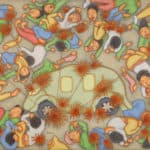

- I Dewa Putu Mokoh, Bom Bali, 2006, Chinese ink and acrylic on canvas, 63 x 82cm (framed) Charles Darwin University Art Collection CDU2993.

- Julie Dowling, Warridah Melburra Ngupi, 2004, acrylic and red ochre on canvas, 150 x 120 cm, Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, The University of Western Australia, CCWA 777.

- Anonymous artist associated with Big John Dodo, Untitled, undated, carved stone with paint, dimensions unknown, Collection of Dan and Diane Mossenson.

- Wendelien van Oldenborgh, No False Echoes (video still), 2008, video installation, 30mins, courtesy of the Artists and Wilfried Lentz Rotterdam.

- Tom Nicholson, Indefinite Distribution (After Dili Action), 1999-2010, detail of installation, Type-C photograph, 57.4 by 76 cm, courtesy the Artist and Milani Gallery

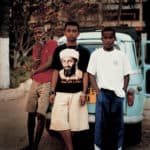

- Max Pam, detail from Reporting Madagascar, June/July 2003, 80 scanned pages from artist’s handmade journal printed on Canson Infinity Edition Etching Paper, 30 by 27 cm each, courtesy of the Artist.

- Rodney Glick, Everyone No. 177, 2012, carved and painted wood, 120 by 160 by 60 cms, courtesy Murdoch University Collection

- pvi collective, documentation of transformer performance, 2016, colour photograph with oversized playing card, dimensions unknown, courtesy of the Artists, photo: Lihlumelo Toyana

- Tony Nathan, Untitled, from Kawah Ijen series, 2011, photograph, 900 x 600mm, Courtesy of the Artist.

- Punkasila, Kristiantoro Seri Punkasila (KSP), 2006, handmade mahogany guitar, batik-lined embossed case, mechanized tripod, dimensions variable, courtesy of the Artists and Darren Knight Gallery.

In 2013 I curated In Confidence: Reorientations in Recent Art for the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts after having spent several months in London researching the relationships between the international art market and major institutions. The exhibition had its origin in a presentation I gave at There is No Global, a small conference I convened at a college in Bloomsbury towards the end of my stay, to which I invited a number of Australian artists and writers then also based in London, among them the artists Paul Knight and Christian Thompson.

At that point in time Australia, especially Western Australia, was in the throes of the “mining investment boom”, so I, with my long-standing interest in the Indian Ocean region, proposed that it would be an opportune moment to think about how the Australian art scene could connect with the larger South-East Asian and Indian Ocean art scenes.

In my talk I showed works by a number of artists who I thought would be striking examples of the possibility of this kind of international practice: among others, Hossein and Angela Valamanesh, Danius Kesminas with the collective Punkasila, and the Bali-based sculptor Rodney Glick. Although the audience seemed indifferent to the intended art-market and political dimensions of the conference, there was strong interest in the works and in their surprisingly natural hybridity. One of the invited writers suggested it would make a good show.

For an exhibition of its scale, In Confidence was developed very quickly, drawing on not only some of the artists I had discussed at the conference, but also on artists with whom I have worked with before or whose practices I have admired over the years: Simryn Gill, Tom Nicholson and Max Pam, and also lesser known artists, Australian and Asian. We exhibited video and photographic works by Christian Thomson, a series by the Kimberley painter Lisa Uhl, a major South-East Asian video work by the Malaysian Hayati Moktar, and the UK-based Singaporean Lynn Lu was represented by video documentation and also created a new performance. The Yogyakarta-based collective Punkasila, with its initiator Danius Kesminas, showed their collaborative paintings, their functional – as instruments! – machine-gun guitars and a selection of their raw, exciting music videos.

With the aim of articulating an appropriate context for the show we organised the conference The Ambiguity of Our Geography. My opening address drew on an essay I had written about a decade before for the catalogue of an exhibition of Australian art that would tour Asia. The essay didn’t appear there, instead having an interesting afterlife thanks to the Melbourne literary journal Meanjin.

Titled “Australia is not an Island”, the essay was written in an ironic mode, one unfamiliar, it seems, in the art context. Its purpose was to lightly parody Australia’s infamous “tyranny of distance”, that is Australia’s distance from Britain and the US. In it I suggest that Australia is not a landmass, not a continent, not even an island, but actually a collection of islands, an archipelago. If the cities of Australia are seen as islands in an archipelago, it would be clear that certain island-cities have closer relations to the island-cities of other countries than they do to cities in their own country. For example, Perth is often said to be closer to Singapore than it is to Adelaide (which is untrue); yet it is a shorter flight to Denpasar than to Adelaide (though Bali is actually further away). There are the distorted proximities of air travel, just as there are those of culture. It was intended ironically and seriously. After all, New York, the capital of global art, is said to be an island off the coast of the US…

While the trope of the opening address was self-evident, its larger implications, the ambiguity of cultural geography itself, was too elusive, perhaps too ambiguous, for the ensuing discussion. In truth, the theme of the island and the coast was present throughout the show, whether in Nicholson’s East Timor work, Pam’s project on Madagascar, Moktar’s video-work, and, most notably, in Gill’s Run (2006), a work which documents her visits to the island of the same name, the island which was exchanged by the Dutch – for the island of Manhattan no less – as part of a package at the end of the Anglo-Dutch War of 1665-67.

