Lisa Hilli, research of middi (shell collar) at Australian Museum 2012, photo: Yvonne Carrillo-Huffman

“When people claim their history, they write their history.” Opeta Alefaio

Re-connection

Several years ago I was told by an elder, Therese Kemelfield, from my community, to go and visit a museum collection store in Sydney. She told me there was a woman there called Taloi who I could contact to organise a visit. The entrance to the collection store was an unassuming door that led into a stairway. It was stark, sterile and had no sense of smell. The stairway had harsh concrete walls, fluorescent lights, with white painted handrails. There were multiple floors that we traversed to access the different levels. I felt completely disoriented and unsure if I was above or underground. Everything in the stores felt so dormant. I felt an immense urge to bring everything to life.

Established in 1827, the Australian Museum is custodian of approximately 60,000 ethnographic items from the Pacific region. My first experience of viewing such a vast number of historical items was overwhelming. I started my tour in the Micronesian and Polynesian collections. I remember seeing a huge slit gong drum, an instrument I was learning to play at the time with Papua New Guinean musician Airileke Ingram. I wanted to hear the sound and resonance of that huge drum. I knew exactly where to strike it to get the best sound. But I refrained from what my body wanted to do and just observed. I progressed to the Melanesian collections, the largest amount of material collected by the Australian Museum. Taloi Havini, an artist from the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, who worked at the museum, guided me through this culturally charged space. As we moved through the anthropologically labelled collections, Taloi made me aware of the different energy levels in each collecting area: Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia.

When we entered the Melanesian collections, we both sensed an energy shift. Taloi asked me “Did you feel that?” I nodded my head in agreement. I couldn’t wait to get to my cultural collection area of East New Britain. Taloi had strategically left it to last. We walked up and down the many aisles of shelves. They were up to three metres high and packed full of cultural remnants and fragments. It was information overload. There was so much history, so many beautiful things, so much knowledge and skill preserved in these stores.

Then I saw something. I saw tabu—shells that were unmistakably the same type that my people, the Tolai, use as a form of currency. But within this object, the shells were used differently. I knew that what I had found was something incredibly important. It was an object called midi (middi) or as the museum tag referred, “shell collar”. I didn’t understand what this object was and why it was here. I knew inherently by the design—a rounded oval shape adorned with hundreds of tabu shells— that it was worn over the head and sat on the chest area of the body.

My people the Gunantuna, or Tolai, are a cultural group that resides on the Gazelle Peninsular of East New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea. Historically, we migrated from the neighbouring province of New Ireland, a smaller sized island that lies adjacent to East New Britain. Apart from social pressures in our villages of New Ireland, it was the fertile volcanic soil on the island of New Britain that drew the Tolai people to migrate across the channel to what is now called the Gazelle Peninsula of New Britain.

Initiated Tolai men with their tubuans, kinavai ceremony, Rabaul, Papua New Guinea 2016, photo: Gideon Kakabin

The Tolai’s historical migration is symbolised in a re-enactment custom named kinavai. According to cultural historian and elder, Gideon Kakabin,“The kinavai ceremony is the fifth step in a series of cultural activities that the Gunantuna or Tolai perform to honour and thank their ancestors for having colonised and secured the land of New Britain in the distant past.” It is a re-enactment dance performed by initiated men and boys in canoes with their tubuans. A tubuan is a spirit symbol dressed in leaves, wearing a conical mask that is vividly decorated with traditional paints. Each design is unique to the tubuan and its clan. There are several references to the origin of the tubuan. One of these references tells of a story that two sisters were hiding in the bush, dancing and using tegete (dracaena or cordyline) leaves to adorn their bodies. Some men found the sisters, killed them and adapted their idea and created what has now become the Tubuan Society, a secret men’s union that forms a traditional government over the Tolai people.

The appearance of a tubuan is usually followed by a payment of tabu as a reward to the tubuan for having appeared. Tabu is Tolai shell currency and was initially known as diwara. The direct English translation of the word tabu is sacred. Tabu or Nassarius c.f Camelus shell are prepared by removing the humped tops and thread onto thin strips of cane in specific denominations. Tabu is of high importance to the Tolai and is a currency that is still in circulation today. The same shells that are used to make tabu are threaded with fibre around a strip of cane to make a midi.

