Pamela See considers whether the decorative layer constructed through augmented reality might be considered a new craft.

Over the past decade, augmented reality (AR) has developed from a disruptive technology to a medium that is celebrated by art aficionados around the world. Although the technology emerged during the 1960s, it took thirty years to find industry application and a half-century to become available for domestic use. What began as a method of assisting in aircraft maintenance and medical treatment during the 1990s, was employed as interventionist art during the 2010s. Chinese artists critiquing their own government were amongst the most prominent. Nonetheless, a decade onwards two of China’s key art institutions staged significant showcases in AR.

AR art has a development that mirrors the trajectory of Surrealism from a form of political resistance in France, led by Andre Breton, to a popular genre in the United States, exemplified by Salvador Dali. However, the transition of AR from digital squatting in cultural centres and events to a legitimate art form has continued to evolve. In its most recent iteration, AR has been driven by public program departments within the gallery sector as opposed to visual artists. The educators foresaw the potential of using AR to interact with visitors prior to the advent of COVID-19.

In this new epoch of social distancing, when touch is at a premium, AR presents an alternative to interactive craft stations for children. However, what are the ramifications for both the audience as end-users and practitioners as subcontractors? Is AR the new craft and is swiping of handheld devices the new touch? How does this transition affect AR as a legitimate artform?

What is AR and where did it come from?

AR, as opposed to virtual reality, involves the overlaying digital elements onto physical reality, which is in most cases filtered through handheld devices such as smartphones, wearables or smart screens. Alternative forms of AR include virtual mirrors, desktop displays and projected displays.

AR was devised in 1968 by the inventor of both integrated graphics and the first computer-aided design program Sketchpad, Ivan Sutherland. His AR device, The Swords of Damocles, transposed a wireframe room onto an eyepiece. The head position was tracked, enabling the wearer to adjust their vantage point in real-time.

Contemporary AR apps are differentiated not only by their method of display, but also by how they register, track and calibrate. In 2020, there were ninety-three startups using AR in China alone. Three of the most common technologies presently employed by AR apps are locative/global positioning system (GPS), environmental/spatial recognition and planar recognition. A variation of the latter, fiducial, emerged during the 1990s, and was built on contour-based shape detection that originates from the 1960s.

The term “augmented reality” was coined by Thomas Caudell and David Mizell in 1992. The pair of scientists were creating instruction manuals for Boeing. In the proceeding decade medical applications for AR began to emerge from the University of North Carolina. AR has since developed to assist in the diagnosis of illness, the training of medical professionals and the planning for complex surgical procedures.

AR: The art of intervention

Shortly after the release of smartphones by Apple in 2007, artists and activists began employing the technology. The first significant intervention into a museum or gallery space was instigated by Sander Veenhof and Mark Skwarek in 2010. Endorsed by the festival Conflux, DIY Day was staged on 9 October and occupied the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) with a GPS coordinated exhibition. Manifest AR, the international cyberart group of which the two aforementioned artists are a part, also created their own unauthorized “pavilion” at Venice Biennale in 2011. The artworks were reinstalled in the Istanbul Biennale later in the same year by invitation of one of the curators, Lafranco Aceti.

Amongst the contributors to Manifest AR are 4Gentlemen. The collective working under the pseudonym includes Professor John Craig Freeman from Emerson College, and Chinese artists Lily Yang and Hong Lei Li. The title makes reference to Four Gentlemen, one of whom was Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Liu Xiaobo, who played a role in organizing the ill-fated Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. The art collective used AR to “…allow Tank Man’s spirit to return to Beijing and stalk his former haunts.” In 2010, Tiananamen SquARed was staged using GPS in the precise location of the historical event it represented. The installation was also transposed onto a number of other sites, including the aforementioned Venice Biennale.

Yang and Li explored similar subject matter in their papercut animation Forbidden City, which received the People’s Choice Award at the Moving Paper Film Festival staged at the Museum of Art and Design in 2009. Papercuts have been affiliated with divination from their first historical accounts during the Western Han Dynasty (206BCE – 24CE). A papercut likeness, fashioned from hemp, was used to summon the presence of Lady Li, a favoured concubine of Emperor Wu. He was a devout follower of the Yellow Thearch, a cult of immortality. Papercuts, as talismanic figures without ground, were used to communicate with the immaterial world. Subsequently, the transition from papercut animation into AR appears to be a natural progression for the collaborative.

