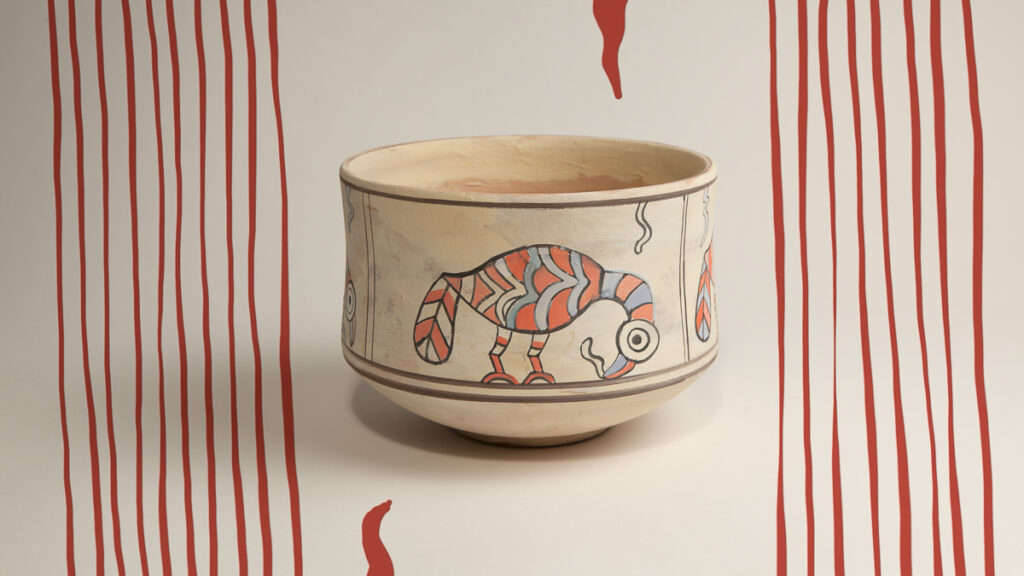

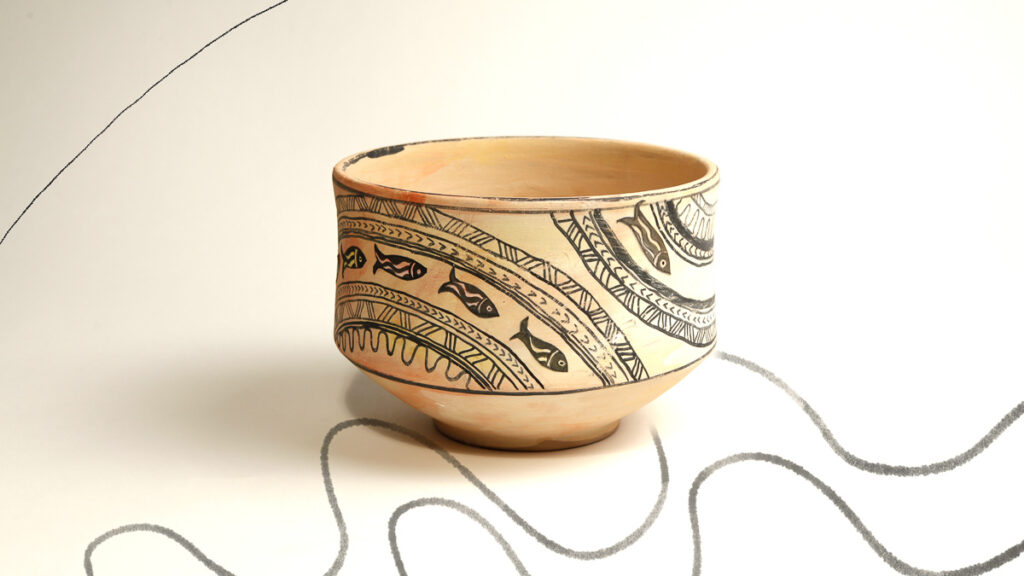

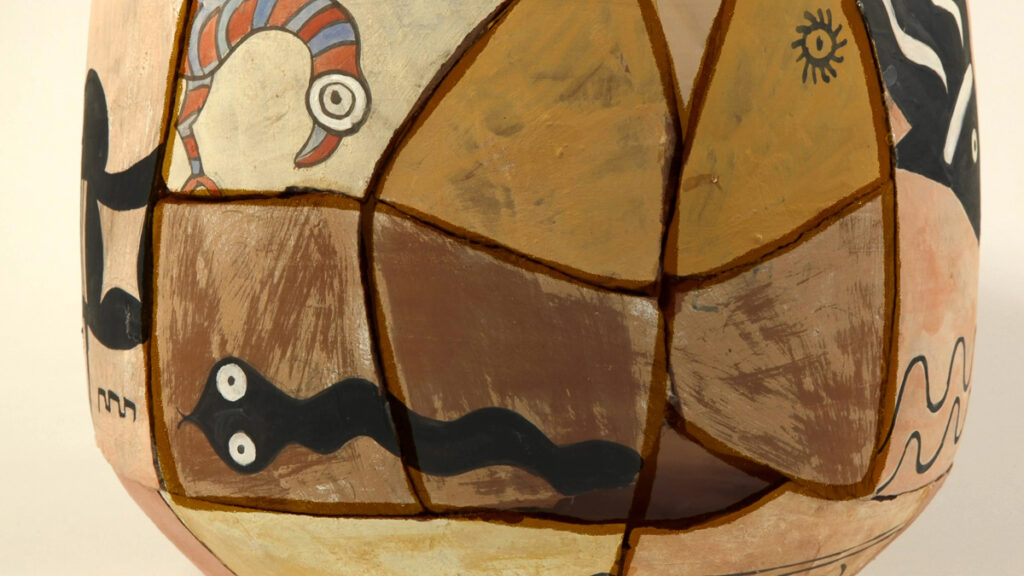

Shirley: From the various examples of ancient polychrome pottery, what stood out were those with animals. We both were drawn to the pottery with the animal imagery more than just pure patterns.

There are pots with numerous tiny ibex painted row after row as if trying to capture a herd. There are birds and snakes and hyenas lions, and antelopes.

However one of the most enduring images for me was the zebu, the humped cow of the Indian subcontinent. The image of the zebu adorns many pots; one particular pot shows the zebu with a bird on its back. This view is still to be seen in rural India, a cow or a water buffalo with a bird on its back is a common sight thus sealing the connection to the present.

We decided to use animal motifs also because the ancient world attributed magic and power to them. Animals were also elevated to the status of ancestors and therefore a large amount of burial pottery was decorated with animal motifs.

Once this decision was taken, we decided to use a typical bowl shape of the period and recreated many of the recognizable animal drawings onto them.

Pallavi: With all the elements in place, the storyline started to fall into place as well. The pot was to be given center stage and lines in different forms would be used throughout the film connecting the narrative visually.

We chose to help locate the film and its geographical context through a map of the Indus valley sites that is again animated on the pot.

The film was then structured into three distinct parts.

Creation

An ode to these fabulous examples of Indus pottery. The visuals and sound would be joyful and the interplay of animated dancing lines, animal forms and a rotating pot would attempt to celebrate creation and life itself.

Loss

The second section would be symbolic of the loss, culturally and historically of these objects, shown through cracks appearing on the pot, followed by broken fragments. At this point time slows down, the lines disappear and we are allowed for a moment to examine what remains, what is left behind.

Recreation

The broken fragments slowly start to come to life one by one. The animals start to move again and these fragments from different pots come together healed by the golden line of Kintsugi. It is an attempt to understand how we can visually lay claim on a part of our collective history by putting the pieces of the puzzle together and in some way bring them home.

- Creation

- Loss

- Loss

- Recreation

