Songül ARAL finds a way to connect with childhood objects through miniature looms made by a retired mechanic and his memories.

(A message to the reader.)

My grandfather’s bright brown-red wooden pipe, which turned his white beard yellow, was carried in his pocket for years. He used to fill its tiny slot with tobacco every day, with smoke coming out of the end… right next to it, the tobacco storage container resembling a treasure chest with its niello-embroidered silver lid… Made of wool that my grandmother had hand-painted.

When they were alone with my grandfather, he lifted the glass cover and put the pointy end of the tiny needle on a black record and listened to the music while he glided like a dancing skater… the close friend of the turntable, the sullen-looking grill radio with its bone button and lace headscarf… The glass cabinet in the corner of our living room that no one stops by. Silent guests of the cabinet with shelves…the objects of the traces of the past, like the keepers of time…the pocket watch with a chain left from my father on a lower shelf…I watch the travellers of time in Malatya accompanied by a white snow cover.

After the guests have left, I watch with the same sadness years later. They are like guests from another world, they are watching us, our time travel. We get used to them in deep silence. Our longing for those who have left is replaced by the objects we protect with respect. When the life process in which we came to the world, stayed and migrated comes to an end, we witness that the objects left behind from our lives survive longer than we do.

Well, what if there is no object left from those who come and go as guests? There are many objects in our memory from childhood that we can see when we close our eyes. Can we transform the abstract markers encoded by the mind into concrete objects through our hands?

Let’s watch and listen concretely to the story of Abdullah, who, as a six-year-old boy, decided to keep his memories from being erased from his mind

Denizli is one of the cities with weaving factories (Sümerbank) whose foundations were laid in the Republican era in Turkey. People born, raised or have family roots in the cities where these factories are located are friends with weaving.

Weaver families, who can maintain the influence of the past years in Denizli, know each other closely. Some of them are sizers, some are yarn twisters, some are bobbins. The streets and bazaars of the city, which belong to the weavers, greet the guests with their historical houses with colourful weavings. The cloth producing town of Buldan is world-famous. We weaver academics eagerly await the weaving symposiums to be held there, and we leave the regions and events where the whole town is a weaver, motivated by the purchase of local weavings in our suitcases.

Abdullah is the son of one of the weaver families from Denizli-Babadag whose grandfather, grandmother, mother and father migrated to Istanbul from one of the known big cities of Turkey before he was born (1920).

Abdullah Bey, born and raised in Istanbul, is now seventy-four years old. He retired from the automotive business where he worked for a long time, again in Istanbul, about eleven years ago.

