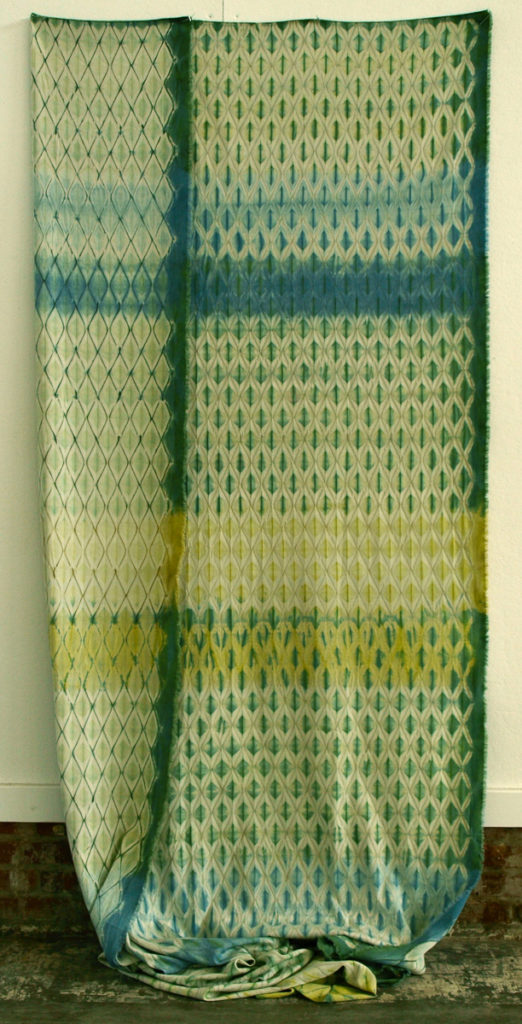

- Catharine Ellis, Garden series, weld

- Catharine Ellis, cotton, Jacquard woven shibori, dyed with natural plant dyes. 60″ x 108″

- Yellow + Blue = Green, detail photo by artist

We feature weld-dyer Catharine Ellis, from the book True Colors, by Keith Recker who reflects on the principles that underlie his life in colour, thus far.

(A message to the reader.)

My first introduction to natural dyes was “during my year on the Navajo reservation in Arizona, where I was a student at the Navajo Community College. We gathered alum right from the ground. Leaves, alum, and wool were all put in a pot together and cooked,” Catharine Ellis recounts, but information on natural dyes and the best techniques to achieve beautiful colors was superficial.

There was no science to it, and plenty of misinformation. Can dandelion roots give you red, as the first book on natural dyes I bought said they would? No, they can’t.

Natural dyes were not especially exciting to Catharine at that point. “Eventually, I got tired of all the yellows and beiges I was getting from the plants around me,” she recalls. “I felt I had to become more professional—to master synthetic dyes. I enjoyed the discipline and the science and the specificity of working this way, and I became very adept at using acid dyes, fiber-reactive dyes, and more.” Beyond her expertise in dyeing, Catharine developed what she calls “woven shibori,” which involves adding supplementary threads to a textile on the loom and using them to gather and shape a cloth during the shibori process. Catharine shared her passion for weaving and dyeing over a long career as a teacher, and it was, in part, her students who asked for her to return to natural color. But it was retirement from teaching in 2008 that brought her fully back to natural dyestuffs. “When I set up my studio at home, where we have a well and a septic system and a creek, I knew that I couldn’t continue using the chemical dyes that were my forte. I had to explore more natural ways of working.”

Ever committed to mastering whatever discipline she pursues, Catharine went to an expert in her search for natural-dye knowledge. Michel Garcia, a French citizen born in Algeria, is renowned worldwide for his careful and artful exploration of historical natural dyes and printing techniques and for his generous workshops. “He showed us cottons printed and dyed in brilliant colors with natural dyes and hinted at a body of information I did not know. Michel showed me it could be done, which pushed me to go home and test, test, test! But I admit that I was still confused.”

The confusion began to settle in 1997 when Catharine met Joy Boutrup at the Penland School of Crafts in North Carolina, where she was teaching technical aspects of printing and textile finishing. Joy’s technical expertise, developed since the 1970s when she earned a textile degree in Germany, centers on the study of historical textiles, particularly early twentieth-century commercial work produced when natural components were still in use.“ Joy became my teacher. She’s a linear thinker who knows how to explain process and science. She will often hint at the ‘why’ behind a dye phenomenon or at an historical solution to a color challenge, and off I go to test it out in the studio.”

