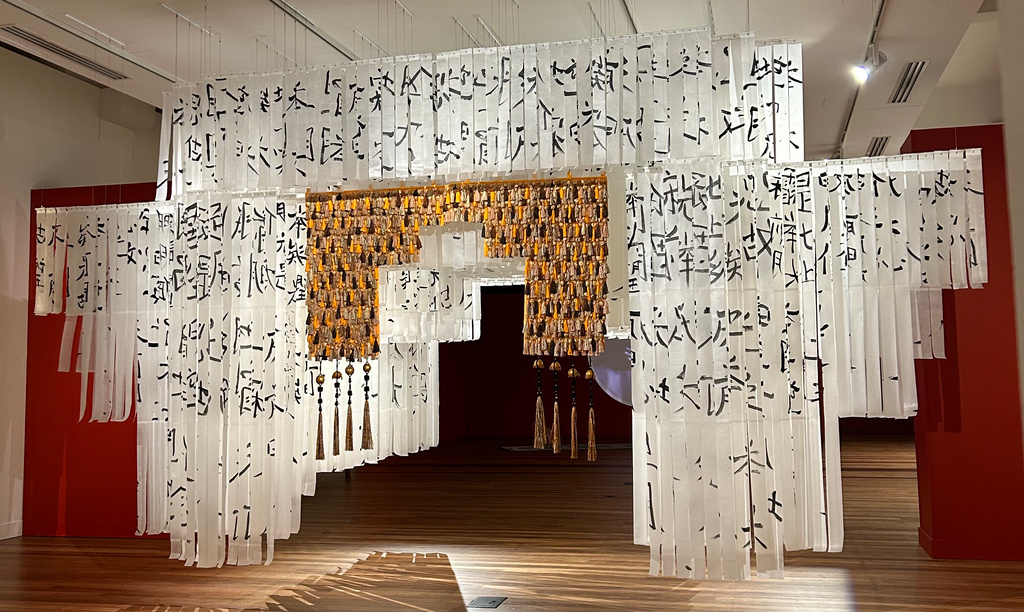

- Jacky Cheng, Imaginary Homelands installation, 2025, National Art School, Sydney

- Jacky Cheng, Imaginary Homelands installation, 2025, National Art School, Sydney

- Jacky Cheng, Imaginary Homelands installation, 2025, National Art School, Sydney

- Jacky Cheng, Imaginary Homelands installation, 2025, National Art School, Sydney

Jacky Cheng talks about the epic evolution of her Paifang gate, from dyeing workshops in Laos to a mother-daughter collaboration in Broome.

In 2024, Jacky Cheng was invited to participate in an exhibition, The Neighbour at the Gate, curated by Clothilde Bullen, Michael Do, and Zali Morgan. The exhibition aimed to “centre the connection between First Nations and Asian Australian cultural groups and also raise the level of awareness of those connections” that exist outside mainstream culture.

Three key provocations framed the project:

- How immigrants to Australia are both beneficiaries of and impacted by colonialism, and how to understand this.

- How Asian diaspora communities make meaning in a new land under colonialism, especially when new to understanding Australian First Nations peoples and their history and their entanglement with identity, nationalism, and post-colonial structures.

- The convergence of friendship, migration, and custodianship, and how stories of mobility, cultural interaction, and resistance intersect.

Jacky Cheng chose to respond literally to the idea of “the gate”, drawing inspiration from Salman Rushdie’s book, The Imaginary Homelands. She talks about the concept and realisation of her work.

✿

The Neighbour at the Gate leans into those feelings of being on the outside looking in. There’s this push and pull between longing for a place, feeling part of it, and also feeling slightly removed. I’m constantly circling it, remembering it, but never fully in it within my own community. I think that’s something many people experience, especially those who have been displaced or grown up between cultures.

This year is my twenty-fourth year in Australia, and I left Malaysia when I was twenty-four. I am at the equal time of as much time I’ve spent in Malaysia as I’ve spent in Australia. I am neither strong in either one, but I am trying to hold on to something. The word “the gate” really draws back to identity, belonging, and how memory can both comfort and complicate.

Paifang

One of the biggest references to Chinese gates is the paifang archways. They are simply beautiful and symbolic structures, and also act as a marker or a threshold between what’s known and what’s unknown. For someone like me from a migrant background, that idea of being in between worlds really resonates. The work was very much about welcoming people through these invisible borders, because we go through so many invisible borders or invisible gates everywhere we go.

The wording on the Chinese paifang would usually be about something that relates to prosperity. And then there will be lots of different symbols associated with that. You typically see a bat or two lions, though for my work, it’s not about the lions; it’s essentially experiential when moving through a physical archway.

The height of a gate must be grandiose…

The height of a gate must be grandiose, which I tried to encapsulate. It’s not a small gallery, but by the time the gate goes up, it has given the space a presence, and you have no choice but to be drawn to go through. It’s the difference between profane and sacred, moving into some different, more sacred space.

