Constanza Urrutia Wegmann draws on a traditional Inca textile pattern to create a mesmerising weaving.

A textile wrapped, covers, contains and communicates. It is a receptacle of traces, stories and culture. In the land where I live, the most sophisticated textiles are carried by women heirs to the textile tradition of the pre-Hispanic Andes, where they carry their children and move objects. Rolled up on their backs, they alter the contour of their silhouettes and transform their clothed bodies to become the support of their own memory.

In the museums of my city, textile pieces from distant and not so distant times are preserved.

A year ago, the Museo de Arte Popular Americano Tomas Lago, MAPA, belonging to the Universidad de Chile, invited me to generate dialogues between my particular practice as a weaving artist and a piece from its textile collection.

To do this, we spent several afternoons in the museum’s warehouses, on the third floor of an old house in an old neighbourhood of Santiago, where we unwrapped textiles and unfolded woven surfaces, observing and learning how each stitch, structure, material, composition, light and colour spoke of the local identity of those pieces.

Those were moments of encounter. They contained the emotion of the discovery, the smell of the fabrics flooded the place, there was silence and our movements had to be meticulous and careful. You felt time in those textiles.

- Huincha. Charazani, Departamento de La Paz, Bolivia. Ca. 1943. Algodón y mostacillas. Weaving band. Charazani. Department La Paz, Bolivia.Ca. 1943 , cotton and bead.; photo courtesy: Museo de Arte Popular Americano Tomás Lago (MAPA), Facultad de Artes, Universidad de Chile.

- Huincha. Charazani, Departamento de La Paz, Bolivia. Ca. 1943. Algodón y mostacillas. Weaving band. Charazani. Department La Paz, Bolivia.Ca. 1943 , cotton and bead.; photo courtesy: Museo de Arte Popular Americano Tomás Lago (MAPA), Facultad de Artes, Universidad de Chile.

In this “dialogue” proposed by the museum, I came across a small woven band, from 1964, from the town of Charazani, Bolivia.

My work, up to that moment, revolved around the history of textiles produced in manufacturing spaces of modern Chile, where weavers and workers changed the course of political and social history, mobilized by the idea of projecting a fair country. This was related to my own family history and my interest in those textile workspaces, within the large industries.

La Fábrica art project, which fixed that time and its memory, as well as the workspaces and their obsolescence, was tackling different stages and was made up of various pieces and fabrics.

As the investigation progressed, more and more, I noticed small stories, the tiniest ones—those that go unnoticed in official history. I was in search of those that I considered tiny resistances, but that had the quality of containing a trace of truth and that when articulated with others, they are generating great events.

This observation led to a focus on the structural condition of a textile, where thin threads interwoven with others, form a ductile and firm surface, but if they are isolated and seen separately, they do not reveal their potential.

In my encounter with the Charazani band, that perspective echoed again. I observed a small fragment of textile, which did not exceed 40 cm. long, and 6.5 cm. wide. It could contain the journey made by men and women and be the result of exquisite textile technologies, a fusion of Andean Aymara and Quechua culture, which uniquely housed their memory and notion of the world.

Opening the conversation with this piece, I remember the words of a great Quechua weaver. She said that surfaces are deceiving and she spoke of how the textile object has a condition of being alive, as it is built from the material that comes from the earth (cotton, alpaca wool or llama) and the action of the weaver, urging us to try to understand the articulations between the different parts of its structure, inviting us to pay attention precisely to what is invisible to the eye and what lives within the material organisation of a textile.