Their working partnership resulted in the 2019 publication The Art and Science of Natural Dyes: Principles, Experiments, and Results, which explains the scientific principles of natural dyeing and goes deep into hundreds of combinations of dyestuff, mordant, time, temperature, and other variables.

What is Catharine’s favorite natural dyestuff? “Weld is the rock star flavonol of the natural dye world,” she answers with surety. “Based on everything I have observed, it produces the clearest, most lightfast yellow of the commonly available natural dyestuffs.”

The stems, leaves, and flowers of weld, known botanically as Reseda luteola and commonly as Dyer’s Rocket, contain luteolin, a flavonol compound that yields yellow color. This biennial grows up to five feet high, with spikes of pale yellow flowers blooming in June. Archaeological evidence shows that weld has been used to make yellow dyes since at least 1000 BC. Traditionally employed to color silks and wools, weld can also be used in the production of lake pigments (with the addition of alum or calcium). Dutch master Johannes Vermeer evidently used weld-derived paints in his Girl with a Pearl Earring.

“I bought weld only once, from Maiwa in Vancouver,” says Catharine. “Then I started to grow it on my own. There’s always a patch of it in the garden now, big enough to do dye work, share with students, and produce seeds for the following year. It keeps indefinitely when dried. It smells good. It’s easy to grow. It likes poor soil, and it seeds itself readily.”

The key to successful weld dyeing, she says, is hard water. “I once tried to dye some wool with weld and got almost no color. The yarn might have been processed with an acid, which is sometimes used to remove plant debris from the raw wool. Once I added chalk to the dye bath, the color simply blossomed.”

These days, Catharine can be found in her studio, dyeing with plants, weaving, and always experimenting toward mastery of something new.

This is an extract from Keith Recker, True Colors: World Masters of Natural Dyes and Pigments, Thrums Books

Interview with Keith Recker

The author of True Colors has helped develop many initaitives in the craft field, particularly through the magazine HAND/EYE. We’re curious to learn about Keth Recker’s view of the world.

✿ What are the values that underlie your long-term interest in natural dyes?

My interest in art, craft and design came into focus when I met Clare Brett Smith, just shy of 30 years ago. She was then president of Aid to Artisans (ATA), an NGO devoted to linking talented artisans to new markets. For her, it was a given that artisans could succeed in any context not just because of their expertise with materials and methods of making, but because of the culture and personality they brought to their work.

The signs of individuality and personality that made each object slightly different were not flaws but virtues. The communication between cultures and people that can come out of an exchange of craft is capable of linking us more deeply with each other, and in a way rich with learning and mutual respect.

My interest in natural color came into focus through Michele Wipplinger, a talented natural dyer and teacher based in the Seattle area. We met through Clare, and Michele proclaimed confidently in our first conversation that she could make any color I could possibly want using only natural substances. She brought cases of sample yarns to my office not long after and, of course, I fell in love with not just the colors, but Michele’s knowledge of the dyestuffs, of the families and communities she was working with, of the ways these materials could be manipulated and combined so effectively. These two people opened up whole worlds of knowledge that was based on personal relationships and on respect for the expertise, acumen and culture of talented people—and of the possibility of lower impact, lower infrastructure, more satisfying ways of making, and of living with what is made in these contexts.

✿ Can you give an example of the use of natural dyes in a mass-produced item?

When the ingredient lists of lipsticks and certain juices, jellies and other foods, contain the words Carminic acid or Natural red #4 or E120, we are in the presence of the cochineal insect, domesticated in Mexico over 2,000 years ago and part of global commerce shortly after the arrival of the Spanish. It is still used today because it does no harm to human health, in notable contrast with some of the synthetic red colorants pursued by manufacturers over the years.

✿ Are there circumstances where synthetics are a better option?

In this complex world, it’s hard to think of one-size-fits-all solutions. We are in a watershed moment, where we need to think multi-dimensionally about the health of the planet, the health of our fellow humans, as well as the subtler matter of well-being and happiness. In a moment like this, deploying all the tools we have available—with forethought and care—seems wise. At the same time, we would do well to revive the knowledge of natural colors that runs so deeply in our history as a species. Because we’ve done our collective “best” to forget this knowledge in the 160+ years since the invention of synthetic dyes, we have work to do to fully understand the potential of plants and animals to yield not just color but frequently medicine and inner satisfaction.

