Reflecting on his experience commissioning kāvads, Ishan Khosla writes about what a global pandemic can teach us about new ways of working with craftspeople.

(A message to the reader in Hindi.)

(A message to the reader in English.)

This body of work was created from a commission from the Indian Ocean Craft Triennial (IOTA) being held in Perth, Western Australia, between September and November 2021. The John Curtin Gallery and Fremantle Arts Centre are the central exhibiting venues of the Triennial. A further twenty or so venues are planning and curating their own exhibitions in support of the Triennial. Artists included in the show span the Indian Ocean regions and, apart from Australia, belong to India, Indonesia, Kenya, Malaysia, Singapore, South Africa and Thailand.

While the artwork was commissioned before the start of the pandemic, most of the work happened during the pandemic, which greatly impacted various decisions, working methodologies and outcomes as a result. While many craftspeople have suffered due to the pandemic from a lack of in-person customers and orders, I believe that this experience of working remotely with the aid of smartphones and software such as Whatsapp, Google Translate and others, can open up new pathways not just for craftspeople but also for designers from around the world to engage with craftspeople. This is especially the case as even a couple of years ago most craftspeople didn’t have smartphones.

The artwork

The artwork was made in collaboration with Anoop Sharma, Akhlaq Ahmad, Bhajju Shyam, Kiritbhai Jayantibhai Chittara, Pradyumna Kumar and Pushpa Kumari, Tasleem Ahmad and Vijay Joshi. It is an attempt to reconcile the reverence for all living creatures, in animistic traditions and religions such as Hinduism—where the vehicles of gods (vāhānă) and even some gods take the form of animals, with the mass decimation of animals by humans around the world. It addresses one of the key curatorial themes of the exhibition—the “sacred in the everyday” demonstrated through objects and actions around ritual and ceremony.

The title of the artwork, văn se vănvās (exile from the forest), poignantly reminds us of the Sanskrit word for exile, vănvās, that prominently features in the great Hindu epic, The Rāmayan, where Lord Rām, his wife, Sita and his brother, Laxman, are forced to retreat to the forest. Today, with hardly any forest cover, ironically it is animals that are being forced out of their habitats by humans. Indeed only 4% of all animals are in the wild, the rest are domesticated or bred for human consumption. 1.David Attenborough, Planet Earth, Netflix

The depiction of animals and animistic gods by folk and tribal artists have been going on since time immemorial. The artworks are essentially a dialogue between myself and the folk and tribal artists that question the consequence of the commodification and extinction of animals 2.Over 900 species of animals have become extinct according to latest IUCN Red List, 05 September 2021: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/wildlife-biodiversity/over-900-species-of-animals-have-become-extinct-according-to-latest-iucn-red-list-78836, especially the ones associated with a god or their vehicle. The use of branding and packaging has been done to emphasise the capitalistic forces at work that have transformed our relationship with animals from one of fear, awe and respect to that of objects and resources to be mined for consumption and profiteering. Tropes such as humour, parody, and exaggeration are employed as critical graphic devices to draw attention to the mistreatment of animals.