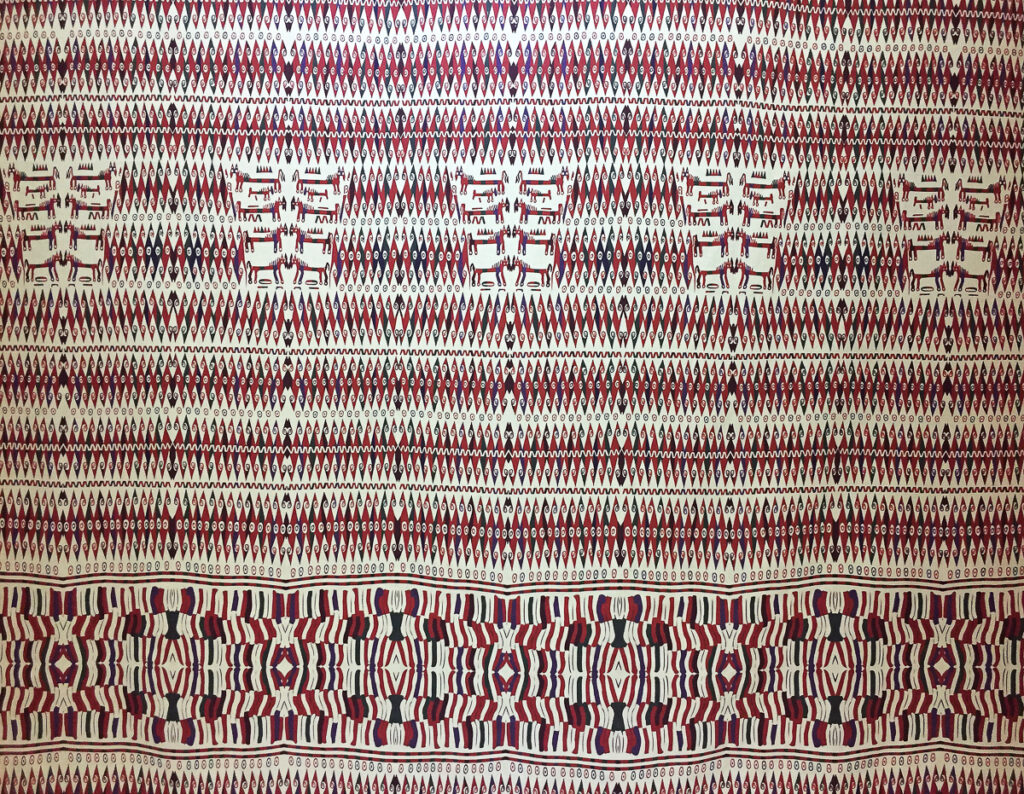

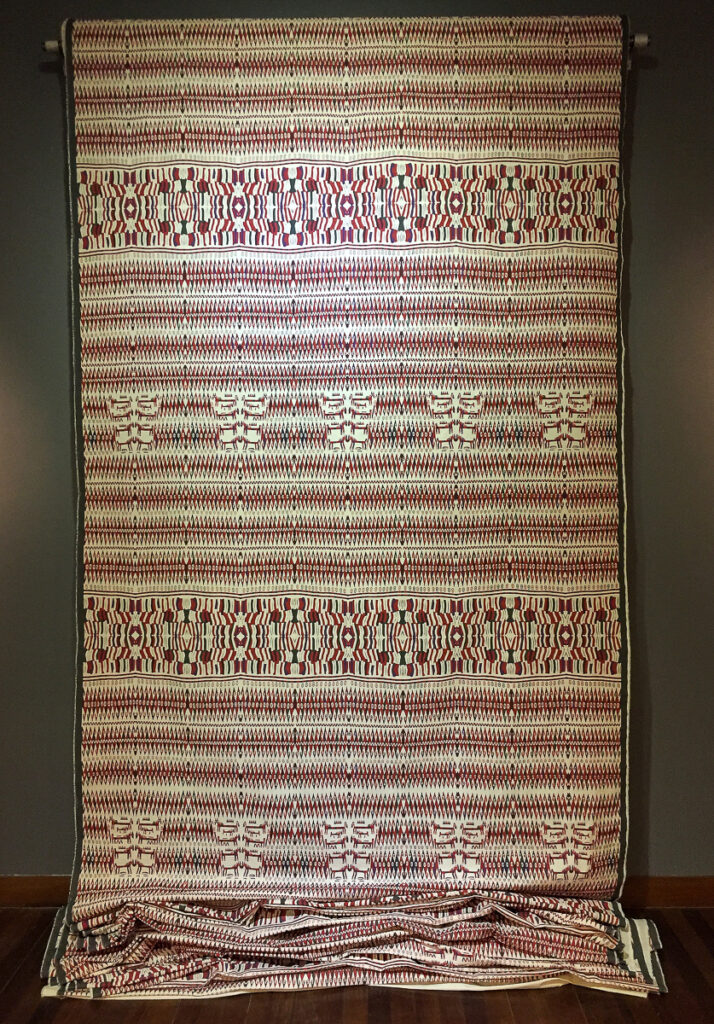

- Constanza Urrutia Wegmann, Charazani . detail

- Constanza Urrutia Wegmann, Charazani weaving

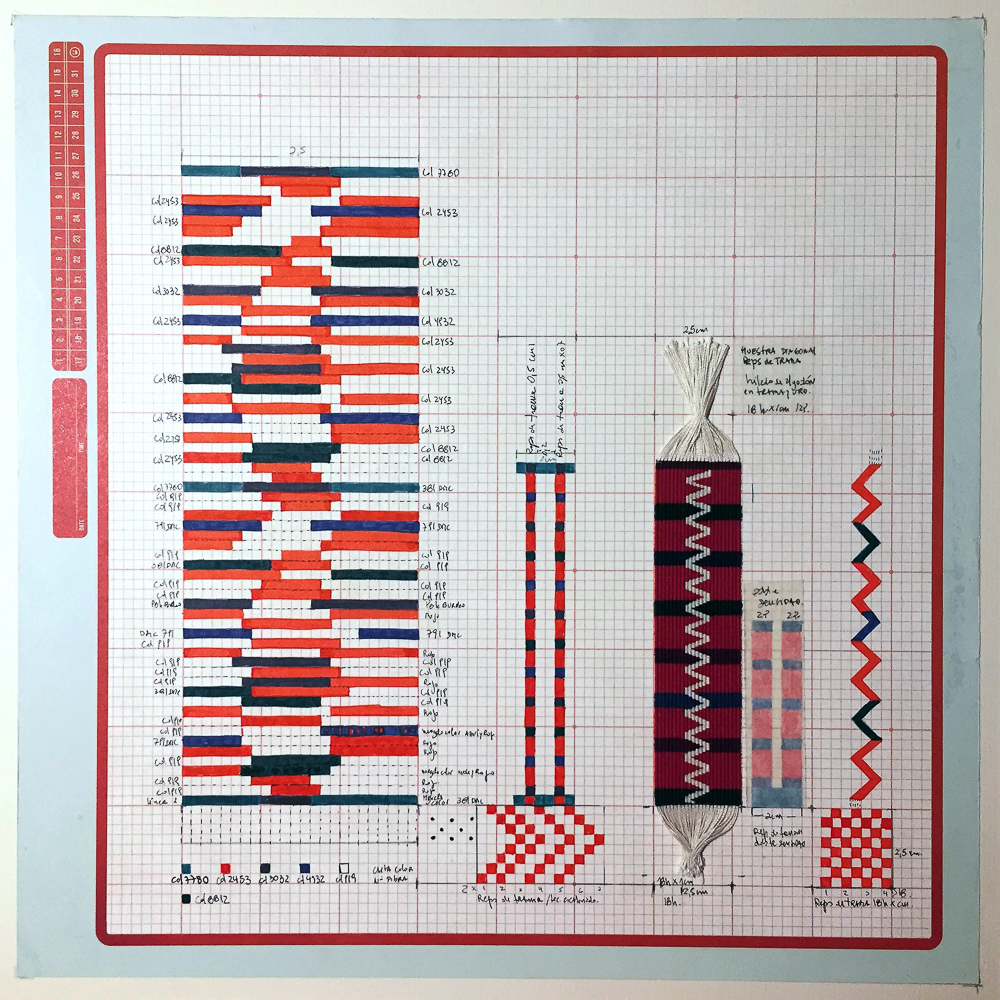

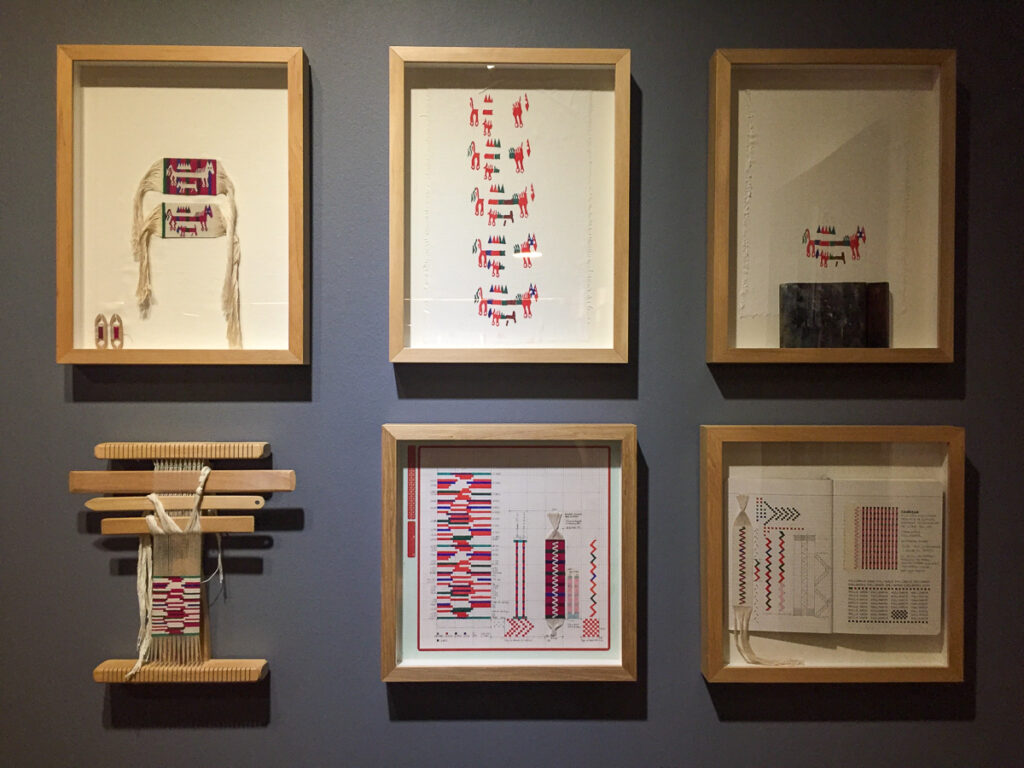

Considering and learning from this small textile piece, I began a contextual study. I did it in the most humble way possible, breaking down its elements, variations and possibilities, approaching, through this woven band, the ancient Kallawaya cultural region, located between the Andes and the Bolivian jungle. Those in charge of providing medicine in the Inca empire descend from the Kallawaya, lands in which curative knowledge is still guarded, which includes human actions with the environment, herbalism, food and, by the way, textile production.

The Charazani project then became an investigation that led me to walk through the possibilities of textile technology that was contained in that small woven band. I walked through the Andean heritage of weaving, listening and insisting on its colors and rhythms, thus as in Charazani’s