Dias Prabu at work

Elly Kent follows the path of batik as a way to explore the complex dynamic of Indonesian culture and to discover a much-needed optimism for our time.

(A message to the reader.)

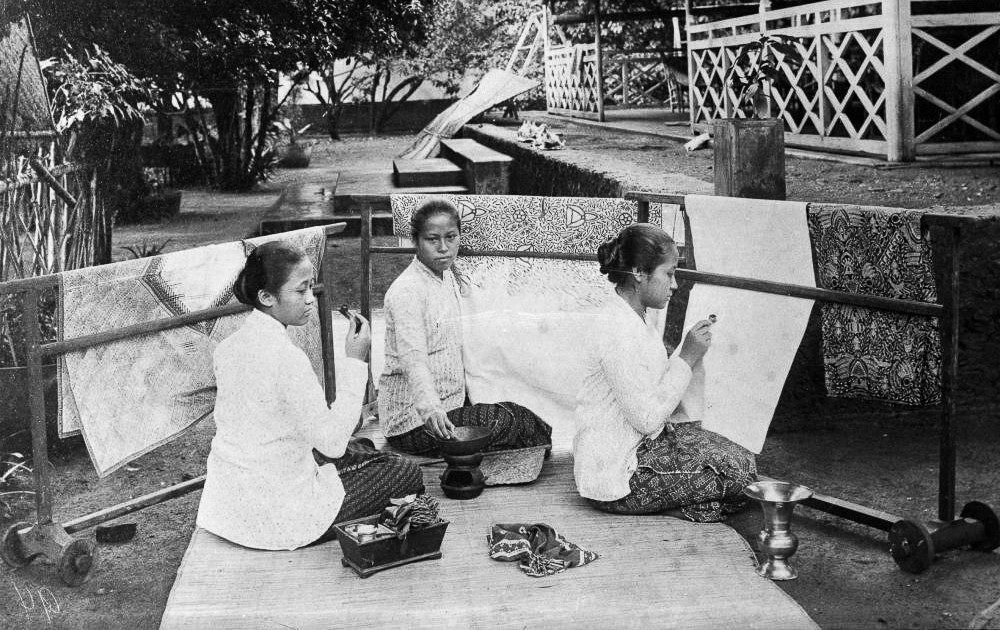

Making at Babaran Segeragunung

On this particular morning in 2018, the heat was, to reprise a cliché, oppressive. The wet season was out of sync and the humid air of Yogyakarta in February was trapped against the streets by a haze of petrol fumes. The sunlight was a sharp, nostalgic yellow interspersed with long blue shadows as I waited for my motorcycle taxi, or ojek, outside my homestay.

The temperature dropped as the concrete receded behind us on the journey to the southeastern skirts of the city. More green filtered into my vision, colourful murals became rarer, walls lower, vehicles fewer. Rice fields rolled out across the low hills, punctuated by occasional double-storey dwellings, their façades brightly painted and sides left raw with white mortar oozing between the bricks. Here and there a copse of trees promised cool shade and everywhere vines and palms proliferated. The cooler air was palpable on the back of the bike, but when I dismounted the humidity caught in my throat again. It was like breathing soup.

I was visiting Babaran Segera Gunung for the first time, to check in with a student whom I’d placed with the batik studio Babaran Segera Gunung, as part of a practicum course I was teaching with the Australian Consortium for In-Country Indonesian Studies (ACICIS). From the front, the complex seems an unassuming house, with the ubiquitous features of Southeast Asian vernacular architecture. A red-tiled pyramid roof looms behind a cement block wall just high enough to block the vision of the casual passer-by. An enormous metal gate rolled away to allow me into the embrace of Nia Fliam, who, along with creative and life partner Agus Ismoyo, has made this small semi-rural block into a hidden batik paradise. We slipped around the side, through another gate, down a pebbled path into the studio garden. To the left a pendopo functions as a meeting area, dining room, presentation space and shelter from the sun and rain. Scattered throughout the garden, narrow buildings line the boundaries, a cluster of them, including a smaller pendopo, surround a pond carpeted by lily-pads.

Depending on the day you visit, the open grassy area in the centre of the garden might have fluttering fabric hanging from lines stretched across it, or a turkey might strut across your path. There may be women seated in one of the deep verandas, carefully applying hot wax to fabric draped across a bamboo frame, following pencilled lines that flow across the surface of the cloth. Elsewhere you might catch the scent of a larger stove of wax, where tjap—large copper and wooden stamps—slip motifs into the fibres of cloth under the practised hand of Ismoyo or one of his assistants.

