Through six projects, weaver Sara Lindsay interlaces the warp of solitude with the weft of community.

I think of all of my work as a kind of conjunction between visual art concepts and material culture where the histories embedded in the materials and the way things are made are critically important to the content of the work.

Anne Wilson, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, 2020, www.annewilsonartist.com

For over three decades I was known principally as a tapestry weaver, through my work at the Australian Tapestry Workshop (ATW) and in my own studio. However, the last few years have seen an expanded approach develop which has involved photography, stitching and performance as well as weaving and drawing. I have intensified my interest in the relationship between weaving, drawing, walking, the social history of textiles and art and social engagement. This has become evident through my solitary studio projects as well as those where I have actively sought engagement with others.

Solitary 1 – The Skirts Project

Recently I was walking down a suburban street in Melbourne. A man was walking toward me and I instantly recognised him as the person who I hold responsible for the first photograph I took in 2016 which led to my four-year-long Skirts Project. With the confidence of age, I approached the man and asked him if he had a young daughter. He said he had. I then proceeded to tell him how I had tried to use my iPhone to record details of my daily walks. How I had become disenchanted with the well-composed but mundane images I was taking until the day I had spotted him with his daughter and somehow a switch turned on in my brain and a new study began. I talked about my reticence in revealing the head and face of my subjects. Craig reached out, told me his name and shook my hand. His face lit up and he declared that he was very happy for me to use the image in any way I wanted to.

So what was it about this photograph that captured me? Certainly, it was my eye for cloth—its colour, pattern, weight and the way it moves. The contrast of the studded leather jacket against the soft tulle of the pink skirt. Then the environment in which the figures were placed—the graphic connections between the fluid textiles and the rigid surface of the road. And the immediacy of the shot. Using a small iPhone which fitted comfortably in my hand, and with the sound turned off, I could move quickly and discreetly. I needed to be on my own and intensely observant.

Speedy, easy movement in skirts is real. Legs pivot at the hips and hinge at the knees and thus the speed of gait and fluidity of movement is massively eased by a wrap of fabric that skims the pelvis and falls loosely around the legs.

Kate Fletcher: Wild Dress, Clothing & the natural world, Uniformbooks, 2019

As I took more and more photos every day, I became increasingly aware of the discussion around the “voyeuristic” nature of photography. Should I be photographing people without their permission? How are so-called “street photographers” regarded now? Did those women sitting in a café know that Vivian Maier was snapping them? In her book Girl on Girl: Art and Photography in the Age of the Female Gaze, Charlotte Jansen says “they (women) see the world differently—in just as much colour and nuance. We are beginning to see that world, everywhere we look”.

Many of my male friends would say “of course, I couldn’t do that” and I decided that was exactly the point. As an older somewhat invisible woman, I felt a sense of agency and strength in documenting and celebrating the energy of women in my local neighbourhood in Melbourne, and during several visits to Kyoto and Lisbon. I used Instagram as a diaried recording of these images. Some were magnified and shown at Stephen McLaughlan Gallery in Melbourne and a selection of 100 images formed the exhibition Perambulations which was shown on-line at www.museumofopenness.com.

These women are real. Both feet on the ground, they are their story and we do not need to know where they are going or where they have come from. The step is the quintessential symbol of movement. The camera makes most sense when it freezes the constant continuation of life. A photo of a landscape, a house or a portrait does not do that as clearly as a photograph of a step.

Alf Löhr, Curator, Museum of Openness

Community 1 – COVID 19 Walking for Nurses

By May of 2020, life in Melbourne was consumed by the pandemic. During our long lockdowns, we were allowed to leave the house for two hrs per day. To keep our minds and bodies healthy my daughter and I walked together every day within our restricted 5km zone.

I was struggling with the recent death of my younger brother and unable to focus on the delicate, abstract tapestries I had begun in Japan and continued to work on in Lisbon. I needed to find a meaningful way to remain connected to people outside of the house and the country I was restricted to.