I left the museum transformed. I wanted to know more. Why was this object here? How did it get here? Why didn’t I know that this object existed? Why didn’t my own Tolai mother know that this object existed? A multitude of questions emerged. I started having conversations with my late Uncle Peter Tukal, my mother’s brother, who lived the majority of his life on our madapai (motherland) village of Malakuna 04, approximately thirty kilometres from the volcanic region of Rabaul.

I was born on the same land as my Tolai mother in 1979. Two years after my birth, I migrated to Australia with my mother and siblings to be with our Australian father. In Tolai society, which is matrilineal, the brothers of a mother are considered father figures to her children. Similarly, I can call my mother’s biological sister/s “mother”, as we recognise maternal sister’s children being born of the same womb. Despite living in Australia, I had an extremely close relationship with my maternal Uncle Peter. He was highly respected and considered a “big man” in our village. He was also the peacemaker. After my experience of visiting a museum and finding this object called midi, I would often call on the telephone and tell him enthusiastically about the things I was looking at in museums in Australia. He would just laugh in happiness at my curiosity of wanting to know more about our culture. I asked for his guidance on the historical things I was able to access. Most importantly, I asked his permission to research this male body adornment, prior to starting my Masters Research in 2014.

Resistance

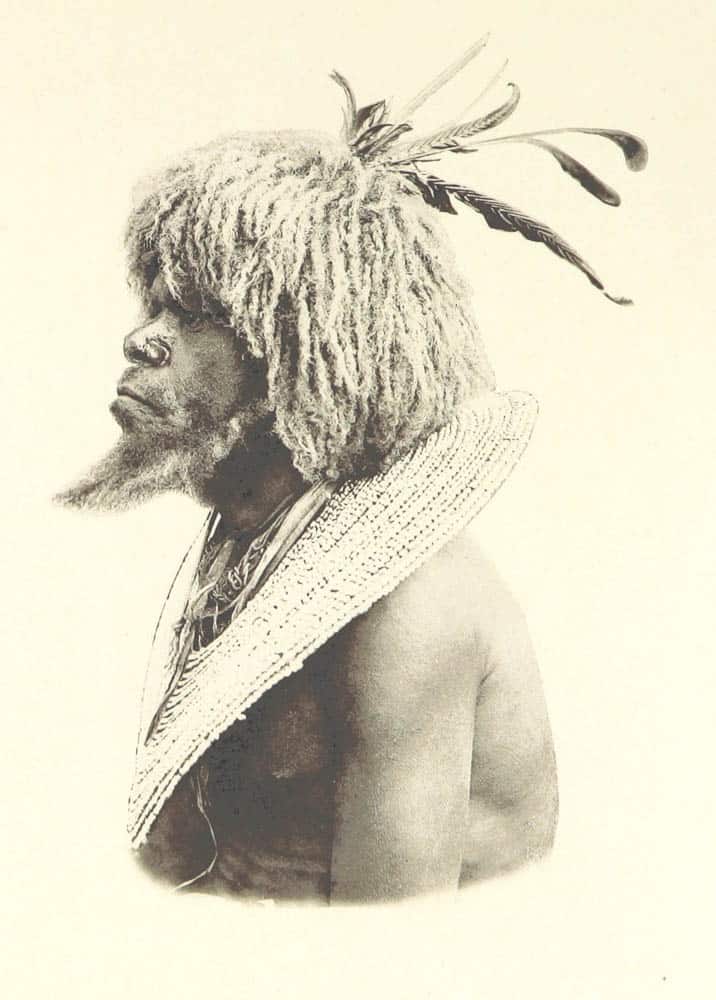

- Man named Turadawai wearing a midi, Gazelle Peninsular, New Britain, Papua New Guinea 1894. Image Adolf B. Meyer and R. Parkinson, Sourced British Library

- Man named Turadawai wearing a midi, Gazelle Peninsular, New Britain, Papua New Guinea 1894. Image Adolf B. Meyer and R. Parkinson, Sourced British Library