On this day there were no colours fluttering on the lawn; clouds were building and rain was imminent. The sunlight, burning through the clouds intermittently, created a startling contrast between bright green leaves overhead and the dark blue-grey sky behind them.

I’d also come for lunch, and I’d cleared my afternoon on Nia’s invitation to spend some time making with them. We sat down on the cool tiles as Nia took us through some basics. We practised using folds, ties and brush techniques to manipulate the wax and dye’s encounter with the warp and weft. We cracked the wax surface to create apertures for the indigo to sink through, or fold and clamp to keep dye from the edges. As we took up the wooden-handled tjanting, we dipped the small copper well into the hot wax, which runs through a narrow nib to the fabric. I began to feel like I was swimming in warm water. I can’t tell if the sheen that covers my skin is sweat or precipitation in the air.

Suddenly, relief. The rain is torrential. The temperature and the air pressure drop and we slip further into meditative repetition, dipping, steadying the flow and drawing the nib across the fabric gently, making sure our hands move slowly enough for the wax to absorb through both sides of the cloth. With the white noise of the rain, I lose track of time. The warm wafting scent of the wax drifts returns my mind to childhood church masses, that longed-for moment when the procession of priest and acolytes is preceded down the aisle by a swinging, smoking thurible, frankincense and myrrh smouldering within.

In an essay recounting her interviews with master batik artist (or an empu, within Javanese tradition), Ibu Hartinah, Nia describes how this process “has a magic of leading the maker into an atmosphere of larashati or calmness.” The deep state of emptiness that repetition of action and form, coupled with the sensory cues of sound, smell and sensation, induces in me is one that has permeated my creative practice since my early training in printmaking and drawing at the ANU’s (then) School of Art.

The more repetitious the process required to create an image, the more I was drawn to it. Hours grinding lithography stones with ever finer grit and cold Canberra water, to achieve the smoothest surface possible oblivious of numbing fingers. Lifting an anchored screen, carefully aligning the substrate, lowering, swiping ink across the silk and slowly sliding the squeegee down. I invented designs and installations that demanded long late nights walking the creaky parquetry floor of the print studios.

APT via Utopia collaborations

I first saw Nia and Ismoyo’s work at the very beginning of my studies, the culmination of a long road trip from Canberra to Brisbane in my ageing Ford Escort with “manual air conditioning”. We arrived in Brisbane lost and quarrelsome, my partner navigating from a fold-out paper map while I steered through narrow, glaring streets. As we pitched our tent, the radio announcer announced a record high temperature; we stopped bickering and blamed the heat. The next day we were cool and young in the Queensland Art Gallery, drinking in the third Asia Pacific Triennial and falling hard for contemporary art. Throughout the exhibition, works startled and provoked impressions that, as an undergraduate in Asian Studies and Visual Arts, never left me. Many of the artists whose work I discovered there later became my teachers, mentors, the subjects of my research, appeared in exhibitions on which I worked, or became collaborators in intellectual and creative practice as well as dear friends.

Nia and Ismoyo’s collaborations with the batik artists from Utopia, in Central Australia, were cast in this exhibition as “border crossing” works, the result of cross-cultural interactions that Astri Wright refers to as not merely “using the same words in the same ways” but rather “achieved through the use of faculties of deep listening and visioning”. This focus on the permeation of boundaries “between past and future and between craft, tradition and contemporary art” as well as between maker and audience, individual and community, marked the APT3 as a ground-breaking exercise in recognising the way art is practised outside of (or away from) the Western canon. The major work on display from the Utopia/Brahma Tirta Sari collaboration, a 10-metre length of textile titled Sekar Pucung—Songs of the Ancestors/Batik Apmer-Areny, was created over several years. It involved the use of tjaps that were created in Yogyakarta from drawings made by the Utopian women and sent ahead of them their visit to Brahma Tirta Sari, Nia and Ismoyo’s batik studio, in 1994. A later visit from Nia and Ismoyo to Utopia in 1995 allowed them deep immersion in the stories, law and culture of their indigenous co-creators. Recalling this formative experience on his practice, Ismoyo said “The Aboriginals had the sensitivity, evident in them singing the songs of their ancestors; they believe nature is their ancestor. It is such a delicate law.”