My mother had been a young nurse in World War II. She worked in a hospital in my birthplace of Oxford(UK) which received soldiers straight from the front. It was challenging work and had a long-term impact on her mental health.

I decided that I would develop a project to thank the nurses of the world. I found a large bolt of pin-striped fabric in my studio and some pink and white gingham. I also had a collection of pre-worn black and white striped t-shirts. There was enough fabric to make ten skirts. With the purchase of a few more t-shirts, ten uniforms were constructed. I retained one uniform for myself and invited eight artists and one former psychiatric nurse, all friends of mine, to become the custodian of a uniform and to embroider designated text onto the skirts. This included #thankyounursesoftheworld and #covid19walkingfornurses. This was followed by the construction of a further 90 black and white gingham scarves which were distributed throughout Australia, Japan, Portugal, America, France and the UK with Farsi, Greek, French, Urdu and Filipino used to embroider the text on some of the scarves. Custodians of the uniforms and scarves were asked to document their stitching and to walk whilst wearing the embroidered items.

On July 1, 2020, a small group walked through my suburb of Richmond to officially launch Covid19 Walking for Nurses. Since that time I have received hundreds of images, using Instagram as documentation as well as a way of sharing the experience amongst participants and attracting new people, previously unknown to me. Thanking nurses through the meditative act of stitching and walking proved to be the perfect combination of process and intention that made us all feel part of a universal community during such a strange and dislocating time. Many participants had family members or friends who were nurses. They were able to observe clearly the impact that Covid was having on those so close to them. Exhaustion, desperation at times, yet an endless supply of care and dedication.

A set of seven scarves and ten images of participants as far afield as Kyoto, the Nullabor Plain and Brooklyn, NY were shown in the Wangaratta Contemporary Textile Award. Several attempts were made to gather together Australian participants, only to be foiled by repeated lockdowns and illness. Eventually, a walk took place in Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens on July 3, 2022. Custodians of uniforms and scarves came from interstate and throughout Victoria. I finally met people I had only communicated with through social media. It was a joyous occasion, made particularly significant by the presence of a nurse who had worked in ICU throughout the pandemic.

Solitary 2 – Tatami Drawings

A HOUSE SYMPATHETIC to my preoccupations and repetitions and observances; a house whose walls and floors and furniture diligently, doggedly, interminably order themselves around my daily practices – My daily handiwork.

Sara Baume, Handiwork, Tramp Press, 2020

During 2020 and 2021 I spent many hours walking alone with my two embroidered scarves for nurses, photographing them in the strangely quiet and surreal empty city. Over time I regained the high level of concentration required to continue producing the series of small tapestries, titled Tatami Drawings, that I had commenced in my studio in Kyoto.

In 1981, as a young woman, I studied Kasuri weaving in Japan for six months. The modern school on the outskirts of Kyoto, like many modern homes in Japan, had a tatami room and this was where I sat for several days wrapping thread tightly around a pre-dyed warp to form a resist when re-dyed. I have also spent many hours during my several visits to Japan sleeping on tatami. It is firm, but has some give and it has a very particular smell. The strong hemp binding can be red or black, which forms a dramatic pattern across large spaces. My Japanese friend brought tatami with her to Australia, to remind her of home.

Before I returned to Japan, I had spent some time in a slightly larger studio space in Lisbon. There I used the objects in the studio as subject matter. I made rubbings of every surface, including an old wooden ironing board with a scratched metal section that had absorbed the heat of the iron. I imagined the sheets, the shirts and the table cloths that had been smoothed on this simple, elegant object. I rubbed chalk over the plastic woven table mats, using paper from the Paula Rego Museum. I folded large sheets of brown paper into structures and applied pharmaceutical products that had been left by a previous tenant. Texture and materiality consumed me on a daily basis as it served to connect me to my new home, thousands of kilometres from my house in Melbourne.

