Mary Louise Buley-Meissner and Vincent Her pay homage to the embroidered stories of Hmong artist Xao Yang Lee.

Today, Hmong Americans number around 300,000. They reside across the United States from Massachusetts to California and from Alaska to Florida. Starting in 1975, they arrived as refugees of the Vietnam War, allowed into the US because Hmong men had been recruited by the CIA to fight a Secret War (1959 to 1975) in Laos against Communist forces. During that conflict, more than 17,000 Hmong soldiers and more than 40,000 Hmong civilians lost their lives. After the Vietnam War, thousands of Hmong emigrated to Europe, North and South America, and Australia.

For more than three generations, Hmong Americans have called the US their home and homeland. Like other immigrant groups, they give voice to their histories and hopes in many ways. Here we focus on one artist, Xao Yang Lee, who is using story cloth to safeguard, share and interpret Hmong history stitch by stitch.

Origin of story cloth

Women in refugee camps first began to make story cloths in the 1970s because they wanted to remember and pass down what they had learned growing up in Laos and what they had witnessed during the war. However, what an individual artist chooses to highlight depends on her perspective regarding what is true to the history of Hmong people. More importantly, her creativity expresses a commitment to art shared by Hmong women in forms that are emotionally driven, collectively meaningful, and historically irreplaceable as representations of a reality that otherwise could remain hidden. Our aim is to broaden and deepen our readers’ understanding of the interrelationship of identity, history and culture as we look closely at one story cloth with exceptional insight into Hmong lives.

The artist

Xao Yang Lee is a story cloth artist known to us through family connections. Her skills in sewing have developed over sixty years of practice as a child in Laos, a mother in Thailand and a grandmother in the US. The story cloth featured here measures eight feet wide and over five feet high, showing the intricacy and complexity of this art form,

Xao Yang Lee openly shared her life history with us as we discussed her story cloth. During the Secret War, she lost her first husband and led their five children to a refugee camp in Thailand. She settled in Sheboygan, Wisconsin in 1980, but now lives with her second husband in Milwaukee, where they operate a transportation business with a son.

In the early 1980s, to supplement family income, Mrs Lee began to market her sewing at weekend art and craft fairs across Wisconsin, while never missing a day of work on an assembly line for a sock company. As she entered and won art competitions, her sewing became known for making Hmong art appealing and Hmong history intriguing to a broad, multicultural audience. In the past ten years, she has been recognized as one of the most skillful story cloth artists in the Midwest. Yet she remains humble about her accomplishments, which include an exhibition of her sewing at museums such as the Kohler Arts Center.

Moreover, through her sewing, Mrs Lee has become keenly aware of her identity as a Hmong American. Most importantly, she hopes that her children and grandchildren will “remember who they are whenever they look at my story cloth. I want them to remember where they came from. I want them to look deep inside themselves—and remember Hmong people through my work.”

Reading a story cloth

We have chosen to highlight three features of Xao Yang Lee’s story cloth narrative, revealing how history can be retold by stitches on the fabric of memory: 1) Hmong moving forward through time and place; 2) emptiness revealing as much as explicitness, and 3) empathy emerging through shared humanity.

