I recall Western Australia as a place of wonder. Growing up in a Perth suburb, we learnt that our state had the largest collection of wildflowers on earth. The kangaroo paw is its ubiquitous emblem, featuring in crests, tea towels and souvenir decals. Holidays would be planned around wildflower season, to enjoy the feast of colour that miraculously emerges from its arid soils. But with the measure of time, this pride thinned. I looked around at the Cadillacs cruising around glitzy Perth. A question began to creep in: what had we done to deserve this bounty?

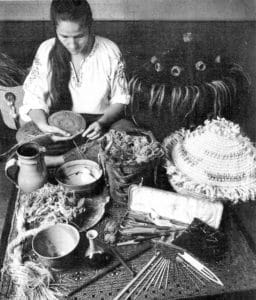

This question was dormant for thirty years until I met a curator friend Gary Warner at Museum Victoria. He’d brought a basket to show me, which interweaved a dense variety of fibre alongside wool and cloth, adorned with seeds. I’d never seen anything like it. It was like a kind of bush expressionism: it spoke of a deep immersion in nature. The artist was Nalda Searles. I had to meet her.

Fifteen years of friendship later, I’m sitting in her Middle Swan home. It’s a midden of objects, all made with purpose. Her soft-boned dog has barked at me, sniffed tentatively, then given me a good licking in welcome.

Nalda and I have been on many journeys. She’s pointed me to a path in which the bounty of the great West can be shared by its settler and Aboriginal inhabitants. I’ve witnessed her sitting easefully in bush camps swapping ideas and techniques with NPY women along the tjanpi trail. And I’ve listened to dozens of other artists recount how their lives have been changed after one of her workshops. In their creative response to the bush, I glimpsed a more appreciative way of living. That left me curious to better understand where Nalda comes from. Is it an idiosyncratic meander, or a common story that reveals another side to the extractivist state?

Nalda grew up in Bullfinch, a town in the eastern Wheatbelt, three hours drive from Kalgoorlie. One of six girls, she left school at 15 to undertake training in psychiatric nursing before taking off to travel through Africa, Asia and Australia. She returned in 1975 looking for a medium of creative expression. A short course in macramé in 1979 introduced her to the manipulation of materials with string. She then taught herself to weave baskets. This much I knew. But how did she forge a vocation as an artist?

Over the years, there were two names that kept recurring in our conversation. I hoped that better knowledge of Nalda’s relationship with Eileen Keys and Pantjiti Mary McLean might reveal a broader context for the emergence of this singular fibre artist.

Listening to Nalda tell stories is an enchanting experience. She speaks with a lilt that is warm, thoughtful and without pretence. Her stories often revolve around first meetings, heralded by a distant call. So she recalls back in 1982, hearing a voice from her back door – “Who’s Nalda?” It was Eileen Keys, the godmother of West Australian ceramics. Having learnt the craft at London’s Chelsea Art School, she formed a coterie of artists during the 1940s who were committed to making local original work. Keys had a strong interest in minerals.

As often happens, Keys’ commitment to place had come from elsewhere. Impressed with the stoneware in London, she went to mineralogist a gem shop to source interesting materials. The owner said to her, “You should go back to Australia and use your own rocks. They are the most important thing for you.” She took his advice and travelled around Western Australia collecting minerals, especially uranium. She set up a ball mill back home to crush rocks for glazing. Attendance at the World Crafts Council Toronto conference gave her a sense of solidarity with others seeking to use “earth’s gifts”, such as natural dyes. And during her journey to Japan, she was deeply impressed with the close connection to nature in raku pottery.

“Sometimes she’d collect insects. And when she was going to do a firing she’d drop them in there, in the bottom of the pot, and the tiny minerals would seep into the glaze. And you’d get these tiny little impressions of butterflies in her pots.”

- Eileen Keys, Waterhole, circa 1970, stoneware with native copper and ash glaze, photo: Nalda Searles

- Eileen Keys, small bowl, rocks in the body, native copper with clear glaze, photo: Nalda Searles

Nalda was impressed with her criticality: “We went to a Gwyn Pigott exhibition at Fremantle Arts Centre. She was mates with Gwyn. She marches around and picks up a piece and says, ‘That’s too heavy, dear.’ out loud. Weight was really important to her. ‘It mustn’t fly out of your hand, and mustn’t weigh your hand down.’”

Stories like this reflect how Keys encouraged Nalda to take pleasure in her work: “When the kiln was ready, I would get a towel and take a bowl up to her room where she would put it bed with her. Even in her 80s, she would still get excited when something came out of the kiln. She would laugh. She’d squeal and be astounded.”

Towards the end, they diverged and Nalda became friends with the other major figure who shaped her art, Pantjiti Mary McLean.

- Pantjiti Mary McLean

- Nalda Searles

- Pantjiti Mary McLean

- Pantjiti Mary McLean

- Nalda Searles and Pantjiti Mary McLean

- Jimmy Donigan, Mollie, Elaine Lane and Mary McLean 2002, photo: Nalda Searles (sorry camp at Blackstone they asked her to take it

- Pantjiti Mary McLean

In 1991, during her final year at Curtin, Nalda was offered work in Kalgoorlie doing art workshops for “fringe dwellers”. Pantjiti Mary McLean would come in every day from Ninga Mia, a small Indigenous community outside town. Nalda had a system for making seed necklaces and was impressed with Pantjiti’s sense of colour and design. “We were drawn to each other.” Pantjiti invited Nalda home. It was her first experience of an Aboriginal dwelling. “There were milk tins for billy cans which appealed to me.” Her husband, a respected elder, lay on the bed in ill health in the single room.