A deep respect for indigenous culture and law permeates Nia and Ismoyo’s life-work and philosophies, through their early “ISNIA” collaborations, made while absorbing the complex “knowledge culture” of Javanese science/spiritualism from Ismoyo’s father—a recognised master in the field— and throughout their works with indigenous peoples in Australia, the Americas and Africa. The development of this knowledge culture (I borrow the term from Astri Wright) and their explorations of other indigenous knowledge systems through creative immersion and collaboration with practitioners, has manifested not only in physical artworks of increasing complexity, but also in their intellectual engagement in aligning ancient ways of knowing and being (“traditions” perhaps) with the challenges that modernity, colonisation, globalisation and industrialisation have visited on humankind and the planet we reside on.

This baseline of ancestral wisdom is, for Nia and Ismoyo, the philosophy of Tribawana (the Three Worlds). They write that this concept “shows us that we live within these three worlds. As humans, we have our own micro-cosmos or ‘small world.’ As sentient beings, we also exist within a larger universe and so we are connected to nature, all living beings and matter, which is the macro-cosmos / the universe or ‘big world.’ Finally, we are all connected to the immaterial or unseen world, which is the source of all creativity. Tribawana, therefore, is the self in connection to the environment and the source of creativity.”

The semen pattern on a hand-made batik cloth.

On that day in 2018, we began our lessons with a kinetic introduction to batik as a body of knowledge based on the concept of Tribawana. Using the prized semen pattern as an example, Ismoyo explained how each motif, each stem, flower and tendril of the alas-alasan (foliage pattern), each stylised bird and insect, is linked symbolically to the whole pattern, signifying our interconnection with the universe and its creative drive through Tribawana. It’s ambiguous background, which can be white and/or black, hints at the simultaneous existence of seen and unseen worlds. These patterns of meaning, Ismoyo reminds us, echo not just in the fabric but also through other forms and expressions of Javanese culture: the shadows of wayang puppets reveal a narrative that unfolds before our eyes, yet the puppets are unseen—in spite of their fine and ornate crafting. In turn, they depict a world that is past, present and parallel to ours, neither history nor mythology, not partitioned from our reality but rarely tangible within it.

Continuity…

Relocating and reinstating a continuity of knowledge between the past and the present, whether at a personal, micro-level or on a grander, macro scale, is a familiar process within Indonesian art, and in batik in particular. In many of his essays, art historian, critic and theorist Sanento Yuliman (1942-1992) explored how a lack-of-rupture contributed to the formation of a modernism distinct from that proposed by Euro-American theorists like Clement Greenberg.

In writing that appeared in major daily papers, magazines and scholarly journals, and has recently been republished in their entirety in a series of new volumes, Yuliman gave evidence of the instability of hierarchies of high and low art, and their mutual influence on each other in Indonesian culture. In 1984, he pointed out that the aesthetic reproduced in the landscape paintings on becaks (trishaws) is indebted to the mooi Indië (beautiful Indies) paintings that preeminent Indonesian modernist S. Soedjojono, in 1946, rejected due to the genre’s links to European artists and their colonising, romanticising eyes (1946). He drew attention to the fact that the so-called “tradition” of glass painting is a relatively recent phenomenon. Through many of his essays, we can see that Yuliman understood the task of the art historian in Indonesia to involve deconstructing the divisions that modernism constructs between art and craft, thought and action, function and philosophy, past and present. When I first read his work I was struck by how much his approaches seemed to foreshadow the ”departitioning” that French philosopher Jacque Ranciere proposed through his aesthetic regime: the idea that all of the categories and taxonomies we use to frame our understanding of not just art, but every aspect of life, deliberately obscure reality from us, forcing us to see binaries—and therefore choices, decisions, conundrums—where they may not exist.

Arguably, this is most apparent in the false binary between autonomy and heteronomy, the valorisation of artists’ individual creativity and the notion that it precludes the participation or influence of others and the external world, a tenet of “Western” modernism that failed to transfer into Indonesian discourse. Instead, the fundamentally collective and socially-oriented nature of the arts, still embedded in the lives of most citizens of the newly formed nation, carried through into modern art. Soedjojono made the lofty declaration that beauty lies in truth, demanding Indonesian painters making visible their own souls by painting their social reality, an approach that later became an imperative for all creative practitioners as the leftist Institute for People’s Culture mandated turba, “going down” to the people in order be able to reflect the revolutionary aspiration of “combining individual creativity with the wisdom of the many”.

