Priyanka Kochar reflects on her ancestors’ meticulous hand-bound account books.

Generation after generation, how we live, eat, earn, shop, and spend evolves, shaped by the shifting zeitgeist of each era. Every decade brings a fresh perspective, a new rhythm of life. Some traditions endure, becoming timeless, while others quietly fade away. In Indian households, however, there exists a deep-rooted tradition of passing down not only possessions but also habits, rituals, and values. Within this legacy lies a profound respect for systems that have stood the test of time, such as the ancient art of handwritten accounting.

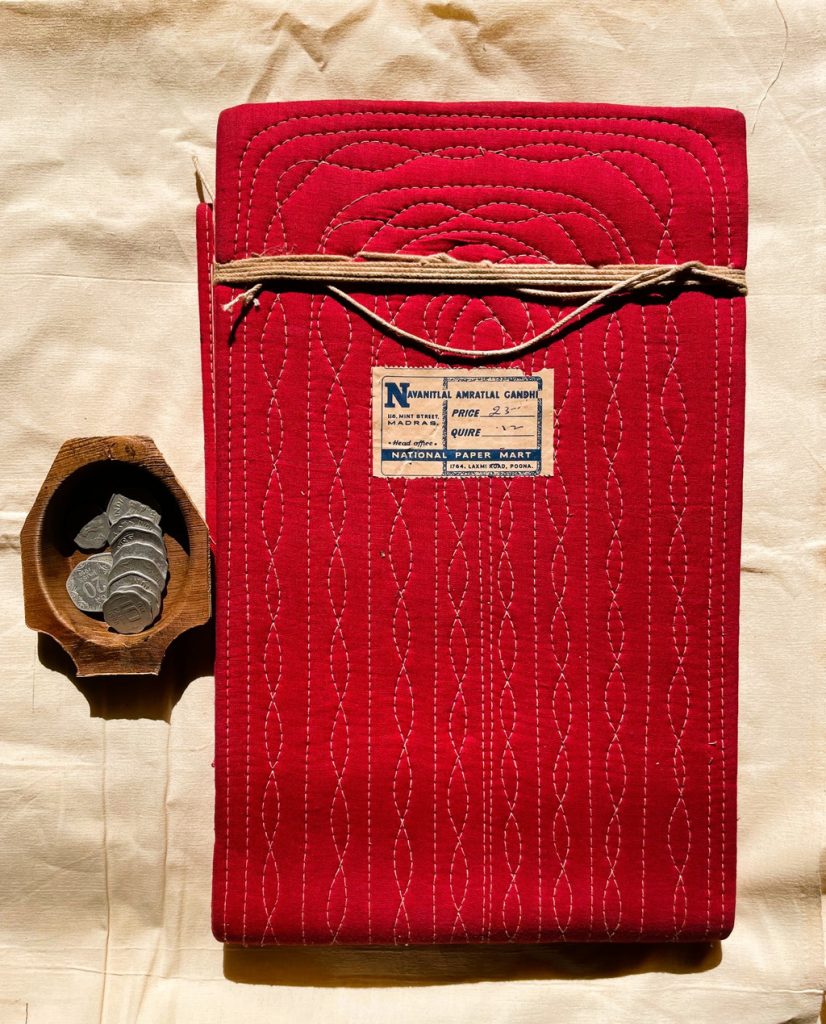

Before the age of spreadsheets and cloud-based finance tools, India’s trading communities relied on meticulously maintained, hand-bound account books known as Bahi Khata. Particularly prominent in Rajasthan and Gujarat, this traditional bookkeeping method—Desi Nama—is more than a ledger. It’s a cultural artifact, a spiritual practice, and a window into the ethos of a bygone era.

The term Bahi Khata combines Bahi (book) and Khata (account). These ledgers were revered as sacred objects and were believed to invite the blessings of Goddess Lakshmi, the deity of wealth and prosperity. To many, they were more than financial records—they were talismans of divine favour.

Every afternoon, my elders would gather to update the day’s accounts using a bark pen dipped in ink.

