In 2013 I was fortunate to visit Delhi for a three-month period to undertake research for a body of new work. I spent most of this time in Old Delhi, which is actually one of Delhi’s more recent incarnations and dates back to the 1600s when it was built by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan as the capital Shahjahanabad. I focused my research in an area around the Red Fort, Chandni Chowk and the neighbourhoods and laneways around Jama Masjid.

Today, a series of carved stone gateways that once formed a continuous wall around the city have become thoroughfares for the delivery of goods to what is now the city’s largest wholesale and retail market. The crumbling Havelis (mansions) of Mughal nobility function as warehouses, shops and offices for trade. Throughout Old Delhi’s neighbourhoods, the high architecture of Shahjahanabad interplays with the improvised awnings of street traders. It’s not much of a stretch to see the line of continuity between the canals and moon reflecting pools which once lined Chandni Chowk to the cheap Pineapple Chakri Balls that cast led sparkles and swirls of coloured light along Delhi’s most frequented and famous trading strip.

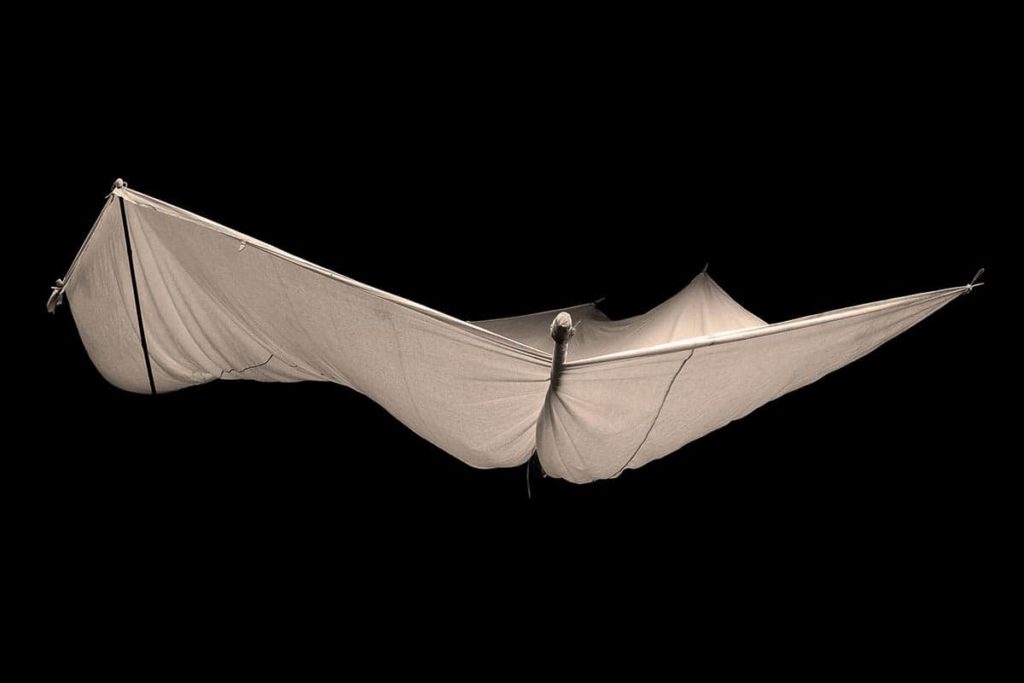

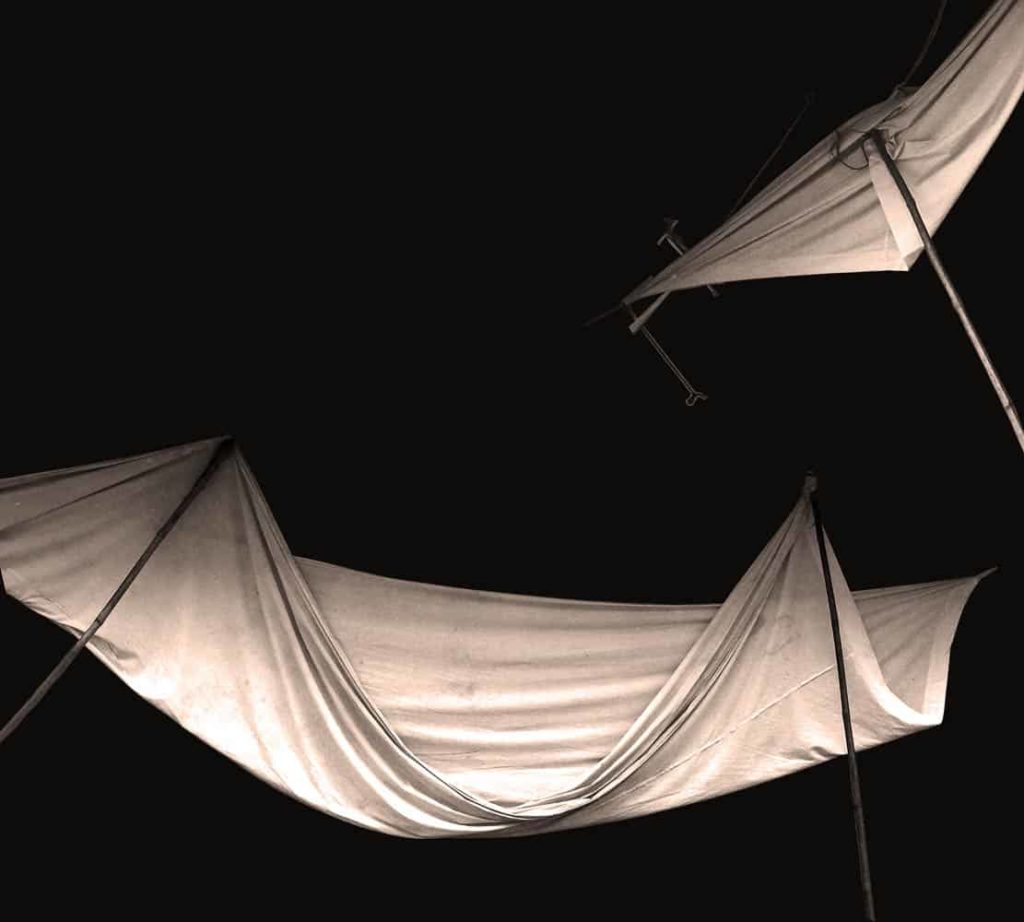

Time spent in Delhi culminated in my exhibition Chandni Chowk: One Altered Move at the Fremantle Arts Centre in 2015. The works in the show reference Mughal art and architecture, Islamic mythology, the use of tarpaulins by street side traders and Mondrian’s great ode to New York City, Broadway Boogie Woogie.

In this presentation for Garland, I have included my exhibition images, research photographs, Mughali drawings and maps and Andrew Varano’s exhibition text. I met with Andrew Varano for a series of studio visits, email conversations and sharing of research text and images. Andrew’s sensitive and expert handling of the great swathes of material that I provided him with and his subsequent text helps clarify and confirm the importance of the multiple threads and fragments that my research generated.