Although Australia is still often regarded as disconnected from the wider-world, especially if that wider world is poor, I was hoping that the notion of geographical ambiguity could also be seen in reverse, as an alternative hallucination. I was hoping that Perth, a city in which the office-towers of multinationals largely backed by US capital, Rio Tinto, BHPbilliton and Chevron, not to mention the big four Australian banks, could be seen as a bad kind of mirage, an illusion which would be corrected by looking for another lived reality, a more local, more geographically and politically sensitive reality. Australia’s only, and lonely, Indian Ocean city, I imagined, could then be seen as merely one of many culturally-rich, tropical islands in a large, spreading Indic archipelago.

Perhaps this was too hopeful, as globalisation is for the Anglosphere largely Americanisation, and Australian culture has been successfully americanising since the 50s. But if it is true that this kind of past and current self-colonisation has blinded us to the disturbing realities of the present, then it may be equally true that the peculiar relationship that many Australians have to Britain has occulted a range of current cultural realities.

It may actually be the case that, in a structural sense, Australia has more in common with Singapore and South Africa, and indeed with the UK itself, than it has with the US.

My reflections on the disjunction between overarching political or imperial realities and the experience of life on the Indian Ocean edge of the Australia continent, led me to wonder whether we might be better occupied imagining another, earlier, colonial and global possibility.

The resulting exhibition in 2016 was Invisible Genres for Perth’s John Curtin Gallery, a large scale exhibition of contemporary art from Australia, the Netherlands, South Africa and Indonesia. Intended to commemorate the 400th year since the landing of the Dutch explorer Dirk Hartog on the coast of north-western Australia, I chose to select work by artists from several of the countries that the Hartog voyage touched on, each of them having important relations, both past and present, with Australia.

Instead of making of Invisible Genres the kind of show that is typically prepared for countries celebrating the anniversaries of their multilateralism, exhibitions that pair like-with-like, I undertook research into the visual culture of Hartog’s time in an effort to see if I could develop a curatorial method for the show that would free it from the various nationalisms and from any tendency to a conventional and art historical overview. Instead of a British orientation, it would be, ironically, Nederlandish.

My discovery that the Netherlands and much of northern Europe had been wracked by iconoclastic riots preceding the Reformation, and that one of the consequences was the flourishing of what we would now regard as the origins of the international art-market, led me to take that period of iconoclasm, its on-going ramifications, as the point of origin for and concept of the show.

Research revealed that it was during the decades following the Reformation that the commercialisation of art encouraged the flourishing of the now familiar genres of art. This was largely because artists were reluctant to risk working on the religious and historical themes for fear of persecution. The book accompanying the show, Invisible Genres: Two Essays on Iconoclasm, includes essays by myself and the Dutch art historian Arvi Wattel, and there we describe these issues in detail.

Following on from my curating In Confidence, during which I had been intrigued to find the persistence of the traditional practices of landscape and portraiture in much contemporary work, I decided to utilise the four principal genres of painting (portraiture, landscape/seascape, still-life and “genre”, or the everyday) that became popular during the period following the iconoclasm and Reformation, the Dutch “Golden Age”, as a schema according to which I would select the works by the contemporary artists.

Although at least one art historian has objected to this, I still feel that this – albeit ironically historical – strategy may give insights that conventional histories are not able to, that it allows several, simultaneous possibilities: we can ignore the categories and histories of current art, ie. photography, painting, conceptualism, and their trajectories; we can look for commonalities of practice beyond national boundaries; and, also, we can see work in relation to that under-investigated and literally revolutionary moment of iconoclasm, that period during which “blankness” was introduced as an important element of the Western tradition. In a way, it could be argued that by emptying the churches of art, the Reformation not only encouraged the potential of abstraction, it also, unwittingly, created contemporary art’s gallery space, the ubiquitous “white cube”.

Invisible Genres was developed around a central gallery containing Wendelien van Oldenborg’s No False Echoes (2008), Abdul-rahman Abdullah’s Al Falaq (2013) and the Balinese I Dewa Putu Mokoh’s painting Bom Bali (2006), all works related to spiritual experience. This was to retain the conceptual and spatial centrality of the question of religion in the structure of the show. Although each work represented a religion, Mokoh’s unusual work, a painting of the 2002 bombing of the Sari Club in Kuta, Bali, depicts the scene of the terrorist act while subtly alluding to the subsequent purification rituals that were used to overcome the trauma of the event. As part of the exhibition’s public program we screened John Darling’s documentary The Healing of Bali (2003), which gave further context to Mokoh’s work.

