© Martin Hill and Philippa Jones, ‘Solve for Pattern’, Albert Burn Saddle, Mt Aspiring National Park, New Zealand, 2012, Image size 774mm x 1160mm, Paper size 914mm x 1280mm, (Pigment dye, inkjet print on Hahnemuhle photo rag paper)

Alasdair Foster writes about the New Zealand duo that crafts emblematic shapes from the landscape to be captured by the camera.

A hare hops across the snow high in New Zealand’s Mount Aspiring National Park. Does it notice the strange forms that have appeared, mysteriously, in this isolated place? Perhaps not, but we do. How did they get here and what do they mean, this diamond, circle, and hybrid of the two?

The three sculptures, fashioned from snow, are the work of Martin Hill and Philippa Jones. This is a form of Land Art, handcrafted from materials found in the immediate environment. It is intentionally ephemeral, constructed from what is in Nature and later returning to the earth. While many other forms of art and craft are made to last, it is the essence of this kind of conceptual creation that it will not. Nor, given its remoteness of location, will it be seen in situ by anyone but those who made it… and any passing fauna with an aesthetic sensibility. It is the mechanical eye of the camera that bears witness and its alchemical memory through which these visual stories are later recounted.

And this is a story about good and bad design.

- © Martin Hill and Philippa Jones, ‘Woven Willow Sphere’, Clutha River, Wanaka, New Zealand, 2011, Image size 774mm x 1160mm, Paper size 914mm x 1280mm, (Pigment dye, inkjet print on Hahnemuhle photo rag paper)

- © Martin Hill and Philippa Jones, ‘Ice Circle’, Lake Wanaka, New Zealand, 2008, Image size 774mm x 1160mm, Paper size 914mm x 1280mm, (Pigment dye, inkjet print on Hahnemuhle photo rag paper)

- © Martin Hill and Philippa Jones, ‘Autumn Leaf Circle’, Clutha River, Wanaka, New Zealand, 2010, Image size 774mm x 1160mm, Paper size 914mm x 1280mm

- © Martin Hill and Philippa Jones, ‘Sculpture No. 2’, Yosemite, USA, from the ‘Fine Line’ project, 1996, Granite particles, Image size 1160mm x 774mm, Paper size 1280mm x 914mm, (Pigment dye, inkjet print on Hahnemuhle photo rag paper)

- © Martin Hill and Philippa Jones, ‘Burning Issues’, Albert Burn Saddle, Mt Aspiring National Park, New Zealand, 2013, Grasses, wire, Image size 774mm x 1160mm, Paper size 914mm x 1280mm, (Pigment dye, inkjet print on Hahnemuhle photo rag paper)

Martin and Philippa met in 1994, on a ledge halfway up a rock face. They became climbing partners and, soon after that, life partners and creative collaborators. Over the years, their working practice has evolved as they travel and share ideas together. Martin is the photographer, Philippa is a skilled weaver and basket maker, but most of the creative making is shared by them both. Carving a sheet of ice, sculpting compacted snow, carefully arranging autumn leaves beside a river, or describing a circle in sand and rocks on a precarious ledge high above Yosemite… their materials are as diverse as the locations in which they make their work, but their symbolism draws on a carefully considered handful of universal signifiers.

Preeminent is the circle, which may also be rendered as a disk, a sphere, or a semicircular arch set in water so that the reflection completes the orbicular whole. This represents the fundamentally circular systems found in nature, where nothing is wasted, and all things grow up from what has previously lived and died. The second is an angular shape—a triangle, square, or diamond—which symbolises the linear design adopted by many industrial systems following a take-make-discard model of production. Economically efficient in the short term, such systems are, as we are coming to understand, reckless in the longer term. The third is a simple humanoid form made of moss, bark, grasses and other plant materials suggesting humankind’s troubled but inextricably intimate relationship with Nature.

