- E Marruffo, Ghostgums, 2012, Acrylic pastel and oil on linen, 130cm x 130cm, photo by E Marruffo

- E Marruffo, The Strawberry Thief She Dares to Dream (detail 2), 2018, silk and alpaca fibres, beads, silk thread on vintage Mexican wedding veil, 280cm x 134cm, photo by E Marruffo

- E Marruffo, The Strawberry Thief She Dares to Dream (detail 1), 2018, silk and alpaca fibres, beads, silk thread on vintage Mexican wedding veil, 280cm x 134cm, photo by E Marruffo

- E Marruffo, The Strawberry Thief She Dares to Dream (detail 3), 2018, silk and alpaca fibres, beads, silk thread on vintage Mexican wedding veil, 280cm x 134cm, photo by E Marruffo

- E Marruffo, Ghostgums (detail), 2012, Acrylic pastel and oil on linen, 130cm x 130cm, photo by E Marruffo

I recall a meticulously painted still-life of a pomegranate. At the time I found it a little twee, it was small and earnestly rendered. No one does that anymore, do they?

I was schooled by the postmodernists at Central TAFE in Perth and had arrived at Edith Cowan University in 2004 with rebellion in my heart, a general distrust of aesthetics, linear narratives and the unironic. Though I studied alongside Elizabeth Marruffo in the painting studios, I could be found doing anything but; perhaps some heartfelt but half-baked installation of found objects and photomedia. While I was busy rejecting conventions, Elizabeth was gaining a deep revere and understanding of the visual languages that make up her cultural fabric, laying down the foundations of an enduring and meaningful art practice. I look back on that painting now and see that depicting the fruit as she did, so unambiguously, was a truly radical act.

