- Yirrkala- this mural depicts artists and leaders including Wandjuk Marika, Mawalan Marika, Roy Dadaynga Marika

The Indigenous Jewellery Project travels to North East Arnhem Land to explore the tradition of Yolŋu jewellery and work with jewellers on a new project.

Bulay(i): rich jewellery, gold, precious stones, bronze treasure (Yolŋu Matha language)

As one of Australia’s most prestigious and internationally recognised Aboriginal-owned art centres, Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka in Yirrkala, the Yolŋu community outside of Nhulunbuy (Gove) in North East Arnhem Land, is well-recognised for both practising and maintaining artistic and cultural tradition and creating exciting innovation with its art.

Its artists have exhibited in many of Australia’s top public and commercial galleries, including as part of the Biennale of Sydney at the MCA, the NGA, AGNSW, NGV, NMA and internationally including the Istanbul Biennial and in the exhibition Marking the Infinite, Newcomb Museum of Art, touring USA.

Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka has long been a leading studio in printmaking, and is world famous for its tradition of bark painting and sculpture, with large commissions including The Kerry Stokes Collection of 95 larrakitj poles and accompanying encyclopedic book.

More recently, these artists have explored new media in their art, working with computer programming and film. The Mulka Project is the centre’s dedicated archival and film project. It is now one of its major forces in working with younger generations full of the artistic genius that seems to spring up everywhere in this historically significant place.

As well as painting, sculpture, new media and printmaking, craft has always been well maintained here. The art centre is a treasure trove of stunning fibre work by Yolŋu women, inventive small wooden carvings and objects and, of course, jewellery. Strands of necklaces called girring-girring in Yolŋu matha, the lingua franca of the region’s many languages, hang in the art centre, delighting visitors who visit in a seemingly endless stream.

The art centre’s proximity to an airport and accommodation at nearby Nhulunbuy, along with its fame for significance in land rights, art, music (home of Yothu Yindi and family with nearby Elcho Island’s Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupiŋgu), the home of the yiḏaki or dhambiḻpiḻ (didgeridoo), and Garma Festival, means that on any given day, one may encounter collectors and gallery directors from America, professors from Canberra, top Australian public gallery curators, important politicians (often a Prime Minister), or famous musicians, actors or artists. This is amidst the constant stream of fascinated tourists visiting for the rich culture, beautiful tropical scenery and world-class fresh seafood that the region has to offer, especially now that Yirrkala boasts a Yolŋu-owned and operated tourism business, Lirrwi Tourism.