The eruptions of the immaterial that AR entails matches a number of the key attributes of the Surrealist movement, including the uncanny, juxtaposition and autonomism. The latter employed the irrational to subvert the rising authoritarianism that dominated the interwar period. The limited field of vision offered by AR devices is not unlike the canvases of surrealist paintings that offer a window into the mind. The abstraction of Chinese landscape painting, which was catalysed by the literati during the Yuan Dynasty (1271 – 1368), similarly focused on depicting internal realities in response to a Mongol occupation. AR interventions provide the opportunity for a collective liberation of consciousness, unadulterated by governments or corporations.

It is, perhaps, unsurprising that the benchmark for the democratisation of the medium was initially banned by the Chinese government on the grounds of imposing a security risk. Pokémon GO was released elsewhere 6 July 2016, with the downloads of the application reaching five hundred million in the first forty-three days. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) encouraged the development of “indigenous” providers of AR. Both Alibaba and Tencent released AR applications in 2017. Concern over the sovereignty of their geo-digital borders was not an exclusive concern of PRC. In late 2019, a class-action against the developers of Pokémon GO reached a settlement. The developers of the app paid four million US dollars for “virtual trespassing.” The plaintiffs were primarily owners of residential properties.

AR: The craft of public engagement

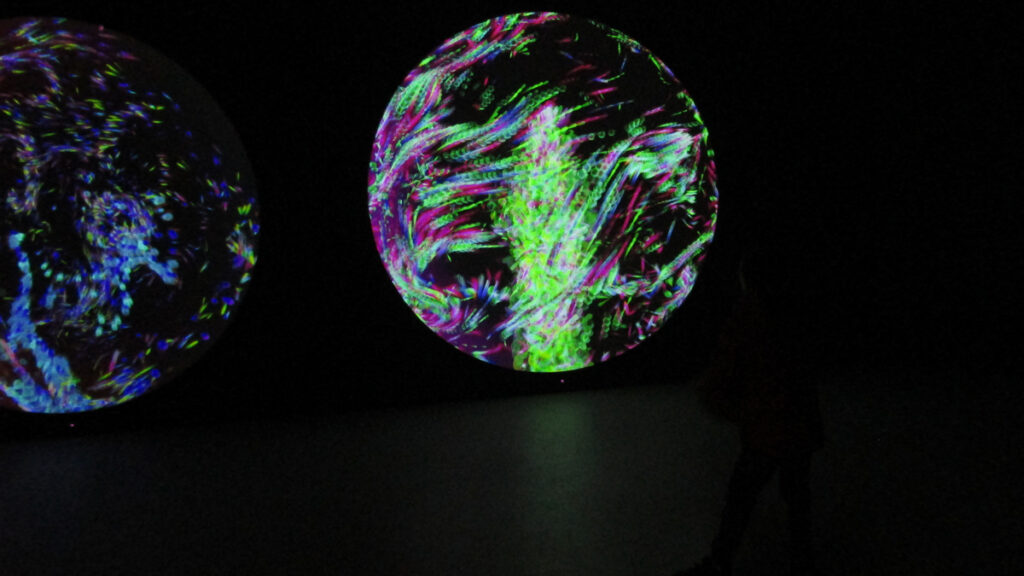

In late 2019, the Meixihu International Cultural and Art Centre (MICA) opened at Changsha with Flowing Eternity by MOTSE 墨子. Comprising forty artists and scientists, the Chinese collective filled the Zaha Hadid designed building with an equally formidable showcase of new media art. The digital elements were overlaid using projection as opposed to employing handheld devices. The AR artworks ranged from virtual mirrors, which tracked and responded to the movement of visitors, to 3d printed buildings with fiducial AR. The overlaying projected animation enabled the cityscape to evolve. Partner of the architectural firm, Patrik Schumarcher, described in his manifesto Parametricism as Style their application of a “continuous differentiation” to “advance the design of integrated, immersive worlds…” Through AR, MOSTE applied this principle to the visitors of the centre.

Examples of virtual mirrors created by scanning the movements of viewers at Flowing Eternity by MOSTE at MICA in Changsha in 2020; photo: Pamela See

This integration of visitors was taken further through a collaboration between the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) in Beijing and the British AR company Acute Art. The exhibition Mirage: Contemporary Art in Augmented Reality opened in late 2020. It featured a series of 3d modelled vignettes for visitors to encounter using their mobile phones. The theme resonated in the titles of a number of the artworks including Olafur Eliasson’s Solar Friend, Nina Chanel Abney’s Imaginary Friend and KAW’s Companion. In The Eternal Wave AR: Li Nova by Cao Fei, one child is depicted in the corner with a desk and multiple floating pets: the virtual boy attempts to engage its human counterparts. The advent of COVID-19 adds poignance to these explorations into companionship.