Shirley and Pallavi: We needed music to complete the picture and compliment the lyrical nature of the film. We felt instruments like the Ghatam, an ancient Indian percussion instrument, for the soundtrack would be suitable.

Sandeep Pillai a designer, composer, and musician came in at the final stages of our film and breathed life into the visuals with his interpretation of our journey from creation, to loss and finally to rebuilding. He worked with existing instruments and pots and broken fragments and created a soundtrack that transported the visuals and uplifted them. He made the pots dance and sing to the music bringing up centuries of concealed information to the forefront.

At the heart of the film is the river Indus and the civilization that flourished around it. Sindhu – A Subterranean Song is an ode to the ancient creator.

This film evolved during the pandemic over three months, numerous conversations, a number of drawings, and several cups of tea.

About Shirley Bhatnagar and Pallavi Arora

Shirley Bhatnagar is based in New Delhi. She is a design graduate, she works primarily in ceramics. Her studio Irregular beauty is known for humorous work, with social and political commentary. She was the first awardee of the exchange between Indian ceramics Triennale and the British ceramics Biennial in 2019 for the exhibition at Stoke on Trent in the UK.

Shirley Bhatnagar is based in New Delhi. She is a design graduate, she works primarily in ceramics. Her studio Irregular beauty is known for humorous work, with social and political commentary. She was the first awardee of the exchange between Indian ceramics Triennale and the British ceramics Biennial in 2019 for the exhibition at Stoke on Trent in the UK.

Pallavi Arora is a filmmaker, designer, and educator based in New Delhi. She runs a brand called OHPA that makes playful and practical products for children and adults. She also currently runs The Little Picture Project (LPP) that exposes children and young adults to the visual arts with a special focus on filmmaking and photography. Follow @thelittlepictureproject.

Pallavi Arora is a filmmaker, designer, and educator based in New Delhi. She runs a brand called OHPA that makes playful and practical products for children and adults. She also currently runs The Little Picture Project (LPP) that exposes children and young adults to the visual arts with a special focus on filmmaking and photography. Follow @thelittlepictureproject.

Comments

Sindu, an evocative tale celebrating an unknown maker, by accomplished creatives. Smiling to read some known to me makers. A small world really.

So beautiful and heart warming!

Thank you!