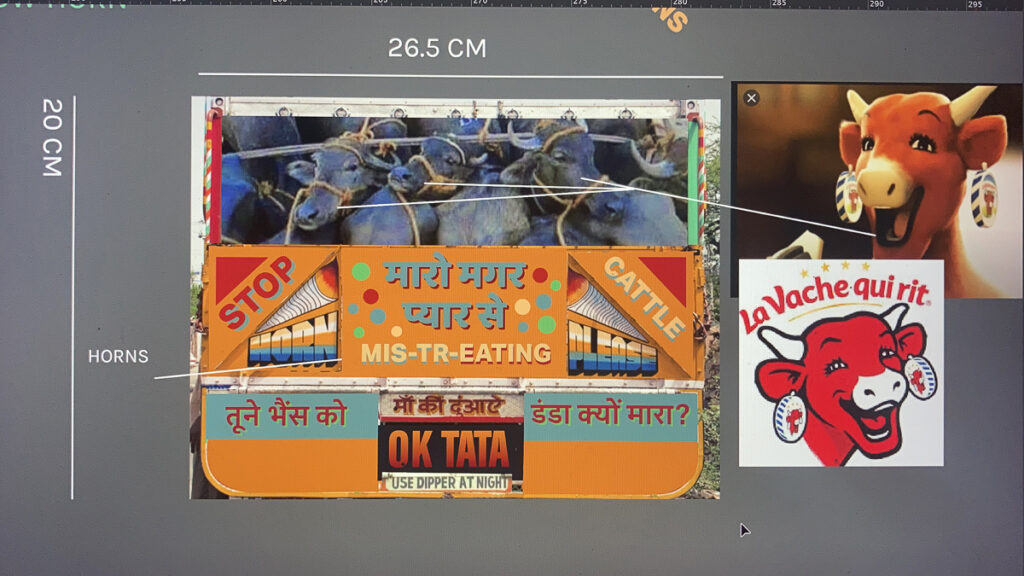

- Reference images for the artist, Anoop Sharma

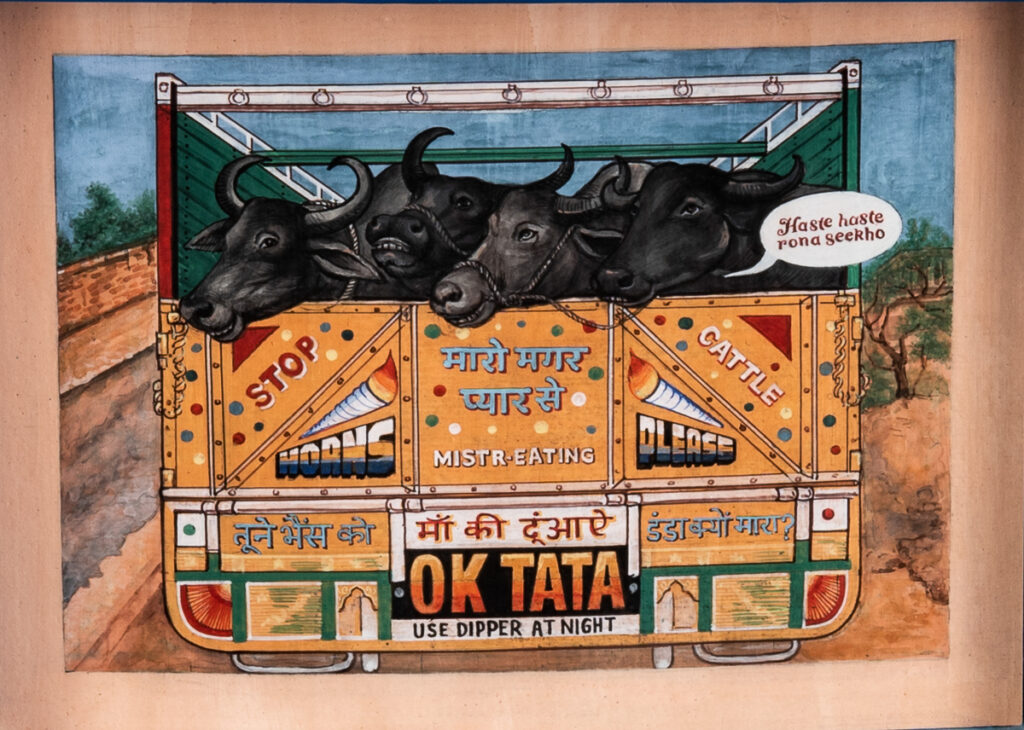

- Completed artwork in collaboration with Anoop Sharma

The statements made in the artworks reference literary and popular culture such as muhawaras (proverbs) as well as songs, dialogues and film titles taken from Hindi cinema. Some of the graphics are a homage to nineteenth-century artists like Raja Ravi Varma who used Hindu iconography for creating “calendar art” and on branding labels for various products. The title of the artwork, Tu cheese badi hai măst măst (You are a delightful thing) refers to a Hindi song of the same name and is used here to highlight the double entendre and the objectification of cows using the word “cheese” — as in the product made from milk and “thing” in Hindi. The panel where the text of this song appears is inspired by the Pichwai paintings of Nathdwara that depict “dancing cows” that move freely across the landscape and juxtaposes that with the depiction of cows confined in a factory.

