As a child, I was surrounded by striking ceramics and fine textile motifs from Peru, courtesy of my parents. Depictions of flying warriors, suns bearing faces and birds adorned the walls as kindred spirits. I now collect Peruvian textiles and other handicrafts to arrange in a communal space that inspires contemplation, conversation and creativity, including my own artwork.

Recently, while on a trip to Mexico, I was enthralled by the connective power of handcrafted objects in Claudia Fernandez’s exhibition Ceremonia. Based on a selection of traditional Mexican handicrafts with contextual texts, the works were presented as formal installations. The exhibition focused on the relationship between specialised crafts and the geographic areas their makers had inhabited for hundreds of years. We are shown an ecology of materials that embody a flow between mind and land distributed through objects. Myriad installations crystalize into a survey of the historical agency of Mexican artisans and their connection to landscape.

Fernandez’s practice oscillates between that of an artist who circulates objects and a curator who heals the wound modernity inflicted on hand-made creations. The word curator is from the Latin curare, which means to take care, heal, remediate, improve or correct. Fernandez is an artist who nurtures artists, who takes care and is a partner to the artist.

Mercedes Nasta, an enthusiastic and articulate education officer, took me through the show, explaining that in Fernandez’s formative years her weekends were spent with her parents, both avid collectors, in pursuit of specific Mexican handicrafts in the local sierra.

For Fernandez, art is an alchemic weaving of objects. To walk through these magic spaces is to witness their continual becoming, circulation and enmeshing into the world. For instance, Fernandez sourced wool skirts from the town of San Juan Chamula in Chiapas, traditionally a land of the Zapatistas and culturally a spiritual fusion of Catholicism and Mayan faith known for its unique shamanistic rituals. Here the men weave big heavy black skirts from coarse goats’ wool dyed with natural pigments, and brush it into a rough texture. Fernandez unpicked the skirts and sewed them together into a massive shaggy patchwork that now hangs as a monumental black square. The notion of ceremony here takes on an aesthetic dimension.

- Wool skirts, Chiapas

- Gaban 2009, Josefina Cervantes Salas, Naturally dyed wool woven in foot pedal loom, Vista Hermosa ,Veracruz; Jorongo 2010, Oliva Hernandez Pacheco; Naturally dyed wool woven in waistband loom, Tlaquilpa, Veracruz; Ceremonial Huipil tzotzil black wool with grey stripe 2000, Rosa Gomez Perez, Wool woven in waistband loom, San Juan Charmula, Chiapas

- Sarapes, ponchos and shawls, Oaxaca, Michoacan, Jalisco, Edo. Mexico, Chiapas

In the same room, black and white shawls, blankets and ponchos are displayed along the wall as flat panels. Textiles from Oaxaca are richest, where production rates of the labour-intensive craft are high thanks to the legendary Remigio Mestas Revilla who revived some lost traditions and re-enlivened others that were in danger of becoming obsolete. Antique geometric designs are drawn from the Mitla and Monte Alban pyramids, Mercedes explains, yet they resemble patterns from all around the world. These convergent threads suggest that geometric motifs are forever eccentric and old, an embodiment of communal spirit.

In Ceremonia, tangible products are often the result of Fernandez’s efforts to re-enliven traditional practices that accentuate the materiality of the physical world. The works are outcomes of social projects she has initiated within communities that are losing traditional artistic knowledge and skills. By supplying materials and the knowledge and motivation to create again, Fernandez connects with artisans to reactivate tradition and enable the reproduction of threatened Mesoamerican designs. Together, they enact new strategies to protect and preserve the knowledge of the past and keep it sacrosanct. As such, Ceremonia demonstrates how ideas of community and social exchange may be transformed into a primarily aesthetic investigation involving anthropology and play. In reviving the ways in which traditional handicrafts are made, she creates a pedagogical space, rich in material knowledge.