Entitled Solve for Pattern, the image from Mount Aspiring National Park that heads this article is a kind of aesthetic math in which the diamond within the circle refers to the urgent necessity for human systems to be adapted to the sustainable efficiency of natural ones. As Martin Hill explains: “in the terminology of design, ‘solving for pattern’ results in solutions that increase balance and harmony, and improve the health of the whole system.”

Concept, craft, design, and engineering are all interwoven in their artmaking.

© Martin Hill and Philippa Jones, ‘Synergy’, Lake Wanaka, New Zealand, 2010, Image size 774mm x 1160mm, Paper size 914mm x 1280mm, (Pigment dye, inkjet print on Hahnemuhle photo rag paper)

In 2009, Hill and Jones were invited to participate in a project to make work in the area around Lake Wanaka on New Zealand’s South Island. As inspiration and focus, the local Māori community introduced them to the history of the place, and it was these stories that they then creatively explored.

“We chose to respond to the origins of the name,” Martin explained. “In the Māori language it means ‘place of learning’. We decided to learn something new.”

“In my research into naturally evolved design, I learned that the modes of construction that make the strongest forms with the least material harness the forces of compression and tension. [The American architect and systems theorist] Buckminster Fuller named this system ‘tensegrity’ [a portmanteau of ‘tensional integrity’]. The sculpture we built—which was made from dried reed sticks held apart in suspension by a network of linen threads—used these principles to create a semi-circular structure. This was installed on the lakefront and the reflection in the water completed the circle. It is an example of synergy—the creation of a whole that is greater than the simple sum of its parts—which, in this case, is an emergent property of tensegrity. In this way, the sculpture is itself a demonstration of the concept it represents as an artwork.”

- © Martin Hill and Philippa Jones, Philippa Jones working on ‘Sculpture No.1’, Mt Ngauruhoe, New Zealand, from the ‘Fine Line Project’, 1997, Image size 774mm x 1160mm, Paper size 914mm x 1280mm, (Pigment dye, inkjet print on Hahnemuhle photo rag paper)