Cover of the artwork, Tu cheese badi hai măst măst (You are a delightful thing) reminiscent of commercial milk packaging. The exaggerated use of ‘over-selling’ the product is intentional along with various subliminal messages

While the cover of the artwork emphasises the commodification and “branding” of animals by referring to contemporary milk packaging, the central panel depicts buffaloes being forcefully carried on a truck to be slaughtered—a scene so common in India, which is one of the largest exporters of beef in the world 3.Beef2Live—that this image has become a part of the vernacular pastiche.

- A digital mock-up and the final artwork depicting buffaloes being taken to be slaughtered. This image is filled with cultural references and puns. The ubiquitous “Horn Please” seen on the back of trucks everywhere in the country becomes “Horns Please”. While the painted “Stop” sign becomes a call for action to prevent the mistreatment of cattle. The Hindi phrase painted on trucks to ward off the evil eye, “dekho magar pyaar se” (look at me, albeit with love) is twisted to “maro magar pyaar se” (kill me, albeit with love).

- A digital mock-up and the final artwork depicting buffaloes being taken to be slaughtered. This image is filled with cultural references and puns. The ubiquitous “Horn Please” seen on the back of trucks everywhere in the country becomes “Horns Please”. While the painted “Stop” sign becomes a call for action to prevent the mistreatment of cattle. The Hindi phrase painted on trucks to ward off the evil eye, “dekho magar pyaar se” (look at me, albeit with love) is twisted to “maro magar pyaar se” (kill me, albeit with love).

The text “Haste haste rona seekho” (learn to cry by laughing) not only refers to a Bollywood song with the same name but also to many cheese brands that depict happy and laughing cows on their packaging. In reality, the cows suffer from over-milking and mastitis caused by BsT (Bovine somatotropin or Bovine Growth Hormone) injections produced by companies such as Monsanto 4.Essen Rivesta, p5, S. Radika, E. Ramba).

Cover of the artwork, Aapki vikās meri văn se vănvās (Your progress is my exile from the forest) featuring lettering by Akhlaq Ahmed in the style of Bollywood Sign Painting and Truck Art

The use of film dialogues and Bollywood Sign Painting in artworks like Aapki vikās meri văn se vănvās (Your progress is my exile from the forest) are especially pertinent to a medium that itself predates cinema as a narrative device – not just to be seen but to be heard as well. In relation to that, I have included films that I made from this documentation of cows, elephants and other animals to be placed inside some of the artworks as a looped video. Previously, the kāvads would be recited by the kāvadiyā bhāts, who seem to have all but disappeared in the dust of forgotten times. This artwork instead consists of the liberal use of text, whether hand-painted or created on the computer, in Hindi, English or even Hinglish, as its voice. Spoken in the first person, most dialogues are from the perspective of the animal being depicted in a particular artwork.