How the work was made

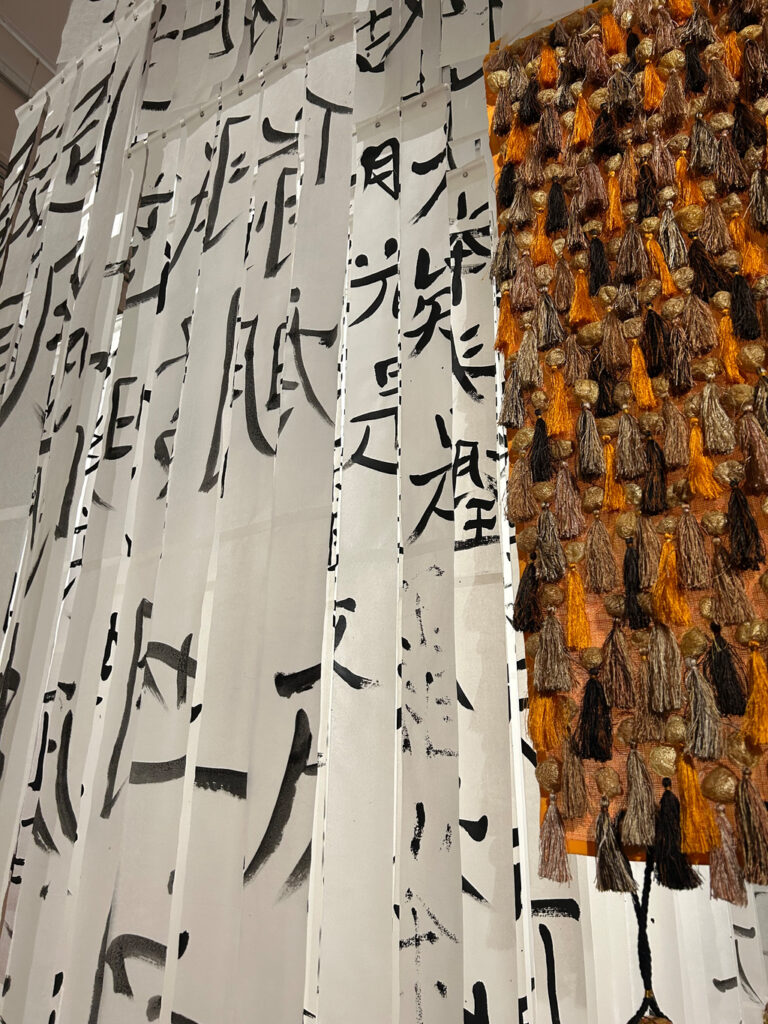

Earlier this year, I went to Laos, and I did a workshop with Samorn Sanixay on natural dyeing. I’ve heard great reviews about what Samorn has done within the community. I also read about weaving in Laos, which was very much about the relationship between mothers and daughters: little young girls would learn weaving from their mum at a very young age.

When I finished that amazing workshop, I wanted to use these silk threads and bring that narrative into the gate through little tassels. At the same time, I had invited my mum to visit me, and I related to her the stories I had learnt about the Laotian mothers and daughters working together. There isn’t friction in the relationship with my mother, but there has been tension since I was a child.

Anyway, I invited her to come, and she was restless, so I introduced her to these silks, and she loved the idea of doing something with her hands. I taught her how to make these natural dyed silk tassels. We made them together. It felt like I’d crossed another border, another gate, of getting to know my mother in a different, more personal aspect. It was initially meant to keep her occupied, but then I thought, “This is so beautiful”. I decided to include them as part of the making of my gate. She had no idea what I was working towards. When I started constructing the tassels, then putting them together, she saw what I was trying to achieve and wanted to assist in the making.

