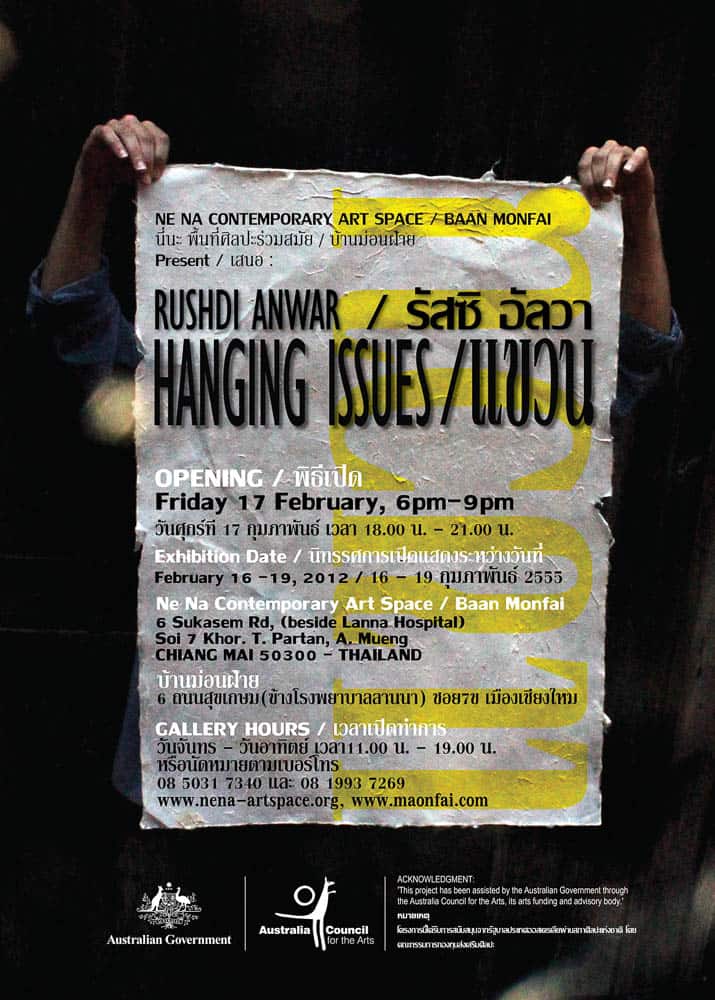

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, 2010, Ne Na Contemporary Art Space/Baan Monfai, Chiang Mai, Thailand, Opening night.

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, 2010, A traditional and contemporary Lanna dance was choreographed by Ajarn Rampad for the opening night, Ne Na Contemporary Art Space/Baan Monfai, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, 2010, Ne Na Contemporary Art Space/Baan Monfai, Chiang Mai, Thailand

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, 2010, Idin Paper Mill with professional master Thai paper-maker Khon ‘Supan Promseu’ in Muang- Lampang, Thailand

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, 2010, the process of making the paper at the Preservation House Paper Mill and craft in Ban Ton Pao – Chiang Mai – Thailand

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, 2010, Ne Na Contemporary Art Space/Baan Monfai, Chiang Mai, Thailand, installation view

This series Hanging Issues was developed during the time I spent in Thailand in 2012, when I undertook an art residency in Ne Na Contemporary Art Space / Baan Monfai Culture Centre in Chiang Mai, Thailand. It evolved from a body of work entitled The Few Lines of History 2011, photo installations that were developed during my study in the MFA Program at RMIT University in 2010. This work was created in response to social and political unrest in the recent history of Kurdistan. It examined how contemporary political events manifest in societies, which are facing turbulence in all aspects of life. The work explored how this unrest directly or indirectly reflects and impacts on the individual within that society.

The title Hanging Issues is a play on words. It refers to: (1) the physical installation of the works, which comprises of 60 photographic panels hung onto six parallel clothes lines; (2) unsolved political issues that are still in a state of lingering (i.e. Hanging Parliament); (3) the action of punishing someone to death through the action of hanging; (4) “hang somebody out to dry”, to leave somebody to struggle through a bad situation without support.