It was not surprising that I responded to my Kyoto studio dwelling in a similar manner. My studio was the size of six tatami mats, each one measuring 0.9 x 1.8m. I began making a series of drawings by placing paper directly onto the woven tatami and drawing lines or making rubbings in response to the linear texture. I then purchased several small wooden frames of different sizes and warped each one with a different size warp and spacing. With the additional purchase of plant-dyed yellow cotton and hemp from the local temple market, I began to slowly weave, with just a sideways glance at the delicate works on paper.

I walked during the day, exploring the gardens and streets of the ancient city. In the late afternoon, I seeped my aching body into the hot waters of the many sentos hidden in the back streets of Kyoto. Alone in my quiet cocoon, I wove late into the night, handling the evocative materials and thinking about the enduring presence of traditional and modern textiles I had seen on the streets whilst walking. I remembered the finely woven silk kimono cloth I had made as a student at the Kawashima Textiles School, and how an extra two cm had been added to the width to accommodate my long thin body. I re-lived my trips to the tiny islands in the Inland Sea to experience the Setouchi Triennale, where contemporary artworks were shown in skilfully renovated barns or almost derelict, abandoned houses. I dwelt on the displays of textiles, ceramics and baskets in the various Folk Craft (Mingei) Museums I had visited in Tokyo, Osaka and Kurashiki and pondered the ongoing existence of these domestic crafts, many of which are already dying out as people move to the cities and purchase cheaper, mass-produced items.

As I write I continue to work on my hand-woven Tatami Drawings. The weaving is fine, slow and gentle on my ageing body. The specific Kyoto cotton, the colour of ginkgo leaves in autumn, is nearly finished. But the series continues, slightly transformed. Japanese bamboo paper yarn is sometimes used for warp and the beautifully wound balls of hemp will unwind a little further.

Community 2 -The Ginkgo Project

Six ginkgo trees that were within a short radius of the atomic blast on Hiroshima in 1945, survived against all odds. As a species, they are ancient and strong. I arrived in Lisbon in November 2019 to undertake a four-month residency with A Avó Veio Trabalhar (Grandma Came to Work, www.fermenta.org). The ginkgo trees were turning yellow. I decided to call the work undertaken during my residency The Ginkgo Project.

The previous year, whilst visiting Lisbon in search of the paintings of Paula Rego, I discovered this organisation which provides a creative hub for people over 60. “Old is the new young” is their slogan. Many of the participants are in their 80s and have had challenging lives. Like the ginkgo, they are great survivors. I offered to run some simple weaving classes and I was warmly greeted by the “Grannies”. I felt an immediate affinity with this textiles-based organisation and as a result, was offered a residency by co-founders, Susanna Antonio (designer) and Angelo Campota (psychologist).

Throughout December 2019 and early January 2020, I spent time in the large studio, working in the mornings alongside Patricia and Rosaria, who were sewing surfboard covers from coffee bags that had been donated. In the afternoon more women arrived to embroider or crochet, and to share stories, laughter and song. Many of them had commenced embroidering men’s black handkerchieves, with messages addressing domestic violence. These were to be shown on TV on Valentine’s Day and had been commissioned by a channel, whose previous CEO had been accused of domestic violence.

We understand age as a power to be unleashed. Each elderly person has an individual talent, aspiration and passion in which we believe and nurture.