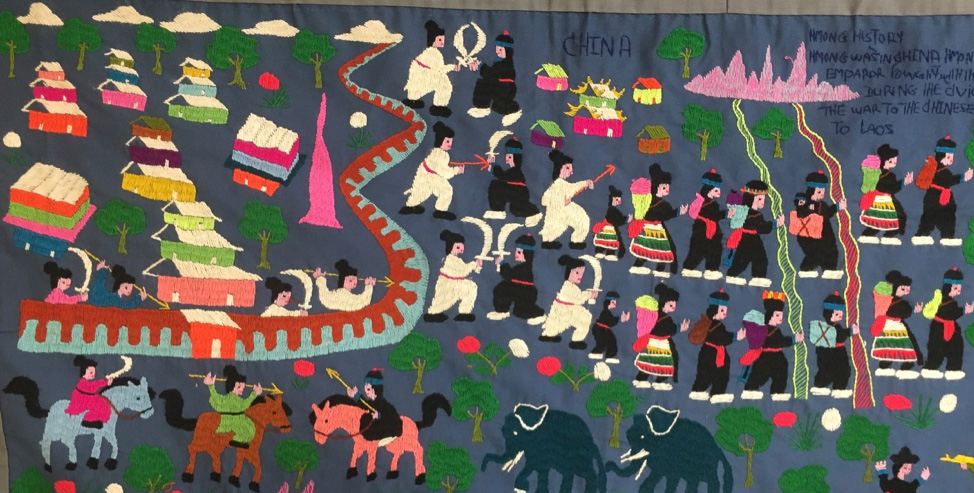

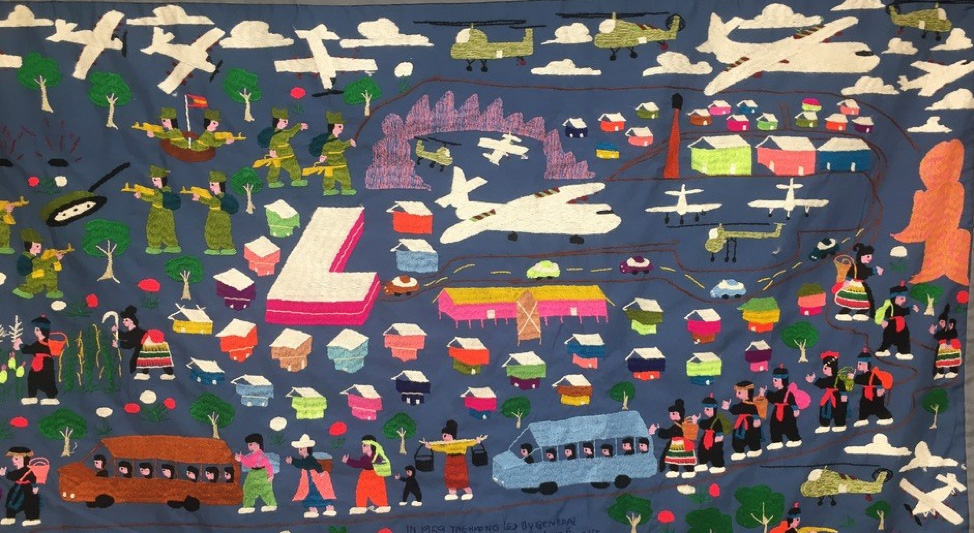

Most striking to us is how Hmong people in this narrative keep moving forward, not only as they are pursued by their enemies, but also as they find their own way to survive another day of war. The chronology of events winding down the fabric takes viewers through conflicts with Chinese rulers, French colonists, Japanese invaders, Vietnamese “liberators” and Laotian collaborators. During the Secret War, more than 150,000 Hmong people became refugees in their own country after their homes and villages were destroyed.

As depicted in Mrs. Lee’s story cloth, they never stop moving, carrying only what they need to survive in the jungle—a basket of rice, a cooking pot—and they never walk alone. Hmong refugees turn back only when they see death waiting for them, as they do when they reach a bridge where soldiers are massacring civilians (as seen in the center of the cloth leading to the river). Then they regroup and move on.

Secondly, Mrs. Lee’s interpretation of Hmong history comes across clearly in what she leaves out as much as what she decides to include. Most notably to us, the Mekong River stretches across the story cloth (from the top left corner to the bottom right corner), demarcating the death above from the life below. Crossing the Mekong River was the only way to reach Thai refugee camps, but few Hmong people could swim. Intensifying the danger were soldiers stationed on the riverbank and sent out on the river to shoot those trying to cross, whether men, women or children. Thousands of people lost their lives here.

Yet Mrs Lee gives us a view of a river eerily empty of such carnage. Rafts, bamboo baskets and inner tubes float by as if we are distantly watching everyone meeting their fate. Most disturbing are the empty rafts, which would have held people who have been shot or who have drowned. What we do not see is what we are forced to imagine for ourselves, perhaps so that we will put ourselves on that river at that terrible time.