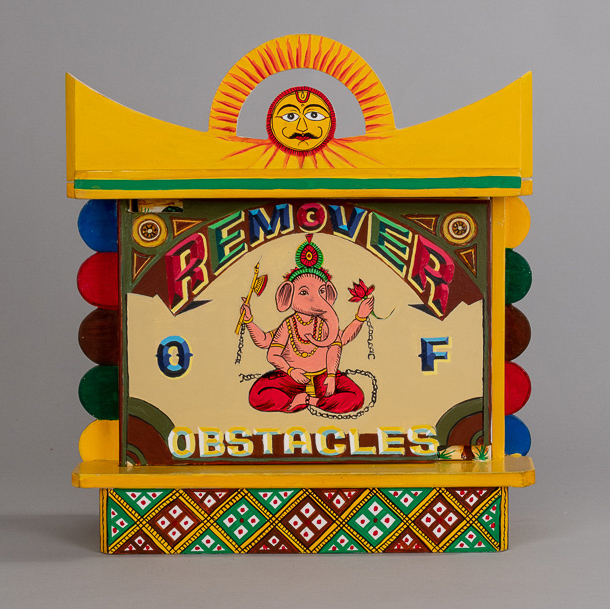

Ultimately, the medium of the kāvad (a portable wooden shrine that also works as a narrative device) seems appropriate for this work, as the artwork uses, references or is inspired by various Indian graphical forms and narrative traditions.

The voice of a craft

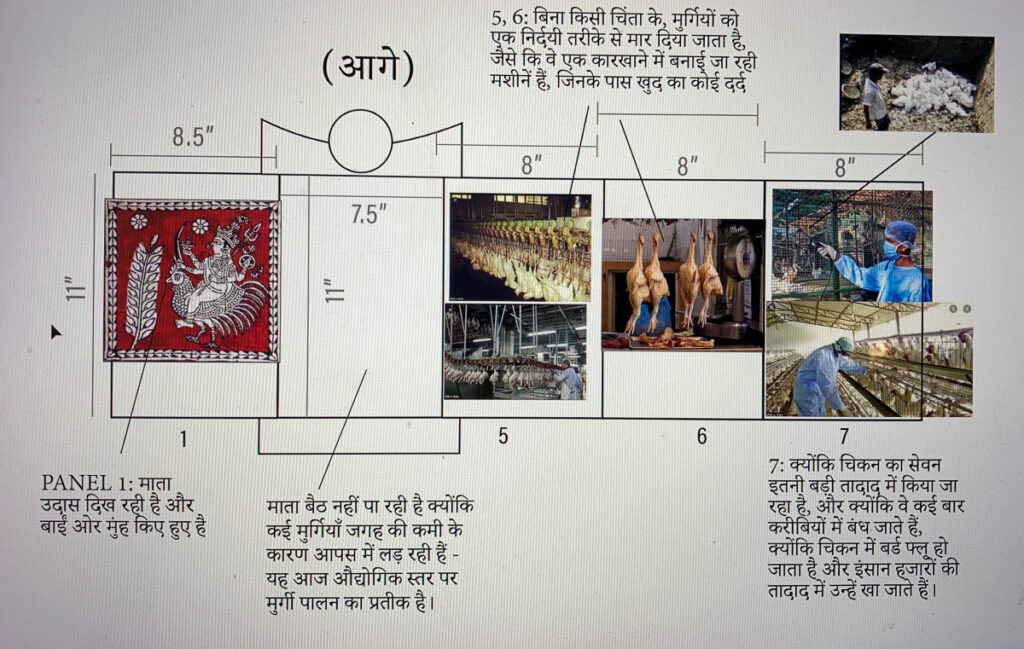

The cover of the artwork, Ghar ki murgi dal barabar, inspired by commercial packaging, McDonald’s storefronts and slogans promoting broiler and eggs such as ‘free range’. The bracketing on either side is a reference to the feathers of a rooster

Even though the form of the artworks are inspired by the kāvad, they are not made by the suthars (carpenters) from the village of Bassi in the Chittorgarh district of Rajasthan from where the kāvad originates. Instead, they have been made by Tasleem Ahmed who is not just a carpenter but in a sense also a designer based in Delhi. He came up with innovative ideas and improvements to the existing kāvad structure. To prevent doors from sliding backwards, he devised a bracketing on either side of the main kāvad structure that not only held the panels in place, but that could also be customised to relate to some aspect of the animal being depicted. For instance, the teeth of the tiger, the udder of a cow and the feathers of a rooster are not just a bracketing device holding the panels in place but are also aesthetic devices that connect the kāvad to the respective animal being represented. Since various structural innovations and surface artwork were done by craftspeople belonging to various “non-kāvad” based traditions, these works should not be considered as kāvads.