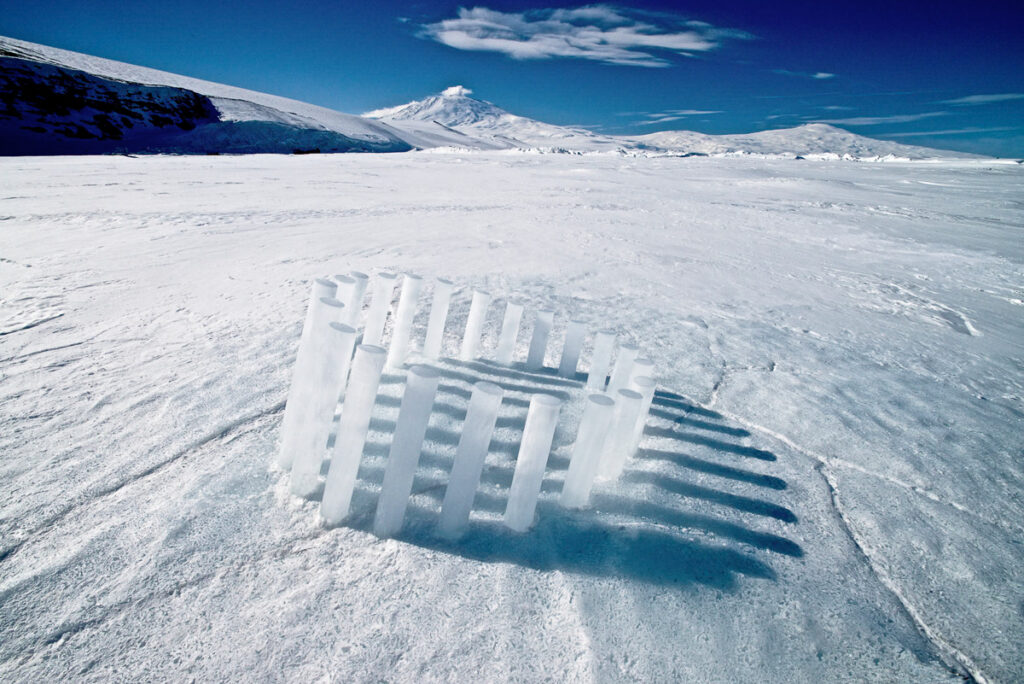

- © Martin Hill and Philippa Jones, ‘Sculpture No. 10’, Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica, from the, ‘Fine Line Project’, 2014, Image size 774mm x 1160mm, Paper size 914mm x 1280mm, (Pigment dye, inkjet print on Hahnemuhle photo rag paper)

Together, Hill and Jones have made many installations and creative series in New Zealand and other parts of the world. But their most ambitious to date has been Fine Line, a remarkable project that is, quite literally, global. Twelve ephemeral sculptures and land-art installations were created at various locations around the world. Passing through the polar snows and the equatorial mountains, the European alps and Pacific archipelagos, the points lie on an arc encircling the earth. In its range of geography and span of time, its sheer magnitude takes it beyond physical experience for all but those who were directly involved. Each work is crafted from the materiality of place, inspired by its genius loci. It is undeniably physical, yet it can only be experienced virtually, through the photograph, as an image of an idea, just as the encircling line that connects the twelve constructions is the creative evocation of a concept that only exists on a map.

Through this layering of symbolism, allusion, conceptualism, and practical demonstration, through their remarkable scale of vision and precision of craft, Martin Hill and Philippa Jones urge us to think deeply and change fundamentally. These are existential threats we face. Yet they speak not with the shrill cry of Cassandra, but rather the quiet voice of the rational poet. Their sculptural forms harness the very processes they promote, creating images that are conceptually grounded, elegantly demonstrating Nature’s circular systems of truly sustainable design.

For all our artifice, we exist within Nature, as do all living things.

© Martin Hill and Philippa Jones, ‘Melting Ice 2’, Wanaka, New Zealand, 2007, Image size 774mm x 1160mm, Paper size 914mm x 1280mm, (Pigment dye, inkjet print on Hahnemuhle photo rag paper)

——

The book, ‘Fine Line: Twelve Environmental Sculptures Encircle the Earth’ [ISBN: 9781988538914] is available from Bateman Books, New Zealand and internationally through Fishpond.

About Alasdair Foster

Dr Alasdair Foster is a writer, researcher and award-winning curator working in many regions internationally. He is the publisher of Talking Pictures, interviews with photographers around the world, ambassador to the Asia-Pacific PhotoForum and an adjunct professor in the School of Art of RMIT University, Melbourne. He has twenty years experience heading national arts institutions in Europe and Australia and over thirty-five years of working in the public cultural sector. He was previously founding director of Fotofeis, the international festival of photo-based art in Scotland (1991–1997), director of the Australian Centre for Photography (1998–2011) and, until 2022, Professor of Culture in Community Wellbeing at the University of Queensland, Brisbane. His previous roles include managing editor of Photofile magazine, president of the Contemporary Arts Organisations of Australia, and chairman of the Conference for European photographers. Alasdair is a steward of the Darkoom.

Dr Alasdair Foster is a writer, researcher and award-winning curator working in many regions internationally. He is the publisher of Talking Pictures, interviews with photographers around the world, ambassador to the Asia-Pacific PhotoForum and an adjunct professor in the School of Art of RMIT University, Melbourne. He has twenty years experience heading national arts institutions in Europe and Australia and over thirty-five years of working in the public cultural sector. He was previously founding director of Fotofeis, the international festival of photo-based art in Scotland (1991–1997), director of the Australian Centre for Photography (1998–2011) and, until 2022, Professor of Culture in Community Wellbeing at the University of Queensland, Brisbane. His previous roles include managing editor of Photofile magazine, president of the Contemporary Arts Organisations of Australia, and chairman of the Conference for European photographers. Alasdair is a steward of the Darkoom.