I am a contemporary jeweller and a partner of Gray Street Workshop. I work predominately in metal and flamework glass. My work is influenced by nature, botanical specimens and memory. In my exhibition work I use nature as a metaphor to investigate concepts of the fragility and transience of memory. To me flowers are a constant reminder that life is ephemeral, ever changing, momentary and precious.

In 2014 I was granted an Asialink artist residency in Bangkok, Thailand, supported by Arts SA. It was a truly incredible experience, one which is enriching my practice.

Bill Bryson describes the glory of foreign travel is that you are reduced to a childlike state of wonder. You can’t read, you don’t understand what people are saying, you only have a rudimentary understanding of how things work, you can’t even cross the road without endangering your life. My own memories of my childhood are my most magical. Everything was a discovery, everything seemed amazing. So perhaps this is why that when I am travelling I feel so amazed, inspired, intrigued because I am reduced to a childlike state.

My residency took me all over Thailand. I was…

- molding cow dung in a remote village in the province of Ubon Ratachathani where I was casting bronze bells the same way that has been done for over 4000 years

- working with delicate orchids in the Museum of Floral culture

- threading hand-cut leaves in Pak Ret

- holding up traffic on a photo shoot in the streets of Bangkok and even a short ceramics residency at Tao Hong Tai in Ratchburi

But let me concentrate on the main focus of the residency: Phuang Malai.

Collection of photos from different locations around Thailand. Clockwise from top left: Ancient casting in Ubon Ratchathani, photo: Annelies Hofmeyr. Learning how to spin cotton, Ubon Ratchathani, photo: Annelies Hofmeyr. Threading orchids in Pak Kret, photo: Jess Dare. Phuang Malai at Pak Khlong Talat, photo: Jess Dare. Planting rice, bare foot in a village in the province of Ubon Ratchathani, photo: Annelies Hofmeyr. Slip casting in Ratchburi, photo: Jess Dare.

Out of respect for Thai culture, I will not speak as some sort of authority on Phuang Malai, but I would like to share some of my observations of these strings of flowers and the sequence of events that have brought me here.

It began with the development of my glass conceptual flowering plants, a series of fragile flamework glass plants created in memory of my grandfather, exploring the idea of the fragility of memory for my first major solo exhibition “The Nature of Memory” in 2013.

- Jess Dare, Conceptual Flowering Plant Series, 2013, Flamework glass, dimensions vary, Photo Grant Hancock.

- Jess Dare, Conceptual Flowering Plant Series, 2013, Flamework glass, dimensions vary, Photo Grant Hancock.

- Jess Dare, Conceptual Flowering Plant Series, 2013, Flamework glass, dimensions vary, Photo Grant Hancock.

After the exhibition had finished touring Adelaide, Sydney and Canberra and I had lugged these 22 fragile glass plants from state to state, I visited Thailand for a rest. I was captivated by the exotic tropical flowers, funny shaped fruits and beautiful flower garlands draped over shrines and statues.

When I returned to Australia I began researching Phuang Malai, which literally translates into “bunch garland”, an ephemeral craft employing different patterns and flowers for different meanings and occasions. I was instantly captivated by its form and one of its functions to honour “seen and unseen beings” alike, echoing the themes of memory and honouring past loved ones that is core to my exhibition work. But there was little information available in English, I repeatedly came across the exhibition Welcome Signs: Contemporary Interpretations of the Garland, curated by Kevin Murray, an exhibition exploring the way traditional garlands common in the Asia Pacific region are used to Welcome. The exhibition looked at the changing role of the garland from an ephemeral part of the ritual, to a keepsake to take home and how cultural traditions might be sustained despite displacement and urbanization. A variety of artists responded to the theme utilizing different materials and exploring different aspects of human connection. (Murray, 2010) I contacted a number of the Thai artist involved in this project, along with Atty Tantivit from ATTA Gallery and asked for her advice on contemporary jewellers and jewellery workshops in Thailand. I then set about applying to Asialink, an organization in Australia that helps fund approximately 30 artists per year to travel to Asian countries to undertake artist residencies.