You might wonder why I didn’t work with the “original” makers of the kāvad. The challenges of COVID, and not being able to travel to Bassi spurred this decision as was my previous vexing experience with several suthars. They were loath to try out new designs, to use new and more durable materials, and could never deliver the work on time. The proximity, efficiency and professionalism of urban carpenters and their openness to try new ideas made the decision to work with them obvious.

Of course, this is not the first or the last time this has been done. The kāvad has been used outside its location of origin by renowned artists such as Gulammohammad Sheikh, whose exhibition at the Lalit Kala Akademi in Delhi a few years ago made a deep impact on my mind. He used the “language” of the kāvad but played with scale and structure as a means to alter the narrative and the impact of the work.

- The computer mockup of the artwork Ghar ki murgi dal barabar, used to explain the concept to the artist, Kiritbhai Jayantibhai Chittara

- The completed artwork by Kiritbhai Jayantibhai Chittara in the mata-ni-pachedi style of hand painted (kalamkari) and hand dyed cloth from Ahmedabad, Gujarat

Not only are the formats and sizes of these artworks different from traditional kāvads, but we experimented with the way in which the panels would unravel based on the story being told. This meant that not all kāvads were symmetric or identical in structure. For instance, Ghar ki murgi dal barabar (A homemade chicken is as humdrum as a serving of lentils) which looks at the overproduction of poultry, has just one panel on the left and three on the right to support the narrative of the goddess Bahuchāra who sits on a rooster, looking away from all the injustices that are taking place on the right three panels.

Animation showing the opening of Băndar kyā jaane adrăk kā swād (How should a monkey know the taste of ginger) — emphasizing the way Hanuman opens his chest to reveal his devotion to Lord Ram and Sita.

The artwork on the exploitations of monkeys, called Băndar kyā jaane adrăk kā swād (How should a monkey know the taste of ginger) was designed to open in a way to evoke the iconic image of Hanumān opening his chest to reveal Lord Rām and Sitā, except here he’s opening himself to reveal the story of the kingdom of monkeys being subjected to all sorts of cruelty by the very people that worship him.