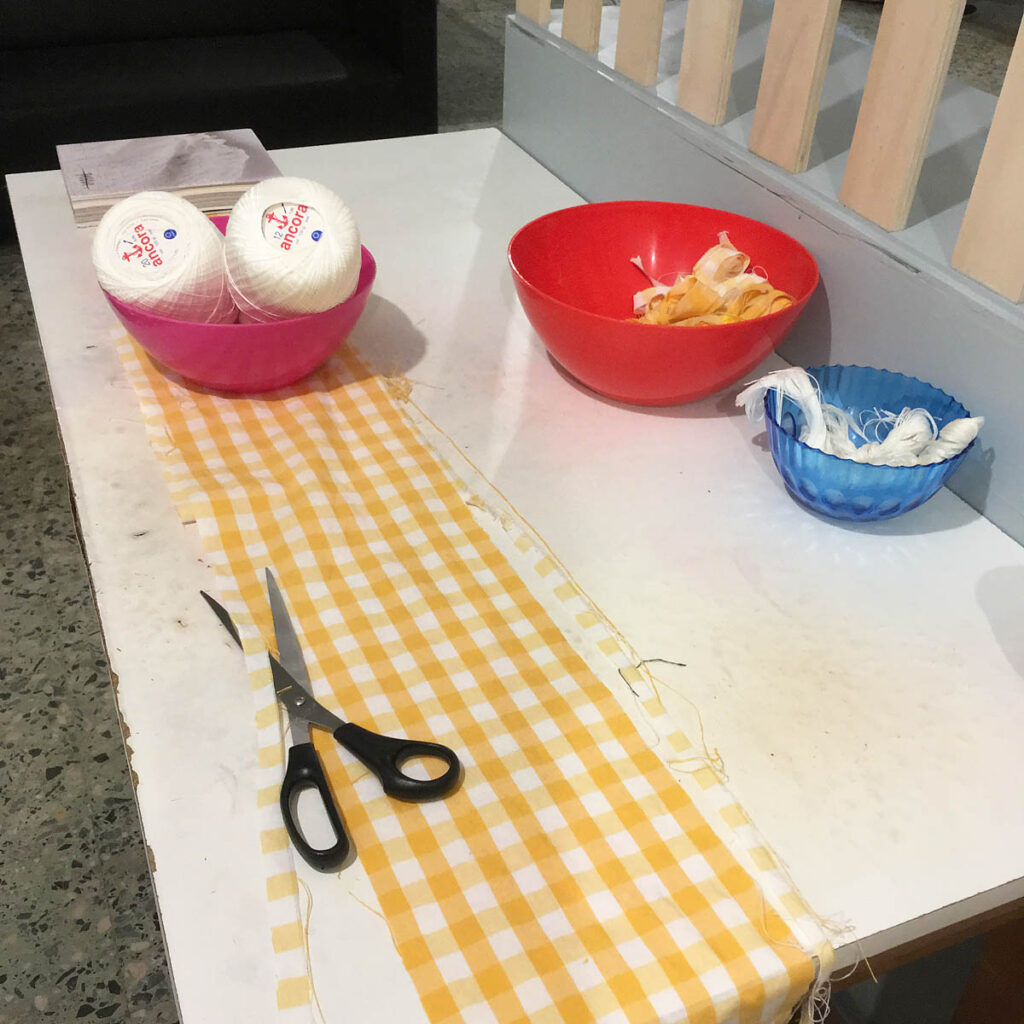

I began preparing a project that, through a collection of tapestries and a handmade book, would tell the stories of these women’s lives in a variety of ways. I decided to return to the fabric I was so familiar with and believed to be commonly used in most Portuguese homes. Gingham, the fabric of tablecloths in Portugal, was easily obtained. Four wooden frames were warped up, using recycled yarn from the large collection that had been donated. I commenced weaving, leaving wide bands of woven white cotton that would later be embroidered by the Grannies. I cut up metres of yellow and grey gingham on which the women would write something about themselves, or perhaps a message, before the fabric was immersed into the body of the weave. A cloth label would then be attached naming each contributor. The fourth and largest loom also left white spaces for embroidery and the women were invited to weave the gingham I had asked them to bring from home.

Patricia and I planned to make tunics from the same gingham and have a “mock tea party” in the local marvellous tea shop. Unfortunately, this did not eventuate. In February I had to return to Melbourne for family reasons and by the time I was able to go back to Lisbon, Covid19 had changed our lives. But I have been in constant communication with the organisation and shall return to Lisbon this October to resume the residency, to exchange skills, to celebrate ageing and to share cultures and language, through the connecting lines of thread.

Shuklay Tahpo & Mu Naw Poe, Free Weaving Exhibition, Wangaratta Art Gallery, 2019; photo: Sara Lindsay

Community 3 – The Karen Tapestry Weavers

Now I want to tell other people that no matter who you are, where you are from that you can achieve your goal if you try. I’m proud of myself and have made my family proud too.