Alistair Rowe

Internet Browser Tab 1: Google Earth satellite terrain view of Old Delhi

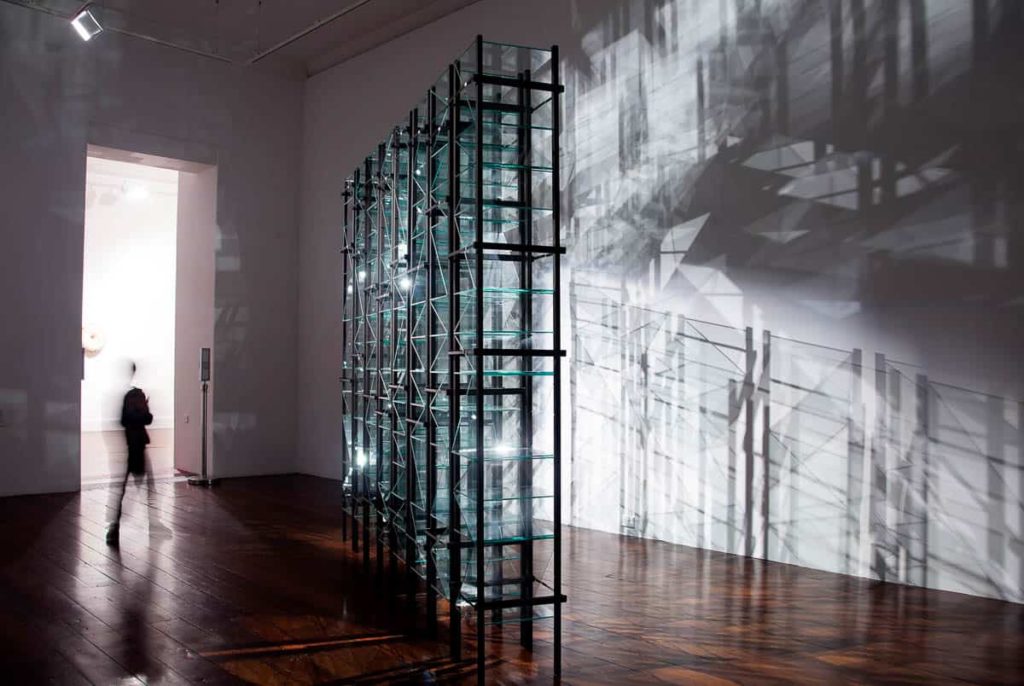

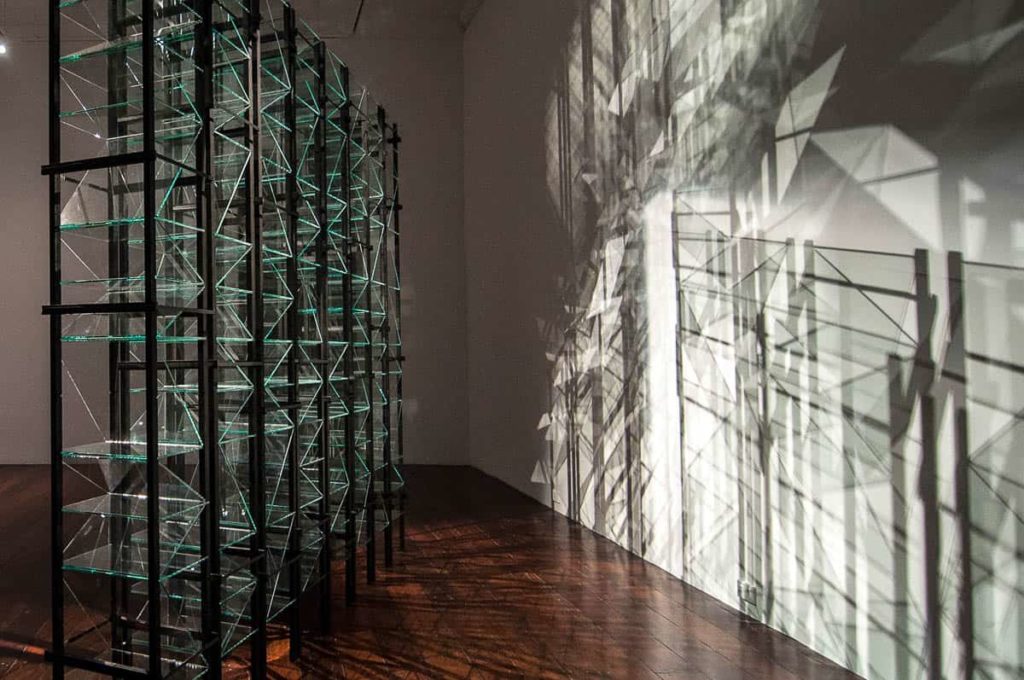

- Alistair Rowe, Chandni Chowk; One Altered Move, 2015, installation view, courtesy the artist.

- Jama Masjid, Delhi, courtesy the artist

Although I have never been there physically, on the internet I learn that orderly canals once flowed through the market of Chandni Chowk. Apparently crescent-shaped, their silky waters elegantly reflected the light of the moon giving the old market its name, which translates as Moonlight Square. Looking from a raven’s perspective, the power of omnipresence granted by Google Earth, Old Delhi is clearly defined by where the red brick and mud walls once stood. It sits just back from the Yamuna River, shaped like a quarter circle with the Mughal dynasty Red Fort installed like a hinge at its ninety-degree corner. A wide road juts out due west from the fort’s Lahori Gate, and branching out from this artery lies a densely woven network of commercial bustle. But from this flattened topological perspective—urban complexity muted by abstraction—the city seems a static geometric composition and becomes a series of angular junctions, channels and connections.

Internet Browser Tab 2: ‘How to See Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie’ by Michael Sciam

- Piet Mondrian, Broadway Boogie Woogie, 1942-43, oil on canvas, 127cm x 127cm

- Alistair Rowe, Chandni Chowk; One Altered Move, 2015, installation view(detail), courtesy the artist.

In the well-known essay How to See Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie, Michael Sciam picks apart in detail Mondrian’s homage to the city of New York, which Mondrian painted to celebrate both the city’s logical gridded urban planning and its lively jazz music scene. He begins by dissecting the painting functionally, assessing how different parts formally interact with one another. The tensions drawn between rectangles, the way our eyes are led by competing parallel and perpendicular lines and how colours “compenetrate” to create resonant fields and negative space are all meticulously explained. The thesis is that through applying this volley of techniques Mondrian created a composition both dynamic in its parts, but static in its overall whole. From here Sciam extrapolates this visual play as metaphysical enquiry, a Zen Koan posed in oils.