My application was for a self-initiated Residency, skills and cultural exchange at Atelier Rudee in Bangkok, Thailand. Atelier Rudee is an International Academy of contemporary jewellery established in 2011 by Rudee Tancharoen, a contemporary jeweller who studied at Alchemia in Italy. The Atelier runs a variety of workshops, master classes and lectures set in the suburbs of Bangkok. It was a calm sanctuary and an inspiring place to work in.

The objective of the 10-week residency was to learn how to make Phuang Malai, to understand their significance, why certain flowers are used, how they are used and by whom and then to translate this research into my work.

Lesson in Pak Kret: image showing all the elements ready to assemble, (Malia, Uba, Malai Seek), 2014. Hand dyed Orchid petals, Crown flower, Jasmine. Photo: Jess Dare.

From one of the textbooks Rudee helped me translate, I learnt that Phuang Malai are flower petals and leaves put together with needle and thread and pulled into a circle shape, with different tassels or Uba which hang down from the Malai. (Kengjaroen, 2010)

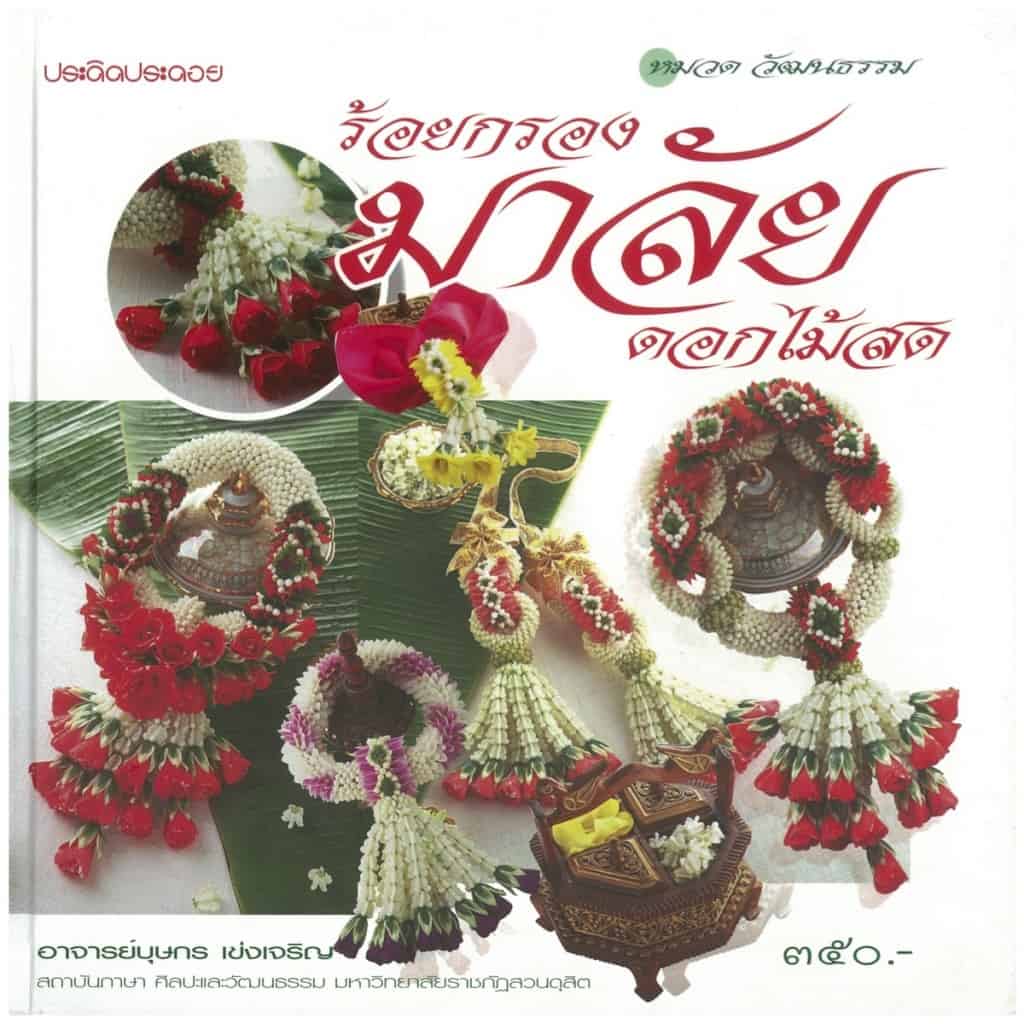

Compose fresh flower garland, a Text Book Rudee Tancharoen helped translate into English. (Kengjaroen, 2010)

There are several shapes and styles with a variety of functions that fall into the three main categories of offering, decoration and gift. The functions include offerings to Buddha or for hanging around the neck or the wrist or to hold in the hand. They can be tethered to boats, cars and buses for a safe journey home. There are types for ceremonies like wedding and funerals, whilst some simply hang in the windows of houses for scenting the breeze with jasmine. I was particularly interested in the role that they play in paying respect, and as offerings.

- Compose fresh flower garland, a Text Book Rudee Tancharoen helped translate into English. (Kengjaroen, 2010)

- Phuang Malai tethered to a mooring on the Bang Bao jetty, Koh Chang, Thailand, 2014. Photo: Jess Dare.

One of my teachers in Pak Ret told me anyone can make Phuang Malai, but not everyone can make beautiful Phuang Malai. To make beautiful Phuang Malai you must respect the following four elements: proportion, skill, colours and freshness of flowers. It takes great skill, firstly choosing similar size flowers and thus selecting similar size petals. If you are hand cutting the petals or leaves they should all be the same size and cut round with no sharp corners. You must have a consistent distance between the needle and the tip of the petal giving an even diameter, even spacing of the petals to create an even twist in the Malai. And the maker has to work ‘fine and calm’, which I can attest to, is a skill in itself.

