- Nicole Polentas, The Mothers Lament (θρῆνος), 2017, Sterling silver, copper, emu egg, alabaster, poly-putty, epoxy, glass powder, paint, 540 x 135 x 70 mm, photo: Kate Mollison

- Poly Nikolopoulou, Viaggio, 2017, silver, thread, 490 x 55 x 14mm

- Vikki Kassioras, Sky, 2017, twisted cord, plaited cord, sterling silver, 16 lucky eye talismans

- Melanie Katsalidis, right angle pendant, 2017, 9ct yellow gold, emerald cut watermelon tourmaline, free form rose cut white diamond, pendant 25 x 44 x 3mm on 45 cm chain

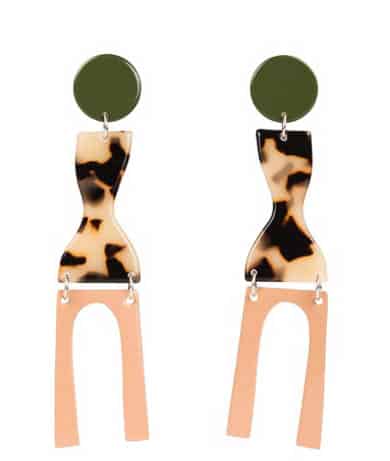

- Bianca Mavrick, Faro earrings, 2017, colour-coated stainless steel, sterling silver, blue quartz, Italian cellulose plastic, 100 x 25mm, photo: Lisa Brown

- Anastasia Kandaraki, Still I can stand, 2015, 14ct yellow gold, oxidized sterling silver, 55 x 40 x 22 mm

- Demitra Ryan-Thomloudis, Tilt up, 2017, cement, resin, foam board, paint, 160 x 163 x 26 mm

The relationship between the cultural heritage of an artist and their work is complex. It might be an obvious statement to make, but it was something that arose often as I viewed the work of several jewellery artists of Hellenic background, most of who live in the diaspora (including Australia) during Radiant Pavilion Melbourne Contemporary Jewellery and Object Biennial held in August to September this year. I set out wondering whether their work relates to their ethno-cultural backgrounds, and, if it does, the ways in which this is manifested. Beyond obvious symbols, perhaps materials and techniques, I was not entirely sure what a Hellenic influence might encompass.

Melbourne-based Vikki Kassioras tells me “her Greek heritage absolutely” influences her,” though, she “couldn’t tell me which part.” “Lucky eyes” is what she called the eye object talismans incorporated into her neck piece Sky, displayed at the group exhibition Talismans for Travel. While this symbol seems to be a (slight) variation of the Greek “evil eye” amulet, it was one that was very familiar to me, having Greek heritage myself. Generally, Kassioras’s symbology is directly inspired by classical Greek mythology and other parts of the ancient world (including Mesopotamia, Egypt, Rome). “The whole region is rich in inspiration” for her.

Like Kassioras, Melanie Katsalidis, also Melbourne-based, has an interest in the ancient world. She is “fascinated by the structures left by the ancients” and influenced by geometry and certain styles of architecture, both of which she was exposed to via her architect father and during trips to Italy, her mother’s country of origin. In her exhibition NEO Cuts, Katsalidis’s rings, earrings and neck pieces exhibited both sets of influence. Gems sourced in Australia (eg Queensland sapphires) and overseas (eg watermelon tourmaline from Brazil) were incorporated into strong geometric, primarily gold forms. One of the reasons Katsalidis is so interested in ancient structures is the fact that they have endured for so long, something she hopes her jewellery will also do.

Athens-based Anastasia Kandaraki lives side by side with the kinds of structures Katsalidis refers to and is clearly influenced by them. She says (via email) that “ever since I remember myself I see around remains of past times. Abandoned, crumbling buildings falling apart; the marks of time on them; yet, alive.” Still I can stand, a piece in her series Living Ruins shown as part of the group exhibition Time:Frame at Tinning Street Presents, combines a sense of the “ruin” and the geometry that enables it to “stand”. Made of oxidized sterling silver and fourteen karat gold, (the individual metals, as well as the combination, are features of a lot of art jewellery made in Greece) and using the traditional technique of lost-wax casting (like a lot of Kandaraki’s work), it “revolves around deconstruction and reconstruction. By going back to the roots, I destroy and rebuild in an attempt to discover my cultural identity and express human values,” she comments (via email).