Thirdly, we appreciate how Mrs Lee encourages viewers to empathize with Hmong people by details which reveal shared humanity. The hands of Hmong people, for example, often are shown in supplication during their escape as they seek mercy, food and shelter, directions and safe passage.

People who cross the Mekong to Thailand cannot stop moving until they reach refugee camps, where they must prove that they were on the right side of the war, that is, the American side. Their hands reach out (along the bottom edge of the cloth) to border guards, NGO staff and American personnel who have the power to help them or turn them away. Every step of the way, they are reaching out for a new life, a future in a new country, the possibility of Hmong people finding peace after centuries of conflict. As Mrs Lee encourages us to see, their hands are those of refugees worldwide, who now number in the millions.

The whole story

The only way to understand any part of the Hmong story is to learn the whole story, yet the whole story is always in the process of being composed. In our reading of their work, Mrs Lee and other Hmong story cloth artists create histories, narratives, protests and laments. They create memories: sewing a landscape and touching again the land they once called home, weaving their own blood, tears, and hopes into a fabric strong enough to withstand whatever changes the future may bring. We hope their work continues to make Hmong history visible and thought-provoking to a worldwide audience.

Further Reading

Caitlin, Amy. “Textiles as Texts: Arts of Hmong Women from Laos.” Textiles as Text: Arts of Hmong Women from Laos. Los Angeles: The Woman’s Building, 1987. n.p.

Conquergood, Dwight. “Fabricating Culture.” Performance, Culture and Identity. Ed. Elizabeth C. Fine and Jean Haskell Speer. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1992. 207-248.

Craig, Geraldine. “Patterns of Change: Transitions in Hmong Textile Language.” Hmong Studies Journal 11 (2010): 5–6.

Cubbs, Joanne. “Hmong Art: Tradition and Change.” Hmong Art: Tradition and Change. Sheboygan, WI: John Michael Kohler Arts Center, 1986. 21–29.

Dewhurst, C. Kurt, and Marsha MacDowell, eds. Michigan Hmong Arts: Textiles in Transition Lansing: The Museum, Michigan State University, 1984.

Garrett, W. E. “The Hmong of Laos: No Place to Run.” National Geographic 145 (January 1974): 78- 111.

Gerdner, Linda. Hmong Story Cloths: Preserving Historical & Cultural Treasures. Atglen, PA: Schiffer, 2015.

Hamilton-Merritt, Jane. Tragic Mountains: The Hmong, the Americans, and the Secret Wars for Laos, 1942–1992. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Hickner-Johnson, Corey. “Taking Care in the Digital Realm: Hmong Story Cloths and the Poverty of Interpretation on Hmongembroidery.org.” Journal of International Women’s Studies 17.4 (2016): 31-48.

Hillmer, Paul. A People’s History of the Hmong. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2015.

Lee, Gary Yia, and Nicholas Tapp. Culture and Customs of the Hmong. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2010.

McCall, Ava L. “Speaking through Cloth: Teaching Hmong History and Culture through Textile Art.” The Social Studies 90.5 (1999): 230-236.

McDowell, Marsha. Stories in Thread: Hmong Pictorial Embroidery. Lansing: University Publications, Michigan State University, 1989.

Petersen, Sally. “Translating Experience and the Reading of Story Cloth.” Journal of American Folklore 101.399 (Jan.- March 1988): 6–22.

Umberger, Leslie. “Xao Yang Lee: A World Away.” American Story. Sheboygan, WI: John Kohler Arts Center, 2009.

Authors

Mary Louise Buley-Meissner, Professor of English at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, has taught multicultural literature in China, Hong Kong, Japan and Germany as well as the US. She especially enjoys introducing Hmong American literature and life stories to first-generation students who are exploring their own cultural heritage.

Vincent Her, Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, teaches courses in Anthropology and Hmong American Studies. He lives in Southeastern Wisconsin with his wife and three daughters.