The show also drew on previously unseen art and on major works of the past decade, including works by the South Africans William Kentridge and Candice Brietz, and the Australians Jacqueline Ball, Gregory Pryor, Tony Nathan, Julie Dowling and the performance ensemble PVI collective.

Included, too, was a body of work by the Kimberley sculptor Big John Dodo and several of almost forgotten artists associated with him. In the course of my research I had found in a private collection what amounted to a cache of more than eighty works. These works were especially interesting in that they prompted a series of questions about the nature of art-making that are unique to Australia; illuminating the evolution of a practice from Indigenous spiritual context, through commercialisation, and then on to have the status of artworks. This would be the first time in over two decades that they had been exhibited together as a group. I discuss this in my essay, “Invisible Genres, or On the Virtual and the Actual”, in the book documenting the show.

While each of the works were chosen for their conforming, whether immediately apparent or not, to the scheme of the genres, van Oldenborgh’s No False Echoes was literally central in the gallery spaces and was the core of and conceptual key to the entire show. A work about the Dutch memory of colonial Indonesia, much of its action takes place in a defunct building which belonged to the government agency that produced radio programs for broadcast to the Dutch East Indies. The work is complex, in many ways resonant. Yet what was immediately striking was the way the building itself evoked the post-Reformation churches of Golden Age Holland, those churches that had been violently emptied of their visual art.

By taking the “blankness” of that space, of the building van Oldenborgh filmed and as a concept, I hoped to prompt the viewers of the show to reflect on how that kind of blankness might have actually prepared the Dutch to see, years before the British arrival, their own kind of vacancy, their own “terra nullius”, on arriving in Australia. The works by the other artists in the exhibition were to be viewed in relation to that particular visual, historical blankness. Each work became in effect its own attempt to overcome the iconoclastic violence of colonisation.

Throughout the show the interplay between the experience of visibility and invisibility made apparent the politics of borders, something especially relevant when it is remembered that even today the asylum-seekers who arrive by boat in Australia’s north-west have largely followed the ancient Arab, Indian and South-East Asian trade routes that that predate European arrival, both Dutch and British, by as much as half a millennium, a history that, like that of indigenous Australians, has also been forcibly erased.

Reflecting on those two exhibitions, on six years of curatorial work, after twenty years of writing criticism with a similar ambition, I am wondering whether it is after all feasible to create a cultural awareness of the Indian Ocean region here in Australia, here in a city on the Indian Ocean coast, in a place where the audience, due to their own personal histories, should be receptive. Three interesting recent projects, Another Antipodes: Urban Axis, curated by Gerald Sanyangore, Valerie Kabov and Roelof Petrus van Wyk, and I Don’t Want to Be There When it Happens, curated by Mikala Tai, Kate Warren and Eugenio Viola, exhibitions of contemporary African art and Pakistani art, along with the High Tide biennale directed by the sculptor Tom Muller in Fremantle have indicated that a broad and large audience interested in these questions may be in the making, so there may be the case to be hopeful.

Even Australian government officials have quite recently started using the term “Indo-Pacific”, instead of “Asia-Pacific”, to describe the region. It seems to be an attempt to distance the government from its previous role in Asia where it was seen as an agent of larger powers, a role that is now more complex with China interrupting the existing archipelagos of eastern Asia by building its own small, militarised islands in their attempt to redraw the map of the region. The existence of their islands isn’t, in fact, ironic…

But a change in terminology, or even the redrawing of new maps thanks to the American “pivot to Asia” and China’s artificial islands, is much easier than changing our vision of the Indian Ocean region to one that can allow us to see wonderful, connected islands – an archipelago of the decolonized mind.

Author

John Mateer is curator and writer. For more than two decades he has written art-criticism. In recent years he has curated the exhibitions, In Confidence: Reorientations in Recent Art and Invisible Genres. Among his other projects is The Quiet Slave for the Australian biennale Spaced2: Future Recall, a project which recovered the history the Malays of the Cocos-Keeling Islands, about which he has given talks at various European institutions and at the School of African and Oriental Studies in London. He has also been a visiting lecturer at Maumaus, an independent art school in Lisbon.

John Mateer is curator and writer. For more than two decades he has written art-criticism. In recent years he has curated the exhibitions, In Confidence: Reorientations in Recent Art and Invisible Genres. Among his other projects is The Quiet Slave for the Australian biennale Spaced2: Future Recall, a project which recovered the history the Malays of the Cocos-Keeling Islands, about which he has given talks at various European institutions and at the School of African and Oriental Studies in London. He has also been a visiting lecturer at Maumaus, an independent art school in Lisbon.