Craft collaborations during the global pandemic

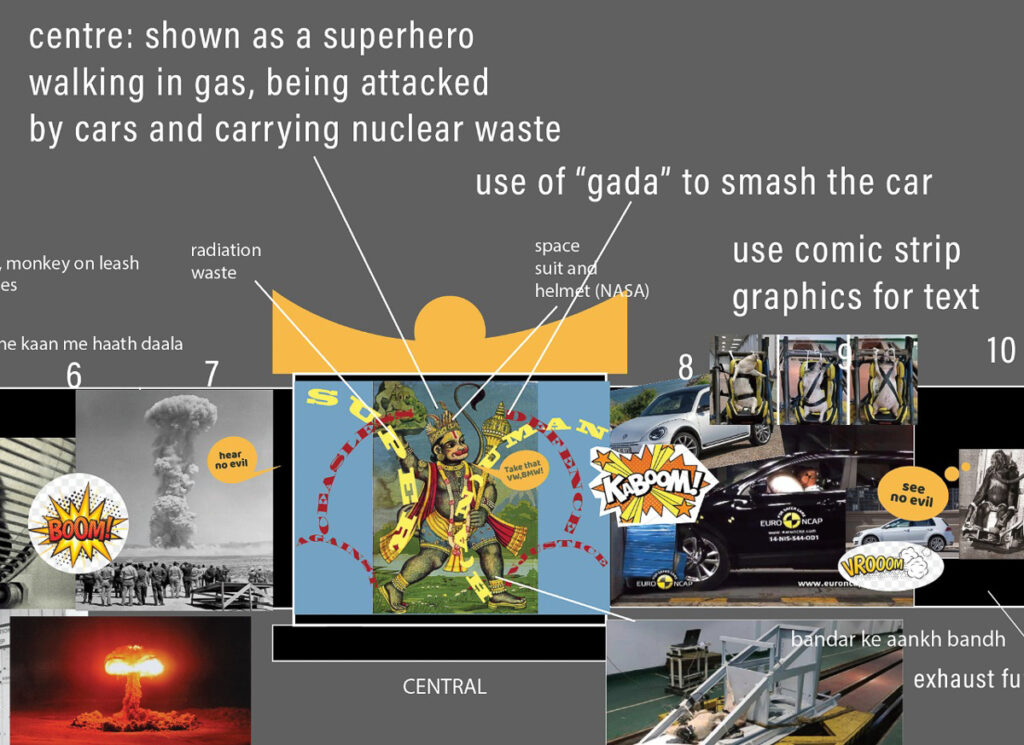

- Mockups made on Adobe Illustrator using found images, and created vectors to indicate the elements to be used in the artwork on the various panels of Băndar kyā jaane adrăk kā swād

- Mockups made on Adobe Illustrator using found images, and created vectors to indicate the elements to be used in the artwork on the various panels of Băndar kyā jaane adrăk kā swād

- Completed artworks by Anoop Sharma of the corresponding panels

The nine artworks were made in collaboration with some of the most renowned contemporary folk and tribal artists in the country. Most of them continue to work in their respective artistic traditions while addressing subjects that are pertinent today. While I have collaborated with most of the artists before, working virtually on physical, handmade objects, that not only needed to tell a story in a certain sequence but were loaded with layers of symbolism, metaphors and puns, was arduous. The kāvad sent to Bhajju Shyam was dismantled by the carpenter, which meant figuring out the correct sequence of panels for Bhajju to paint on. It became so complex to explain via a video phone call, that I had to use a combination of WhatsApp videos and annotations to explain this to him. Works by Kiritbhai Jayantibhai Chittara were to be made on cloth as is done in the craft of mata-ni-pachedi. In which case it was decided to measure each panel and send it to him, which in itself became confusing for him to remember which panel number corresponded to which artwork (see video and video). Similarly, various types of image references and digital mockups had to be created for Anoop Sharma to articulate the various visual references to be used in the artwork, Băndar kyā jaane adrăk kā swād.

The challenge of working during the global pandemic meant that, except for a couple of initial meetings, I never met any of the artists face to face during the making of the artworks, which has never happened before in all my previous engagements with craftspeople. This way of working was only possible due to the ubiquity of smartphones and especially due to digital tools such WhatsApp which allows one to share compressed videos, create annotations on images and send voice messages.

- Feedback given to Pushpa and Pradyumna based on their initial sketches after our verbal discussion of the artwork. Also indicated are suggestions on how to proceed with the sketch on the extreme left and extreme right — both of which can use two panels instead of one

- Feedback given to Pushpa and Pradyumna based on their initial sketches after our verbal discussion of the artwork. Also indicated are suggestions on how to proceed with the sketch on the extreme left and extreme right — both of which can use two panels instead of one

Ideas that germinated on paper moved into complex Adobe Illustrator files filled with numerous reference images and mock-ups of each of the kāvads. These were created to explain the background, context and narrative of each work as well as to give feedback to the artists on how to move forward with the sketches already done.

There would usually be a “delay”—sometimes of a few days and at other times of a few weeks—between receiving the sketch from an artist and being able to provide feedback to them and vice-versa. This was due to various factors such as bad network connectivity, conflicts in schedules or even illness. For instance, Kiritbhai and his entire family got COVID, and I didn’t hear from him for weeks.