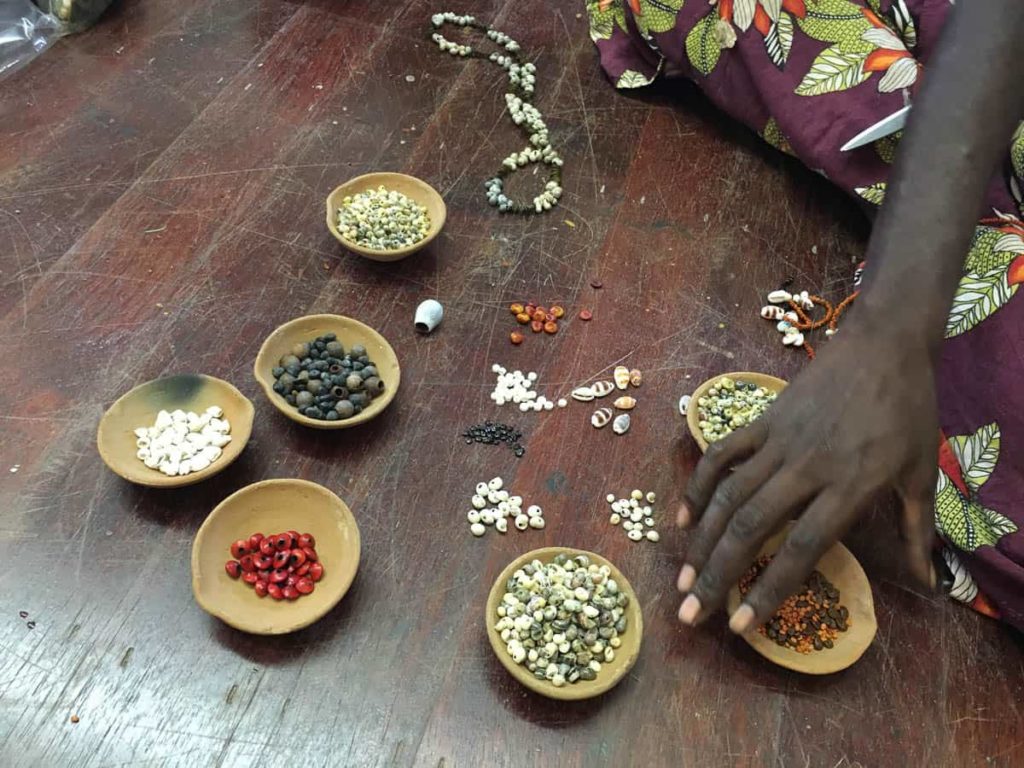

Whilst the jewellery practice from this region, consisting mostly of necklaces strung with extremely fine seed beads, shells and shark vertebrae, has long been noted and admired, appearing in the groundbreaking exhibition Art on a String (Louise Hamby and Diana Young, Object: Australian Design Centre for Craft & Design, 2001), Bulay(i) is the first jewellery-focused project held at Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka, which works with many artists living in Yirrkala and its satellite homelands within a several hundred km radius.

Its aims are to hold workshops that help Yolŋu jewellers upskill and develop their jewellery practice, to help maintain traditional jewellery practice, and to learn new skills such as lost wax and working for the exhibition space. The strength of all Aboriginal art has been the artists’ ability to both maintain their strong traditions whilst innovating their art in ways they see fit. In Yirrkala, there is a strong tradition of bark painting in natural ochre using natural hairbrush. The artist Gunybi Ganambarr has innovated this tradition by using mining offcuts such as metal and rubber. Yet his designs remain strongly traditional. Introducing lost wax for metals and professional jewellers materials for stringing is similar: the artists’ designs are still Yolŋu, but they are using materials which develop their practice.

Working with Sydney-based contemporary jeweller, UNSW lecturer and curator Melinda Young, I have run two workshops here thanks to generous support from the Ministry for the Arts Indigenous Languages and Arts Program. The results will be exhibited later this year at the Australian Design Centre, Sydney, and Craft ACT: Craft and Design Centre, Canberra.

This is a visual diary of the second workshop, held in April/May 2017: which saw jewellers continue to develop their practice and the project grow to encompass over 20 jewellers.

Arrival and set up

Our contemporary jewellery workshop teacher Melinda Young has already arrived, bringing a heap of workshop materials and tools, and began to set up our pop-up workshop studio.

We are lucky enough to be once again given the Collector’s Gallery as our workshop space. This sits at the side of the large art centre, by a courtyard housing a pond with a beloved file snake, a sacred local totem related to the Rainbow Serpent lore, and a large sculpture by Gunybi Ganambarr, who Sydney Morning Herald art critic John McDonald declared a genius and said of a solo exhibition of his at Sydney’s Annandale Galleries: “No artist, not even Picasso, had ever managed to come up with so many revolutionary gestures in the course of a single exhibition”.

In this gallery we are surrounded by large, stunning bark paintings by top contemporary artists such as Nyapanyapa Yunupiŋu, Banduk Marika, Nongirrŋna Marawili, Djirrirra Wunuŋmurra, Dhuwarrwarr Marika, Mulkun Wirrpanda, and a large installation of Mokuy sculptures by a Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award (NATSIAA), New Media Award winner, Nawurapu Wunuŋmurra.

Over our first morning coffee, we are greeted with a striking rainbow over the mural of the land rights leaders that decorates the store near the centre. It depicts artists including Wandjuk Marika, Mawalan Marika and Roy Dadaynga Marika, in full traditional body adornment and jewellery: their image serves as a daily inspiration and motivation for me, a visual reminder of their culture and strength, a spiritual reminder of their persistence. Greeting them becomes the first thing I do each morning. The rainbow, a manifestation of the Rainbow Serpent for Yolŋu, is a good omen, according to our jewellers: it is welcoming us to this special place.