In late 2012 my mother and sister had scheduled my Uncle Peter’s first trip to Australia. I was beside myself with excitement, as was he. I was planning a trip to go to Sydney with him to view the midis that I had seen two years earlier. Exactly one week before my Uncle arrived, I started to smell smoke in the bedroom of my home in Narrm (Melbourne). It woke me up consecutively over several nights. I knew immediately that this was something spiritual. I didn’t know what it represented, but it kept waking me from my sleep at around two in the morning. I remember getting up to check outside to see if anyone was burning a fire. The smell of the smoke was very distinct; it was the smoke from my village, a smoke that smells of burning coconut shells, a common and plentiful fuel to cook food.

I acknowledged privately to myself what I experienced and didn’t mention it to anyone. A few days after my Uncle Peter arrived in Australia, he unexpectedly passed away at my mother’s home in Meanjin, Brisbane. I was emotionally shattered. The grief I felt was immense. When my sister called me to deliver the fateful news I had difficulty breathing. I completely withdrew socially as the shock of his death utterly overwhelmed me. So I travelled to Meanjin to be with my family. When I walked into the bedroom that my Uncle had been sleeping in, I noticed the same smell that I had experienced a week earlier. It was the smell of the smoke from the village that he carried with him, imbued with his bodily smell and within the clothes he packed and wore. It all made sense.

Dealing with my uncle’s death emotionally was intangibly heavy. It completely eradicated any cynicism I held toward spirituality in my culture. I began to better understand specific mourning rituals in Papua New Guinea, in particular the significance of the baja (mourning vest) and caps that the women from Oro Province wear after several months of seclusion, which I had seen in museum collections. These vests are intricately made garments in the shape of a sleeveless shirt. They are ornamented and interwoven entirely from thousands of Jobs-tears seeds strung on natural fibre, similar to beadwork. When worn, these vests and cap physically embody the intangible weight one feels whilst in deep grief. My uncle Peter was someone I was hoping to use as cultural support whilst undertaking my research degree. I knew that by going into a Western institution and my experiences of studying a previous fine arts degree, I would miss the cultural guidance and critique that I needed, particularly with my research focus on a culturally significant and historical item.

The issue of my gender and researching a male body adornment was raised continually throughout and beyond my degree. I felt frustrated that as an Indigenous Tolai woman, I had to validate myself in an academic context, and to a mostly white peer research community, that I had cultural permission to undertake this research. Historically, midi were culturally devalued through the onset of European contact in 1875, these “shell collars” were of interest to many foreigners that arrived on the shores of Rabaul as collectable items. The Pitt Rivers Museum states that “as early as 1906, a visitor to New Britain noted that these collars were no longer made, and that a collector would have to be lucky to obtain one in good condition, and only for a high price”. The only midi that remain today are stored in museums outside of Papua New Guinea.

In my homeland and the Pacific region more broadly, it is integral for us as a community and individuals to know whom we are related to, both living and deceased. Whenever I go back to Papua New Guinea, people always ask, who are my family? Who are my parents and grandparents and which area or village I am from? Indigenous people need to be able to place each other socially and geographically in order to understand who they are and where they fit in society. Undertaking research in Papua New Guinea as a mixed-race woman, without the presence of my mother, had its moments of difficulty. One very senior male Tolai elder chose not to participate in my research, which ethically I supported. He spoke to me and my family members that were present in a way that made me feel inferior. I couldn’t help but wonder if my gender and cultural standing had anything to do with it.

Remaking

I was strongly supported throughout my research journey by my primary supervisor Peter Cripps, a highly-regarded Australian sculpture artist. The first time I met Peter, he was standing out the front of the sculpture department at RMIT University in Melbourne. He was waiting to greet me—an act of physical sincerity. It was something I hadn’t come across before in academic life.

