Vania Ruiz discovers a Chilean folk tradition that she uses to bring her father back into her life.

At a curve in the road, on the edge of the cliff, the roadside barrier opens, and a flat piece of land appears. In the center, there is this small animita, a house-like shrine, surrounded (and hidden) by a garden of natural and artificial flowers, fenced in white. Behind, a sign: “Elias Lookout, a gift from God. A son never dies.” On the sides, three benches and some pine trees frame the clear horizon. Below, the great Pacific Ocean and the small Laguna Verde village. Sunny afternoon, blue sea, gentle breeze, silence, peace.

It was spring, 2014. We arrived there with a model and a photographer, to make pictures of my jewelry series on Roadside Shrines, and the spot seemed perfect. But how to locate Elias family and ask for permission? Would they be upset or offended? All these things I wondered.

Suddenly, a car appeared and parked in front of the shrine. An older couple got out carrying a shovel, buckets, and other items. They were Elias’s parents.And so we talked. I told them why I was there for. I told them it all began with the memorial necklace Animita I made for my dad. I showed them the piece. They showed me all the anonymous presents and offerings the small shrine had received while tidying up the little garden. I learned that when the City Hall was building the new road, a roadside barrier had been installed blocking the access to the shrine, and how he managed to get the authorities to listen to him and open an entrance for them to visit their son. He then pulled an old newspaper out of the trunk. Two full pages recounted his feat. But I was also able to read how young Elias had jumped with his car off the cliff of Laguna Verde, one night in 2007.

“My son does good things for people,” his mother said, and then they showed me all the objects people had left as offerings. A cap, a handkerchief, a painting, some thank-you plaques, some solar lanterns for the night. “A Southern family even came to spend New Year with him… The benches and the pine trees planted around were brought by people coming to the shrine.This is how his animita grows…”

Baroque Art in Latin America

A year before, in 2013, I started my own path through art jewelry, thanks to a mentoring program we had organized at the Joya Brava Association, where we invited Rolando Báez, an art historian and expert in Latin American baroque art.

We studied aspects of this movement from a Spanish-Indigenous sacred art view, and delved into how this has had a subterranean influence on our culture to the present. Baroque painting in Latin America had an evangelizing purpose. Rather than looking to develop a technique, the intention was to transmit sacred stories to indigenous people who couldn’t read or speak Spanish. This led to the creation of a didactic art, where perspective and technique had no relevance. Only the message mattered. Nevertheless, the message grew, influenced by local culture, and so a new worldview, symbols and meanings aroused.

The Virgin of the Mountain (S Xvii, Potosí, Bolivia)

Virgin of the Mountain painting anonymous SXVII, https://newint.org/features/web-exclusive/2011/07/11/bolivia-mining-women-workers

For me, the most relevant example is the painting “The Virgin of the Mountain”, from anonymous author, probably indigenous, where the syncretism between Spaniards and indigenous populations is evident. It fuses the image of Virgin Mary with the Pacha Mama (Mother Earth), represented by the hill of Potosí, Bolivia, as one same entity.

If we look at the painting, we can “read” a whole story: the Virgin-Hill being crowned by The Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit (the dove) in a heavenly sky above the clouds. In the lower front, King and Queen of Spain. In the background, the Inca gods Sun and Moon, and Inca King also witness the ceremony.

Pagan Roadside Shrines

One day by chance, I happened to attend a talk by a company that offered roadside shrine tours. The roads in Chile are full of them from North to South. No one dares to take one down. They are sacred, but also feared.

Soon after I made the connection. Roadside shrines are also a form of syncretism between indigenous animism and the Catholic religion, and to this day, they continue to be built throughout the country, to remember a tragic death. Even though animitas are all different, they have considerable similarities with Latin American baroque art. These small pagan house-like shrines built with humble materials, describe, through the objects placed inside, the lives of those who died. They tell a story. Some have a particular meaning and others a universal one. Fake flowers for eternity. Fire, wind, water and air, also present through candles and bottles. Animism meets Catholicism.

In Andean animistic culture, it was believed that the soul was smaller than the body. Hence, the size of these little houses built to help wandering souls, from a tragic death, find their way to the other world.Although built originally by family and friends, they can become devotional milestones over time. Prayers and offerings are part of the accompanying ritual. Thus, when a roadside shrine grants favors, it fills with offerings and grows beyond the house. It becomes successful, remembered and sanctified (in a pagan way).

Regardless of who the deceased person was in life, the only requirement to have a roadside shrine is dying tragically and someone willing to build it.

Revelations

At that moment, everything made sense.

My father drowned in 1991, at the age of 39, while rescuing a teenager in a lagoon. My project would then be to build a wearable animita for him. So my mom and I collected old pictures, letters, and all kinds of souvenirs from him.