The uptake of AR by the museum and gallery sector was already increasing exponentially prior to the advent of the pandemic. In 2013, Vladimir Geoimenko exhibited a series of AR paintings at the Scott Building in Plymouth University in the United Kingdom. The Boston Cyberarts Gallery staged a showcase of a number of AR art pioneers, including Manifest AR’s John Craig Freeman, in 2016. Whereas the aforementioned exhibitions showcased AR artworks, the augmentation of existing artworks facilitated by public program teams in museums and galleries is also becoming increasingly common. AR practitioners are being employed to create opportunities for audience interaction.

In 2017, The Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto engaged Alex Mayhew, a local digital artist and co-founder of the creative technology company Impossible Things, to augment paintings from their collection. In ReBlink, the compositions which triggered Mayhew’s 3d animations were from movements such as Baroque and British Realism. Over the duration of the exhibition the average time spent by visitors in the gallery increased from four to nine minutes. Eighty-six percent of visitors also reported feeling engaged by the artwork and thirty-nine percent looked at the painting again after utilising AR. A similar approach was adopted by The Art Gallery of New South Wales in their 2019-2020 exhibition Japan Supernatural. Australian “digital storyteller” Helena Papageorgiou augmented a mural by Sydney based illustrator and artist Kentaro Yoshida. Although this collaboration was enjoyed by children, the augmentation of another Australian exhibition explicitly used AR to engage younger viewers in late 2020 – early 2021.

Collaboration between Kentaro Yoshida and Helena Pagageorgiou at Japan Supernatural at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2020; photo: Pamela See

miffy and friends at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) Art Museum primarily focused on the artwork of Dutch illustrator Dick Bruna. In the past, like many other museums and galleries within Australia, it used craft to facilitate interaction for younger audiences. However, on this occasion, a number of the paintings were enhanced using AR by Visual Communications Lecturer Dr Anastasia Tyurina.

Lending a material hand

Although the two aforementioned practitioners have exhibited in international forums, neither of their contributions was celebrated by the affiliated art institutions. In late 2019, Pagageorgiou contributed to the AR component of the 5th Ranetas VR Fest in Spain. Tyurina similarly contributed towards the Artech 2019 Exhibition for “Art, Ecosystem and Digital Media” in Portugal. However, their roles in these Australian initiatives appear to be treated as, literally, immaterial.

Can their meticulous interpretations of paintings into interactive augmented animations be categorised as craft?

Can their meticulous interpretations of paintings into interactive augmented animations be categorised as craft? The authorship, or more precisely creative authority, remained with Yoshida in the collaboration with Pagageorgiou. Equally, the integrity of Bruna’s compositions was respected by Tyurina. Her augmentations resembled the movable book versions of his work. Yet, what makes this interpretation of craft unique is that the “Greater Arts” component has been assigned to the material element. In 1882, William Morris, the founding father of the Arts and Crafts Movement, wrote:

All the greater arts appeal directly to that intricate combination of intuitive perceptions, feelings, experience, and memory which is called imagination.

Materiality was inextricable from the late eighteenth and nineteenth-century elevation of the “Lesser Arts” in Europe and North America.

Occupations and haptics without materiality

During the eighteenth century, Irish philosopher George Berkley wrote extensively about how touch and sight inform each other in An Essay Towards a New Theory of Vision. Within Chinese culture, the proverb “I hear I forget. I see I remember. I do I understand…” is derived from the writings of Master Xun from the Warring States Period (475-221 BCE). The connection between neurological development and multi-sensory stimulation was pioneered in early childhood education by the nineteenth century inventor of kindergartens: Friedrich Froebel. After working in an orphanage in Switzerland, he devised his pedagogical principles of utilising objects, like spheres, which he termed “gifts” and activities, like paper folding, which he called “occupations”. During the early twentieth century, influential physician and educator Maria Montessori similarly devised her pedagogical theories after working with disabled children in a psychiatric facility in Rome. “Muscular memory,” which she interpreted as a repository of “impressions” built up through “touching”, was a key concept.

In the early twenty-first century, psychologists and early childhood educators concur that multisensory simulation is integral to learning. Whether or not materiality, beyond a touch screen, is integral to this process remains a point of contention. Irrespective, due to the pandemic AR using personal mobile phones has presented museums and galleries an opportunity for continued interaction using the senses of sound and, to a limited extent, touch.

