“People make meaningful objects, but they can also change the meaning of objects”

Howard Morphy

Bold and chunky, delicate and feminine, unabashedly plastic or patriotic, the need to adorn oneself with objects, precious or otherwise is part of an everyday ritual that is experienced by each one of us. Objects, in their tangibility assist us by defining a vocabulary for mapping out meanings within a specific society and providing us with an index for analyzing the graph of cultural change. A precious “object”, be it a piece of jewellery or an ornamented silver drinking vessel, firmly speaks not only about the rich traditions of the land it belongs to, but also provides insight into the social order, customs, beliefs, occupations and recreational pastimes of a particular society. The process of development from craft to designed objects can dictate a meaningful narrative that allows us to understand the factors influencing the identity of a culture and society.

Moreover, the relationship between the object and the self is another consideration in this narrative. As Daniel Miller in one of his most significant texts, Material Culture and Mass Consumption, states that “the phenomena of certain mundane objects became so firmly associated with an individual that they are understood as literal extensions of that individual’s being. In many societies, the clothing, ornaments and tools belonging to an individual may be considered so integral to him or her that to touch or do harm to these inanimate objects is considered indistinguishable from taking the same action against the person. Such property is identical to that person and may stand for that person in his or her absence”.

From our opulent Mughal ancestors to the bejeweled Nizams of Hyderabad, Pakistan lies at the cultural crossroads of a region once coveted for its vast riches and abundant fortunes. Here, jewellery and ornaments have always played an integral part in classifying, categorizing and sizing up the most powerful of men and the most enchantingly beautiful of women. Whether they are the simple glass bangles that adorn the arms of the women of Cholistan, or the bold and brassy payal (anklets) of the dancing girls, it is of no surprise that this chaotic land of vastly contrasting races, faces, opinions and lifestyles is home to many quiet revolutions and whispered controversies.

Fresh out of grad school from Sydney, Australia, the last couple of months had been spent seeking a sense of direction and belonging. A timely visit by renowned artist and academic Professor Salima Hashmi, who curated a show of contemporary Pakistani artists at the Ivan Dougherty Gallery at that time, proved to be karmic! Professor Hashmi was envisioning a new school, a place where contemporary art and design would be taught with “no strings attached” and where contemporary jewellery and objects would find a voice. The stage had already been set. The European Union, keen to invest in Pakistan, had funded a study to analyse the gems and jewellery sector with the aim to create awareness of a changing design aesthetic to cater to the export market. This sowed the seeds for a formal academic programme to impart knowledge and skills in the subject of jewellery design to harness the small, but unruly gang of jewellery manufacturers and retailers in Lahore, the historical and cultural capital heart of Pakistan.

Despite the fact that the jewellery industry has been a “boys” playground until now, with men dominating both the workshops and the retail stores, a small storm started brewing. Jewellery had never been a subject worthy of an academic degree or for that matter, a respectable career. According to popular belief, a jeweller had no scruples and would “sell off his own mother for a profit”. With more professional women on the “rampage” much to the distress of their male counterparts, and the urgent search for a newly defined sense of being, the challenge lay in gratifying a new, brave, bold and adventurous market which was rebelling against the norms, but at the same time, was aesthetically and culturally sensitive. Jewellery from across the border from India had been fulfilling the demands of the traditional marketplace, where cheap replicas of European fine jewellery and costume jewellery from China were unable to address this growing need.

Hence, when not one but two academic institutes in the country started offering an undergraduate degree in jewellery, the skeptics had a field day. The jewellery and objects coming to life from these studios were conceptual in nature, sought unconventional materials, explored new technologies and questioned the meaning and value of both traditional and contemporary jewellery through the process and practice of making. It not only questioned the historical, cultural, aesthetic and emotional significance of jewellery and accessories, but also embraced it within the context of a wider discourse of contemporary sensibilities emerging in art and design globally. The challenge was clearly to find an alternate narrative to the shifting perceptions of body ornamentation. Interestingly enough, the programme attracted and engaged largely female students who hammered, drilled and forged metal to fabricate sensuous sculptural forms, which couldn’t be traced back to the dog-eared Hong Kong catalogues doing the rounds of the workshops in Rang Mahal or Dhobi Mandi, that had long been established as the hub of the jewellery industry in the city.