Curator Jim Supangkat (also a long-time collaborator of Yuliman’s) drew attention to this relational aspect of both the philosophy and practice of batik in his introduction to the BTS/Utopia collaboration in the APT3 catalogue, underlining its temporal as well as social implications. “The tradition underpinning these collaborative works is more than just a means by which collectivity is reflected through artistic arrangement. It also encompasses the collective unconscious, where individuality is not considered a pole that opposes collectivity, but the result of tensions between the collective unconscious and the ego as the centre of consciousness.”

Ethics and aesthetics

Ismoyo’s instruction on these matters of great significance to him was gifted to us with the generous intention of developing our own capacity to generate creativity through connection with the universe. He is revealing his most valuable lesson and sharing the basis of his practice with us freely, in a sense because he understands it to be a universal truth reflected in all indigenous knowledge systems, and therefore not just “his” at all. It is a fundamentally heteronomous understanding of the process of creativity and one at odds with what both I and my student have been schooled in through our art and design training. Ismoyo encourages us to join him in a series of poses and movements, not unlike yoga, and to express vocally and physically in order to refine our connection. My student baulked at this unexpected requirement of her studies—and perhaps I would have too had this been a part of my first lessons in batik. As foreigners, we were caught in a trap that reminds us of our otherness, our legacy as descendants, by birth or association, of colonisers and invaders; we checked the dangers of cultural appropriation and the slippery slope of mysticism that might lead—well, who knows where?

As a foreigner, should I be trying to tap into batik as though it is any other form of mark-making? Or should the problem be flipped (I imagine Yuliman and Ranciére would approve): should all mark-making be driven by a deliberate and conscious relationship with the universe, regardless of the culture or philosophy it emerges from? This is the collective consciousness that Supangkat referred to.

It is hard to unlearn the habits of a lifetime and the training and education that overlays the social norms of one’s culture with processes, goals and expectations based on those norms. I was not raised in mysticism, but nonetheless listening to my grandparents murmuring their rosaries through the bedroom wall always reminded me of the possibility of unseen powers. For monotheists, I suppose, that power is centralised and, in a sense, external, above and alienable. Beseechable. Not a universal drive that resonates through all life forms in the micro and the macro, the seen and unseen. In spite, or perhaps because of my unmystical upbringing, Tribawana seems like a more “scientific” proposition. “We are stardust,” the song-lines of my life have told me. Clifford Geertz wrote that in Java, the batik process itself is perceived as an analogy for mystical experiences which imprint a motif on the heart.

Micro-cosmos

When I was 17, my parents gifted me a tome titled Textiles of Southeast Asia, Tradition Trade and Transformation. Partly based on the National Gallery of Australia’s extensive collection, it traced the stories—histories, mythologies, functions, flows and evolutions—of making, distributing and using fabric, in everyday life, death, patronage and politics. What intrigued me most then were the patterns. Intricately complex codes of meaning and function, painstakingly recorded over decades of research by many dedicated individuals, and intriguing in their pasts and possibilities. When I went to art school three years later, I didn’t take textiles but instead studied printmaking and drawing. In printmaking, I could explore patterns to my heart’s content. In my Asian studies’ degree, I was exposed to Said’s Orientalism, post-structuralism and cultural studies. All played in tension with my desire to draw on these familiar yet strange motifs in my own work. I also studied Asian art and architecture, spending blissful hours in the dark watching slide lectures given by Robyn Maxwell, author of the book that had captivated me.

In my third year at university, I travelled to Yogyakarta as an ACICIS student myself. I spent a semester studying ethnography and sociology at the main university, Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM, named for the great general and prime-minister of the Hindu kingdom of Majapahit), and then another at the Institute of Indonesian Art, taking a strange mix of kriya, or fine crafts, and printmaking. It was creatively formative, but my memories are patchy. In an extra-curricular course at UGM, I used brushes and tjanting to create a rather cloyingly Australiana pattern of gum leaves and blossoms against a crackle background. One afternoon, working in my tiny homestay, I managed to tip molten wax down my leg; the scar still reappears when I get too much sun. After that year, wax and patterns remained integral to my practice but my wok and tjanting slept at the bottom of the cupboard. Perhaps making batik seemed to demand an all-consuming commitment? A calling rather than a pursuit?