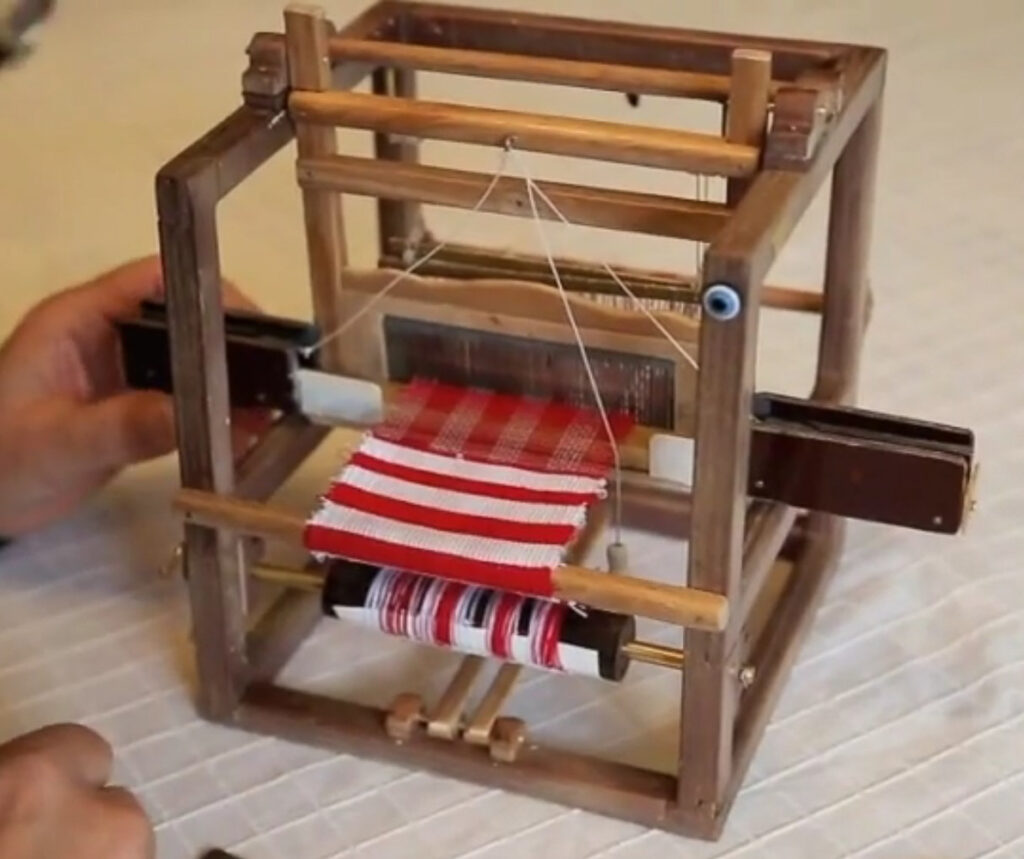

“When retirement starts, it means that the return has begun,” he says. He smiles with the sentence “I aim to spiritually repair the scoldings I heard in my childhood. Retirement was an opportunity for me to make non-perishable looms. I started making miniature looms. They are all handmade. It takes about two months to make one. The workbench and its parts that require fine-tuning take a maximum of four months. When I hear that sound from the workbench when I’m done, I fall into a very peaceful sleep. When I rest my head on the pillow on my bed, i hear “çıkı…çıkı…çık/çıkı…çıkı…çık…” This sound is my lullaby, like my mom’s and grandma’s knees.”

Abdullah remembers witnessing the woven wooden loom still in their house when he finished primary school. He excitedly describes his childhood wandering around the loom, in the imaginary home environment of his mind, among his memories. There are also patterned fabrics that his grandmother wove alternately with his grandfather on the loom at home. Not only does he watch the progress of these weavings on the loom with curiosity, but he also learns and memorizes the dobby, jacquard, whip, pedal and power.

“When they got up from the weaving loom, when they had a lunch break, I would secretly sit on the loom and take the shuttle, the whip attached to the loom with a rope in one hand, I would hold on to the wood with my other hand in order to pull it quickly and make the shuttle go back and forth, and I would try to touch the pedals and raise my feet at the same time. Most of the time I would spoil the whole pattern, I couldn’t get it together, the power frames hanging on the counter would fall to the floor and my grandmother would get very angry, she would give me a wooden bobbin with wire – come on, wrap the weft thread on it- even though I got scolded many times. It was also enjoyable to be subjected to such a cute punishment as winding a bobbin.”

He remembers that his family continued to weave in their childhood home with a loom until 1960, and then the silence began. Since they could not keep up with their speed with the transition to industrial machines over time, the family reduced the production of the orders, their sales decreased and the sounds of the looms ceased.

He states that these memories saved him from falling into a void when he retired about eleven years ago. He adds that when he retires, he constantly goes back to the past, his memories come to life, he forgets most of the past, but he cannot forget how his father sat at the loom with him in his lap and how he weaved.

He focused on the idea of keeping his memories alive as a hobby with a sudden decision, “My constant memory forced me to take action even before retirement.”

First, he made a few wooden miniature looms and paused the construction of the wooden loom, some of which were worn out early. In the future, he focused on making the best craftsmanship, and then he started to make miniatures of industrial workbenches, which caused the migration of his family origins years ago, from brass material and metal.

He transformed the small space on the ground floor of her house into a workshop and completed thirty-two workbenches in the workshop that he calls “My memory room where I store my childhood”.

“I make my little looms, my children, from brass sheet. Brass is a good material, it obeys, I polish when I want, I can give it an antique look when I want. When I add wooden parts, I achieve the result I want in my dreams. I can say that I complete all the work by hand. I cut, file and bend. I don’t scrap any part: I reshape it. I only buy the motors that help the machine move, and I also buy the rubber to connect it. All the others are brass plate sheets, wire, wood that I shaped by hand. I bend, cut, cut, break, try again, like I’m fixing the dial of a watch until the mechanism works.

“This little jacquard pattern maker is one of my favourites. I had to make these things. The current generation doesn’t know them. They see them as toys. I used to watch for hours when I was a child that yarn was fabric on these looms.”

Abdullah states that there is a great interest in miniature weaving looms, which he describes as the children of masters, but he cannot sell them. Nonetheless, he is happy to exhibit them.

Can these miniature objects produce memories of the past that are ingrained in people’s lives? We feel that we have reached the answer to the question. We are partnering with the idea that there should be no waiting for retirement to unleash a productive talent and to spend that talent’s time productively. He recommends that people produce handicraft objects as a therapy method that can achieve healthy results in their engagement in lifelong learning.

Can illustrative memories also be used as tangible objects for the future? We can sustain a healthy life by doing the work we love.

Should we create and tell craft tales or transfer tales to the metaverse universe in order to be in harmony with a young generation who walks among us wearing virtual reality glasses and waving their hands to capture the void? As craft educators, we need to figure this out before we retire.

See more videos here and follow @weaving_loom_machines

About Songül ARAL

I am from Turkey. I live in Malatya. I work as a faculty member in the Department of Traditional Turkish Handicrafts and Graphic Design Department of the Faculty of Fine Arts and Design, İNÖNÜ UNIVERSITY. I continue my field applied studies on traditional folk crafts. Mostly, I focus on our hand weaving, especially carpets and traditional women’s jewellery. I wish you a long life with good health. Email: songularal@hotmail.com or aralgul@gmail.com

I am from Turkey. I live in Malatya. I work as a faculty member in the Department of Traditional Turkish Handicrafts and Graphic Design Department of the Faculty of Fine Arts and Design, İNÖNÜ UNIVERSITY. I continue my field applied studies on traditional folk crafts. Mostly, I focus on our hand weaving, especially carpets and traditional women’s jewellery. I wish you a long life with good health. Email: songularal@hotmail.com or aralgul@gmail.com