It’s quite a combination. An austere black architectural Japanese form stands behind a pot in swirling blue and green nature-inspired designs. The tile below says Osaki Shigekatsu (1938-2005). What’s this Japanese grave doing in the middle of Uzbekistan? The answer to this question shows how connected Central Asia is to the East, centuries after the Silk Road.

The village of Rishtan in the Fergana Vallery is famous for its ceramics. The name Rishtan was formed from the ancient Sogdian word “Rosh”, meaning “red earth”, because of the reddish tone hoki surkh of the local clay. Today there are more than 1,000 hereditary masters, many of whom are sixth or seventh generation potters.

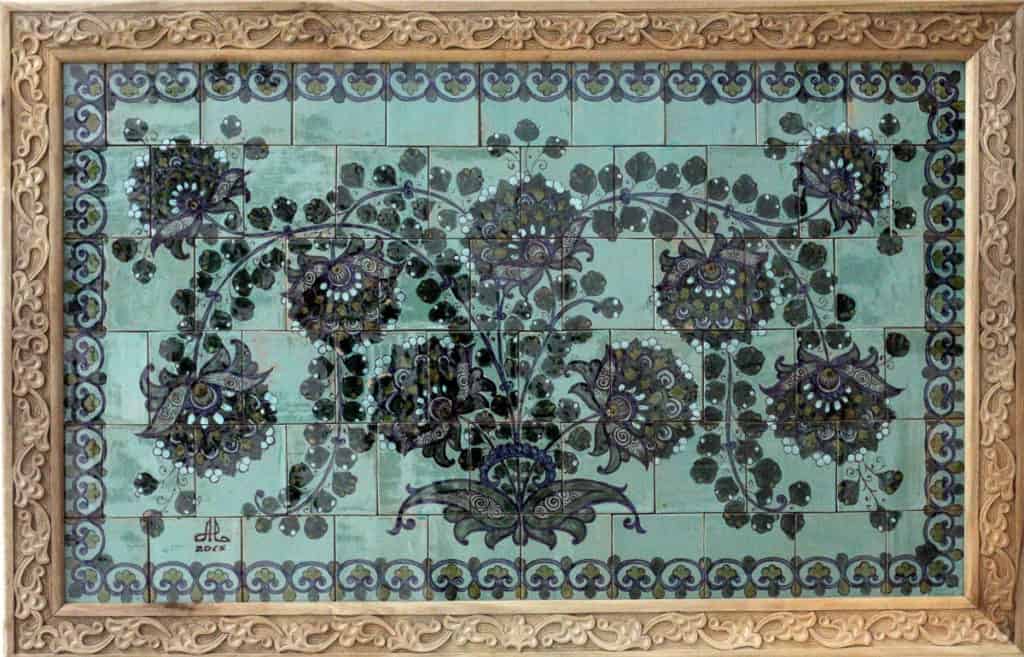

The glazes speak of the history of different civilisations that have left their mark in this valley. Blue comes from the fifteenth-century Timurid empire in Samarkand, while the Chinese celadon and snow-white painted cobalt porcelain comes from the Ming era around the same time.

This combination of four colours, “chor gul”, is particular to this region. They are all sourced from natural elements, such as cobalt for blue and iron for brown. With a keen eye towards archeology, Alisher sought to recover the ancient potash ishkor glaze, produced from a desert plant, which creates a light blue colour.

The workshop of Alishir Nazirov is known as “Usto-Shogird”. Nazirov has dedicated himself to reviving the ancient ishkor glaze that is obtained a plant called qyrq bogan, which has 40 branches. The tree is gathered from the desert and burnt. The glaze from this ash becomes like glass at 1400 degrees.

Nazirov was working in a ceramics factory in Rishtan which decided to try and sell its products to a Japanese market. He was commissioned for the task and spent one month in Kombutsu, where he studied under the ceramics professor, Asakura Isokichi-san. According to Nazirov, “He is a very famous master of the Kutani school of ceramics: its recognisable handwriting, subtle sense of colour and ornament. He was also interested in Uzbek, Rishtan ceramics.”

After his return to Rishtan, Japanese businessmen called Osaki Shigekatsu arrived in the village to set up a car factory for Daewoo. In 1997, knowing that Nazirov had a connection to Japan, they asked after him. Nazirov became friends with his wife who taught Japanese as a volunteer and they decided to open up a language school in his workshop. Meanwhile, Nazirov continued to visit Japan for sales and personal exhibitions in Komatsu (Ishikawa prefecture, Japan) in 1994 and 1996. He also took part in the World Ceramic Exhibition of Komatsu in 1997. In 2004 in Tokyo a personal exhibition was organised.

Nazirov was saddened by the death of Shigekatsu-san in 2005. “He was my friend. He worked as chief engineer at Komatsu and he really loved ceramics. When Japan began to cooperate with Uzbekistan, I helped him with the translation, since I know Japanese.”

He constructed this shrine out of respect for his friend. As with many Muslim shrines, it is based on a slight physical connection. In this case, a hair from the head of Shigekatsu-san was obtained to be buried on this site.

As far as we know, the historical Silk Road did not extend to Japan. But a friendship in craft knows no borders. Uzbekistan and Japan have both been enriched by this generous exchange of skills.

Comments

A wonderful story about connectedness. I have been to Japan several times and I am eternally grateful that I got to visit Uzbekistan just before the pandemic. Had wonderful experiences and encounters. I want to go back as soon as possible and visit the Fergana Valley which I felt I missed out on my last trip. Can’t wait to visit Rishtan. I am addicted to those colours.