Workshop Day One: Wednesday

- Contemporary Jewellery workshop teacher Melinda Young with her breezeblock artists bench

- Working on lost wax technique in the workshop

- DJ Marika and Melinda Young discuss the stingray ring

- Marrnyula Mununggurr works with Melinda Young on her rings at Galaru

Our first thing to do is get the word out. With one of our jewellers, we go for a drive around the community to visit jewellers and let them know we are here and to come down to the workshop.

We set up our lost wax studio and have the first jewellers in the workshop. Melinda Young makes a surprisingly good jeweller’s bench out of the concrete breezeblocks that are everywhere here (used as presses to flatten out barks for painting). She’s brought back the metals that were made last time for the jewellers to begin to learn the process of cleanup and finishing.

She also has with her a very exciting development, a ring made with BLM young artist Djawakan No.2 (DJ) Marika. The grandson of famed artist and leader Wandjuk Marika, DJ came into the art centre one day wearing a ring made from a stingray he had caught. Called dirimbi, this is a kind of stingray that has rings on its tail. Traditionally, the hunter would wear these rings as a trophy of his catch.

Will Stubbs, BLM’s co-ordinator, sent me a photo of DJ wearing this stingray ring, which I passed onto Mel. With her directions, the ring was put onto wooden lasts and sent to her in Sydney, where she prepared it for casting. Several stingray rings were prepared by her and some initially didn’t work, but then one did.

The results are stunning: the texture of the ring and its tiny horns is tactile and unique. It is the first I have known of a traditional Aboriginal ring. That this Yolŋu men’s tradition may be thousands of years old makes this an exciting discovery in the world of jewellery. We are all very excited about the potential for this ring and think it could have impact internationally. That a young Yolŋu man is continuing this jewellery tradition of his forefathers and the art centre is working to translate it into his contemporary age is symbolic of this art movement; a brilliant blend of strong tradition and innovation.

The ring was entered and accepted into the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award (NATSIAA), the Aboriginal art world’s most significant art award, held at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, to be shown this August.

In our workshop, we are joined by the very established artist Dhuwarrwarr Marika, who has several bark paintings in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. Mel introduces her to lost wax and she makes her first pieces in this medium.

Another elder, Djul’ Djul’ Gurruwiwi, also joins us. One of my favourite artists, our gallery has enjoyed exhibiting her work, beautiful depictions of totemic fish and water lilies. She is also introduced to lost wax and makes several pieces.

A new young jeweller, printmaker and associate director of the BLM Print Space, Rebecca Marika joins us, and instantly impresses us with her skills and feel for lost wax. The strength of these artists’ practice in traditional woodcarving and in printmaking lends itself well to lost wax, as much of it is about carving and etching. She also brings her own tool kit of printmaking tools that Mel discovers work incredibly well for etching into the jeweller’s wax, which is very exciting.

Workshop Day Two: Thursday

- Dhuwarrwarr Marika creating her first pieces in lost wax

- Rebecca Marika working on a turtle small object in lost wax

Dhuwarrwarrr Marika and Rebecca Marika join us again, and we continue with lost wax. As it is the end of the wet season, the seeds that the jewellers picked in our first workshop during the dry season last year aren’t available yet, so we are only working with shells, shark vertebrae, some limited seed beads from last year, and lost wax. It’s a good opportunity for the jewellers to develop their lost wax skills and refine their practice.

Gunybi Ganambarr also visits us, and is fascinated by my dremel toolkit. This artist has single-handedly revolutionised bark painting by using leftover materials from the local mining: large pieces of rubber and tin, which he etches with intricate, beautifully patterned design. I explain to him the lost wax process and he is intrigued. I can envision him working in jewellery: his smaller rubber pieces would make incredible neckpieces and his skill at etching would transfer wonderfully to lost wax. It may be another potential future idea for this creatively rich art centre and our project.

In the afternoon, one of the talented necklace jewellers from the last workshop, Mandy Wanambi, arrives. One of the biggest issues we thought of when we began this project was how to upskill the girring girring made by these jewellers. They are strung on fishing line, which has several issues. In research last year, Melinda Young identified three major problems with the fishing line: gaps, breaking and scratching. These jewellers use these tiny seeds fresh, and as they dry they shrink, creating gaps in the necklace. Fishing line also breaks, and the knots used to tie the necklaces are scratchy and irritating for the wearer.