Peter was of a similar age to my late uncle, had short silver-white hair, wore black- framed glasses and was warm in his greeting. After our initial meeting, I felt I was in the right hands to undertake a serious enquiry of this object that had left me mesmerised four years earlier. Working under the tutelage of Peter proved ideal, given his breadth of knowledge and understanding of the relationship that materiality has to the body. I knew very early on that Peter wanted me to achieve the best I could and at times he challenged and pushed me to my limits, creatively and personally. He was particularly sensitive to the difficulties I faced within my research, including personal challenges I had in life as a sole parent. Despite not having my late uncle Peter to support me, a fellow Papua New Guinean friend, who is from the Gulf Region of Papua New Guinea, said to me during a conversation that her people believed that ancestors come back through people with white hair. I think the replication of names was enough for me to believe this. My late Uncle was still here supporting me; he just had lighter skin and hair.

- Underside of midi in progress, 2015, photo: Lisa Hilli

- Prepared nassa shells, 2014, photo: Lisa Hilli

- Midi first form (kalamanagunan), 2015, photo: Lisa Hilli

The core aim of my research was to remake a midi, a huge task to undertake alone. It took several months and a laborious amount of repetitious work. My preparations of remaking this historical object go back to the year 2012, when I was in the Solomon Islands during the Eleventh Festival of Pacific Arts. I knew back then that I wanted to make a midi and I needed to get the right shells. Historically the shells required to make tabu were traded on sea voyages with the Nakanai people who reside in West New Britain. Today the shells are traded through the hands of Solomon Islands people, who also have a shell currency system. I paid a woman at a market stall in Honiara the equivalent of eighty Australian dollars for approximately one and a half kilograms of shells strung on about four to five metres of string. I was not only paying for the shells, I was paying for the time it took her to collect the hundreds of tiny shells off the beach or estuarine, punch a hole in each shell and thread it on string. It’s the same labour that goes into the making of tabu, which is what creates the value.

I relied heavily on my own understanding of weaving methods accumulated over the last four years of my practice and used documented photographs that I took of a dishevelled midi, held in the Australian Museum. Apart from being geographically removed from the majority of my community who reside primarily in East New Britain, Port Moresby and Meanjin Brisbane, I had no knowledge of persons who knew how to make this historical object. The documented photographs that I took were all that I had. They allowed me to see the structure and understand the method of re-making a midi.

My first task was preparing the hundreds of shells. From my examination of the shells used within historical midis, the same preparation of the shells applied as for the making of tabu. Each tiny shell, no bigger than one centimetre, needed their shell-humps removed to be threaded onto fibre. As mundane as it was, I kept thinking about how manually heavy tasks, like the preparation of food in my community, were never done alone. Everyone helped. Next was the preparation of the cane, which would be the structural frame of the midi. I sourced extremely long lengths of cane and softened and shaped them by plunging them into boiling hot water for a short period of time, a technique my supervisor Peter taught me. When plunged into hot water, the heat softens the resin within the wood and allows the fibre to stretch and be shaped. A similar process is used for the classically named Bentwood Chairs, where pieces of wood are inserted into steel tubes that contain a constant flow of steam. I shaped a continuous three-metre length of cane into overlapping circles, ready to be woven around.

The fibre used to thread each shell to be bound around the cane within a midi was a type of sinnet made from an organic material, which I later learned is a fibre that grows inside the trunk of a specific coconut palm tree. To create the sinnet, fine threads are rolled and twisted together, usually on the thigh of the leg, or twisted between the fingers. I had to be realistic about the economy of time in making this object within my research project and decided that I had enough work on my plate. I began to trial different ready-made fibres such as cotton, raffia, and jute. Jute was the closest, strongest and most natural looking material that replicated the fibre within the design of a midi.

Threading the first prepared shell onto fibre and binding it around the prepared cane was a day of happiness. Whilst I worked, I had before me a historical photographic image of a man called Turadawai, whose name I later discovered. He is wearing one the largest midis I’ve ever seen. Adolf Meyer and Richard Parkinson published this image in an 1894 photo album in Dresden, Germany titled Album von Papua Typen und Bismark Archipel. Etwa 600 Abbilldungen auf 54 Tafeln in Lichtdruck. It’s photographed in true ethnographic portrait style: white sheet as a backdrop and an uneasy gaze from the Tolai man in view. He has a rabong (men’s basket) made of woven coconut palm leaves slung over his shoulder, an impressive amount of blonde-light coloured Afro hair with a tall adornment on the top of his head. At the bottom of the image, you can just see that he is wearing a leather belt and buckle that is securing a piece of plain European fabric wrapped around his waist or what is called a ”laplap” in Pidgin English. This image of Turadawai wearing a midi was a constant muse and reference throughout the culmination of making a midi and understanding its significance, superficially at least.

