Whale shark at Ningaloo, 2015 photo: flickr member Mattia Valente <https://www.flickr.com/photos/mattia_v/23497139426/>

The charismatic whale shark (Rhincodon typus), the world’s largest living fish, is an ocean wandering filter feeder widely distributed in warm waters. Ningaloo reef off Australia’s west coast is a site of congregation and study of these mysterious majestic creatures listed in 2016 by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as Endangered, at risk of global extinction.

The recently completed Ningaloo Centre in the coastal town of Exmouth, Western Australia provides extensive contemporary interpretation of the nearby Ningaloo Coast World Heritage Area which spans unique adjoining terrestrial and marine ecologies. The building combines a community and visitor centre with exhibition spaces and a working marine research facility. Susan Freeman, a Director of the Sydney-based design agency FRD, was the lead designer of the Centre’s exhibitions.

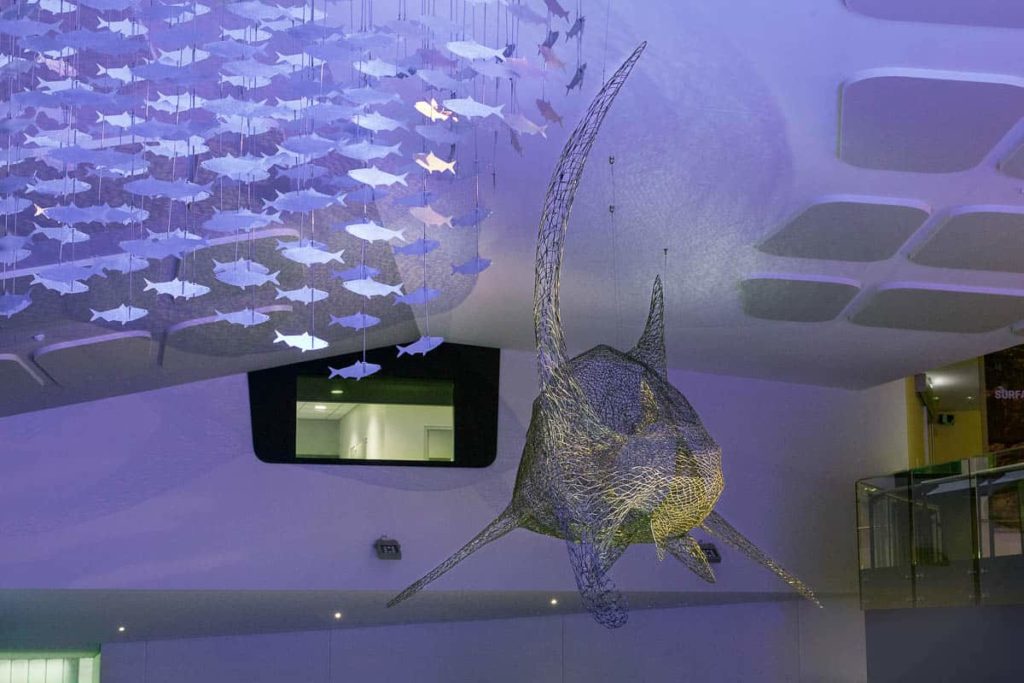

A striking visual feature of the vaulted interior space is a suspended life-size sculptural representation of a whale shark. Not only is the gleaming steel open-framework model at 1:1 scale, it is an accurate biometric recreation of an individual animal. Known to scientists and Facebook friends alike as Stumpy, he has been observed in the wild for over two decades – one of the longest studied animals on Earth.

Susan has an extensive professional career in the cultural sector as an exhibition designer. She is also an ardent ocean swimmer, with an abiding interest in sea creatures such as stingrays, jellyfish, turtles and corals. Research for the Ningaloo Centre project involved various trips to experience the unique values of the World Heritage Area, including swimming with whale sharks. She vividly recounted to me a sublime encounter with the shimmering ocean giant and the elaborate preparations required to make that pelagic meeting.