Yuliman saw batik as an exemplar for the search for “Indonesian-ness” that had dominated discourse since the conception of the nation-state. This struggle perpetuates a kind of “tradition of change” that sees art forms in a constant quest to progress, borrow and adapt, refine technique and technology, deepen the complexities of motif and meaning, and to embed artforms ever more deeply into the social practices of the archipelago. Batik is, according to Yuliman, an explorer: “it spreads in all directions and experiments with different approaches that have no precedent. I want to underscore the historical reality that reveals how this explorative element in batik…my image of batik is a dynamic, and this dynamism is an intrinsic element of batik.”

Macro-cosmos

The notion of batik as an explorer has geographic as well as temporal implications; and capital and political ones. Although UNESCO recognises batik as the intangible cultural heritage of Indonesia, its origins are not strictly Javanese. Archaeological evidence suggests it was practised in southern China during the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) and spread from there to Japan by the eighth century. But the origin and timing of its widespread appearance across Southeast Asia are less clear. Batik processes can be found among the Hmong and the Toraja, and perhaps even the Manobo of Mindanao (Maxwell). The tools that we recognise today, the use of the tjanting and tjap, are relatively recent technological advances on its timeline. The emergence of the Javanese tjanting in the seventeenth or eighteenth century has been linked to the development of more intricate and complex patterns, while the tjap is a modern invention from the nineteenth century that led, according to Maxwell, to incursions of men into practices previously exclusively the preserve of women. The gendered nature of batik continues today. It’s rare (although not unheard of) to see men use tjanting or women use tjap.

Even a definition of batik is hard to pin down. Is it simply a variation of the resist dyeing processes practised by many cultures (including the earliest precedents known in West Java, kain simbut, which utilised a flour-based paste)? Is the use of wax a defining feature, or its application to textiles? Or is it the suite of patterns that perform important spiritual and social functions within the distinct culture of the Javanese? Is it a noun, the fabric that results? In the vernacular we can “buy batik”, but it is often not the result of a batik process. And what to make of recent development in which motifs from other ethnic textile traditions are now denoted as batik when they appear in factory-produced printed cloth—batik Dayak or batik Batak. In 1990, perhaps foreshadowing these problematic developments, Yuliman warned: “that exploration, in the present era, cannot be continued at random: it must now be an exploration that is conscious, planned and critical.”

Batik has not evolved in a vacuum. Trade and geopolitical exchange has always influenced its motifs, aesthetics and production processes. Indian, Islamic, Chinese and European influences on the motifs that have been ascribed as particular to Java are nonetheless frequently recognisable in the ornaments of other places. Of these, my favourite is mega mendung, the looming, layered storm cloud that curls across many cloths, and is closely tied to the courts of Cirebon, an important port town and entry point for the ancestors of many Chinese Indonesians. Peranakan families featured prominently in the production and distribution of batik within the archipelago and beyond in the nineteenth century, adding and adapting motifs. Their persistent transnationalism freed them from some of the conventions and traditions of both cultures, and Chinese-managed batik studios were early adopters of progressive technologies.

Another intriguing manifestation of the explorative nature of batik is the remarkable development of tiga negri (three-region) cloths, fueled by the arrival of the locomotive. Curator at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Dr Matt Cox, wrote on the evolution of the tiga negri cloth: ”When the coal black metallic train tracks were first networked across the green landscape, for many, they must have seemed like yet another manifestation of the tentacles of Dutch colonial enterprise enriching itself through the extraction of natural resource, now at even faster speeds.”

Batik, ever the explorer, rode this new network too, as studios along the north coast of Java added their specialist motifs and dyes to cloth before passing it along the line. The increased entrenchment of the Dutch over the nineteenth century, shifting from commercial to colonial exploitation, also brought new patterns and influences. The Arts and Craft movement, reacting to the industrialisation of production in Europe, sought to revive the value of finely hand-made objects, and as Maxell described, a “conscious interplay of designs and techniques between Java and the Netherlands” resulted. Later Art Nouveau also influenced batik, leading commercial batik studios to adopt Japanese themes.

By now men were frequently influential in the production, distribution and promotion of batik, but women retained instrumental roles in the industry, establishing and directing influential ateliers. They continued a tradition in Java by which residents of batik-producing villages near the cemeteries of the Islamic sultanates receive tax-exemptions in return for maintaining shrines and significant sites. The labour freed through this arrangement was invested in developing artistic skills; in these communities, female relatives of Muslim leaders controlled batik production.