compositions of keys and horses. Using the principle of the module, I used repetition, making movements towards silkscreen and large extensions printed with the iconography projected by the Kallawaya imaginary.

I listened in silence to the rhythms of my loom in this encounter with the cultures of my territory. I wove colors and stripes, I wove keys and horses, I transferred what I saw onto fabric. I like to imagine that I wove a bridge between what I am and the great weavers of the lands in which I live. The sounds of my warps echoed that story, helping me to remember my own heritage, helping to understand our tiny existences and the brief space one occupies in the world.

Author

I live in Santiago, Chile, and teach textile arts at the Department of Fine Arts, College of Arts, University of Chile. I am also in my final year of a Master’s degree in Fine Arts. Las Fábricas (The Factories) is my graduation project for the degree, including a written text and a number of visual art pieces, among them Machasa Action and The Last Metres.

I live in Santiago, Chile, and teach textile arts at the Department of Fine Arts, College of Arts, University of Chile. I am also in my final year of a Master’s degree in Fine Arts. Las Fábricas (The Factories) is my graduation project for the degree, including a written text and a number of visual art pieces, among them Machasa Action and The Last Metres.

Un textil envuelve, cubre, contiene y comunica, es receptáculo de huellas, historias y cultura. En el territorio que yo habito los textiles más sofisticados los llevan mujeres herederas de la tradición textil de los andes prehispánicos, en ellos portan a sus hijos y trasladan objetos. Enrollados en sus espaldas, alteran el contorno de sus siluetas y transformán sus cuerpos vestidos para convertirse en el soporte de su propia memoria.

Desde otro lugar, en los museos de mi ciudad, se conservan piezas textiles de tiempos lejanos y no tan lejanos.

Hace un año el museo de Arte Popular Americano Tomas Lago, un museo universitario perteneciente a la Universidad de Chile, me invitó a generar diálogos entre mi práctica particular de artista tejedora y alguna pieza de su colección textil.