Growing up, I witnessed generations in my family carefully maintain a red cloth-bound ledger, wrapped in soft white muslin and stored in fragrant wooden cabinets that seemed to whisper stories of the past. Every afternoon, my elders would gather to update the day’s accounts using a bark pen dipped in ink. Each entry was a ritual, each page a testament to order and clarity. Separate books were designated for different accounts. Even women, often managing the household economy, maintained their own Khata Bahi for daily expenses—these too were locked away with great care, their keys entrusted only to the family head.

The craft of Bahi Khata

- Front fold of bahi khata

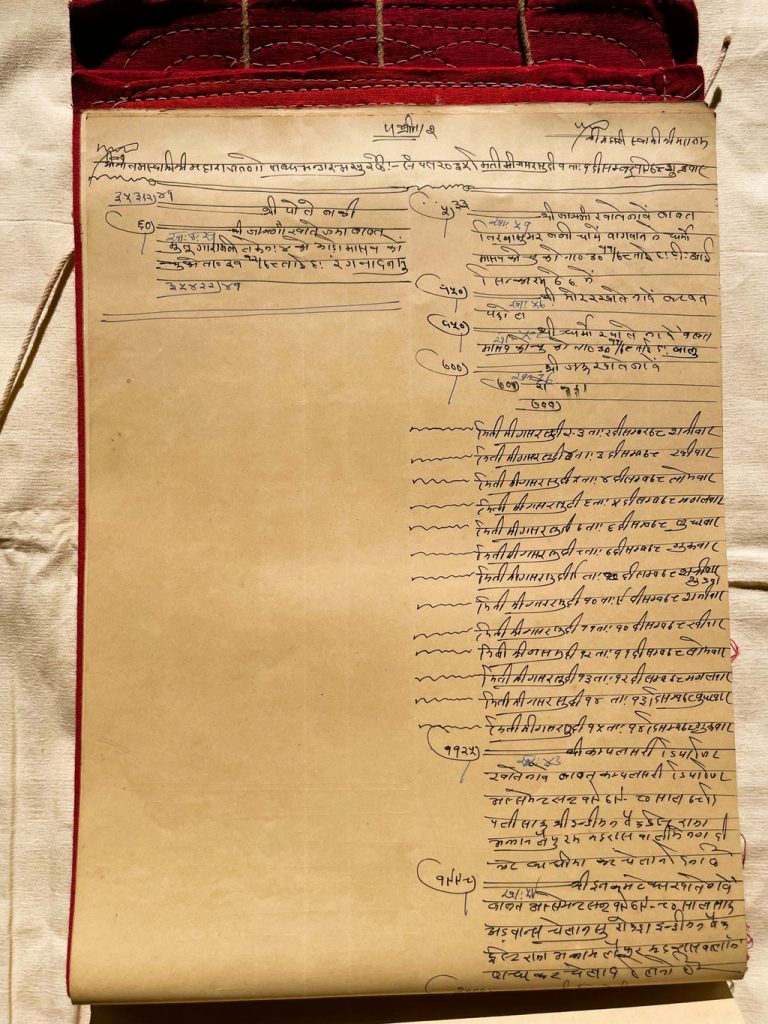