One person who has become synonymous with the notion of the anonymous female batik artist is the woman seen by many Indonesians as the archetypal mother figure to the nation, Raden Adjeng Kartini (1879-1904). Kartini and her sister Roekmini (1880-1951), were designers, painter and batik artists, as were many women in the aristocratic Javanese and Eurasian population. In fact, they were for many years the archetypal batik artist for school children in the Netherlands, where a photograph of Kartini and her sisters was used to illustrate text books about the Dutch East Indies. Advocating for women’s and girls’ rights, Kartini saw the development of skills in art and design as a potentially emancipatory tool, both for her gender and for her people; her advocacy for Javanese fine arts became part of a broader international resistance to the mechanisation of art. The fear that technology was erasing the “aura” of the original artwork (as Walter Benjamin articulated) was in contrast to the immense social change—indeed the acceleration of resistance to colonisation and the imagining of new nations—that was driven by the industrial revolution.

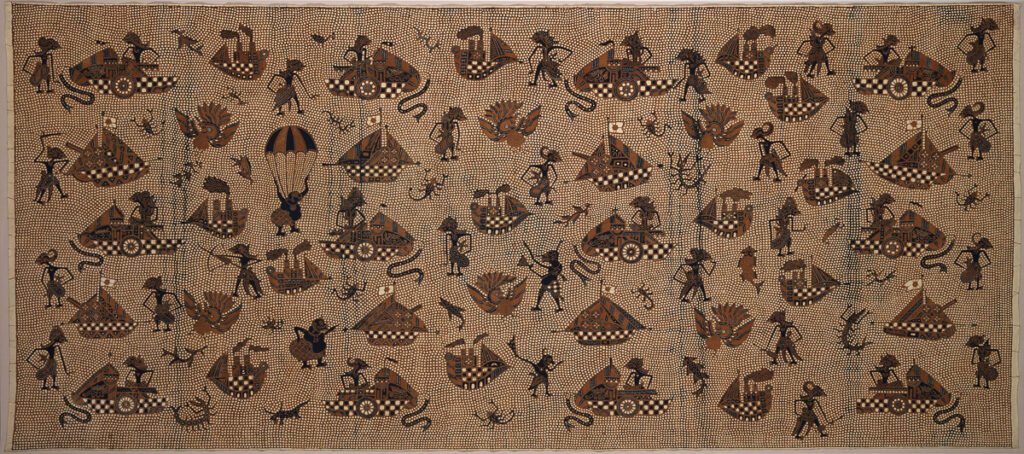

I too was enthralled by the Arts and Crafts movement as a student. I kept a copy of The Grammar of Ornament on my desk throughout my undergraduate degree, and a plethora of encounters through exhibitions, travel and study ensured I was always drawn back to pattern. Among the exhibitions was the National Gallery of Australia’s monumental Sari to Sarong: 500 years of Indian and Indonesian textile exchange exhibition. It revealed not only a stunning range of textile processes—ikat, tenun, songket, painting, embroidery, applique, batik—but also aesthetic decisions that responded to the contexts contemporary to their making, such as documenting steamships or adapting motifs favoured in export markets with local narratives.

Batik in its explorations, as Yuliman exhorts, is “selective and cumulative…it doesn’t throw away everything it has gathered in its journey, not without consideration and selection.” One particular kain panjang (long cloth) from that exhibition exemplified this selective retention and gathering. Dated to the Japanese occupation during the Pacific War, the cloth depicts a legendary battle of the Mahabharata, the great Hindu epic that also plays out in Javanese shadow puppetry. Silhouetted wayang figures—Arjuna the archer, Bima with his weaponised fingernails—accompany armoured vehicles, repelling ships that fly the Japanese flag. The great servant-clown, Semar, parachutes through the scene, appearing to direct the action, which is set against the background of the protective geringsing pattern, created by thousands of titik (dots) of wax covering the surface. What would an artist statement from the unidentified creator/s of this remarkable scene tell us? Does this cloth seem to absorb the terrifying ordeals endured under the Japanese occupation into an understanding of events that is cyclical rather than linear, timeless rather than historicised?

Contemporary batik?