✿ Is knowledge about natural dyes always open source? Are there circumstances where recipes are kept secret and only used by a restricted number of people?

My friend Jenny Balfour-Paul, author of some very good books on indigo, commented to me recently that the world of natural dyes has always seemed to her characterized by a generous sharing of knowledge. My own experience supports that conclusion. Most of the people profiled in True Colors teach their craft to students of all ages. At least two publish books about their craft.

Why the generosity? I think some of it comes from the nature of natural dyeing. From the mineral content of water, which can vary greatly from one place to another, to the metal of the vessel used in the dyeing, to the season in which plant matter is harvested, to the characteristics and preparation of the fiber to be dyed, to the temperature and duration of the immersion in the dye pot, the variables all along the way to the final product can create nuances great and small. Whatever one learns from a teacher or colleague often needs to be explored again in one’s own place of making, and almost inevitably a personality emerges. Add to that the many and varied ways in which dyed yarns or textiles are manipulated and combined, and the possibilities seem infinite.

With new attention being paid to natural dyeing, some shifts in that spirit of generosity seem to be appearing, but it still feels like a warm community.

✿ To what extent is the market critical to the sustainability of crafts? Do you think that government has a role to play?

This is a BIG question that merits long conversation! But, in a nutshell: The presence of a market for crafts does indeed matter. If makers are unable to support themselves, it’s very hard to imagine how craft forms survive. The receptivity to craft in the marketplace has grown in recent years, and has created new opportunities for makers, as well as necessary and overdue exploration of the needs and rights of everyone on the chain from maker to customer. I think translating the best of these ongoing explorations into policy is where government has the most potential to be of service to the handmade world.

✿ Can you nominate a particularly inspiring example of a craft revival?

The post-Soviet revival of traditional textiles in Uzbekistan continues to impress me. After decades of suppression, ikat has roared back into popularity within the country as a symbol of culture. Yes, it’s popular with visitors, and it’s had a good run with international designers, but the value and visibility of the fabric within the country clearly supports the work and fuels creativity.

✿ What are your future plans for HAND/EYE magazine?

I have to say that we are going to stop publishing regularly at the end of the year. I have not shared this publicly, but it is true. The goal, since 2006, has been to tell the stories of artists, artisans and designers working in a craft context without regard for the traditional academic separation of these disciplines, without the traditional hierarchies, and with a truly global sense of inclusivity. Over the years, I’ve seen that our work has made a difference by connecting makers to new markets, by bringing a broader understanding of the value of the handmade, and by serving as a source for journalists and researchers and merchants. In fulfilling our mission, we made a difference. Artists that HAND/EYE was the first to cover now appear in the New York Times and in other major international media. The cause we embraced is now embraced by many—something to be celebrated. But the math of the publishing business is not kind, to say the least, and the time has come to let it go a bit.

Author

Writer, colorist, and artisan activist Keith Recker has for almost 30 years worked with makers from several dozen countries to tell their stories, find new customers, sell their product, and gain the recognition they so deeply deserve. Along the way, he was an executive at Saks Fifth Avenue, Gump’s San Francisco, and Bloomingdale’s; founded HAND/EYE Magazine; led Aid to Artisans; served on several arts and culture boards, wrote three books, and worked with the world’s foremost providers of color intelligence. From his home in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he is currently pro bono Creative Director of the International Folk Art Market, Editor in Chief of TABLE Magazine, and Senior Consultant at the Pantone Color Institute.

Writer, colorist, and artisan activist Keith Recker has for almost 30 years worked with makers from several dozen countries to tell their stories, find new customers, sell their product, and gain the recognition they so deeply deserve. Along the way, he was an executive at Saks Fifth Avenue, Gump’s San Francisco, and Bloomingdale’s; founded HAND/EYE Magazine; led Aid to Artisans; served on several arts and culture boards, wrote three books, and worked with the world’s foremost providers of color intelligence. From his home in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he is currently pro bono Creative Director of the International Folk Art Market, Editor in Chief of TABLE Magazine, and Senior Consultant at the Pantone Color Institute.

Comments

Nice information! Thanks for this article

Great share! This post is very useful.