Pantjiti’s paintings were selling well in a small gallery in Hannans Street. She was making dot paintings with a twig in yellow ochre, white, red and black. “I suggest that she try other things. We had paper. I started to call her ‘Pantjiti’. ‘Why don’t you do a man?’ ‘I don’t know man.’ ‘Just do a potato with legs on it.’ She made a circle with legs on it. That was all it took. She was off and running and you couldn’t stop her them.”

Nalda took Pantjiti to Fremantle Arts Centre, where the new exhibitions curator John Kean offered her a show in the Corridor Gallery, which was a “raging success”. Pantjiti stayed with Nalda. “She was a very good guest, always prowling around looking for things to paint on.” Nalda points to one of Pantjiti’s works in the corner of the room: “Underneath that is a painting of mine.”

Pantjiti’s career blossomed. She was taken up by Gabriel Pizzi and commissioned to make large paintings for Tandanya in Adelaide. They sometimes worked collaboratively on very large canvases: Nalda creating a base and Pantjiti painting over it.

In 1996, the two women went on a bush trip back to Pantjiti’s home country, Ngaanyatjarra lands. With their old dog in a beat up Hilux campervan, they drove thousands of kilometres visiting Pantjiti’s relatives in Cosmo, Warburton, Blackstone, Jamison, Kintore, Docker River, Mt Davies and then Uluru and return via Laverton to Kalgoorlie.

“She was a great walker. She laughed, ’You white fellas don’t know nothing. Get lost really easy. One fella out in Blackstone died because he didn’t know he could drink blood.’ She told endless stories about interactions with white fellas and poisoning. Two white fellas had done a lot of harm to the community. They were sitting in a gully, reading comics. Men crept up behind. Finished! A spear.”

In Blackstone, Nalda met the great Ngaanyatjarra fibre artist Kantjapayi Benson. “I heard someone call out ‘Kanjtaipayi’ This was the name Pantjiti had given Nalda, shared with a law woman. Mrs B is famous for conceiving Toyota Dreaming, which was made by the women of Blackstone and won the Telstra Art Prize in 2004. Nalda’s close connection with this fibre artist led to the Seven Sisters touring exhibition, toured by FORM.

Pantjiti was not interested in working with fibre, and left this to Nalda. It was during this time that Nalda participated in the NPY workshops organised by Thisbe Purich, which brought together needlecraft with fibre art and laid the basis for Tjanpi.

Pantjiti Mary McLean’s life is too epic to cover properly in this short article. Nalda remembers her recounting first meeting white people as a child. She worked as a drover in moleskins. She has touched many artists in Nalda’s circle. A Victorian Tapestry Workshop artwork based on her painting is now in the United Nations.

Like Keys, Pantjiti offered Nalda a critical structure, though this was cultural rather than modernist. “Pantjiti gave me wisdom and knowledge. Until you’ve had a close friendship with an Aboriginal person, you don’t really understand Australia… She didn’t like the big kangaroos I made, ‘cause that’s men’s business.’ She was so respectful of the protocols of her culture.”

It’s hard to leave Nalda without her voice ringing in your ears. I finally had a sense of how to connect the pieces together. Through Eileen Keys, we see how the European model of an artist as muse can be transplanted to the rocky landscape of Australia’s west. The seriousness of this vocation set up a framework for Nalda’s art. But it was Pantjiti Mary McLean who introduced her to the land, not as a romantic horizon, but as a living inhabited space.

It’s reassuring to know that Nalda did not come out of nowhere. She was shaped by two strong artists who followed their own laws. It’s a uniquely Australian story—one now continued by the next generation of artists who have developed their own languages of the land. They help a settler nation appreciate better the land it occupies, as understood by its custodians.

Author

Kevin Murray is managing editor of Garland. Since taking up the Writer in Residence program at the Meat Market Crafts Centre in 1990, he has been dedicated to advocating the value of studio craft to a broad audience through writing and curating.

Kevin Murray is managing editor of Garland. Since taking up the Writer in Residence program at the Meat Market Crafts Centre in 1990, he has been dedicated to advocating the value of studio craft to a broad audience through writing and curating.

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

Comments

Hello Kevin,,,,

we have a cabin in the woods in Nova Sciotia Canada,,,,when i discovered sweet grass and i started making sweet grass baskets in NS My journey of exploration took me to a book on Nalda from my daughter in Scotland,,,, Naldas work has been such an inspiration for me,,,

Now in Scotland,,with my daughter in Dunbar Ive been exoerimenting with sea weed ,,

I loved your above article ,,,Your descriptions of the artists work excite me! Thank you!!

How do I get a subscrition to Garland ? my website is http://www.barbaraguylong.com

Thanks Barbara. You may be interested in the article on wicker baskets that we have coming up in our next issue. We are also planning a Canada issue next year. We can put you on the artist list for notification if you like. Meanwhile, subscriptions are at http://www.garlandmag.com/subscribe. Your support is appreciated.

Thankyou Kevin for this insightful story. My husband and I met Mary back in 1992 when Nalda called in to our home to collect exhibition works from a show I had curated. Nalda and Mary were on their way to Fremantle Art Centre and stopped for a cuppa with us. It was wonderful to watch their friendship and collaborations blossom over the following years.

It was good to learn more about Nalda’s connection with Eileen Keys, a connection of which I was aware but not in any detail. I am surprised though that Marjorie Ridley’s name is not mentioned, as from my conversations with Nalda, Marjorie had a strong influence on Nalda’s use of local materials for her baskets. I believe Nalda has donated her substantial collection of Marjorie’s baskets and associated memorabilia to the museum in Bunbury near where Marjorie lived, and staff there are slowly collating this rich material.

Nalda was my teacher, Mary was a friend after that. Mary told me dreamtime story that were erotic, she was very cheeky with me. Nalda was very kind and gave me discipline. I will always remember our friendship.