In 2010, I travelled to Jogja yet again, this time with my young family on an Asialink residency at the Indonesian Visual Arts Archive, exploring approaches to children’s’ education programs. Through a convoluted set of chance meetings, I was introduced to Nia and Ismoyo as they prepared for the third iteration of Fibre Face, a major fibre art exhibition.

After that trip, I decided, as part of my doctoral studies, to refocus my practice on exploring batik as a process in conversation with notions of industry and domesticity. After many months of experimenting, I developed a series of works on paper, stamping wax across the surface with improvised tjap: potato mashers, coffee plungers, carving forks and screws. Over this I washed “dyes” that were made from cement pigment dissolved in water, resulting in deep, flat colours and raised, yellowish patterns. Stretched over repurposed insect screens, the works took on the dimensions of doors and windows, liminal portals signifying the threshold between those partitions Yuliman wanted to dissolve: high and low arts, the vernacular and the sublime, fine art and craft.

tjap.

The social, relational significance of batik was equally as intriguing and, as my research was intended to examine how artists de-partition autonomous and heteronomous practices, I worked with groups of school students to design and exchange an enormous collaboration called People and Place. Visiting schools in Canberra, Goulburn, Yogyakarta and Muntilan, I guided students through a process of designing a motif to represent their place and adding it to a 6 x 12 metre cloth. A microcosm of the social dynamics of design emerged: some uniformity and diversity due to availability of different materials in each school, “good ideas” spreading from group to group. Some discussions and examples garnered more interest from particular groups. The tjap I introduced fascinated the Yogyakarta school children, perhaps because the familiar pattern was common in their school’s environment within the Sultan’s inner sanctum in Yogyakarta. Canberra children had studied Expressionism and so used abstract and minimalist compositions to evoke place. In Goulburn, the high school students’ cognitive development produced symbolic representations of complex concepts like the contrasting environmental conditions of flood and drought. The tiny students of Sekolah Gajah Wong, a free preschool for children in a squatter community, used the plastic drink bottles their parents and neighbours collect for cash as tjap.

People and Place was finalised during two years of field study in Indonesia, during which I was also able to revisit my own formative people and places. Visiting Jogja in 2013 I dropped into Cemeti Art House, and joined a discussion on Dobrak, a curatorial project experimenting with interdisciplinary collaboration. In the exhibition space, large sheets of tjap-printed batik were stretched across one wall, while in front a “found” batik tablecloth hovered suspended in the air as a projector cast an animated line-drawing of figures turning themselves inside-out of each other. As I approached the wall the pattern there also revealed itself to be built from a series of figures, interlocked one below the other by hands reaching down to cover each other’s eyes.

These works were produced by Restu Ratnaningtyas from research and conversations with musician and sociologist Leilani Hermiasih which took the pair to the batik district of Giriloyo. Here they spent time in the home of Ibu Hartinah, whose knowledge and memories of a career that began in the mid-twentieth century span vast changes in the value, distribution and social function of batik, also informed Nia’s early research into the history of batik production. Restu’s work uses drawing and watercolour to create disturbing and mysterious reflections on gender, domesticity and fractured social relationships, behaviours and hierarchies. The cognitive dissonance between perceptions of batik as a reified, static national tradition and the existential threat of mass production to the art, as well as the artisans, prompted her to design her own seamless tjap pattern.

The title of these works, Merantai, or Chaining, offers a variety of potential interpretations: the chains that bind artisans to their inherited craft and its sacred motifs; the chain of production that tied generations of Giriloyo residents to the palace and its instructions; the chains of domesticity which keep women’s work, even when it is the primary income of a household, beholden to patriarchal constructs of the public domain as male, and the private as female. As these constructs continue to play out in contemporary art circles in Indonesia, the continuous loop of mutually obscuring vision in Restu’s tjap pattern, and the anxious intertwining of the figures projected onto the void of the table cloth pattern, speaks where voices are often silent.

And now…

Earlier this year, I returned to Jogja again to teach with ACICIS. I visited with Nia and Ismoyo, binged on my favourite street foods, cycled the streets and fretted with friends over the impending but inevitable arrival of COVID-19 (or was it already there?). In January I received an email: a local artist working with batik was to exhibit his works in Sydney; would I be interested in writing for the catalogue? I was only vaguely familiar with Dias Prabu’s work and had never met him, but his enormous batik cloths were intriguingly divergent from the works of other artists I knew.