Process

- Vania Ruiz, Animita Ayudame Papito, 2013, copper fabric paper resin twigs merquen, 30cmw 35cmh 3cmd; photo: Maria Cirano

- Vania Ruiz, Animita Ayudame Papito, 2013, material copper fabric paper resin twigs merquen, 30cmw 35cmh 3cmd; photo: Maria Cirano

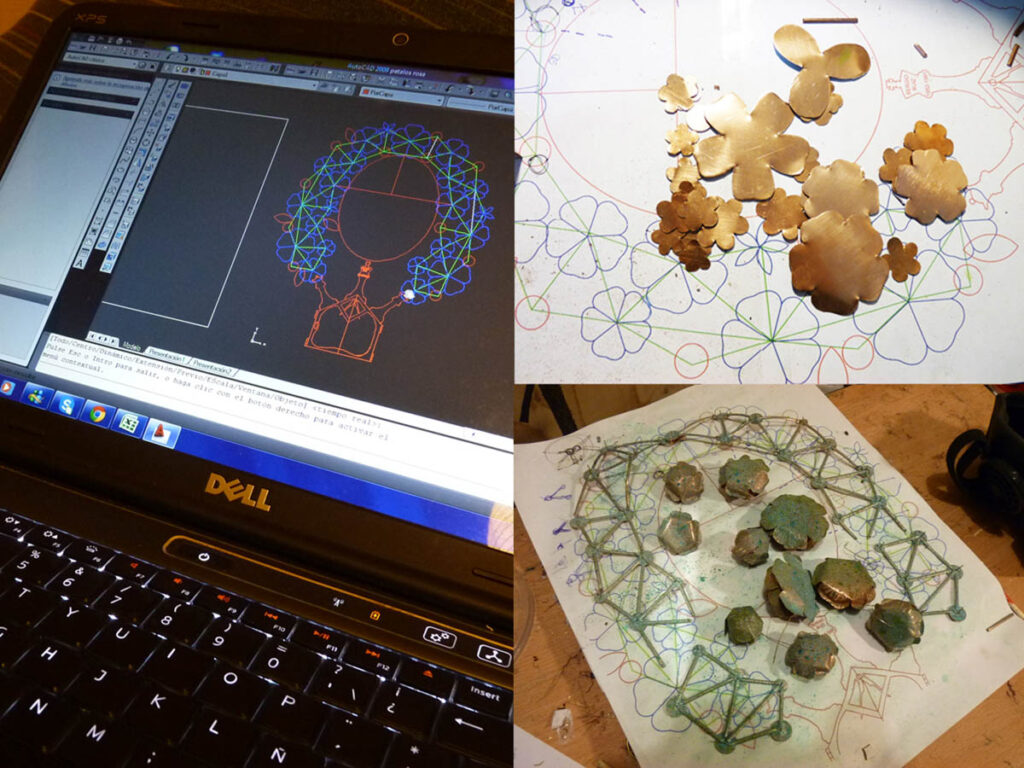

- Animita design process, 2013; photo Vania Ruiz

My dad was a bright mathematician, and he studied graphs. He was always connecting dots and lines on a napkin. He was a chess player, a Masonic Lodge member, an atheist, a charming cheerful ladies’ man, an alcohol enthusiast and workaholic who liked travelling, gambling and whose favorite flowers were red roses. A childish, adorable self-centered hedonist. Drowned in a lagoon while saving the life of another.

The small shrine house has a chess king instead of a cross and is surrounded by queens. The doors made with curahuilla landscapes makes a wink to his fondness for alcohol. They also carry the symbol of the Masonic Lodge.

Inside I placed his picture surrounded by paper flowers and a personal message stamped on a little frame. On the reverse, I stamped “Help me Daddy”.

The garland of roses and flowers was placed on a graph of dots and lines that would form the links of the necklace.

The entire piece is made of copper. I chose this material because it resembled rusty metal and timing, and because it is characteristic from Chile.

His animita hangs now on my living room wall. But it has travelled to many places in the past. I like to think he still enjoys planes and social life.

A small roadside shrine, to have you with me.“Help me Daddy”

- Vania Ruiz, Animita Ayudame Papito Neckpiece 2013: photo: Pilar Castro

- Vania Ruiz, Animita Ayudame Papito, 2013, copper fabric paper resin twigs merquen, 30cmw 35cmh 3cmd; photo: Maria Cirano

Further Reading

Plath Oreste (1993) L animita : hagiografía folklórica. Chile. P&P Ediorial

Forch Juan (2003) Animitas Templos de Chile. Chile. Cuarto Propio

Ojeda Lautaro, Torres Miguel (2012) Animitas. Deseos cristalizados de un duelo inacabado.

About Vania Ruiz

I’m a Chilean architect and jewel designer based in Viña del Mar, Chile. I’ve always had a need to make things by hand, and started making jewelry in 2009. Since then, I divide my time between my jewelry Brand Casa Kiro Joyas, my artwork as Vania Ruiz and my family. Jewelry has been a gift because I get to do the things I like the most: making and telling stories. In my work, I seek to understand and celebrate our culture, from a feminine perspective. Visit www.casakiro.cl and follow @casakiro.

I’m a Chilean architect and jewel designer based in Viña del Mar, Chile. I’ve always had a need to make things by hand, and started making jewelry in 2009. Since then, I divide my time between my jewelry Brand Casa Kiro Joyas, my artwork as Vania Ruiz and my family. Jewelry has been a gift because I get to do the things I like the most: making and telling stories. In my work, I seek to understand and celebrate our culture, from a feminine perspective. Visit www.casakiro.cl and follow @casakiro.

Comments

Vania, thanks for sharing. As a foreigner living in Mexico, I can understand the need to create an Animita a small shrine to the lost but always remembered. Although the day of the dead has become somewhat commercial it´s still a widely practiced custom and a dignified way to remember those of the past.