Conclusion

It is important to note that the application of AR in museums and galleries extends beyond the visual arts into natural history and science displays. Subsequently, it may be argued that there are two distinct trajectories for its development in the sector. This also would presume that the notion of the two conflating in art galleries is a misconception. However, their being differentiated by the acknowledgement of authorship makes this a disquieting co-existence.

The pioneers of AR art, not unlikely early Surrealists, used it as a form of political resistance. Tiananmen SquARed by 4Gentlement is a primary example. The similarities between the two movements also includes the uncanny and juxtaposition. However, the implications for the settlement on the Pokémon GO lawsuit in 2019 includes providing cultural centres and events with a legal precedent. This equips them to protect their geo-digital space from GPS/locative AR squatters.

Whilst this may bring an end to artist-led outbreaks of mass autonomism, curators and public program facilitators are generating their own smartphone flash mobs. Whereas some institutions, such as the UCCA in Beijing and the Boston Cyberart Gallery, are exhibiting the artwork of AR artists, other galleries are commissioning artists to augment existing two-dimensional artworks. In the case of the latter, when the material components and their creators are given precedence, the role of the augmenters is often treated as immaterial.

Although craft is a term ordinarily inextricable from the materiality, in this context the subcontracted artists are providing the mechanical assistance to create immaterial aspects. In a further departure from the Art and Craft Movement model, the digital elements represent internal realities. These imaginings would be, by Morris’s definition, aligned with the “Greater Arts”.

However, these institutionally instigated collaborations are often designed as a method of pedological engagement. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, AR art has presented an invaluable alternative to craft stations for audience interaction. Using their own handheld devices, the visitors are able to enhance their experience with sound and, to a limited extent, touch. Whilst psychologists and early childhood educators concur that multi-sensory stimulation increases the uptake of information, the role of materiality remains a point of contention. What is clear is that AR has been adopted by the cultural centres that early interventionist artists sought to thwart, and it is being used to enhance as opposed to disrupt the authority of the institutions.

Further reading

Archiscene. 2019. Flowing Eternity at Changsha Meixihu International Culture & Arts Centre. Archiscene. https://www.archiscene.net/cultural/flowing-eternity-changsha-meixihu-international-culture-arts-centre/

The Art Assignment. 2017. The Case for Surrealism. YouTube Video. (17 March, 2017). PBS Digital Studio, Arlington, VA. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wtPBOwE0Qn0

ARTETCH International. 2019. ARTECH 2019 Exhibition. ARTECH International, Braga, Portugal. http://2019.artech-international.org/artech-2019-artistic-program/

Aukstakalnis, S. 2016. Practical Augmented Reality: A Guide to the Technologies, Applications, and Human Factors for AR and VR. Pearson Education, Crawfordsville, IN.

Azuma, R. T. A Survey of Augmented Reality. Presence: Teleoperators and Visual Environments 6, 4 (August 1997), 355-385.

Barnhart, R.M. 1997. Three Thousand Years of Chinese painting. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Berkeley, G. 1709. An Essay Towards a New Theory of Vision. Aaron Rhames, Dublin UK.

Biography of Dr Maria Montessori. Montessori Australia, Noosaville QLD.

Chiu, K. 2020. Nintendo Files Chinese Trademarks for Pokemon Go in China, Where the Mobile AR Game is Currently Banned. South China Morning Post, Hong Kong.

Coates, C. 2020. How Museums are using Augmented Reality. Whitley Bay UK.

Craddock, R. 2019. Niantic Pays $4m In Pokémon GO Trespassing Lawsuit, Will Introduce New Reporting System. Nintendo Life, United Kingdom.

Favermann, M. 2016. Visual Arts Review: Augmented Reality – The Future Is Now. The Art Fuse, Somerville MA.

Friedman, M. “Falling into Disuse”: The Rise and Fall of Froebelian Mathematical Dolding within British Kindergartens. Paedagogica Historica, 54, 5 (2018), 564-587.

Gastel, T. V. 2020. Future Tech China: How Can Brands Best Leverage AR in China? Jing Daily, China.

Geroimenko, V. 2014. Augmented Reality Art: From an Emerging Technology to a Novel Creative Medium. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland.

Helena Papageorgiou. Helena Papageorgiou, Brisbane QLD.

Helena Papageorgiou. Second Variety. Helena Papageorgiou. Brisbane QLD.