Internet Browser Tab 3: Technology of the Heart – The Prophet and Abu Bakr in a Cave / The Metaphysics of the Spider Web

- Jali, Humayun’s tomb, Delhi, image courtesy the artist

- Kalan Masjid Turkman Gate, Delhi, image courtesy the artist

- Alistair Rowe, Chandni Chowk; One Altered Move, 2015, installation view(detail), courtesy the artist.

Akbar remembered the story he was often told as a child of the benevolent spider who, ordered by Allah, wove its web across the entrance of a cave in which was hiding the Prophet and his father-in-law Abu Bakr. Their pursuers, seeing the unbroken web, were tricked into thinking that no one could have passed that way and so they abandoned their search. From inside the now-sacred cave, the Prophet and Abu Bakr looked at the outside world through the thin Jali of the spider web. The Prophet explained the ordering of the world to his friend, showing the hierarchy of all things in the concentric circles of the web, and the comparability of all things via the radii which joined them. It was shown that things could be distinct, but at the same time, a path could be drawn from any one point to any other. Because from any position a path could be traced to the deepest truth, the very central circle, then every intersection was also a place of divine presence.

From his window, the adolescent Akbar could see the nearby architecture of the Mughal Empire, a synthesis of Persian, Hindu and Timurid traditions mixed in brick and tile. Looking further into the distance he could imagine the architecture of the empire itself, picturing the movement of tributes drawn from the smallest village, through a network of increasingly larger trade posts, to eventually here in the capital city. Maybe this is what Akbar was idly observing when his father, Emperor Humayun, tripped and tumbled down the stairs of the library, spinning a radial line connecting his own reign to that of his young son.

Internet Browser Tab 4: Wikipedia page for ‘Indra’s Net’

- Laneway market tarps, Chandni Chowk, Delhi, image courtesy the artist

- Alistair Rowe Babur Juice Corner to Aurangzeb Metal Exports, 2015, archival inkjet print 100% Cotton Rag, 124cm x 93.5cm courtesy the artist

- Alistair Rowe, Chandni Chowk; One Altered Move, 2015, installation view(detail), courtesy the artist.

A fisherman’s net sits suspended in the air mid-cast. At every vertex of the net is placed a multifaceted diamond. In each diamond, the reflections of every other vertex can be seen, and within those, the same reflections are repeated again.

Internet Browser Tab 5: Google Street Views in parts of Old Delhi

- Mazar Ali Khan, Diwan-i-Khas, from the west, in 1840 – 44, British library

- Alistair Rowe, Untitled, 2015, digital print, 110cm x 99,cm courtesy the artist

Google Street View is an incomplete project within the walls of old Delhi, and you can only switch to a pedestrian’s perspective at a very few set points on the map. I’ve had the streets of Chandni Chowk described to me as chaotic and bustling, but a counterpoint is presented to me inside Divasa clothing boutique which appears completely depopulated. From even points within the store’s glossy interior I can see the neat crimson, emerald and saffron fabric stacks doubled back and forth within the internal reflections of the immaculate floor to ceiling mirrors.

From another Photo Sphere 400 metres flown in a straight line from the boutique—I fall outside Jama Masjid, The World-Reflecting Mosque, which from above appeared as a perfect diamond within a perfect square. With feet fixed at a precise point on the earth, I can spin in 360 degrees drawing an arc across the merchant stalls in this outdoor bazaar. This circle is dissected by ropes which pass above, drawing tight the tarpaulin coverings of the stalls. No one looks back at me, except for a young boy in a strange green and white chequered vest walking with a man whose legs are missing from the image, digitally amputated by an imperfect photo stitch which falls between him and the boy like an invisible metaphysical guillotine. The boy is captured between steps, his head is cocked towards the camera and his face squints in thought, unsure of what it is exactly that he is seeing.

Author

Andrew Varano is a curator and arts worker from Perth. Most recently, he curated the group exhibition ‘Remedial Works’ at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts where he was Acting Curator in 2016. He was previously a collaborator in the artist-run initiative Pet Projects (2016-2017) and a co-director of OK Gallery (2011-2013), both Perth based galleries.

Andrew Varano is a curator and arts worker from Perth. Most recently, he curated the group exhibition ‘Remedial Works’ at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts where he was Acting Curator in 2016. He was previously a collaborator in the artist-run initiative Pet Projects (2016-2017) and a co-director of OK Gallery (2011-2013), both Perth based galleries.