- Calligraphy style

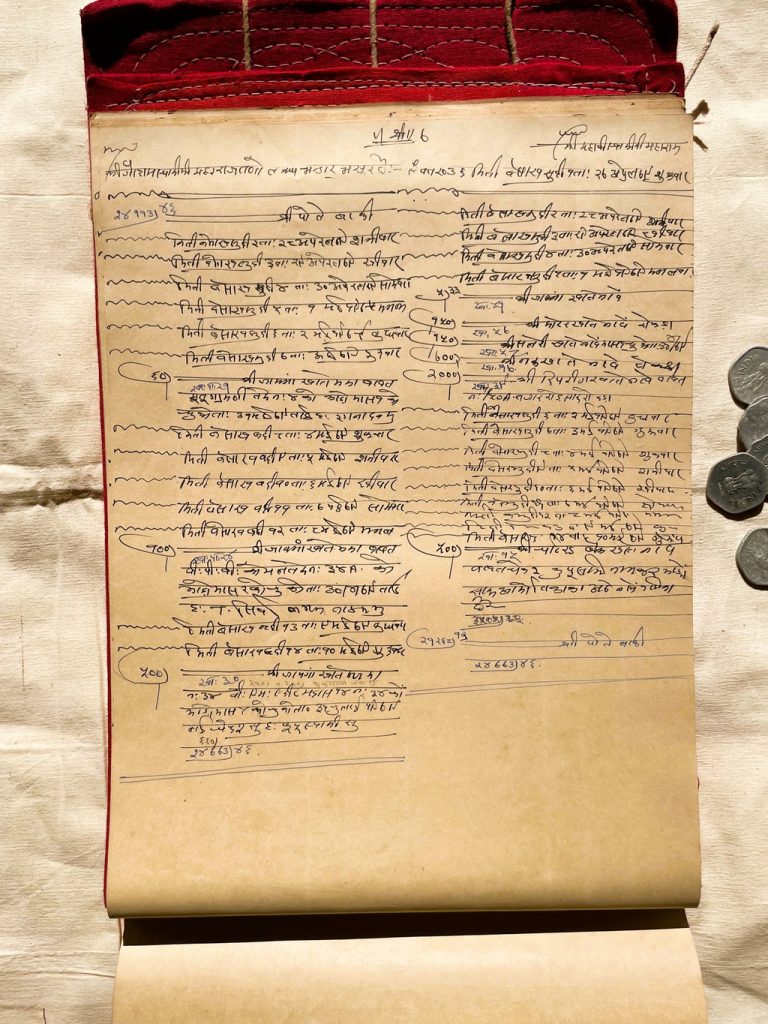

- Debit and credit

- Folds of bahi khata

Simple yet artful, these books are crafted from just four materials:

- Red cotton cloth

- White coarse thread

- Cardboard

- Paper

The process begins by sandwiching cardboard between red cotton cloth, stitched loosely in an uneven pattern on a sewing machine. Sheets of paper are cut and folded into eight equal sections called sal. These folds serve as invisible columns: four on the left for jama (credits), and four on the right for udhaar (debits). The first fold records the amount, while the following three detail the affected account. This elegant structure made the system easy to use, even without ruled lines.