Ten odd years later, the graduates of these degree programmes, along with many others armed with diplomas, undergraduate and postgraduate degrees from well-known art schools like Central Saint Martins, Cranbrook Academy of Arts and GIA (Gemological Institute of America) are turning the storm into a raging tempest. Trendy jewellery brands like Accessorize and Outhouse jostle for space with Swarovski and Bvlgari. Regional heavyweights like Damas and Amrapali dominate the precious fine jewellery sector, but the emerging winners are the small pop up stores, salons and galleries that are showcasing the slow but steady rise of artist jewelers.

The likes of Misha Habib, Zohra Rahman, Amber Sami, Kiran Aman and Aiza Mahmood to mention a few, are promising an alternate narrative. Either trained as jewellery makers or personally training a team of local craftspeople, this persevering bunch of women (a fact worth mentioning) are making dents in the right places. Their baubles are steadily plotting the path for many more following their lead. Bright and spirited, their vocabulary is full of expletives like glass, paper and plastic.

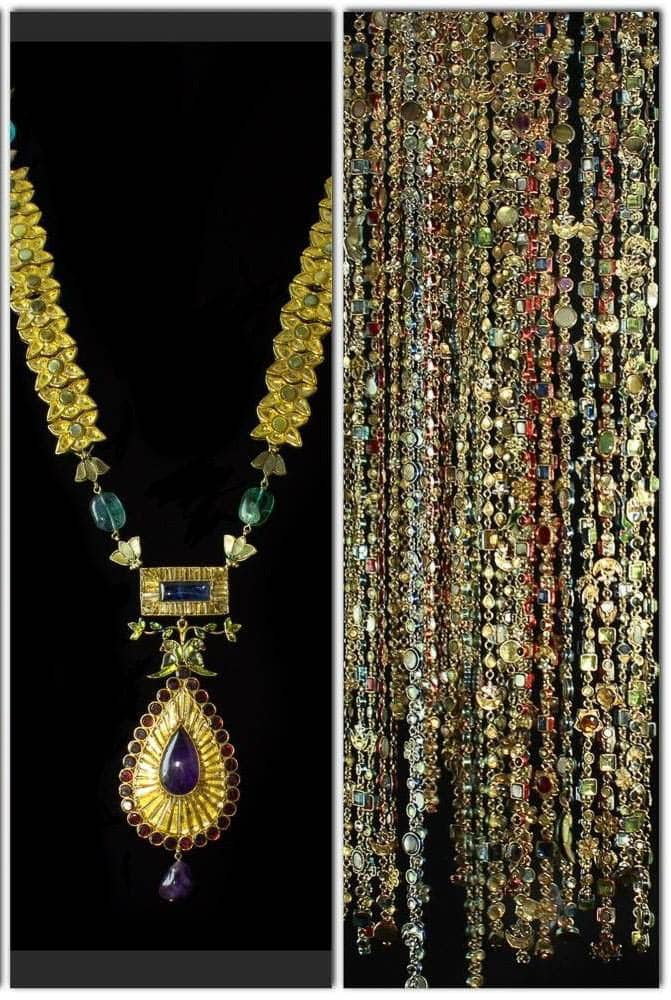

- Amber Sami, Neckpieces from ‘The Persian Garden’ collection

- Amber Sami, Silver charms

Amber Sami, a graduate of Pratt institute left behind the slick life of New York City to discover her passion for jewellery in the streets and bazaars of her home city. Embracing themes from the geometry of the Mughal gardens to the lunar cycles, Sami’s signature collection offers a visual treat. One encounters a vibrant green ‘mian mithu’ parrot curling itself into a patriotic enameled crescent as it transforms into an earring, while another glossy champagne coloured pair is nestled amongst the leafy boughs in the ‘Persian Garden’ collection. Primarily in silver, semi-precious stones and faceted glass, Sami has developed a narrative around a set of potent symbols to reveal the layers of meanings and memories. Patiently guiding her craftsmen to appreciate a re-awakening of the five senses, cultural icons like the ‘guddi’ (kite), ‘panja’ (open palm) and ‘chand baali’ (crescent moon) hang as charms threaded through her neckpieces, reminiscent of the Sufi malang who has, not a care in the world.