Munaw Poe

This deep connection through thread has also been evident in my work with a group of women from the Karen Community in Melbourne. The Karen are an ethnic minority group from Myanmar (Burma) who were forced to escape to Thailand, after being persecuted by the Burmese Army.

In 2013 I ran a tapestry training program at the ATW for a group of Karen women. On completion, I started visiting two of the women in their homes. I continued to teach them the basics of tapestry weaving, initially every two weeks, then every month until they were self-sufficient enough for me to visit only when they had tapestries they wanted to show me. The weaving team has now expanded to four, which includes three generations from one family. The weavers do not work from pre-determined designs. They have a rich tradition of weaving in their culture and they proudly wear traditional clothing at all celebrations. However, the vibrant designs that appear in their tapestries are a long way from the neat, repetitive patterns of their traditional cloth. The designs come from the weavers’ imagination and the constraints and possibilities of the tapestry process. They are woven directly onto the loom, evolving as the tapestry progresses.

Since 2014 I have organised several exhibitions and demonstrations for the Karen weavers in Melbourne and regional Victoria. In September the exhibition Full Circle will be held at the ATW. Evenings for me are now spent providing uniform finishing and hanging systems to the tapestries, a large task but an important one that connects me to their makers in such a tangible way. It has been such a privilege to get to know Cha Mai Oo, Mu Naw Poe, Paw Gay Poe, Shuklay Tahpo and their families. I have learnt about their culture and their life experiences. In return, the making of tapestries has introduced them to many aspects of Australian life and art. It has given them a sense of independence and pride in what they have been able to achieve.

Tapestry weaving has provided solace. The handling of the soft yarn and the concentration required interrupts memories of suffering and the loss of their life in Burma. Flowers of the Six Months, Falling Leaves, Seedpods; the titles of their tapestries reveal the importance of the weavers’ connection to nature and the village life of their youth.

“Slowly, slowly’’ is our motto. No pressure, no stress. Yet the tapestries keep coming.

Solitary 3 – Plant Stories

Walking, collecting, recording, observing, reading, learning, weaving and drawing – lines, stripes, cotton and linen – plants, flowers, leaves, and colour; all preoccupy me on a daily basis as I prepare new work for an exhibition in Canberra called Plant Stories. Curator, Valerie Kirk, has invited a group of tapestry weavers to respond to the genre of medieval Mille Fleur tapestries, the designs of which incorporate a complex woven background of European plants. We are asked to reimagine these with Australian natives. I have chosen to interpret the brief by observing the native plants in my highly urbanised environment. I am following the route of the No 70 Tram, which passes the end of my street. It travels from the dense high-rise development of Docklands to a large expanse of parkland, aptly named Wattle Park.

I collect small specimens that I match with samples of cotton and linen, marking the plant’s colour when it is fresh. After varying amounts of time, I record the way in which the colour changes when the plant dries out. Sometimes this happens almost overnight, but mostly it takes a few weeks. These colours will be woven into two tapestries, using bleached white linen as the background for WET and unbleached linen for DRY. Simple lines or stripes will tell the story.

Previously I only saw Wattle. I have now learnt that there are thousands of species. I have discovered many public parks and delved into their histories, seeing a distinct shift away from the elms, oaks and beeches, agapanthus, acanthus and lilies of the Victorian era to flowering eucalypts, bottle brushes, grevilleas and kangaroo paws, as well as areas devoted entirely to local indigenous plants.