Lesson in Pak Kret: Learning how to cut leaves and thread using long Phuang Malai needles. 2014. Photo: Jess Dare.

The freshness of the flowers is also key to the beauty of a Phuang Malai and I was also told you should not smell the Malai as the scent is reserved for the receiver. However with modernisation and the introduction of different materials such a fabric, paper, ribbon and plastic, this factor of freshness is no longer relevant in these forever bloom Malai.

Shop front at Pak Khlong Talat selling plastic and fabric Phuang Malai, pre-tied ribbons and plastic flowers. Thailand, 2014. Photo: Jess Dare.

Different flowers also hold different meanings. For example, the crown flower represents love whilst the amaranth represents never ending, so when used together they mean never ending love.

First traditional Phuang Malai I made using Jasmine, Crown flowers, Amaranth and Magnolia flowers. Together the crown flower and amaranth mean never ending love. Pak Kret, Thailand, 2014. Photo: Jess Dare.

I often spent hours at Pak Khlong Talat, Thailand’s largest flower market, photographing and watching the scores of Phuang Malai being made, blooms by the bag full being sold. Bags of Crown flowers for 100baht (less than 4 Australian dollars), amaranth for 30baht, marigolds for 20Baht.

- Bags of crown flowers being sold at Pak Khlong Talat (Flower Market). Bangkok, Thailand. 2014. Photo: Jess Dare.

- Phuang Malai being sold at Pak Khlong Talat (Flower Market). Bangkok, Thailand. 2014. Photo: Jess Dare.

My first experience making contemporary Phuang Malai was a master class with Khun Sakul Intakul, director of the Museum of Floral Culture in Bangkok.

Having grown up in Australia I was accustomed to seeing flowers as beautiful, whole things, arranged in vases. This is what Khun Sakul would describe as a “vase” culture. But in Thai floral art, flowers are deconstructed petal-by-petal and reconstructed in different formations and using individual petals as a raw material or design element. Sometimes even pulling apart one flower, cutting and manipulating the petals to form another type of flower, a sort of flower alchemy. I initially struggled pulling the flowers apart it actually felt somehow cruel to tear apart orchids, a rare and expensive commodity in Australia.