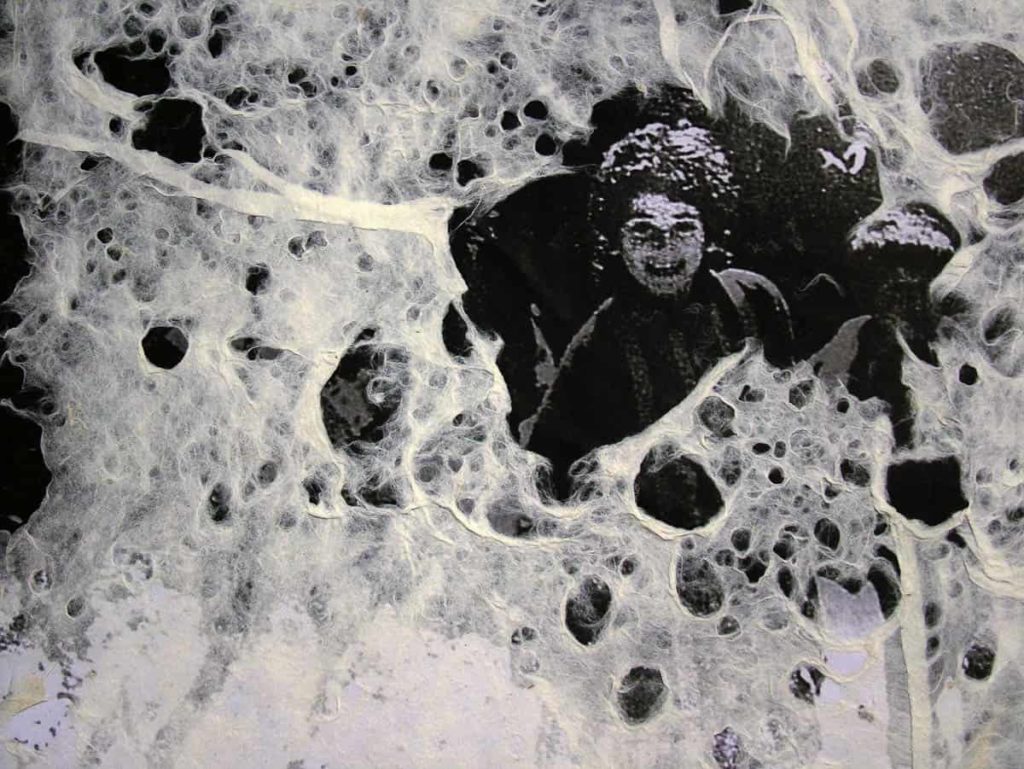

Hanging Issues consists of 60 panels of documentary photographs embedded in handmade Thai Paper (Kada Saa). Each panel contains a segment of a printed documentary photograph of political events related to the recent political history of Kurdistan. I embedded these within the Kada Saa paper in an attempt to evoke a sense of the many layers of issues.

The photographs in the work are all taken by me. One group are re-photographed images sourced from public news footage and mass media that depict a range of political events in Kurdistan from the 1970s-1990s. I cropped them to frame just the faces of individuals in the original news images, so that they became like close-up portraits. This enabled closer examination of their facial expressions that were a record of their shock and uncertainty about their futures: “The human power to survive and seek for hope”.

The subject matter of the other group of images depicts broken fragments of statues of the Buddha, including details of hands and feet of these statues. I took these photographs in the city Ayutthaya while I was on residency in Thailand in 2012.

The photographs that were sourced from the media emotionally captivated me. They evoked memories of my childhood during the conflicts in my homeland. I want to address the fact that these political issues from the past continue into the present day in different forms and events—history is continuously repeating itself.

Hanging Issues reveals the complicated issues of political events, offering so many perspectives on what it is to live in a conflict zone, and as a consequence to inherit difficult issues that must be dealt with through history. It aims to be an emotional experience. It deals with sensitive moments in political history, touching moments of suffering and hostility, and beautiful moments of survival and renewal. The project contains works that do have redemption, and they do have a bright side. They offer a sense of opportunity beyond errors of the past or the conflicts of the present.