- Zohra Rahman, Sterling Silver, 2016

- Zohra Rahman, Neckpiece and earrings from ‘The Gold are Venomous’ collection, photo: Matthew Monfredi

In stark minimalist contrast, stylized tiger claws in sterling silver adorn the huntsman’s neck in Zohra Rahman’s bold Mohenjodaro collection, her debut collection after her return home. Starting off with a few commissioned works in an effort to just get back to work after spending four years in London pursuing her undergraduate degree at Central Saint Martins, Rahman gradually set up her studio workshop and hired an apprentice who would be her “partner in crime”. Determined to start her own collection, she turned towards the Indus Valley civilization for inspiration, the seat of culture in this region. Exploring forms that firmly echoed the cultural corridors of the city and sent one packing home, it represents four personalities re-imagined by Rahman, as integral to this civilisation, namely the huntsman, the builder, the charmer and the vandal. Rahman’s most recent collection celebrates the mystical snake charmer. Entangled and sinful, the sinuous gold and silver forms wrap around the neck, wrists and ears. Meticulously crafted employing the technique of overlapping metal discs in traditional armour, the collection promises to be “venomous”.

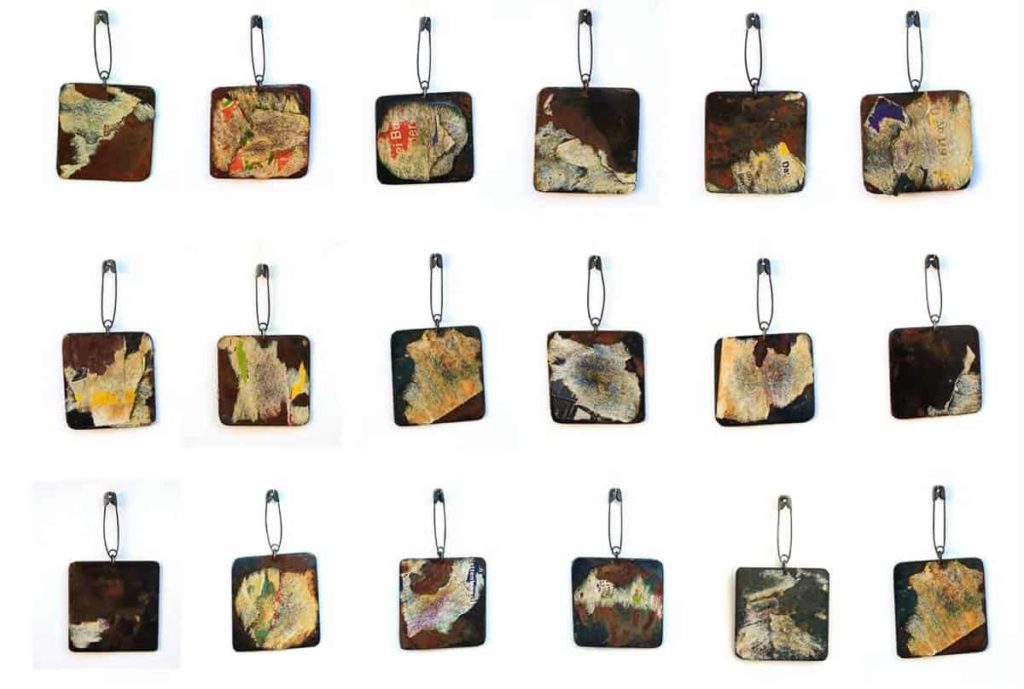

- Aiza Mahmood, “Set us free” pins, 2015, iron and paper , 2.5 x 1.5 inch (approx)