As I began to get into a rhythm of threading, binding and maintaining tension with the fibre being wrapped around the cane, I started to think about the men who may have made this majestic object. I imagined them in the tropical environment of my homeland, the intermittent sound of the cicadas, the steaming humidity releasing the fragrance of frangipani flowers and the conversations that are had in social work environments that I had experienced many times from trips to Rabaul.

I happened to have some of my own tabu that was given to me at funeral ceremonies that I attended. A loloi is a large circular bound shape made from of millions of shells strung on cane. This vast amount of tabu is considered a cultural investment in Tolai society; they are only broken and dispersed at funerals. I wanted to include my own tabu within this midi, which potentially would have been circulated and traded reciprocally through wedding and death ceremonies, initiations, and other goods and services.

The shells from the Solomon Islands, which I was embedding within the midi, were new. I wanted to imbue old history within this object, given the majority of shells I was using were new and uncirculated. As I stripped the tabu cane of its shells and threaded it onto the midi, I noticed something remarkable. The shells used to make tabu were larger in scale to the shells used to make a midi. Large Nassa shells are required to make tabu, as the width of the cane that is prepared for the shell to be threaded onto requires a larger hole, which is created with the removal of the shell’s hump. I had chosen smaller shells to thread onto the midi as the fibre was fine enough to thread through the smaller holes.

Not every single shell prepared can be threaded onto cane to make tabu. What then happens to the remainder of the disused prepared shells? Given that tabu is so highly valued, I came to believe that these smaller shells were then used in the application of a midi, rather than discarding them. When I undertook research in Rabaul in 2015, most Tolai people did not recognise this word midi. Nidi, a closely associated word means small shell. I couldn’t help but wonder if this was a colonial or European mistranslation as is sometimes evident in the vast archives of museums relating to Indigenous culture. Another note in the archives that I discovered was that midi were imbued with magical powers and gave protection to the wearer during warfare. More recent research through a Museums Victoria Scholarship in 2016 confirmed my discovery of the appropriation of tabu shells in a Kuanua Dictionary authored and published by the Australian Methodist Overseas Mission in 1964. I found the word Midi in this dictionary defined as the following;

Midi n. (1) Tabu, the shells of which are very small and consequently will not pass as money. (2) A wide collar covered with such shells

Given that this was the first midi to be made in over one hundred years, I made a decision to alter the design of the midi to reference the tabu system of currency continually being circulated. Most midis are made up of a range of 10–16 rows of cane ornamented by shells, gathered and secured at the top, which sits on the body. The gathered and bound cane strands sit at rear of the neck. I chose to make this midi a continuous circle, referencing continuation of culture and the reciprocal cycle of the shells embedded within the design. Trying to ascertain the significance and history of this object began with the meaning of the word. In the middle of making the midi I travelled to Meanjin, where there is a larger Tolai community, to spend time with my mother.

Aware of my own experience and physical reaction to seeing this object in a museum, I purposely worked on this object in my mother’s home in order to elicit a discussion about it with members of the Tolai community, who often dropped in to visit. An elder Tolai woman and man shared the following with me: the word “middi” means to thread or weave a pattern. They also said that “middi” is a word from the old language. I interpreted this as a word from one of several dialects in Tolai language that were used prior to European contact. I was low on prepared shells, so I asked my family to help prepare another batch of a hundred or so shells to be threaded. They all took turns in crushing the tiny humps on the shells, in the same crude way I utilised with flat nosed pliers. This act of collective labour was another continuation of culture.

By November 2014, I had woven hundreds of shells around a continuous length of cane, extended in one section only, to give me an approximate length of six metres, which sat in a loose coil. I now needed to bind all the loose bands of cane together to form the unique circular shape of a midi. It was during this time I attended closely to detail in the documented photographs that showed the underside of the midi, which revealed its true structure concealed by the shells on the front. The multiple strands of cane were linked and twisted together with fibre to hold the consecutive rows of cane in place and in line with each other. The tension of this linking of cane through fibre was crucial in getting the right form.