I attempted in this project to create a connection between viewer and subject matter, between past and present, by bringing together photography and materiality of paper, texture, mark-making to address and to highlight the subjectivity of photography and the objectivity of paper.

The works in this project consist of photographic images that reference the past history, but in a way that is relevant to the present. The context of the works still has a strong connection and continues into a political minefield of present time. The issues create bitterness. I try to unpack that content of bitterness and suffering and put them on display in poetic ways, in order to transform feelings from bitterness to fragility and care. This means I have to transform the image. I tested this by combining them with handmade paper. Handmade paper reveals the touch of the time of its making. As a material, it has a warm feeling, a delicacy and an apparent fragility.

I wanted to create the conversation between the photographic images as the subject matter with the papermaking process and the quality of paper surface. I challenged myself to find a way to bring together the printed photo with the materiality of paper. It was important to merge together both elements , rather than like collage or hard edges.

I wanted to combine the harsh reality of the issues prevalent in the documentary photographs with sensitivity and physical delicacy of material, in this case the traditional Thai Kada Saa paper. I used the paper as a metaphor for recovery, gentleness and care. As Frederick Palmer writes, “Materials have a surface quality which we call texture. This quality we experience both by looking and feeling”.

I embedded the photographs between two layers of paper pulp. This pulp was extremely delicate and fragile. The photographs were concealed between the layers of pulp—in order to reveal parts of the images I applied water with pressure, which caused parts of the paper pulp to tear. The image was revealed between the broken layers of paper pulp. This technique—of concealing and revealing parts of the image—became a metaphor for how individuals’ stories have been hidden because of political motives in history. The process is also a metaphor for how the skin may react to exposure from a bullet or an explosion in conflict zones.

My goals in this project were the integration of material and image through the process of making in order to enhance the narrative and the concept of change. Also, I wished to investigate and seek to find the way to provide and facilitate integration of material as paper with photography and to employ the material’s physicality and the attributes of paper to highlight the subject matter of the photographs. Furthermore, it was important for both elements to be integrated and fused into each other in order to address the narrative and ethical issues of my story.I have addressed that through the use of the traditional Thai paper. That give

I have addressed that through the use of the traditional Thai paper, which enhances the fragile, sensual and temporary qualities. In addition, the project brought together the relationship between traditional hand papermaking of Lanna and a contemporary socio-political event of Kurdistan.

Although through the process of making the project, I have learned from local people about the history of Lanna Kingdom that went through instability time to time. It was fascinating to discover commonality in context of subject matter even in different times and locations.

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, 2010, the process of making the paper the deeper the frame is placed into the water, the higher quantity of pulp will be gathered leading to a thicker paper surface.

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, 2010, the process of making the skin of the Saa’s bark is peeled by hand and then dried out.

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, 2010, the process of making, the bark boiled in vats filled with water and ash or natural pigments.

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, 2010, the process of making, the pulp is dyed through the mill with synthetic colour

- Image No 11: Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, 2010, the process of making, traditionally, this process was undertaken by hand and pounded with natural pigments using wooden implements.

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, 2010, the Preservation House a Paper Mill and craft, Ban Ton Pao – Chiang Mai – Thailand

Learning the traditional Thai craft of papermaking gave me control over the effects and readings of the surface and textural quality of the works. The handmade Thai Kada Saa paper has a range of qualities, which could be described as; cratered, shattered, peeling, bumpy, porous, spongy and rough. Palmer again, “The graininess of such… is often used to express the feeling of dinginess in some badly lit subjects or to give a greater sense of urgency and violence to pictures of war and civil disorder”. The surface of the works aim to reference or evoke human skin as well as the perceived view of tumultuous political events.