Ferried out to deep water off the continental shelf on a scientific research vessel, a spotter plane circled overhead to locate a subject whale shark. The boat anchored downstream from the shark’s approach and the wet-suited observers entered the water wearing snorkels, swimming near the surface, peering down into the ocean abyss. As the creature approached, Susan wasn’t quite sure what she was seeing. The massive glimmering body looked like a mesmeric imagining of a distant galaxy. The watery grey-blueness, bright dappling sunlight and the creature’s grey-white dotted skin merged and blurred definition of scale or speed. Though the whale shark seemed to be moving slowly, the observers swam strenuously to maintain visual contact.

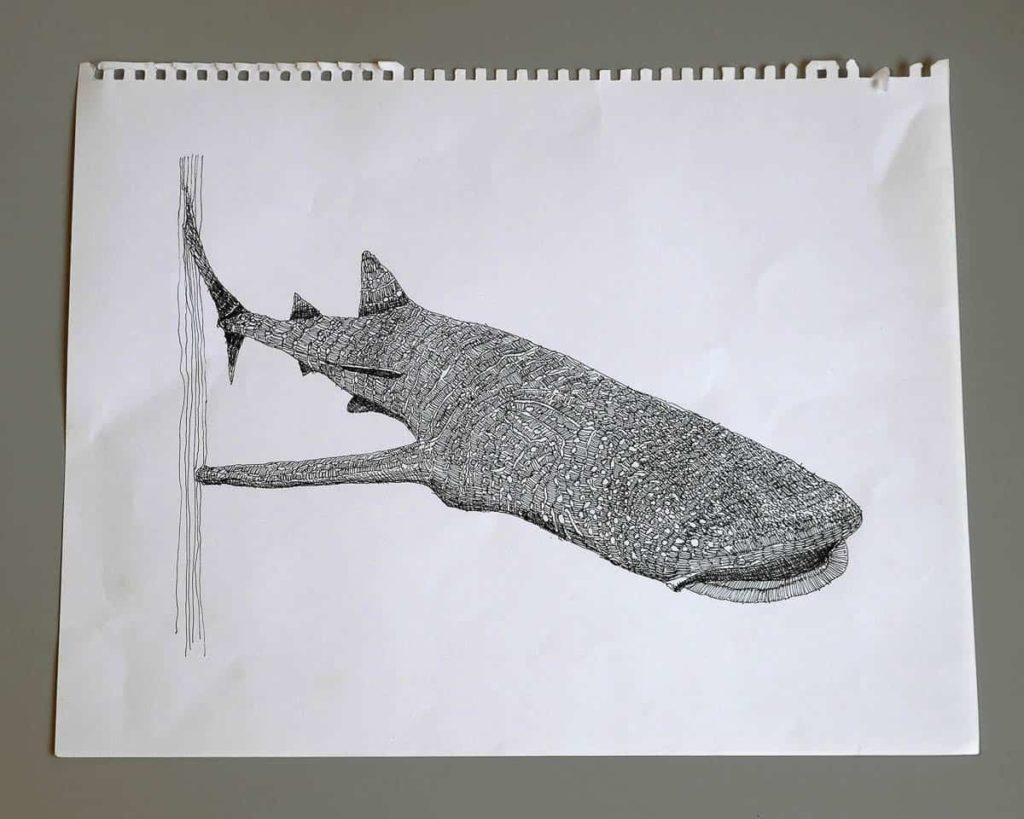

Reflecting on her encounter, Susan decided these poetic qualities of ambiguity, strangeness, spectacular patterning and sensory deception were what she wanted to embody in the sculptural form that would eventually hang in the airspace of the building interior.