- Aiza Mahmood, Necklace 3, 2015, iron, river stone, 40.6cm X 13.4cm

- Aiza Mahmood, Necklace 4, 2015, iron, river stone, granite, 45.7cm X 16.5cm

Contemporary jewellery forms jostling for space and challenging their traditional counterparts was an evident turn observed by Aiza Mahmood, a recent graduate of Trier Hoschule Institute in Idar Oberstein, Germany, on her return home after an overwhelming experience of self- discovery. After an undergraduate degree in jewellery & Accessory Design from the Beaconhouse National University, Mahmood taught several courses in Computer Aided Design and Product Design before deciding that she wanted to pursue a career as a jewellery maker. Her Set us free pins, a series in response to the Syrian Refugee Crisis, which provoked mixed feelings and sentiments in Europe, was the beginning of a journey that would position Mahmood to scratch below the surface for answers to the many questions she had been pondering over after her departure from the city she grew up in.

The wealth of raw gemstones and minerals in the mining town of Idar Oberstein, Germany has undoubtedly fueled a love affair, which is now bursting at the seams. After a struggle with the local custom authorities to convince them that her jewellery was nothing but invaluable pieces of iron in an effort to transport her work back home, she is slowly warming up to the inspirations the city has to offer her once again, albeit through a changed perspective.

It is, therefore, not a surprising fact perhaps that the city that is home to a host of myriad cultural adventures, like the Lahore Literary Festival (LLF), the Faiz Mela, the Lahore International Children’s Film Festival and numerous others indulges its occupants to keep asking for more. Platforms like the Pakistan Fashion Design Council (PFDC) which showcase established and upcoming fashion designers have witnessed a burgeoning trend of bespoke jewellery and accessories adorning the catwalk by seasoned designers like Fahad Hussayn, Ali Xeeshan and Khaddi at their glamorous fashion weeks, which nudge the trendsetters and send the “bold and the beautiful” into a tizzy.

Though it will take time for the full impact of the contemporary jewellery trend to be felt, it is safe to say that it is looking for an even firmer place in the visual, social and aesthetic legacies of the land. How it evolves to enter a new realm of possibilities is something that needs to be keenly observed and documented. Needless to say, it has sparked a conversation which was previously restricted only to the traditional forms being churned out by the local craftsmen in the industry and will open up new areas of investigations that hold the promise of new alliances with the rapidly maturing field of contemporary arts in Pakistan.

Author

Sahr Bashir graduated in 2001 with a Postgraduate Degree in Design from the College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. Currently Associate Professor and Head of the Jewelry & Accessory Department at the School of Visual Art & Design, Beaconhouse National University, Sahr took the lead in establishing the department, the first of its kind in Pakistan. With over fifteen years of experience in the Education sector, she has played a pivotal role in developing curricula and educational materials in addition to training faculty, professionals, craftspeople and students. Sahr has taken special initiatives to introduce product development and training modules for community engagement in liaison with established government and private organizations in Pakistan. This has led to the implementation of several design interventions for craftspeople and women especially from the underdeveloped communities of Punjab.

Sahr Bashir graduated in 2001 with a Postgraduate Degree in Design from the College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. Currently Associate Professor and Head of the Jewelry & Accessory Department at the School of Visual Art & Design, Beaconhouse National University, Sahr took the lead in establishing the department, the first of its kind in Pakistan. With over fifteen years of experience in the Education sector, she has played a pivotal role in developing curricula and educational materials in addition to training faculty, professionals, craftspeople and students. Sahr has taken special initiatives to introduce product development and training modules for community engagement in liaison with established government and private organizations in Pakistan. This has led to the implementation of several design interventions for craftspeople and women especially from the underdeveloped communities of Punjab.

Comments

Excellent write-up!