I want to refer to them as human skins, how their skins are damaged and dreadful. For example, when I looked at some images from the places that had been attacked by gas and heavy weapons, the victim’s skins were extremely damaged as consequence of these attacks. The images revealed and were witnesses of inhuman and cruel attack. The surface references tragedy and damage. The society overcomes the tragedy, but the scar still remains. Furthermore, I wanted to utilise the paper characters as metaphor as scars on skin of history. The skin-like appearance is offset by the very visible texture of the paper characteristics.

I developed and gained the craft skill of papermaking in a traditional Thai manner. That has allowed me to infuse photography within paper without pinning or gluing, and create unique surface qualities, which enriched and invoke the theme of the project. I learnt it in Ban Ton Pao, which is a village in the Chiang Mai district well known for its quality saa paper products that have been produced here for many hundreds of years since Lanna Kingdom. Traditional Thai saa paper is made from the bark of the mulberry tree. Through a series of refined processes, the bark is transformed to produce a textured and delicate paper surface from the pulp, kada saa. I had the opportunity to learn the processes of making behind this ancient craft at Preservation House, a paper mill factory established by Khun Charaun and Khun Fongkhum Iapinta over 25 years ago.

The project was housed in an open space at Ne Na Contemporary Art Space in Chiang Mai, Thailand. The work was installed in open space in the courtyard of the Monfai Cultural Centre/ Living Museum. The courtyard was surrounded by a number of galleries which hold and display traditional Thai crafts, textiles and artworks. The size of the space (courtyard) where I had installed the work was approximately 120 x 80 m. The work merged with the characteristic elements of the space, which is traditional Lanna style architecture of northern Thailand. Even if the content of the installation was not site-specific, the work responded to the surrounding environments: with the slight breeze, the panels started gently to float.

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, (detail), 2012.

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, (detail), 2012.

- Rushdi Anwar, Hanging Issues, 2010, the process of making, the Preservation House a Paper Mill and craft, Ban Ton Pao – Chiang Mai – Thailand

The works were suspended with ordinary wooden clothes pegs, attached to six parallel clotheslines. The panels were displayed in zigzag layout. The space between each line was more than one metre and also there were one-metre gaps between each panel. The zigzag arrangement of the panels enabled the readings to work and build over time as in a procession. There was a strict formality about the format installation of the panels. This arrangement limits the spatial movement of the viewer, as they are required to pass close to the work and deal with content again and again, time after time. They are dealing with a continuing representation of a past event in the present during their passage through the work. However, the installation arrangement offered an opportunity for the viewer to investigate each image closely. I wanted the work to have a hovering presence in viewers’ space, evoking the sense of the past actions on the paper and of photographs becoming present as existing phenomena in the here and now.

The purpose of this zigzag layout format is to create an arena to display the works. It offers opportunity for the viewers to find themselves inside the work, to become a part of the work. They are not just passively standing and looking at the work, but they are also moving through it. Additionally, the installation format offered possibility for the viewer to engage with the work from different viewpoints. The hanging structure of the installation allowed the work to hover in the air. If one moves alongside the panels, they seem to gradually appear and disappear as they shift from rectangular planes to the vertical view of slight lines. The open-air installation permits the wind to gently move the images.

My goals in this project were the integration of material and image through the process of making in order to enhance the narrative and the concept of change. Also I wished to investigate and seek to find the way to provide and facilitate integration of material as paper with image as photo and to employ the material’s physicality and the attributes of paper to highlight the subject matter of the photographs. Furthermore it was important for both elements to be integrated and fused into each other in order to address the narrative and ethical issues of my story.

Further reading

Frederick Palmer, Visual Awareness London: Batsford, 1972

Author

Rushdi Anwar is a Melbourne-based artist originally from Kurdistan. His installation, sculptures, painting, photo-painting, and video works often reflect on the socio-political issues of the Middle East. This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council for the Arts, its arts funding and advisory body.

Rushdi Anwar is a Melbourne-based artist originally from Kurdistan. His installation, sculptures, painting, photo-painting, and video works often reflect on the socio-political issues of the Middle East. This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council for the Arts, its arts funding and advisory body.