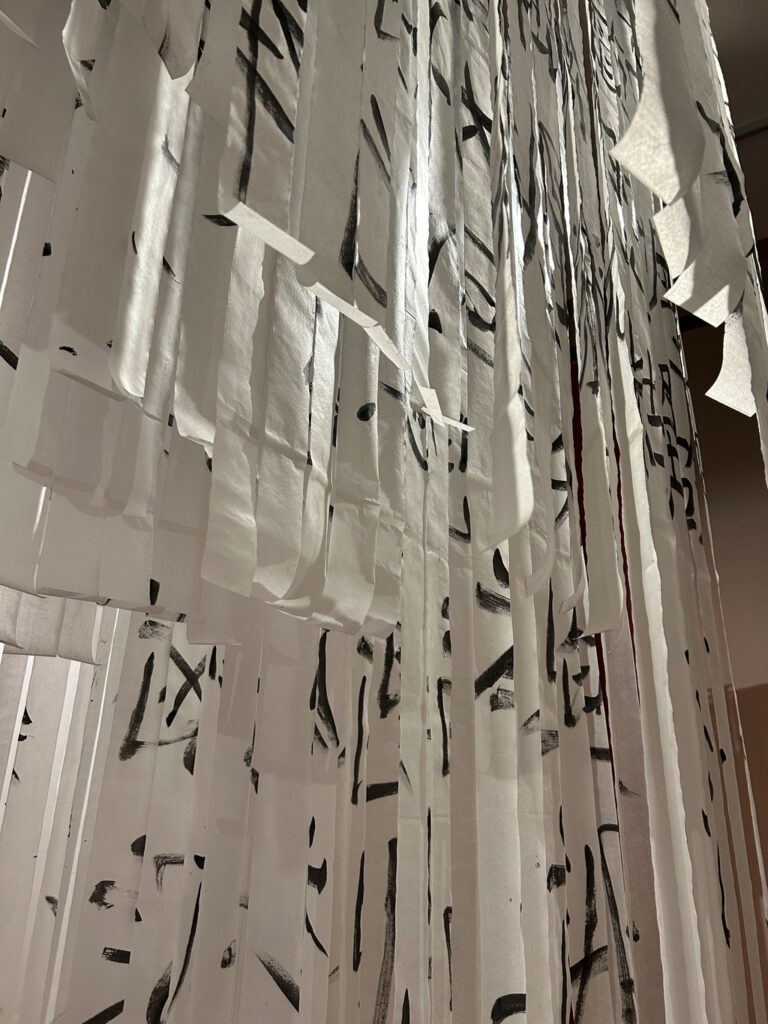

The next step was making long paper strips. There were 1110 strips altogether. The number is not significant, but I had a vision to realise a structure of a floating gate, and by the time I did the calculation, it was a beautiful round number. The Chinese characters written on it were a poem by Li Bai, about the moon. It’s a poem I grew up with that I could recite so precisely with its intonation, but I didn’t know how to read or write it. My mum made me recite the poem as a child every day before I left for school. I’ve recited it all my life until now, and I decided the poem is a true reflection of my being and had to be incorporated into that gate.

Every time someone crosses that threshold or that gate, you think of home. Or every time I cross that gate, I think of home.

Tearing the paper

For this project, I learned how to do calligraphy from my mum. She did the writing, and I mimicked her. In her own words, she knew she could “draw blood out” by watching me do it, obviously dissatisfied with my handwriting and skills. But I practised that.

I told her in the end that I had this idea: I’m not going to use the whole sheet, so no one’s going to see the full characters, so you don’t have to be embarrassed. I’m going to tear it. She was horrified by the fact that after it had been practised and written into a script, I would tear it. I said to her, “That was because you know how you said I’m Chinese, but I’m not Chinese enough? I know I recite the poem, but I still don’t read or write it. That’s how I feel about not fitting in and constantly questioning my identity and traversing between my cultural space”. I feel like, “You know, this is written, but I’m stripping it as a whole. I’m Chinese, but if I were to strip it apart, some bits and pieces don’t quite match”. I think the poetry is there; that’s what I was trying to relate to her. There was a sadness in her eyes as she saw that I had those thoughts about what she said about me. I think perhaps she didn’t really realise how that had impacted me.

It was on Chinese Xuan paper. After I stripped it, and I connected and joined it because they only come in a certain size, then I waxed it. I really wanted to have that transparency of the paper coming through with the text from the back when the light comes up.

I had to put another layer of muslin fabric over the top to strengthen the fragility of the paper, then I incorporated an eyelet in the muslin fabric so that it could be looped around an acrylic rod with cable ties. I did the entire calculation with my Excel sheets for the width, length and depth. So, I’d know the approximate dimensions of the installation. There is a total of 23 layers altogether.

✿

Li Bai “Quiet Night Thought” (靜夜思 – Jìng Yè Sī)

床前明月光

疑是地上霜

举头望明月

低头思故乡

Before my bed, bright moonlight gleams,

I wonder if it’s frost on the ground.

Raising my head, I gaze at the bright moon,

Lowering my head, I think of home.

✿

The conversation also touches on other interpretations of “gates”. Jacky recounts learning about the “Common Gate” in Broome, a historical site where Aboriginal people were forced to stay out of town after dark. This gate, though no longer physically present, is only a surviving post that still exists to this day as a “memory of all this trauma”.

Paradoxically, the moon poem in Jacky’s gateway transcends those kinds of spatial divisions, pointing to a space where there can be a lot of movement or journeying without the normal types of policing or borders that occur on land, much like migrating birds or shared celestial stories. The moon, with its universal presence and the myriad stories connected to it across cultures, reminds people of specific natural cycles that still exist despite the focus on politics and contemporary affairs. Jacky sees “so much power and so much beauty in the celestial world,” urging a focus on the “big picture”.

About Jacky Cheng

Jacky Cheng was born in Malaysia of Chinese heritage. She received her Bachelor of Architecture (Honours 1) from the University of New South Wales, Sydney. She is an artist, a facilitator and an art educator based in Broome, Western Australia. Visit jackycheng.com.au, follow @jackychengart and like facebook.com/jackychengart

Jacky Cheng was born in Malaysia of Chinese heritage. She received her Bachelor of Architecture (Honours 1) from the University of New South Wales, Sydney. She is an artist, a facilitator and an art educator based in Broome, Western Australia. Visit jackycheng.com.au, follow @jackychengart and like facebook.com/jackychengart