In our first workshop we brought better quality necklace materials and the jewellers took to it instantly. What has become apparent to me through working with Indigenous jewellers is that no one understands this project and my vision for it better than these jewellers. They skilfully use the materials that are available to them to make jewellery, and are a long distance from the jewellery supply stores in Melbourne and Sydney. Their use of fishing line is not just cultural, but also born out of necessity.

Proper jewellery materials and tools are taken up enthusiastically, and whilst not every idea Mel and I suggest is of interest, the ones that are have great results.

There are still some elements we need to work on, such as knotting. Mel taught the jewellers how to make adjustable knots using seed beads, and but not everyone is interested yet in doing this more fiddly, less creative work. Next workshop we will work on getting better knots, and also teach some of the crucial but less “fun” aspects of lost wax: clean up and finishing. There are several young women who we feel will have the talent and patience for this.

This project has not so much been initiated by me, as is a response to the jewellery practice that already exists. As in the other mediums of art, it takes focus, attention and some assistance to develop this work from where it is situated currently into the exhibition space. The project is not without its challenges. Working remotely, every aspect needs to be carefully planned many months in advance by Mel and I. Aboriginal people have many obligations in their lives, many of which are invisible to us outsiders. Some of the jewellers come and go from the workshops, due to other obligations, or living out on homelands. I am impressed with this group how many are here every day, that we have most of the same jewellers from last year, and that new ones continue to join us.

Another aspect of the girring girring is the importance of helping Yolŋu document and preserve language. Some of the Yolŋu matha words are disappearing from use: jewellers often refer to seed beads as “baked beans” or “coffee seed”. This is an ongoing part of my work in the project: to document and use names in Aboriginal languages as much as possible and create a glossary, and to introduce those names into the lexicon of Australian jewellery to the outside audience.

Day Three: Friday

- Marrnyula Mununggurr with the first of her bark painting neckpiece series

- Marrnyula Mununggurr works on her series of pendants with her mother Nongirrnga Marawili painting behind her

- Marrnyula Mununggurr collects shells on the way to Dhaliwuy Bay

- Marrnyula Mununggurr working on her ring series

- Marrnyula Mununggurr collects shells on the way to Dhaliwuy Bay

Marrnyula Munuŋgurr joins us today. A long-time practicing artist, she has been working with BLM since the 1980s, and has had significant exhibitions and work in Cross Art Projects, Gertrude Contemporary and the NGV.

Marrnyula’s creates installations of often hundreds of small bark paintings, painted finely in ochre with a hairbrush paintbrush with her clan design of crosshatched squares. She begins work on a lost wax series, a collection of rings etched with lines, to be stacked up to recall a larrakitj pole. She then begins work on a series of square pendants in wax with her fine cross-hatched geometric design.

Day Four: Saturday

Beach studio! We decide to go to Galuru, a beach west of Nhulunbuy, with Marrnyula, who takes the rings she’s working on with her. We are joined by some special visitors, Nick Mitzevich, the director of the Art Gallery of South Australia, and Nici Cumpston, AGSA’s Curator of Indigenous Art and the director of TARNANTHI Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal + Torres Strait Islander Art, who are visiting the art centre.

Nick Mitzevich becomes instantly obsessed with DJ and Mel’s stingray ring: and says he never wears jewellery but he wants to wear one immediately!

Nici was The Indigenous Jewellery Project’s first supporter and helped us bring our first exhibition, working with Ernabella Arts and Ikuntji Artists, to the JamFactory, Adelaide, as part of the first TARNANTHI. She enjoys watching Marrnyula making her rings and hearing about the process, and we talk about future ideas for the project with TARNANTHI.

Everyone goes hunting and brings back fresh mussels and oysters, cooked on the campfire, and declares them the best they’ve ever eaten. While Marrnyula and I make rings together, Mel Young goes hunting for shells and other materials along the beautiful beach.