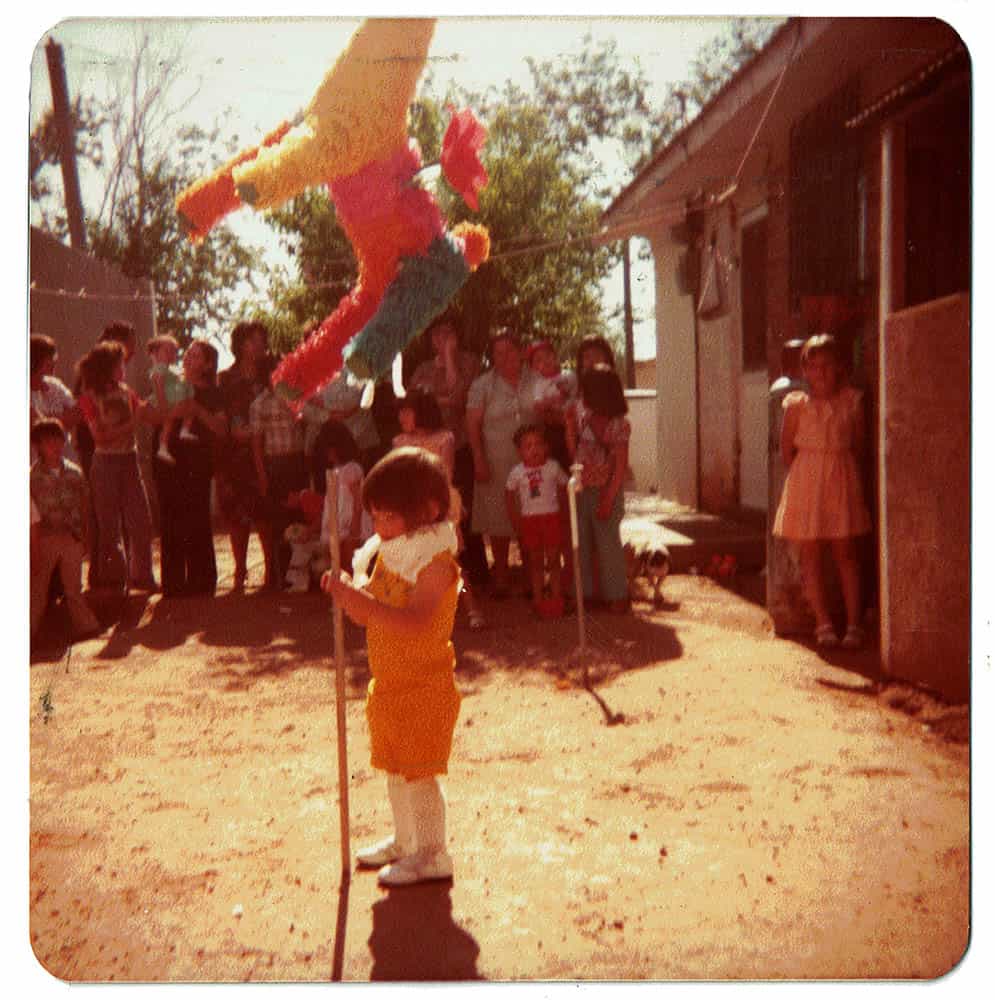

- E Marruffo, Childhood photo, Agua Prieta, 1978

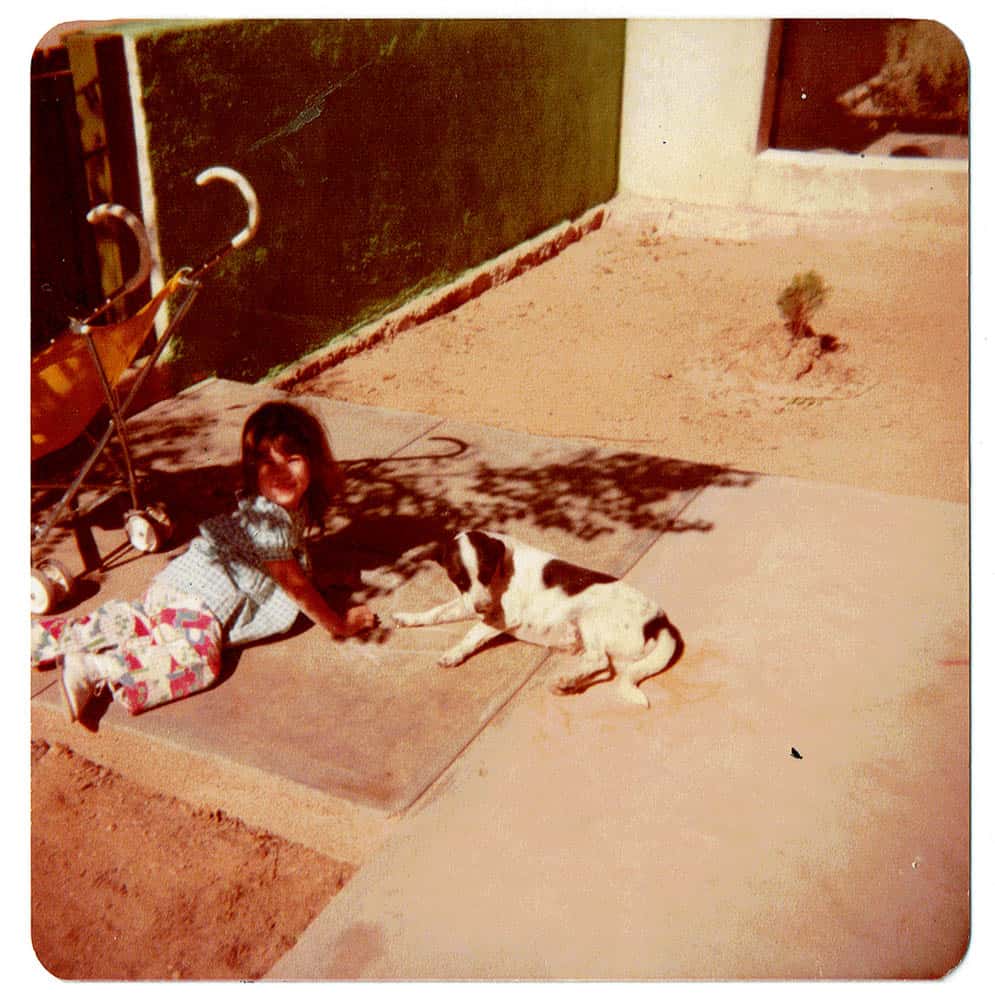

- E Marruffo, childhood photo with her dog Corazon, Agua Prieta, 1978

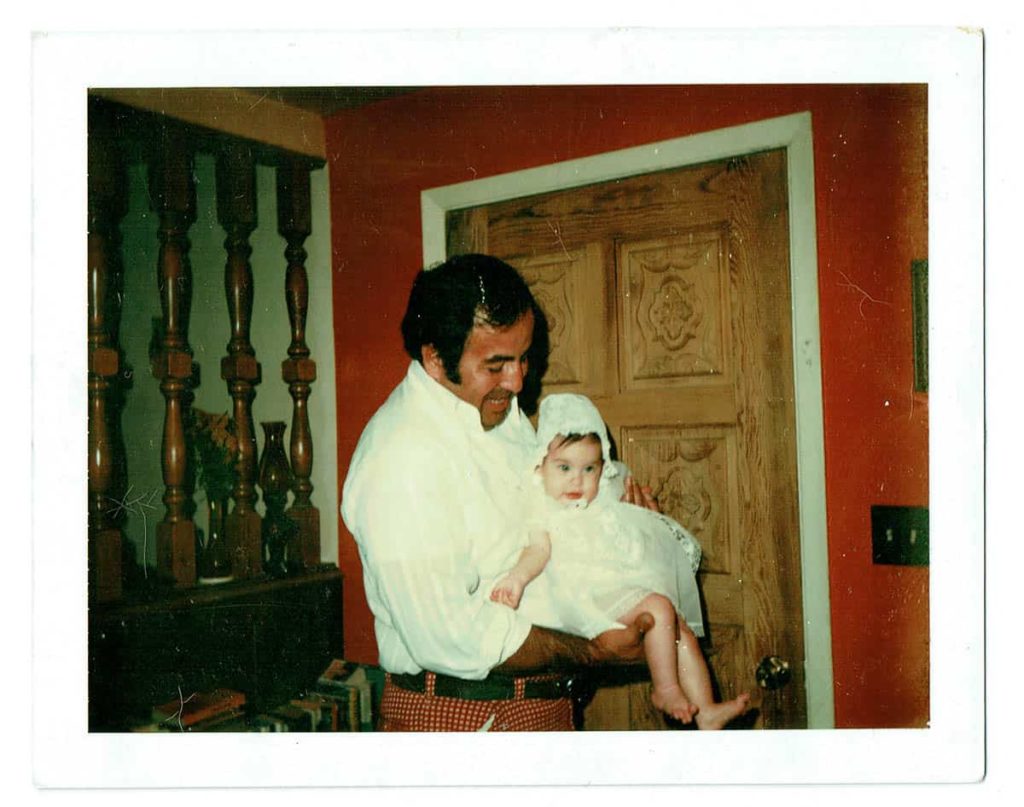

- E Marruffo, childhood photo after being Baptised, Agua Prieta, 1976

Elizabeth spent her early childhood in the arid town of Agua Prieta, before the loss of her Mexican father spurred a move to England—original home to her mother with the itchy foot. How strange that new place must have felt, the rhythms of a different language being spoken, the smells and flavours of a landscape cast under a damp, milky light. Such a stark contrast with that of the Sonoran Desert. The pomegranate—though I imagine a sensory trigger of times past—was a potent expression of her identity, both as a woman and as an English Mexican migrant to Australia. The exotic fruit is so abundant in seeds it is a symbol of fertility, love, lust and is forbidden fruit on the Tree of Life within Mexican folk art. Yes, that pomegranate from art school distilled all of this.