Lesson at Museum of Floral Culture, Bangkok Thailand: learning how to tie Dokkha (Fabricated flowers made from petals, held together by a thin thread, forming a lotus-like bud). Tapioca stem, Orchid petals and Jasmine. 2014. Photo: Jess Dare.

Khun Sakul kept saying, “Speed and precision Jess Dare, don’t disappoint me.” Pulling apart an orchid to use only one of its four different shaped petals was hard for me. I did it slowly and carefully trying not to bruise the petals. But when you are making something which potentially will perish in a day, if not a few hours, time is of the essence.

In a version of contemporary Yeb Bab, I used one particular shaped petal from 37 orchids, 37 Jasmine buds and a dissected amaranth flower, layered in a radial pattern.

Lesson at Museum of Floral Culture, Bangkok Thailand: learning how to tie Dokkha (Fabricated flowers made from petals, held together by a thin thread, forming a lotus-like bud). Tapioca stem, Orchid petals and Jasmine. 2014. Photo: Jess Dare.

The two most difficult things to comprehend were dismantling flowers and spending hours, even days making something that will perish within a day or two. The first traditional Phuang Malai that I made, I kept in the fridge for three weeks. I thought it was too beautiful to let wither and die. I couldn’t let go. By the end of the residency, I had Phuang Malai of all shapes, sizes and styles hanging from every conceivable hook, shelf and rail in my apartment, all slowly withering, fading and shrinking, the scent was beautiful, delicate and sweet.

I learnt traditional Phuang Malai each week in Pak Kret which is between one and four hours from central Bangkok (depending on traffic). I sat in countless taxis on those trips to Pak Kret observing the variable plethora of offerings filling the dashboard and suspended from the rear vision mirror. I started photographing these taxi amulets, trinkets and shrines, each taxi I stepped into there was another surprise on the dashboard waiting to be discovered.

I later met another artist in the BACC, Bangkok Art and Culture Centre called Dale Konstanz, who was presenting his exhibition Thai Taxi Talismans. It turns out he had been photographing Thai taxis since 2003 and published a book on the phenomenon called Thai Taxi Talismans; Bangkok from the passenger’s seat, in which he has an entire section called Taxi Flora (Konstanz, 2011). I had lots of these accidental meetings in Thailand. One thing led to the next. I followed peoples generous advice and ended up meeting some incredible artists and teachers.

I became more aware of my own sentimentality during the residency. I have always made work about memory and in a way my fear of forgetting. I hold people and memories dear. In the past I have made works to last, to stand the test of time, choosing traditional materials of metals and glass. From a foreigner or Farang’s perspective, I saw these beautiful garlands and wanted to somehow preserve them. However, this new form of making challenged this thinking. To spend hours making something that may only last another day was so foreign to me. Questioning whether the act of making was important as the work itself? To spend time and pour love into something that is offered to Buddha or loved one, past or present, is a simple and generous act, meditative and cathartic.

In Thailand I met Annelies Hofmeyr a South-African born (world-based) conceptual artist and we collaborated on a project towards the end of the residency. I created a series of Phuang Malai with the assistance of Annelies and we photographed them on a Thai model named Miss Nattawadee Prempree (Nicknamed Pew) around the streets of Bangkok, in everyday situations on the sky train (BTS), eating lunch in the market, chatting on her mobile waiting for a bus. The idea was a catalyst to talk about this traditional craft in this rapidly changing modern city.

Figure 18: Collaborative project with Annelies Hofmeyr. Bangna, Thailand. 2014. Photo Annelies Hofmeyr.

The two collections I have made since returning to Australia are for international travelling exhibitions which will be touring for two years, so for practical reasons the works are solid and enduring. But my aim now is to explore more ephemeral works using fresh flowers, considering the act of offering and impermanence.

I can’t tell you what the long-term effect will be on my work, as the experiences are still so fresh. But for now, my studio space is lined with photos of tropical plants, shrines and Phuang Malai, overlaid with forever blooms, collected trinkets and experiments. I think it is likely to take years for me to fully process the experience and respond respectfully to them.