Day Five: Sunday

- Marrnyula Mununggurr collects shells on the way to Dhaliwuy Bay

- Marrnyula Mununggurr collects shells on the way to Dhaliwuy Bay

Sunday is hunting day in Yirrkala, meaning that the art centre staff, family and friends go for a long drive in the troopy to a more remote beach to gather fresh seafood. We all head off in the back of Will’s troopy, with Marrnyula and her sister with us, to Dhaliwuy Bay, a stunning spot popular for fishing and camping, passing the Garma Festival site as we do.

On the way we stop for oysters, and Marrnyula shows me the amount of shells and coral on the sloping cliff down to the rocky beach. We collect all kinds of shells that might be good for necklaces and find an incredible face-like stone.

Day Six: Monday

- Madatjula Robyn Yunupiŋu, Earrings, Silver and seed beads, 2017

- Madatjula Robyn Yunupiŋu in the workshop

The great earring maker Robyn Madatjula Yunupiŋu joins us today. Robyn learnt to make hand-made earring hooks last year from Mel and is now a dedicated expert. She begins work on a new series of silver earrings using this years shell and shark vertebrae beads.

All the other jewellers continue on their lost wax and by the end of the day there is a small mountain of wax shavings on the floor! Mel fears we are running out of the large amount of wax she brought with her, so gets on the phone to order more.

Day Seven: Tuesday

It’s Anzac Day and the art centre’s closed but we all decide to work in the studio while it’s quiet. Lots of work gets done!

Day Eight: Wednesday

Marrnyula and the rest of the jewellers continue with their lost wax series. A particularly talented and dedicated young jeweller, Pamela Yunupiŋu, is making more and more refined lost wax work. She has a talent for the difficult aspects of jewellery: knot tying, the endless filing and sanding down required to get the work fine enough to be light-weight enough in metal to be wearable and soft on the wearer.

Day Nine: Thursday

The end of the wet season is having a final burst of rain, and we have a good group of jewellers inside the studio including new arrivals, as well as bark painters who usually paint in the courtyard outside.

We have also been looking at contemporary jewellery books with the jewellers to show them what is possible in terms of scale and making work, not just for the body but also for the gallery space. In conversation with Marrnyula and Mel, we talk about Marrnyula’s installation at the NGV of 252 small barks and Melinda Young’s wooden neckpieces, and we all think about how to take Marrnyula’s barks onto the body. I enquire about any cultural issues with this and discuss this with Marrnyula, who knows an enormous amount. She says that it has no issues. Bark paintings were originally made on bark shelters, so there are no laws saying you can’t make them for the body just as you could for a wall. Marrnyula immediately makes some small barks and, once strung, the neckpiece looks incredible, both for the body and the wall. She sets about making a series of many of them for exhibition.

Day Ten: Friday

We have so many jewellers now making so much work: we are running out of materials! We beg the art centre for any more broken necklaces they may have, and find any old ones and even resort to buying some to reuse! I clean each seed and shell by hand with a paintbrush for the jewellers to use: I’m happy to be jeweller’s assistant and we need to use our time here as efficiently as we can.

We have some new jewellery talent come in, Marrnyula’s cousin, Yirrinyina #2 Yunupiŋu Maḏinydjarr nee Munuŋgurr, whose an exemplary necklace jeweller, working with shark vertebrae and parrot fish bone, and her two daughters, who are equally talented jewellers.

Day Eleven: Saturday

- Drying the ḻuthuḻuthu- shells for beads

- Bulay(i) Project workshop 2017

- Seed beads and shark cartilage beads

- Seed beads ready for stringing

- Pamela Yunupiŋu Marrawaymala, Girring Girring (Necklace), Seed beads and shell beads on polyester thread, 2017

- Madatjula Robyn Yunupiŋu, Earrings, Silver and seed beads, 2017

Mel and I have a meeting with Will (Will Stubbs, manager of the Buka art centre) in the morning to have a look at all the work and see how things are progressing. We discuss some of the designs that are culturally sensitive under Yolŋu law; anything he sees as problematic we pull out of the future exhibition works. We also choose to run editions of any exemplary works that are good enough to have moulds made of. One of the good things about jewellery is that as in printmaking, one can make editions of pieces and distribute them to galleries widely. Will is happy with the work and gives us some beautiful traditional feather armbands from the art centre to put in the exhibition. Mel suggests also including a spindle she saw, hand-made with soft bush string wrapped around it. These will provide important historical cultural context to the show at the Australian Design Centre.