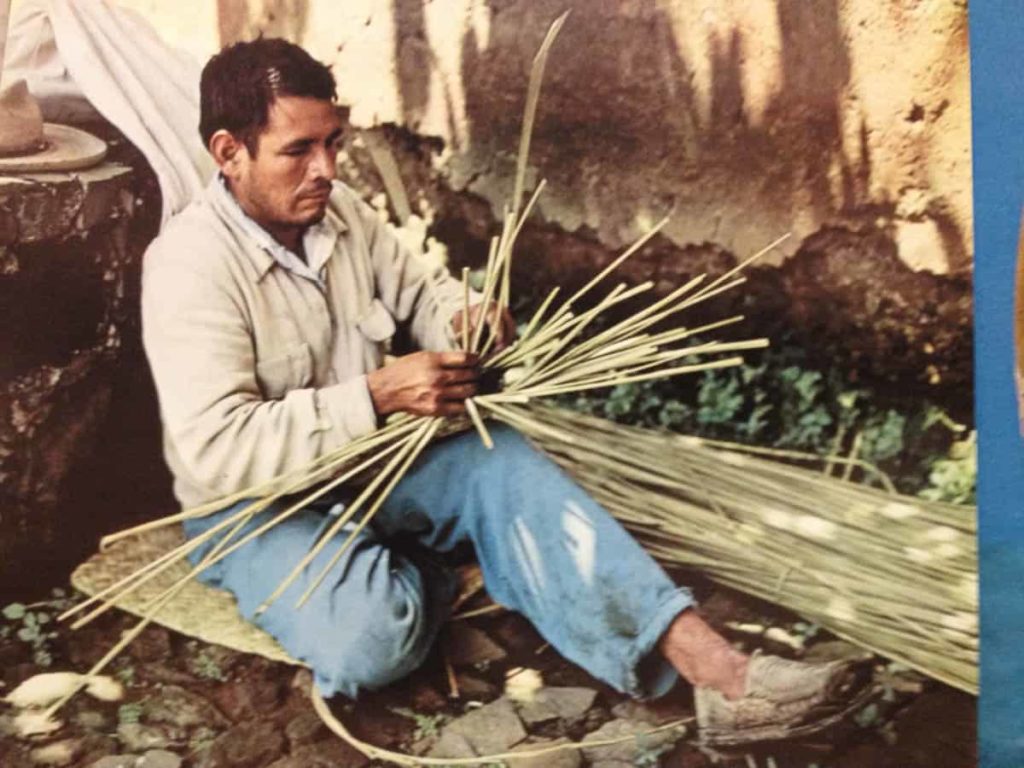

- Painted map, reed tables and chairs, books, ethnographic photos, woven reed items

- ethnographic photograph

- Hand-carved arms, Nuevo san Juan Parangaricutiro, Michoacan

At the entry to the exhibition, a seating area features books describing various artisan crafts positioned before a large hand-painted map of Mexico showing the diverse locations in which the handicrafts are created. Alongside is a wall displaying an archive of ethnographic images from the book The ephemeral and the eternal of popular Mexican art (1974), which is flanked by a constellation of different reed weavings from the artist’s personal collection. Figurative or abstract they appear as emergent forms rather than predetermined. In contrast, Mercedes explains that the very comfortable-looking tables and chairs—also of woven reed—embody a practice that is pre-Columbian and pre-Hispanic. The weaving process was recorded in codex, now almost extinct but which Fernandez remembers seeing as a child. Here aesthetic yet utilitarian objects of everyday living from the past are brought back to life within the present. As the technique involves the gentle removal of palm leaves so as not to kill the tree, the reinvigoration of this almost extinct tradition represents an environmentally sustainable practice that may now continue into the future.

With the handmade as the central theme of the exhibition, a pair of vintage hand-carved mannequin arms—purchased from a market in Michoacan—features prominently on the entry wall to an early room. The magic of the hands scintillates with the pulse of their maker. The wood from which they are carved is sourced from the forest town of Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro, Michoacán, and signifies the now almost redundant practice of using quality materials with a view to creating objects that last forever. The indigenous inhabitants of this town won a United Nations Development Programme award, the $30,000 Equator prize, for their “outstanding achievement in the reduction of poverty through the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity”.

The immanent intersection of natural resources and form mediates a psychic dimension. To emphasise aesthetic practice that is led by the hand, orchestrated by tools, and results in what one’s hands have done is to value the tactile humanist spirit that runs contrary to the economically rationalised mass-produced objects typical of consumer culture today.

- Blown glass, Corretones Workshop, Mexico City

- Coastal ceramics, Tiltepec, Oaxaca

- Sandals, Cisneros Workshop, Concepción de Buenos Aires, Jalisco

- Hand puppets

- Sarapes, Saltillo; Collection of hats

- Wooden washing containers, Patzcuaro, Michoacan

- Painted paper lanterns, La Zamorana Marvels Shop, Mexico City

- Yarn dyed with natural pigments

Vessels glimmer and shine along smoke-marked walls. They appear to have evolved from an aesthetic reserve lying in potentia in the earth. Piles of coloured yarns make up a floor installation: yarns exquisitely dyed with natural pigments such as carmine, moss green and a bright yellow derived from the Cempazuchitl “flower of the dead”, a flower so bright it is placed on altars to guide spirits on the nationally celebrated Day of the Dead. A similarly vibrant display presents painted tables, chairs and wooden trays, bateas, in a small black-painted room. The items are from the town of Michoacan Patzcuaro, where flowers are cultivated—also for the Day of the Dead. The coloured flowers painted on black grounds emanate an appealing auratic glow, an aesthetic repeated in a nearby room filled with multi-coloured paper lanterns, suspended and glowing. The lanterns entice the viewer in with their intricate detail and delicate hand-painted and pressed surfaces. Together, these objects tell the histories of their materials: of materials and humans in a symbiotic agency. Fernandez’s project relishes in the different crafts that continue to thrive despite mass-production. Faces embedded in these loaves of bread remind me of ancient protean forms. Could they be a panacea to modern capitalism’s wound?

- Collection of bread

- Collection of bread

Further reading

Ingold, T 2013, Rethinking the animate, re-animating thought, Espaço Ameríndio, Vol 7, Iss 2 (2013), no. 2.

Ingold, T 2012, Toward an Ecology of Materials, Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 427-442.

McLean, I 2016, Rattling spears : a history of indigenous Australian art, London Reaktion Books, 2016.

Author

Madeleine Kelly is a visual artist living in Wollongong. Her creative work explores the materiality of images, in particular painting, by depicting protean and rubric worlds. Her work can be found at www.madeleinekelly.com.au.

Madeleine Kelly is a visual artist living in Wollongong. Her creative work explores the materiality of images, in particular painting, by depicting protean and rubric worlds. Her work can be found at www.madeleinekelly.com.au.