I was so determined in making this object that my physical energy was transferred into a form that was rigid and un-wearable. In fact, the midi looked like the shape of Kalamanagunan or Vulcan, a large volcano that rose up out of the ocean during the 1937 volcanic eruption in Rabaul harbour. Kalamanagunan in my language of Kuanua means “new place”. My bubu (grandmother) was a young girl when this volcano erupted out of the ocean.

The harbour of Rabaul lies on the north-eastern tip of the Gazelle Peninsular. On one side of the harbour are two extinct volcanoes, known as the Mother and Daughter. Directly in front of these two extinct volcanoes is a third active volcano named Tavurvur. My bubu told me a story about the cataclysmic activity that happened in the 1937 eruption. It’s quite common for earthquakes to occur during volcanic eruptions. Clouds of sulphuric gas and volcanic ash emitted can also trigger the creation of random lightning strikes. On this occasion, shifting tectonic plates impacted the sea level. My bubu said that the tide in Rabaul harbour receded so quickly that there were vast amounts of fish flapping about on the sand. The local villagers ran out to collect all the fish, moments later a tsunami wave came rushing back in and drowned those in its path. I later read the exact same story of the tide receding in the 1937 eruption explained in scientific and volcanology terms in a book published by historian Klaus Neumann.

I took my volcanic shaped midi to Queensland, this time to Bundjalung country (Gold Coast) to allow my elder brothers to wear it. During the making of the midi, it was imperative for me to continually try on the object whilst it was in progress, so that I could see how it sat on the body. Now that I had completed it, I needed to see how it sat on the body of a male. The midi I made has 16 rows of cane and is approximately 40 centimetres in diameter. It was an incredible sight to view all of the shells uniformly woven side by side without any break in the design. After seeing the midi on the bodies of my two elder brothers, who have varying body shapes, I noticed that it was sitting too stiffly and sat on the outer shoulder area. It wasn’t the right form. I undid the binding structure whilst I was there and relinked all the loose cane together again. Another failed attempt. I decided to leave the midi for the time being and enjoy the summer break with family.

I returned to Narrm, refreshed and rejuvenated. After two attempts at manipulating the form, I eventually surrendered to what the inevitable outcome would be. I released all expectations that I had placed upon myself for this object to be perfect on my first attempt of remaking it. I drew upon my own understanding of imperfections in life and art and looked at the photographs of the midis held in museum collections that I used for my own research. Each of these historical midis had subtle flaws of design and degeneration over time, yet the power of those historical objects still impacted me. This is the thought that I held onto.

- Midi final form 2015, photo: Lisa Hilli

- Installation view of midi, Lisa Hilli MFA by Research examination exhibition, School of Art Gallery, RMIT University, 2016, photo: Keelan O’Hehir.

I set myself up at a desk in my bedroom and photographed the midi before I disassembled it again for a third time. I turned the loose coils of cane to the underside and began this time to listen and physically sense the material itself, where it wanted to sit and be shaped. I relinquished my desire to shape it in the way I thought it needed to be and instead allowed the cane and fibre to guide me. It was a calm and clarifying process. I undid the structure of the former volcanic shape mid-morning and by the afternoon I had a softer, more contoured form that sat on the body, perfectly.

For the time being, I left on the threads that were used to form the structure. I placed the midi on my body and photographed myself wearing it. It was a private and profound achievement, which as an artist helped me understand the term “embodied knowledge”. It was at this moment that I felt as though I was finally able to understand and communicate with this historical object through my hands. Since seeing the first midi in the museum several years before, all I wanted to do was to try it on, to feel the weight and essence of time and history imbued in this object. Finally, I had achieved that feeling and desire. I captured the moment of this realisation, along with the knowledge of a skill that had been lost through the completion of remaking this object.