Sara Lindsay, Walking the warp, the Cyclamen Project, a collaboration with Gosia Wlodarczak, 2019; photo: Longin Sarnecki

Reflection

For decades I made tapestries based on predetermined designs that encompassed a personal narrative and used specific materials that “carried” my story. Gingham cloth was torn up and rewoven to symbolise the dislocation and restructuring of a migrant’s life whilst cinnamon sticks conjured up the presence of my mother’s birthplace, Sri Lanka. Over the last few years, I have become more interested in the intuitive response to simply “drawing” with thread on the loom—the particular properties and associations of the thread, the relationship between the warp and the weft, and the act of warping. This involves the rhythmical process of winding thread around a frame, aligning each thread with precise spacing and maintaining just the right even tension. This is followed by testing out the perfect balance between the warp and weft which allows the weft to compress tightly and form the surface image. The warp can be thick and the weft thin, but beware of the warp being too thin for the weft.

I remember the hours I had spent as a weaver at the ATW walking from one end of the large studio to the other, winding the coarse warp thread around a nail, retracing my footsteps back to the starting point, whilst listening to the rattle of the large cops of seine twine rolling against the metal rods of the warping frame. Then tying a slip knot, cutting the warp free, chaining it and placing it on the bar of a large tapestry loom, sometimes as wide as seven metres. What did I think about as I performed this highly repetitive and bodily act of walking, sometimes as a solitary pursuit, sometimes with a fellow weaver? Often this process provided a space in time between one project and the next. A time to reflect on the approach to be taken on the new tapestry, to speculate on future projects, or perhaps simply some timeout, allowing the walking to generate a contemplative flow.

Wind-Up: Walking the Warp was produced in 2008 at the Rhona Hoffman Gallery in Chicago. Over six days, (Anne) Wilson directed nine participants through the labor of walking a forty-yard weaving warp on a seventeen-by-seven-foot frame. This collective action was informed by a research document prepared by the artist that included sections on walking meditation, the design of safety cloth, and drawing studies of various warping processes. Wilson organised the production space to involve discussions on time and labor, healthy eating, and frequent breaks for meditation.

Anne Wilson, Wind/Rewind/Weave, Chris Molinski, WhiteWalls, October 2011

The repetitive practices of weaving and walking provide the time and pace to reflect on my life and ongoing engagement with making and thinking. I wonder about my need to search—to search for materials: gingham, cinnamon, rubber bands. And how I love the tension in the search and then the material’s subsequent transformation. The search for writers who speak to me, who provide patterns of thought that trigger ideas for new work or a context, not previously considered, in which the newly made work may sit.

I wonder what attracts me to the slow pursuit of weaving and keeps it interesting for me, how this making of cloth is perceived by the wider world and how there seems to be a fresh interest in textiles. Indigo dyeing is no longer simply a way of making colour but carries with it stories of slavery. The Gee’s Bend Quilts from Alabama are now seen in up-market galleries. The Tate in London has exhibited the weavings of Lenore Tawney, Olga de Amaral, Magdalena Abakanowicz and Anni Albers, all of whom had such a strong influence on me in the early 1970s. First Nations’ weaving emanates contemporary power with deep ties to history and cultural practices.

Perhaps my primary role in life is to continue mentoring the young, honing their textile skills and encouraging them to find ways of keeping these important holders of history, culture, and metaphor alive and relevant to the times we live in. After all, we have been wrapped in cloth as babies, we adjust the temperature of our bodies by the cloth we choose to wear and many of us treasure a textile that has been passed down from generation to generation.

I’m just looking out of the window now to the washing hanging on the line and thinking about the intense feeling I get from seeing the striped doona cover just folded on the line and draped. I know that that cloth has covered my body …..it is the feeling of intimacy.

Sara Lindsay from an interview with Kay Lawrence, 2019

About Sara Lindsay

Sara Lindsay lives and works in Naarm (Melbourne). She is currently weaving small tapestries for Drawing the line, a solo exhibition opening on September 17 at Barometer Gallery in Sydney. She will be organising a series of walks in Sydney and Lisbon to “Thank Nurses of the World”. Follow @slindsay.studio

Sara Lindsay lives and works in Naarm (Melbourne). She is currently weaving small tapestries for Drawing the line, a solo exhibition opening on September 17 at Barometer Gallery in Sydney. She will be organising a series of walks in Sydney and Lisbon to “Thank Nurses of the World”. Follow @slindsay.studio