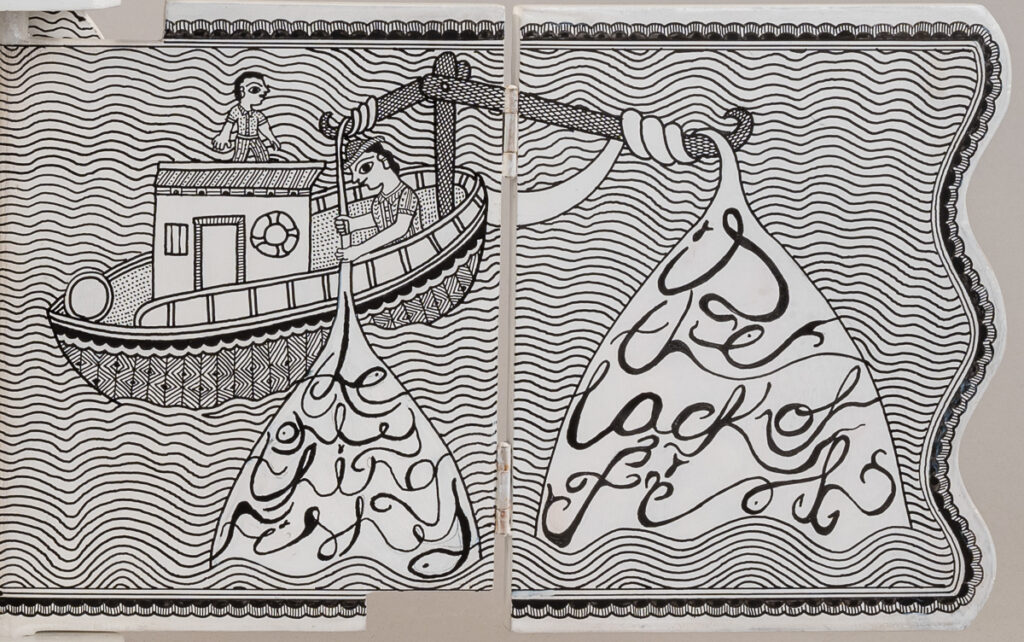

- The empty fishing nets of the artwork, The only thing fishy is the lack of fish: who will save you from the impending flood?, made in collaboration with Pradyumna Kumar and Pushpa Kumari

- The completed lettering of the title

Ironically, working under the constraints of the pandemic was more egalitarian and collaborative as both the artists and I had time to think things through and suggest ways in which to move forward.

This remote and virtual method of working made us work more slowly than we would have done in a face-to-face meeting. This allowed both the craftspeople and myself to take some time to revert back to each other after having thought about the work a bit more. Previously in face-to-face interactions, decisions would have to be made faster as one would have limited time to be face-to-face with the craftsperson at their studio, who would usually be in another city. Ironically, working under the constraints of the pandemic was more egalitarian and collaborative as both the artists and I had time to think things through and suggest ways in which to move forward. Even when things got lost in translation every now and then, the availability of time meant one could mull over and resolve things in this complex artwork—perhaps the most ambitious project I have undertaken to date—in elegant and meaningful ways. For instance, Pushpa and Pradyuman forgot to add the plethora of fish inside the fishing nets in the artwork, The only thing fishy is the lack of fish: who will save you from the impending flood? The empty fishing nets not only felt appropriate but poignant too. Eventually, I decided to add the title using hand lettering inside the fishing nets. The completed work is depicted in the gif animation.

The kāvads had to be sent to craftspeople in various locations around India despite the lockdown which proved to be extremely challenging. Some of the kāvads such as the one sent to a Pattachitra artist in Midnapore, West Bengal never made it in one piece and had to be scrapped. Others had to be sent via a bus or car driver as courier services weren’t always working. Special wooden boxes were also made in some cases to ensure the works would make the journey back and forth in these uncertain times.

Conclusion

The process of creation in this project raises some pertinent questions for the future of craft. Questions such as whether “appropriating” an existing form of one craft by another person (who may or may not be a craftsperson) and who doesn’t belong to that tradition, debase the value of a craft or can it actually help innovate it? Will using technologies to assist in making such as a stylus on a tablet instead of pen on paper be accepted as something hand-crafted? Should craft be allowed to be unbound from these constraints if it is for the greater good?

In previous instances of working with craftspeople, I would typically not necessarily work on the crafted object myself. Can an object created in this fashion that involves the creative output of an urban designer, an urban carpenter, craftspeople and folk artists from various cities, towns and villages be called craft? Why or why not? And who should be deciding this?