Like Katsalidis and Kandaraki, Demitra Ryan-Thomloudis, based in the USA, is also drawn to “the built environment” [via email], though her interest lies more in “the organisational components of architectural construction.” Her robust-looking pieces, also shown as part of Time:Form, resemble miniature parts one might find on a building site. The object Tilt up consisted of two parts that reminded me of small-scale architectural models. As with a number of pieces in this series, it is made partly of materials not traditionally used in jewellery-making (cement, foam board). Ryan-Thomloudis views the Hellenic influence in her work in terms of her “exposure to Greece’s deep history in the decorative arts” heightening her “sensitivity to material, form and craftsmanship in my own practice” (via email).

Geometric forms, as well as a colour palette inspired by the hot lush Queensland surrounds in which she resides, are central features of Bianca Mavrick’s work. The pieces, of simple, bold lines, and consisting of precious stones and metals (eg. sterling silver, blue quartz), found objects and fabricated materials, displayed during her exhibition Memory + Assembly, were inspired by her experience growing up in a Greek-Italian family in sub-tropical Queensland, one of the few artists I interviewed whose work is drawn directly from their migrant experience. Her Faro earrings, composed of colour-coated stainless steel, sterling silver, blue quartz and Italian cellulose plastic bring to mind early Cycladic figures, (perhaps equine), albeit more colourful than the original. Mavrick’s “motifs and symbology…are things derived from my Greek heritage,” she says.

Another artist influenced directly by her Hellenic heritage, particularly her Cretan heritage, is Melbourne-based Nicole Polentas. The Mothers Lament (Θρηνος) displayed as part of her exhibition Reflector Receptor: Narratives of Experience, and composed of sterling silver, copper, alabaster, poly-putty, epoxy, glass powder and paint, had a miniature neo-classical looking woman’s bust at the centre of an emu eggshell. While she seemed to have “hatched” from that, the marine foliage decorating her cleavage seemed to suggest that, at the same time, she had emerged from the sea, perhaps implying two places of origin. Hanging from either side of the bottom of the egg shell are two curls of Greek words, possibly laments, a very old Greek tradition, which Polentas feels “for a long time, were the only way women could express themselves.” This “personal narrative”, as Polentas describes the exhibition, forms a “dialogue which is grounded in the artist’s personal experiences.”

Similarly, Poly Nikolopoulou, who lives in Greece, sees her jewellery as a means of communicating her inner world. The series viaggio, also part of Time:Form, came about, she says (via email), from a personal need to express something. The pendant Viaggio, made of silver and thread, looks like a slightly worn little suitcase, referring directly to the series title—a symbol, perhaps, of literal and figurative journeys, “a suitcase of life”, as Nikolopoulou writes in her artistic statement.

As with the work of Polentas and Nikolopoulou, jewellery is a means of communication for New Zealand-based Stella Chrysostomou, as she endeavours “to converse in objects,” she says (via mail). Her Utter Necklace in the group exhibition Utter, held at Melbourne’s Paperback Bookstore, incorporated fragments from a book page which the viewer tried to read and comprehend, but which was not really possible, perhaps referring to the nature of conversation. While she says (via email) that her “Greek heritage doesn’t seem to play a direct influence in my work,” she later comments that “maybe the influence is covert rather than overt.”

Influences “covert” and “overt” seemed to characterise the relationship between the work of the artists I interviewed and their Hellenic heritage. The expression of those influences was diverse and unique to each artist. While this may also have been an obvious assumption to make, exploring those multifaceted manifestations was an enriching process.

Author

Vicky Tsaconas lives in Melbourne, writes poetry, essays and reviews and has worked in arts management and social policy. She has worked in partnership with visual artists and film-makers on independent cross art-projects. Currently, she is working towards the completion of a manuscript, facilitating a poets’ group and collaborating on a number of film projects.

Vicky Tsaconas lives in Melbourne, writes poetry, essays and reviews and has worked in arts management and social policy. She has worked in partnership with visual artists and film-makers on independent cross art-projects. Currently, she is working towards the completion of a manuscript, facilitating a poets’ group and collaborating on a number of film projects.