Hemanth, D. J. and Estrela, V. V. 2017. Deep Learning for Image Processing Applications. IOS Press, Amsterdam.

Hillenbrand, M. 2017. Remaking Tank Man, in China. Journal of Visual Culture, 16, 2 (2017), 127-166.

Impossible Things. 2017. The Team. Impossible Things. Toronto, Ontario.

Jian, H. The Chinese Art of Papercutting. Youlin Magazine, Pakistan, 2016.

Las Ranetas Asociación Cultural. 2019. Trajakos Seleccionados 5th Ranetas VR Fest. Las Ranetas Asociacion Cultural, Alcaniz.

Liao, R. 2020. China Watches and Learns from the US in AR/VR Competition. San Fransico CA.

Lim, B.K. and P. Wen. 2017. Surviving Tiananmen ‘Gentlemen’ Mum on Chinese Nobel Laureate’s Death. Reuters.

Malt, J. 2004. Obscure Objects of Desire: Surrealism, Fetishism, and Politics. Oxford University Press, London UK.

Mark, J. J. 2020. Effects of the Black Death on Europe. Ancient History Encyclopedia Limited, Surrey UK.

Mayhew, A. and S. Hudson Hill. 2019. GY8C691. MuseumNext, Toronto ON.

Mirage: Contemporary Art in Augmented Reality. Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing. 2020.

Montessori, M. 2004. The Discovery of the Child. Aakar Books, New Delhi, Delhi.

Morris, W. 1882. The Lesser Arts of Life. Macmillan and Co, London UK.

Passavant, G. 2021. Andrea del Verrocchio. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Florence, Italy.

QUT Art Museum. 2020. miffy & friends. Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane QLD.

Randazzo, S. 2017. ‘Pokémon Go’ Suit Makes Case for Virtual Trespassing. Wall Street Journal, New York NY.

REBLINK. Art Gallery of Ontario. Toronto ON. 2017.

Saxby, J. 2020. If Walls Could Stalk. Look Magazine. Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney NSW.

Schmalstieg, D. and Höllerer, T. 2016. Augmented Reality: Principles and Practice. Addison-Wesley, Crawfordsville, IN.

Shadow Play: Tales of Urbanization in China. Creative Captial Foundation, New York.

Schumacher, P. 2008. Parametricism as Style – Parametricist Manifesto. Patrik Schumarcher, London.

Shams, L., Wozny, D., R. Kim and A. Seitz. Influences of Multisensory Experience on Subsequent Unisensory Processing. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 264 (2011).

Spalter, A. M. The Computer in the Visual Arts. Addison Wesley Longman, Reading, MA, 1999.

Tracxin. 2020. Augmented Reality Startups in China. Tracxin, Karnataka, India.

Veenhof, S. 2010. DIY Day. SNDRV.

Volpe, G. and M. Gori. Multisensory Interactive Technologies for Primary Education: From Science to Technology. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(2019), 1076-1076.

Werner, J. 2017. Augmented Reality. YouTube Video. (4 August, 2017). TEDx Talks, Asbury Park NJ.

Werner, J. 2019. How Augmented Reality Can Give Us Superpowers. YouTube Video. (8 June, 2019). TEDx Talks, Atlanta.

Yargs, S. 2019. Origin of “I Hear and I Forget. I See and I Remember. I Do and I Understand.”? English Language & Usage. StackExchange, New York NY.

Zhang, D. 1989. The Art of Chinese Papercuts. Foreign Languages Press, Beijing, China.

Zuckerman, O. Designing Digital Objects for Learning: Lessons from Froebel and Montessori. International Journal of Arts and Technology, 3(2010), 124-135.

4Gentlemen. Tiananmen SquARed. Augmentationist International.

About Pamela See

Pamela See (Xue Mei-Ling) has a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) from Griffith University and a Master of Business, majoring in public relations, from the Queensland University of Technology (QUT). In addition to regularly contributing to Garland Magazine, she has also written articles for M/C Journal, Art Education Australia and 716 Craft Design. Her research interests include: craft, post-digitalism, Asian art, public art and participatory art.

Pamela See (Xue Mei-Ling) has a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) from Griffith University and a Master of Business, majoring in public relations, from the Queensland University of Technology (QUT). In addition to regularly contributing to Garland Magazine, she has also written articles for M/C Journal, Art Education Australia and 716 Craft Design. Her research interests include: craft, post-digitalism, Asian art, public art and participatory art.