Whilst researching my next residency in China later this year I came across the book Strange Flowers, Australia-China Encounters in writing and art, edited by Ronnie Scott in which Ouyang Yu speaks of “strange flowers that bloom when creative seeds are planted in foreign soil.” (ed. Scott, 2011)

These literary musings resonated with me, it felt like they were describing my own experience after planting myself, a seed in Thailand, and these strange flowers are now growing, and blooming in my work. The following works are my strange flowers, the immediate responses to the residency.

Upon return to Australia I was awarded an Australia Council New Work Grant to develop a new collection of work in response to the residency. This new work is in part being exhibited in Theatre of Detail, along with new works by founding partners of Gray Street Workshop Catherine Truman and Sue Lorraine to coincide with the Workshop’s 30-year anniversary celebrations.

The collection of work I have created is titled Offerings. They are highlighting the core construction principles of Phuang Malai; deconstruction, reconstruction, and proportion with reference to aspects of beauty, respect, honor and merit giving.

Elementary Phuang Malai is lifted from the pages of my sketchbooks, from instructions scribbled in my journal. I have reduced the components of the crown flowers to simple conical shapes, the globe amaranth to spheres and the magnolia or champee to four pointed petals. Using a white powder coated surface to reference the simple line drawings from my sketchbooks.

Jess Dare: Offerings: Elementary Phuang Malai, brass, copper, cotton thread. 2015. Photo: Grant Hancock.

Grand Gesture, a heavy brass garland which speaks of the important design and structural element of a beautiful Phuang Malai, the twist that the petals should form. Its polished brass is reminiscent of ritual objects and its heavy weight referencing the gravitas of a grand gesture.

Happy Birthday Dear King is a fictitious ceremonial gift Malai for the much loved King of Thailand. In Thailand each day of the week is represented by a colour. The King was born on a Monday and therefore his colour is yellow, hence the use of yellow candles and the flowers themselves are cast sterling silver birthday candleholders.

Jess Dare: Offerings: Happy Birthday Dear King, sterling silver, copper, birthday candles, steel. 2015. Photo: Grant Hancock.

Fading Yeb Bab is a wall installation made up of 13 white mandalas with hand stitched glass petals. Traditional Yeb Bab are decorative mandalas made of hand stitched petals and Jasmine buds onto banana leaves. I have simplified petal shapes and used white and clear glass, bleached of colour to suggest transience in the way flowers wither, loose colour and die. The title also references the fading out of this traditional craft. According to Rudee, Phuang Malai became popular during the rein of King Rama V (1868 to 1910) and traditionally all children were taught in schools how to make them. Now this is exceptional. Where once people would make them in their homes, they can now purchase them from street vendors, even driving down the busy streets, sellers dart between traffic yelling “Phuang Malai, Phuang Malai” and you can buy them for 10 to 20baht without even getting out of your car.

Jess Dare: Offerings: Fading Yeb Bab, brass, flamework glass, stainless steel, cotton thread. 2015. Photo: Grant Hancock.

Meditation Malai is a circle of repeated glass plant sprigs, a virtual garland, possible and impossible at the same time.

Remains of the Day is a collection of work I have created for Koru5, an exhibition in Finland. In Thailand I began photographing decaying Phuang Malai that I found in the street, their intended destination unknown to me, perhaps dropped, offered to a spirit house or temple, or strung on a car rear vision mirror. I was intrigued by the brilliant coloured ribbons and decaying, browning petals, flattened by passing traffic, shrivelling in the heat and wondered had these objects reached their intended destination. Someone took care to string these delicate petals and crown flowers together. I marvelled at the journey these objects had taken and what brought them to this place.

- Decaying Phuang Malai. Crown flowers, orchid, rose and cotton thread. Thailand, 2014. Photo Jess Dare.

- Jess Dare: Remains of the day: Phuang Malai series, powder coated brass, cotton thread. 2015. Photo: Grant Hancock.