Re-activating

- Damien Kereku wearing a midi made by Lisa Hilli in 2015. Damien is standing on his land at Matupit, Rabaul, Papua New Guinea, photo Lisa Hilli

- Damien Kereku, Vunalagir vunatarai, Tolai people, 2015, photo: Lisa Hilli

- Lisa Hilli ceremonially presents a Middi to George Telek at the Museums Victoria launch of the multimedia installation and exhibition a Bit na Ta (the source of the sea): The Story of the Gunantuna, photo: Andy Drewit, Source Museums Victoria

- George Telek performing at the Museums Victoria launch of the multimedia installation and exhibition a Bit na Ta (the source of the sea): The Story of the Gunantuna, photo: Andy Drewit, Source Museums Victoria

In June 2015, I took the midi back home to Rabaul. It was a research trip to gain an understanding of the historical significance of midi and contextualise the object today. During my time there I was strongly supported by my family, in particular my Uncle Ivan and his wife Cinta. It was through a chance meeting that I was given an opportunity to speak to and photograph a highly regarded Tolai elder, Damien Kereku. Damien was a previous political ambassador for Papua New Guinea and former chairman of the 1960’s Tolai Indigenous political movement called Mataungans (Watch Out!). According to Bishop, Schütte and Jones (1972), The Mataungan Association is a “grass roots, village based, economic, cultural and political movement toward self-directed progress of the Tolai people of the Gazelle Peninsular, New Britain”. The Mataungan Association were pivotal in leading the resistance against the Australian administration and its political and economic systems within Rabaul, which influenced and motivated other political movements within the Australian Territory, eventually leading to Papua New Guinea’s independence from Australia in 1975. From the conversations I had with elders including Damien, I realised that the former chiefs or leading men in Tolai society prior to colonisation, who would’ve worn midi and other adornments of status, had evolved from warriors to modern day political activists and leaders against a century of German, British and Australian colonial rule. Returning this object back to the body helped me understand its physical effect upon the wearer and how wearing a midi forces the wearer to assume a body posture, that emanates strength, pride and status.

Historically the photographic depiction of Indigenous people, including the Tolai has largely been rendered invisible through little or no documentation of the full name and status of the person in profile. Many of the archival images I came across of Papua New Guinean people in archives are usually labelled as native, house-boy, plantation worker or only their first names are recorded, if at all. The historical image of a man named only as Turadawai, wearing a substantially sized midi, was the motivation for ensuring that the identity of Tolai people is known. Given this photographic history, I chose to name each photograph of Tolai people within my research with their full names, including their vunatarai (matrilineal clan). Essentially, I am implementing and reinforcing an Indigenous matrilineal knowledge system that Tolai people know, understand and are able to identify with.

In 1992 Kalamanagunan and Tavurvur furiously awakened, simultaneously devastating the town of Rabaul in a blanket of thick grey ash. Tavurvur has remained active to this day. Damien commended my remaking of the midi and remarked, “it was very well made.” I photographed Damien wearing the midi on his land at Matupit, with Tavurvur close by in the background. Prior to Damien, I had photographed this midi on the body of a Tolai male elder, Pearson Vetuna, who is highly respected within the Papua New Guinean community in Narrm.

I came to realise that these events of documenting and photographing Tolai men wearing the midi were “activations”. Another activation of the wearing of the midi took place in 2016 through celebrated Tolai musician George Telek, part of the Queensland Art Gallery exhibition No 1 Neighbour: Art in Papua New Guinea 1966-2016. Gideon Kakabin requested that Telek should wear the midi I had made as part of his musical performance with long-time collaborator David Bridie. The same activation of George wearing the midi took place again more recently at Bunjilaka, Melbourne Museum for the presentation of a Bit na Ta: Story of the Gunanatuna in September 2017. I’m not sure what the experience is for the men who wear the midi that I’ve made. I know that when I see Tolai men wear this incredible object, I feel a sense of fulfilment that I have revived a significant aspect of my culture that was brutally transformed and rendered insignificant through religious and colonial impact. Objects made for the body have the power to transform, signify identity, status and bring protection to the wearer. Through my research, I realised the midi embodies all of this.