We have heard from our jewellers that there are good shells to be found at Lombuy (Crocodile Creek), another beach not far from Nhulunbuy (I wonder if good shell locations are kept secret, like rare pink ochre often is across Aboriginal Australia, as my gentle enquiries about shell locations have not had a huge response so far…). In the afternoon we head there with Marrnyula, her sister Rerrkirrwanga Munuŋgurr and family. Rerrkirrwanga heads off into the mangroves, I am reticent to follow her, mangroves being the home of bäru, crocodiles. After quite some time she returns with a bag of the tiny shells, called ḻuthuḻuthu in Yolŋu Matha. We wash them with water from the billy on the campfire, and the sisters and Mel set about cleaning them and I take them home to clean again and dry out in the sun ready for Monday.

Last Days

Mel leaves us for Sydney Monday morning, and it’s May Day, a public holiday in the Northern Territory. The jewellers have seized the opportunity to go hunting for fresh bush tucker with their families, so it’s just Marrnyula and I in the studio. She continues work on her bark painting neckpieces and decides to make a large series of fifty! They will be stunning with her metal versions in the exhibition and to wear.

Mel leaves us for Sydney Monday morning, and it’s May Day, a public holiday in the Northern Territory. The jewellers have seized the opportunity to go hunting for fresh bush tucker with their families, so it’s just Marrnyula and I in the studio. She continues work on her bark painting neckpieces and decides to make a large series of fifty! They will be stunning with her metal versions in the exhibition and to wear.

Mel leaves us for Sydney Monday morning, and it’s May Day, a public holiday in the Northern Territory. The jewellers have seized the opportunity to go hunting for fresh bush tucker with their families, so it’s just Marrnyula and I in the studio. She continues work on her bark painting neckpieces and decides to make a large series of fifty! They will be stunning with her metal versions in the exhibition and to wear.

Our last day sees a big group of jewellers with still new ones coming in! Everybody is relaxed and focused now, huge amounts of wax gets made, and I have to finally wind everyone up to pack up all the work made, and the tools and materials and work for next time.

With last year’s and this year’s workshop, I count how many jewellers we have: at least 23! They have made well over two hundred works and we plan to come back for our third workshop at the end of June to work further on the jewellers’ techniques, and on putting the cast metal pieces together with the shark, shell and seed necklaces to make some really stunning exhibition work.

Bulay(i): Contemporary Yolŋu Jewellery will show at Australian Design Centre, Sydney, 19 October – 15 November 2017 and DESIGN Canberra, Craft ACT, Canberra, 7 – 26 November 2017

Author

Emily McCulloch Childs is an art historian & writer, curator, gallery director, publisher and researcher. She specialises in Indigenous art, and has worked with Aboriginal art and artists since 1994. She is co-director, with her mother Susan McCulloch, of McCulloch & McCulloch, a multi-faceted art company, and Whistlewood Gallery, on the Mornington Peninsula, the co-author of McCulloch’s Encyclopedia of Australian Art and McCulloch’s Contemporary Aboriginal Art, and is the founding curator of The Indigenous Jewellery Project. She lives on the Mornington Peninsula, Victoria.

Comments

Thank you very much for this very interesting and detailed insight to your jewellery workshop. It is wonderful to see how the Aboriginal people work and create jewellery. I woud love to see more of their creations. Will there be a documentation (catalogue) for your exhibtion?

With my very best regards and congratulations to the artists

Martina Dempf

Jewellery artist and anthropolgist

http://www.martina-dempf.de

What a wonderful article, thank you for sharing. The location and landscape descriptions have me enticed, a new place to put on my list to get to. Your enthusiasm for the project, its participants and care for that work to be well made shine through. can’t wait to handle a stingray ring! I hope you can bring this show to Melbourne. Vicki Mason

Brilliant project – thanks for sharing so much detail and great photos. Congratulations DJ on the ring design, and to all the participants for their wonderful work. Hope the exhibition comes to Melbourne.