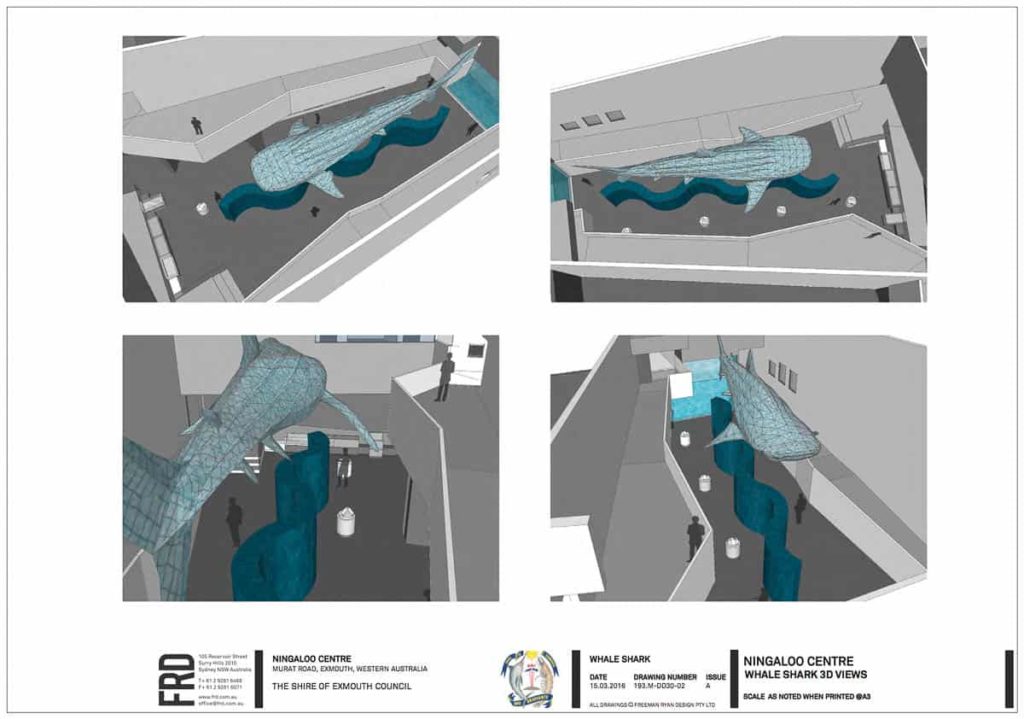

Susan Freeman, Concept sketch for imagined woven whale shark sculpture, 2014, Staedtler ‘pigment liner’ pen photo: Gary Warner

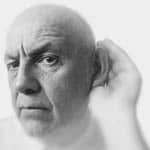

Intent on avoiding the common Australian trope of the roadside ferro-cement or fibreglass Big Thing – be that prawn, merino, lobster or Exmouth’s pre-existing outdoor whale shark near the petrol station – Susan was determined to devise or identify a means to create a distinctive and clearly recognisable form while shifting away from theatrical verisimilitude in favour of poetic abstraction. Initially resistant to this less traditional approach, the Council client was eventually convinced of the concept’s merits through 3-D modelled visualisations and fly-throughs created by FRD.

A Production Brief was written outlining the qualitative and metric requirements of the proposed sculpture, without nominating preferred materials or methodology. The key qualities were that the sculpture must be relatively lightweight, porous to light, abstract yet identifiably a whale shark, and visually interesting at different proximities. Three artists with suitable skills were identified through research and approached to provide a response to the Brief. Fremantle-based sculptor Simon Gilby, who creates large complex forms shaped from welded stainless steel rod, was selected to work with the design team to develop and hand-make the sculpture.

Based on Stumpy’s morphological data provided by leading whale shark expert Brad Norman, Simon’s drawings made after swimming with whale sharks at Exmouth and with the assistance of colleagues from “if lab” at the University of Western Australia, a digital 3-D model was prepared that was used to generate a CNC-cut full-size foam form. Simon then used this form as a substrate to gradually place and weld together thousands of handmade stainless steel rings and individually bent connecting rods. This work took six months, after which Simon was aided by skilled assistants to grind back and polish the welded joints of the elaborate lace-like but robust network. The foam core was removed to reveal the rigid 9m long self-supporting structure which was then cut into manageable sections for road transport 1200km north to Exmouth.

- Simon Gilby, whale shark for Ningaloo Centre – sculpture packed for transport from Fremantle to Exmouth, 2016 photo: Susan Freeman

- Simon Gilby, whale shark for Ningaloo Centre – sculpture packed for transport from Fremantle to Exmouth, 2016 photo: Susan Freeman

The artist and the exhibition installation team laboured over three days in the un-air-conditioned space to reassemble the body, then methodically block-and-tackle lift the form to its engineered ceiling suspension points.