Para esto pasamos varias tardes en los depósitos del museo, en el tercer piso de una vieja casa de un antiguo barrio de Santiago, donde Desenvolvimos envolturas y desplegamos superficies tejidas, observando y aprendiendo cómo cada puntada, estructura, materialidad, composición, luz y color, hablaba de la identidad local de esas piezas.

(Aquellos fueron momentos de encuentro, contenían la emoción del hallazgo, el olor de los tejidos inundaba el lugar, había silencio y nuestros movimientos debían ser meticulosos y cuidados. Se sentía el tiempo en esos textiles, ese de haber sobrevivido a su propio tiempo).

En este “diálogo” propuesto por el museo, me topé con una pequeña huincha tejida, del año 1964, proveniente de la localidad de Charazani, Bolivia.

Mi trabajo, hasta ese momento, giraba en torno a la historia de los textiles producidos en espacios fabriles de la época moderna de mi país, donde tejedores y operarios cambiaron el curso de la historia política y social, movilizados por la idea de proyectar un país más justo. Esto tenía relación con mi propia historia familiar y mi interés por esos espacios de trabajo textil, dentro de las grandes industrias. El proyecto La Fábrica, que fijaba ese tiempo y su memoria, así como los espacios de trabajo y su obsolescencia, fue abordando distintas etapas y lo constituyeron varias piezas y tejidos.

A medida que avanzaba en la investigación, cada vez más, yo reparaba en pequeñas historias, las más ínfimas, esas que pasan desapercibidas en la historia oficial. Estaba en la búsqueda de esas que consideraba resistencias minúsculas, pero que tenían la cualidad de contener una traza de vedad y que al articularse con otras, van generando los grandes acontecimientos.

De alguna manera esta observación atesoraba una relación con la condición estructural de un textil, donde delgados hilos entrecruzados con otros, van conformando una superficie dúctil y firme, pero que si se aíslan y se ven por separados no revelan su potencial.

En mi encuentro con la huincha de Charazani, esa perspectiva nuevamente me hacía eco. En ella observaba como un pequeño fragmento de tejido, que no superaba los 40 cm. de largo, y los 6,5 de ancho, podía contener el recorrido hecho por hombres y mujeres y ser el resultado de exquisitas tecnologías textiles, fusión de cultura andina Aymara y Quechua, que albergaba de manera única su memoria y noción de mundo.

Abriendo el diálogo y el trabajo con esta pieza, recuerdo las palabras de una gran tejedora Quechua, ella decía que las superficies engañan y hablaba de como el objeto textil tiene una condición de estar vivo, al estar construido a partir de la materia que proviene de la tierra (algodón, lana de alpaca o llama) y la acción de la tejedora, instando a tratar de entender las articulaciones entre las diferentes partes de su estructura, invitando a reparar justamente en aquello que es invisible a la vista y que habita dentro de la organización material de un textil.

Considerando y aprendiendo de esta pequeña pieza textil, comencé el estudio contextual de la pieza, lo hice de la manera más humilde posible, desglosando sus elementos, variaciones y posibilidades, acercándome a través de esta huincha tejida, a la antigua región cultural Kallawaya, ubicada entre los andes y la selva boliviana. De los kallawaya descienden los encargados de proveer la medicina en el imperio inca, tierras en las que aún se custodian saberes curativos, que abarcan las acciones humanas con el entorno, la herbolaria, alimentación y por cierto la producción textil.

El proyecto Charazani devino entonces en una investigación que me llevo a transitar en un comienzo por las posibilidades de la tecnología textil que estaba contenida en esa pequeña banda tejida, caminé por la herencia andina del tejido, escuchado e insistiendo en sus colores y ritmos, así como en las composiciones de llaves y caballos de Charazani. Bajo la idea del módulo, trabajé insistiendo en la repetición, haciendo desplazamientos hacia la serigrafía y grandes extensiones impresas con la iconografía proyectada por los imaginarios kallawaya.

Escuché en silencio los ritmos de mi telar en este encuentro con las culturas de mi territorio. tejí colores y franjas, teji llaves y caballos, traspasé a tela lo que veía. Me gusta imaginar que tejí un puente entre lo que soy y los grandes tejedores de las tierras en que vivo. Los sonidos de mis urdimbres hicieron eco de esa historia, ayudándome a recordar mi propia herencia, lo que ayuda a entender nuestras minúsculas existencias y el breve lugar que uno ocupa en el mundo.