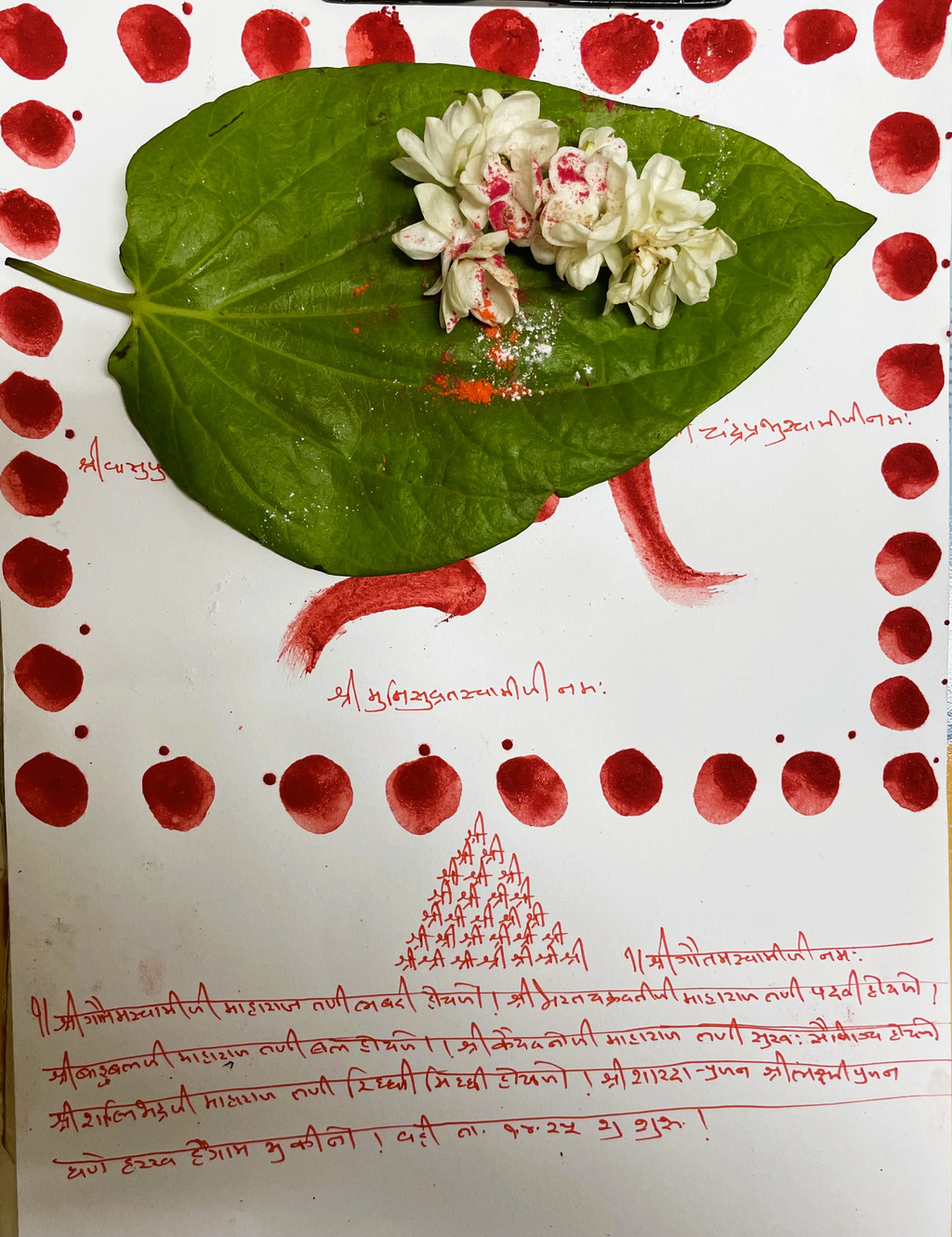

Each page begins with an invocation—“Shree Ganeshaya Namah” or simply “Om”—inviting auspiciousness into every financial transaction. The language used was often vernacular, and the calligraphy was personal yet precise. Trust and confidentiality were embedded in every stroke. Mistakes, smudges, or scratched-out lines were rare; they suggested carelessness or, worse, deceit.

More Than Just Accounting

The first page of every new ledger carried spiritual significance. A hand-drawn Swastika—a symbol of prosperity—was embellished with red vermilion, turmeric, and nine sacred dots representing the planets. Silver coins, betel leaves, and flowers were placed on this symbol before the year’s first entry. Often, the names of ancestors, gods, and goddesses were inscribed to bless the book, marking a sacred beginning to the financial year. A pyramid-style writing of the word “Shree” was also used.

Handwriting was considered a mirror to one’s character. A neat, graceful script suggested integrity and attentiveness. These books weren’t merely tools of trade—they were reflections of ethical living. Many even viewed them as karmic ledgers, subtly reminding us to keep not just our financial records, but our moral accounts in order.

Bahi Khata Today

While modern businesses have migrated mainly to digital accounting systems, the Bahi Khata hasn’t disappeared entirely. In many parts of western India—particularly in Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra—families still purchase these ledgers each year during the festival of Diwali to invoke prosperity for the coming year. For others, they’ve taken on new life as collectibles, journals, or sketchbooks—reimagined for a new generation.

The fading ink and hand-stitched spines of these red-cloth books reveal a beautiful paradox: permanence in impermanence. They remind us that even in a fast-moving digital world, there’s grace in slowing down, putting pen to paper, and honouring the craftsmanship of a life well-accounted for.

About Priyanka Kochar

Priyanka Kochar is a fashion writer, stylist and design academician based in India. With over fifteen years of work experience across various disciplines related to design, she has published works in some of the prestigious fashion magazines across the globe. Apart from styling for campaigns and brands, she also teaches fashion communication at some of the most prestigious fashion colleges in India. With a keen interest in sustainability, she spearheads various events and partnerships for sustainable fashion.

Priyanka Kochar is a fashion writer, stylist and design academician based in India. With over fifteen years of work experience across various disciplines related to design, she has published works in some of the prestigious fashion magazines across the globe. Apart from styling for campaigns and brands, she also teaches fashion communication at some of the most prestigious fashion colleges in India. With a keen interest in sustainability, she spearheads various events and partnerships for sustainable fashion.