- Simon Gilby, whale shark for Ningaloo Centre – installation in the gallery space, 2016 photo: Susan Freeman

- Ground floor installation view, Ningaloo Centre, Exmouth WA, 2017 photo: John Gollings

Melbourne-based lighting consultant Ben Cisterne devised, installed and programmed a slowly changing lighting array to cast impressive dynamic shadow effects across ceiling and walls, adding to a sense of underwater immersion, movement and change.

- Upper level installation view – bait ball sculpture top left, Ningaloo Centre, Exmouth WA, 2017 photo: John Golling

- Upper level installation view – detail, bait ball sculpture left, whale shark sculpture, right, Ningaloo Centre, Exmouth WA, 2017 photo: John Gollings

Suspended from the ceiling nearby is a large sculptural evocation of schooling fish colloquially known as a “bait ball”. Hand-assembled from 323 laser cut aluminium units arranged in three concentric elliptical rings, this companion sculpture glints under a separate lighting program to contribute additional complex light-play and shadow forms.

Upper level installation view – whale shark interpretation panels top center, Ningaloo Centre, Exmouth WA, 2017 photo: John Gollings

The building’s architect, Paul Edwards of Site Architecture Studio, designed the interior circulation path as a traversable metaphor, a “Reef to Range” journey. The visitors experience of the whale shark sculpture begins on the ground floor entry level, underneath the figure, looking up as if from ocean depths. Walking along the perimeter’s gradually rising encircling ramp to reach the upper gallery, the perspective changes from being underneath to being side-by-side, eye-to-eye. At this point, visitors discover the story of Stumpy and his gallery-bound avatar, and can learn something of the lifecycle of whale sharks (what is known – they’ve never been observed mating or giving birth and precious little is known about their early stages of life).

While many countries now protect whale sharks in their national waters, and by-catch fatalities have been reduced through better fishing practices, hundreds continue to be slaughtered every year by countries including China and Oman—often for shark fin soup, where only the fins are used and the carcass dumped back into the sea. Over the past 50 years, the global population has been drastically reduced, thus the recent Endangered classification.

Susan Freeman and Simon Gilby’s remarkable evocation of this extraordinary marine creature, conjured from the ocean and hand-made from steel, captures and communicates instinctive feelings of natural grace, majestic mystery and cryptic animal otherness. It is not solid in stasis, but elusively permeable, open, subtle, sinuous, and active with purpose to awaken wonder and empathy for this gentle fellow creature threatened through human agency with eternal eviction from its ancient evolutionary home in aquatic time and space.

The author

Gary Warner is an artist and art worker with a studio in Darlinghurst, Sydney and an off-grid bush retreat 50km north-west of there. In 1997 he started CDP Media, a cultural production company that has developed and delivered a wide variety of museum exhibition projects in collaboration with FRD and other designers, architects, artists and curators. His personal art practice spans various media including sound, video, drawing, installation and performance in contexts including writing, curating, collaboration, design, workshops and exhibitions. In 2016 he curated FIELDWORK: artist encounters at the Sydney College of the Arts and was commissioned by FRD to create a permanent multi-screen video installation for a new ceramics gallery at the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. For more information, see garywarner.net, fieldwork.show and cdpmedia.com.au

Gary Warner is an artist and art worker with a studio in Darlinghurst, Sydney and an off-grid bush retreat 50km north-west of there. In 1997 he started CDP Media, a cultural production company that has developed and delivered a wide variety of museum exhibition projects in collaboration with FRD and other designers, architects, artists and curators. His personal art practice spans various media including sound, video, drawing, installation and performance in contexts including writing, curating, collaboration, design, workshops and exhibitions. In 2016 he curated FIELDWORK: artist encounters at the Sydney College of the Arts and was commissioned by FRD to create a permanent multi-screen video installation for a new ceramics gallery at the Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore. For more information, see garywarner.net, fieldwork.show and cdpmedia.com.au

Further reading

- Exhibition design company

- Virginia Gewin, The Washington Post, December 23, 2013

- Simon Gilby artist website

- stop-motion video of workshop construction

- Brad Norman is a Western Australian marine scientist and founder of ECOCEAN

- Site Architecture

- IUCN Red List

- Whale shark Wikipedia entry