These pieces are made of brass, powder coated and scratched back in parts. The colour white references decay and strands of cotton slowly undoing themselves hastening the passage of time, alluding to the disintegration and sun bleaching of the once brightly coloured ribbons. After a Phuang Malai is offered it will eventually decay leaving behind only the act of offering, these enduring objects represent this passage.

Jess Dare: Remains of the day: withering champee, powder coated brass, cotton thread. 2015. Photo: Grant Hancock.

I went to Bangkok with clear goals and objectives however my experiences were far richer than I hoped for. My journey took me all over Thailand, opened my eyes to another way of living, other ways of making, new techniques, new attitudes and ideas. I don’t fully understand the enormity and magnitude of what I have experienced or how it will affect my practice long-term. The residency was just the beginning and I can’t wait to see how it all unravels.

I feel incredibly privileged to have had these experiences, I feel truly inspired and excited about my practice. I actively chose to expand my vocabulary and my practice by travelling to another country to experience new skills and way of making, immerse myself in another culture. And I would encourage anyone to undertake an artist residency, to extend your physical borders, push your personal boundaries and comfort zone, challenge yourself, question your making, explore the unknown and then see what happens next….

Further Reading

Bryson, B. 1991. Neither Here nor There: Travels in Europe, Great Britain: Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd pp44

Kengjaroen, B. 2010. Roi-Krong-Ma-Lai-Dok-Mai-Sod [compose fresh flower garland], Bangkok: Somnakpimmaeban Co. pp15

Konstanz, D. 2011. Thai Taxi Talismans: Bangkok from the passenger seat, Bangkok: River Books Co.

Scott, R (ed) 2011. Strange Flowers: Australia – China encounters in writing an art, South Australia, Wakefield Press (abstract)

Murray, K. 2010. Welcome Signs: Contemporary Interpretations of the Garland. Available from: [23/04/2015]

XE Currency Converter, 2015, AUD exchange rate. Available from: <http://www.xe.com/currencyconverter/convert/?Amount=1&From=AUD&To=THB>. [12 June 2015]

This is an Asialink Arts Residency Project supported by Arts SA

Author

Jess Dare is a South Australian contemporary jeweller, glass flameworker and partner of Gray Street Workshop (Established 1985). This year Jess will be exhibiting in Germany, Finland, China, Thailand and New Zealand and is currently developing a collection of new work responding recent residencies in Thailand and China for a solo exhibition in 2017. Contemporary jeweller Jess Dare completed a Bachelor of Visual Arts in 2006. Since 2005 she has been practicing lampworking, having been taught by local and international glass artists, glass now forms an integral part of her practice. Dare joined Gray Street Workshop (Est.1985) as an access tenant in 2007 and in 2010 became a partner of the workshop, joining Catherine Truman and Sue Lorraine in continuing its legacy and shaping its future. Dare has exhibited nationally and internationally and is represented in major national collections including The National Gallery of Australia, the Art Gallery of South Australia and the National Glass Collection.

Comments

The passing and impermanency in buddhist cultures is a struggle for the westerners who strive to preserve it all.

Wow. I just had to write. I am on a trip to Bangkok as I write this, and I was trying to learn how to properly offer garlands at a shrine. My search led me to your article, Which I found amazing, I love flowers and have been secretly wishing that I could learn more about making the garlands. The jawdropping moment was when you mentioned Dale Konstanz! He was my composition and color theory professor at MIAD in 2002-03, and I graduated from there with a BFA in Painting in 2006! Maybe I’m just crazy, but it felt fateful that I should read this at this moment. I would love to hear more about this body of work, being an artist in Bangkok, and more tips for leaving the offerings. So happy that I came across this, and hopefully we can connect in the future!

Perhaps you can explain the significance of a string of flowers given to me by a Thai woman. The string is exactly like the picture just to the right of the above photo showing rice being planted. Roses at the end of a woven string of small delicate white bead type flowers. I had met and became interested in a Thai woman on my recent holiday and upon leaving to fly home, she presented me with this lovely gift. however, it’s true meaning escapes me. Thanks for your response.