Dias’ adoption of batik came after many years working in painting, making enormous murals for which he received national recognition. In 2018, in residence at Kampung Batik Manding Siberkreasi, a community south of Yogyakarta, Dias worked with children and murals, building his understanding of the ancient patterns and functions of batik, collaboratively designing new symbols, and refining his skills with the canting, which he had briefly encountered in his undergraduate studies.

In his batik works to date, Dias largely eschews the pattern, repetition and abstract symbolism characteristic of the Javanese “tradition”, instead drawing on a menagerie of allegorical animals coupled with text, which he spontaneously inscribes onto long stretches of fabric—a single length of 100 metres filled the main room of his small home when I visited him—with a technique that resembles line drawing more than any of the conventions of the form. Unusually, his work often features symbols of national pride in what he describes as his contribution to the nation.

Dias at home making batik

Since the fall of Suharto’s authoritarian New Order regime in 1998, contemporary artists rarely adopt symbols of loyalty to the nation, unless invoked in kind of cynicism exemplified in the work of groups like Punkasila, a band of artists whose name plays on the five-pillars, or Pancasila, that Indonesia is founded on. Yuliman called the early proponents of this critical art practice, artists like FX Harsono and Moelyono, “the restless ones”, a generation whose sometimes-coded responses were crafted to oppose a government that exploited people and the environment. Now senior artists and mentors to younger generations: their legacy remains influential. By contrast, outside the arts, an average young Indonesian on Instagram might well be declaring their allegiance to the nation on annual Youth Pledge Day. Perhaps Dias’ approach is more reflective of that majority who hold fast to the lessons imparted to them in school and university?

But it would be remiss to assume Dias’ batik lacks criticality. Through his passion for the nation, his work expresses a deep concern that Indonesians have lost touch with the wisdom of their ancestors—a concern shared deeply by Nia and Ismoyo on a more global scale. While ancient batik patterns have been used as talisman to ward off catastrophic events for individuals and society, invoking the three worlds and their inherent interconnection, Dias’ works are instead instinctive outpourings of his personal interpretation of that wisdom, generated through his familial history and his environment.

When I first examined Dias’ work, many cherished familial sites were ablaze, and I wrote, “Dias’ optimistic writing and positive mantras seemed naively cheerful as the globe reaches such a terrifying tipping point…” I questioned whether there was indeed still time to make amends with our environment and recognise the interdependence of our own lives on the lives of our environment.

We had yet to fully reconcile ourselves to the drastic consequences of the Black Summer in Australia, much less the response it demands, when yet another spectre of disaster visited us, this time on an unimaginable global scale. And again it is a calamity of our own making, a consequence of our wilful disordering of our place in the macro-cosmos, a blindness to the potential of the unseen, and the relegation of the relationships of care which are integral to the wholeness of our micro-cosmos.

I ended my ruminations on Dias’ batiked monuments to ancient wisdom by borrowing a phrase from his indigo and white work, Purpose of life, which evokes the Javanese proverb often spoken by his parents: ngunduh wong pekerti, or “you reap what you sow”. I will end with the same note again here, this time with ever more urgency. “Will we choose to respect the practices of elders that safeguarded our existence on this earth for hundreds of thousands of years? Or will we continue our downward spiral of consumption, destruction and oblivion? “Ngunduh wong pekerti.”

Truth be told, I’ve never achieved more than a passive understanding of Javanese, and the deeply spiritual, symbolic and ritualistic nature of batik remains on the other side of a threshold I’ve not yet been able to cross. But thinking of batik as an explorer, as a making process that taps into and deep currents of cosmic universality while simultaneously tracing the ebbs and flows of humankind’s cultural, geographical and political mobility, allows me to embed batik as a constant in my practice. It’s a kind of drawing that, although neither my cultural inheritance nor my spiritual familiar, unlocks a consciousness like no other mark-making.

Author

Dr Elly Kent is the editor of New Mandala and a Visiting Fellow in the Centre for Art History and Art Theory at the Australian National University. She has worked as a researcher, writer, translator, artist, teacher and intercultural professional over 20 years in academia and the arts in Indonesia and Australia, and continues her practice in Canberra where she lives with her family.

Dr Elly Kent is the editor of New Mandala and a Visiting Fellow in the Centre for Art History and Art Theory at the Australian National University. She has worked as a researcher, writer, translator, artist, teacher and intercultural professional over 20 years in academia and the arts in Indonesia and Australia, and continues her practice in Canberra where she lives with her family.