With continued COVID restrictions in Western Australia, it is inevitable that more people will engage with these crafted objects through digital technologies via their smartphones or computers, than in person. How will our definitions of craft, the way we engage with it, and the people who make it, change in times to come, especially with a greater dependence on technology?

How do these experiences and interactions with craft change our perception, meaning and value of the handmade? And, what then will be the role of craft going forward?

Further reading

Sacred Animals of India (Nanditha Krishna)

Can the subaltern speak? (Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak)

Big Cat Rescue

International Primate Protection League

TreeHugger.com

World Animal Protection

Greenpeace

PeTA

The Vegan Movement

The Kaavad storytelling tradition of Rajasthan (Nina Sabnani)

The kaavad: from devotion to decoration (Ishan Khosla):

Credits and Thanks

I would like to thank all the artists I collaborated with for this project: Anoop Sharma, Akhlaq Ahmad, Bhajju Shyam, Kiritbhai Jayantibhai Chittara, Pradyumna Kumar and Pushpa Kumari, Tasleem Ahmad and Vijay Joshi. Special thanks to Anoop Sharma and Pradyumna Kumar who persevered through personal illness and loss and continued with the work till the end. Thanks also to the Indian Ocean Crafts Triennial team — Maggie Baxter, Jude Van Der Merwe, Carola Akindale-Obe and Tom Freeman. I am indebted to my wife Shirley Bhatnagar for her support and contribution to the project. All images by Ishan Khosla unless otherwise mentioned.

About Ishan Khosla

I currently live in Dehradoon which is in the foothills of the mighty Himalaya mountains in the frontier state of Uttarakhand. I am an Associate Professor of Design at UPES. I am a visual artist, designer and teacher and also enjoy the lush greenery and natural beauty of this region. One of my favourite things to do is to cycle in the tea gardens near our home. I am currently working on developing letterforms from Indian crafts to be used in contextual primary school education, and also hope to start working on a book in the near future. A project under development is making an edtech app, ‘Shilp-se-shiksha‘ (learning from crafts) based on Indian crafts for learning the alphabet in a contextual manner for primary school children. Follow @thetypecraftinitiative.

I currently live in Dehradoon which is in the foothills of the mighty Himalaya mountains in the frontier state of Uttarakhand. I am an Associate Professor of Design at UPES. I am a visual artist, designer and teacher and also enjoy the lush greenery and natural beauty of this region. One of my favourite things to do is to cycle in the tea gardens near our home. I am currently working on developing letterforms from Indian crafts to be used in contextual primary school education, and also hope to start working on a book in the near future. A project under development is making an edtech app, ‘Shilp-se-shiksha‘ (learning from crafts) based on Indian crafts for learning the alphabet in a contextual manner for primary school children. Follow @thetypecraftinitiative.

Related stories

Stories, theatre and worship: The sacred masks of Majuli

The time-honored Ashavali brocades of Gujarat

Indonesia’s generation Z takes up shibori

Dancing bodies, moving touch: Textiles, materiality and touch in Indian dance

A handmade sky: The people, art and craft behind Kashmir’s Khatamband ceilings

The soul of Feng Huang: An art of contemporary batik pesisir pattern

References

| ↑1 | David Attenborough, Planet Earth, Netflix |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Over 900 species of animals have become extinct according to latest IUCN Red List, 05 September 2021: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/wildlife-biodiversity/over-900-species-of-animals-have-become-extinct-according-to-latest-iucn-red-list-78836 |

| ↑3 | Beef2Live |

| ↑4 | Essen Rivesta, p5, S. Radika, E. Ramba |

Comments

Wow Ishan what an undertaking. I have enjoyed reading this article and visualizing the complexity covid has a added. Your concluding questions thought provoking. Thank you.

Thank you Sandra for your comments. It was indeed a complex project in unprecedented circumstances. I hope people get a real sense of it even though it will be mostly seen virtually.

Very interesting Project and well put together. The visualisation is amazing.