Since the completion of our degrees together, Elizabeth further honed her craft in Italy at the Florence Academy of Art, undertaking intensive workshops in traditional painting. Her well-practised application shows in the fine portrait works that often seemingly float on a far more nebulous background. I was lucky enough to acquire a large canvas by Elizabeth, Ghostgums, 2012, not long after I had returned to Australia from some years living away. Its dreamlike quality, depicting a figure in an impermanent or unknowable landscape, spoke to my mixed feelings of love and unease for this place I call home and yet recognise as not mine at all. While her technique certainly refined during this period so too did the symbolism within the work, with the eerie reappearance of baby animals; a gosling, a rabbit, a puppy and various Mexican cultural artefacts; the piñata, Day of the Dead flags and cactus flowers. This vocabulary of references only grows richer and more complex with each new work, making for an intriguing long game.

Added to her repertoire were also three-dimensional works using the needle felting technique. In 2013 Elizabeth had begun sculpting a series of miniature dogs, considered the wayfinders in the Mexican afterlife; which were suspended above head in a constellation entitled Pup Pup is the Boss of the Stars. Each pup represented the childhood pet of a person who had contributed to the project through a crowdfunding campaign in a bid to get the artist back to Mexico. There were more than 150 of the little darlings, creating a wonderfully sort of lilliputian experience of the night sky and a shared space for love and loss. The Aztec story of the dog Xolotl descending to the underworld is a uniquely Mexican one, but the idea that a person’s first experience of death might be bound to the loss of a canine companion is surely universal.

E Marruffo, The Strawberry Thief She Dares to Dream, 2018, silk and alpaca fibres, beads, silk thread on vintage Mexican wedding veil, 280cm x 134cm, photo by Eva Fernandez

The Tree of Life, an ancient and cross-cultural archetype that seeks to give meaning to existence, reappears in Elizabeth’s recent entry for the Mandorla Art Prize The Strawberry Thief, She Dares to Dream. This time it is the framework for a luminous soft sculpture that takes her Mexican Grandmothers silk wedding veil as its ground. Adorned with delicate needlework, felted birds, glass beaded snakes, baby socks, The Sacred Heart at its apex; the veil holds many hours of handcrafted personal signifiers. As a maker and stitcher of things myself, I see intimacy within this work, the gentle slow hours of working closely with fibres and needle. Each repetition becomes like the passing of a prayer bead, an affirmation to slow down and take care of this thing you are building. An excerpt from her statement for this work reads: “I have used overtly feminine imagery in a sincere attempt to depict great strength and beauty. The delicate appearance of silk belies its inherent strength in the same way that the overtly feminine can sometimes be underestimated.” It is this sincerity in Elizabeth’s work that is unwavering. To express femininity, not from the context of the binary, not as a discussion on gender politics but in a way that seeks to honour and mythologise it.

In recent years my own creative practice has become preoccupied with the crafting of woven vessels. What I have come to understand as radical within Elizabeth’s early work, I discovered through the act of slowing down. Because weaving is so very slow. It is singular, repetitive and humble. As I practice my craft, I am able to live the stories that have come before; finding myth and tradition where I thought I had none.

Artist

Siân Boucherd is an artist, writer and educator based in Perth, Western Australia. With a special interest in basketry and weaving off-loom and her works can currently be found at the JamFactory, Adelaide; FOUND, Fremantle Arts Centre; and Nest Design Studio, Darlington. Sian will be a participating artist in a series of workshops, talks and community activities with a focus on Fibre Art at this year’s York Arts Festival, September 22 & 23.

Siân Boucherd is an artist, writer and educator based in Perth, Western Australia. With a special interest in basketry and weaving off-loom and her works can currently be found at the JamFactory, Adelaide; FOUND, Fremantle Arts Centre; and Nest Design Studio, Darlington. Sian will be a participating artist in a series of workshops, talks and community activities with a focus on Fibre Art at this year’s York Arts Festival, September 22 & 23.