Objects that were historically collected are rich sites for cultural engagement and renewal, but they are limited and fragmented without the people that create and understand the inherent knowledge contained within them. Much like the volcanoes of my homeland, the midi has lain dormant in the collection stores of museums for many years and through this remaking is once again being activated on the land and on the bodies of the people that it originated from.

Placenames

Gunantuna is the proper name for the Tolai tribe. Gunantuna is composed of two words: Gunan – place, land, village and Tuna – true. Gunantuna means true people or real people

Kuanua is the language of the Tolai people. It can also be referred to as a Tinata Tuna

Meanjin is the Turrbal People’s name for Brisbane.

Narrm is the name given to country around Port Philip Bay in the Boon Wurrung and Woi Wurrung languages. Personal communication with Stacie Piper (Wurundjeri woman) September 20th 2017

Further reading

Bishop, Rod; Schütte, Heinz; Jones, D.B, Mataungan: A Film on “development” and the Tolai people of Niugini, Cineaste, 1st July 1972 Vol5 (3) pp54

Hilli, Lisa, Regenerating Pacific Cultural Identity, Oceania Now, Issue 1,ed. Léuli Eshragi, Contemporary Pacific Arts Festival and Victoria University, 2015

Kakabin, Gideon, A Kinavai, Una Voce, Journal of the Papua New Guinea Association Australia Inc, No 1, March 2016. Gideon notes:.

Methodist Overseas Mission, New Guinea District, A Kuanua Dictionary, Methodist Mission Press, Rabaul, New Britain, T.N.G 1964. Note: Much of the translations in this publication was undertaken by Reverend R.H Rickard and Reverend Benjamin Danks between 1882 – 1893

Author

Lisa Hilli is a contemporary artist living in Narrm Australia. Born in Rabaul, Lisa is a descendent of the Makurategete Vunatarai (clan), Tolai people of Papua New Guinea. In 2016 Lisa received a Masters of Fine Art by Research degree from RMIT University and was also awarded a Museums Victoria 1854 Scholarship to undertake a research project in Australian museums and archives. Lisa’s work has been presented at the Queensland Art Gallery, Melbourne Museum and internationally at Framer Framed Tolhuistuin Amsterdam, Indonesian Contemporary Art Network and BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts Brussels. She has been an artist in residence at the Australian Tapestry Workshop and was awarded a photographic prize from the Centre for Contemporary Photography. Lisa is currently employed as a Collection Manager, Indigenous Collections and member of the Pacific Advisory Group for Museums Victoria. See her website www.lisahilli.com.

Lisa Hilli is a contemporary artist living in Narrm Australia. Born in Rabaul, Lisa is a descendent of the Makurategete Vunatarai (clan), Tolai people of Papua New Guinea. In 2016 Lisa received a Masters of Fine Art by Research degree from RMIT University and was also awarded a Museums Victoria 1854 Scholarship to undertake a research project in Australian museums and archives. Lisa’s work has been presented at the Queensland Art Gallery, Melbourne Museum and internationally at Framer Framed Tolhuistuin Amsterdam, Indonesian Contemporary Art Network and BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts Brussels. She has been an artist in residence at the Australian Tapestry Workshop and was awarded a photographic prize from the Centre for Contemporary Photography. Lisa is currently employed as a Collection Manager, Indigenous Collections and member of the Pacific Advisory Group for Museums Victoria. See her website www.lisahilli.com.

Comments

How beautifully you have woven the story of your people, your family and the colonist history that many white Australians find so unbearable. The midi is glorious but it is the weaving and stories that really make me cry. My Bunwurrang people, who you acknowledge in your text (thank you), are working to rebuild our disrupted lives and Land, most recently through our Muna Women project which is based around exactly the activities you describe as you wove the midi. My cultural experience was formed over the last fifty years in remote Aboriginal communities in the Pilbara and Arnhemland and the weaving fibres and methods are so familiar to me. I’m living in Geraldton WA but come regularly to Narrm for cultural business. I reckon you’d enjoy our Muna Women network, which is for First Nations women living on Narrm. I’ll contact you on Linked In if you’d like to chat with an old Aunty one of these days.

Brilliant Work Lisa. Thoroughly enjoyed it!