Bryan Baker recounts the day a Czech master arrived at his door and passed on the secrets that would enable him to develop the knife that is sold by hundreds of thousands around the world.

Quest for the lost knife

On my father’s side, there was a family of business people. One uncle owned a very large knitwear factory in the 1970s. Another uncle was a paper merchant. My father and his uncles worked in the family’s cardboard box manufacturing factory in the 1960s. I was surrounded by business people and I learned a lot watching them operate. The same is happening now with my two daughters.

When I was about 12 years old, my parents moved out to a farm. On the first day, I found a Second World War bayonet in the hay barn. When I got home from school that day, my father had given the bayonet away to someone because he thought it was dangerous.

To make up for this loss, I bought a small pocket knife that I used to carry around on the farm. But within a few months, I lost it too. Those two knives were lost to me.

When I went to high school, they had a metalwork project to make a knife. The class of about 30 made knives and, of course, my knife got stolen.

So I went back to night school and I made another two there. And then when I had my first job soon, I was making knives at home in my spare time and I was selling a few. My first break came with my uncle who bought me an order for 40 or 50 knives for butchers and fish and chip shops.

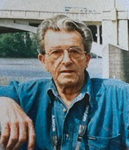

Heavenly blue sky (1927 – 2020)

That was my first order and I got going from there. I’d been going for about five years before the Czechoslovakian guy walked in the door. But I don’t think I would have lasted much longer after that. I would have given up. You can try to learn from books. It’s got to be hands-on. Bob was a trained cutler and he had a business. It was good to learn off him.

That was my first order and I got going from there. I’d been going for about five years before the Czechoslovakian guy walked in the door. But I don’t think I would have lasted much longer after that. I would have given up. You can try to learn from books. It’s got to be hands-on. Bob was a trained cutler and he had a business. It was good to learn off him.

Bob’s name in Czech is Bohumil Nebesky, which means “heavenly blue sky”. He had been offered support in Australia to set up the cutlery industry on Gold Coast but decided to stay with family in New Zealand. He taught me the unique hardening and tempering process which gave my knives a special edge of strength and durability.

Peasant knife

The peasant knife is based on models used in Bohemia and Bavaria 3-400 years ago. It’s easy to use, easy to carry and to open. It just appeals because it’s simple. It’s not from any particular country, but we give a bit of a blurb that romanticizes it.

It’s been in production for 27 years. We’ve sold hundreds of 1000s of them. They’ve gone all over the world. They’ve got a good following on the internet. I don’t intend to change it. It’s a successful product. Two of our most successful products selling to the United States are our cheapest product which is the peasant knife and our most expensive product, which is the Von Tempsky Bowie Knife

Locally made

We use a very good Swedish carbon steel: the old fashioned steel. The simplicity caught on and we sell many 1000s of knives a month. There are eight people working here.

We have contracts with a lot of timber mills and we buy the steel as used bandsaw circular saw blades. We cut them by laser. And then once they come back from laser cutting, I do all the heat treatment myself. I always heat treat all the knives on the premises.

I have a big German grinding machine, proper cutlery grinding machine, and then we sharpen them, we put the handles on them and then they get packaged, It’s quite a simple process to make a piece in life. The total time to make it from A to Z would be about six minutes.

The wholesaler in New York said to me once he said, “We’re not buying your knives off here because they’re made in New Zealand. You see we’re buying them off here because they’re not made in China.”

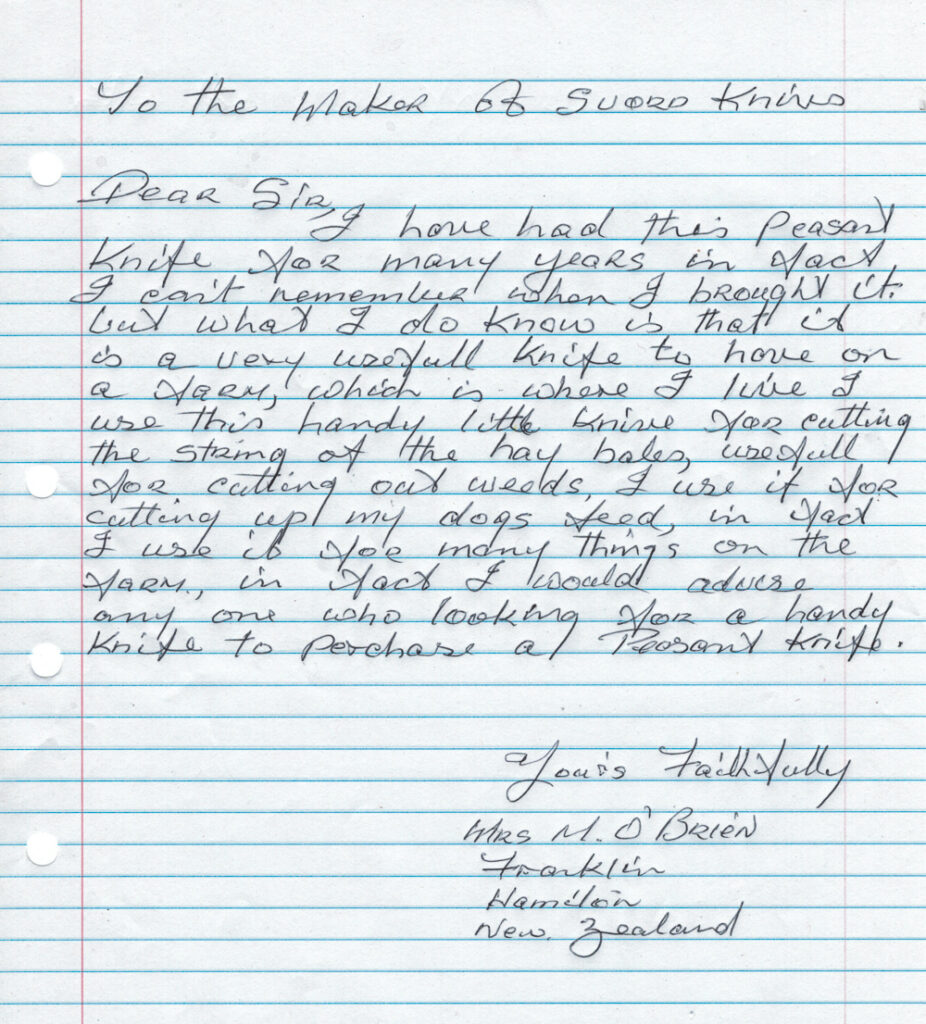

Mrs O’Brien

Visit www.svord.com and follow @svordknives