- Debbie Adamson, Coal Stump, 2016, rubber, 150x150x10mm, Peieo Arico

- Jane Dodd_Horse Tail, 2016, cow bone, sterling silver, 120x35x15, Peiro Arico

- Jane Dodd, Rat Tail & Dog Tail, 2014, 2016, ebony, cow bone, sterling silver, 90x 10, 90×15, Piero Arico

- Jasmine Te Hira, The Beauty of Invisible Grief, still from video, 2016

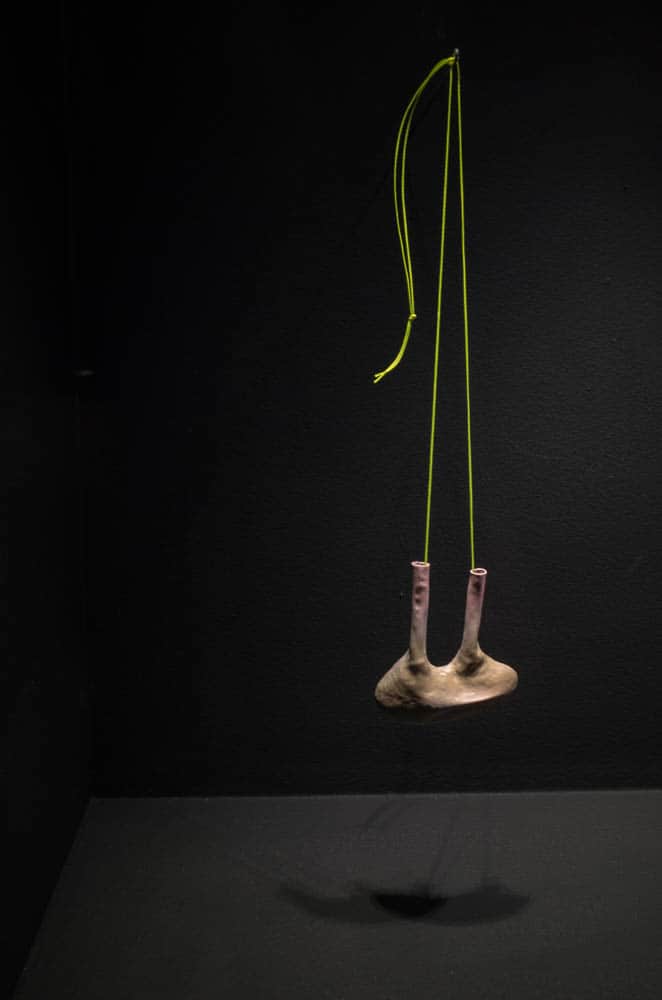

- Raewyn Walsh, Hrmph copper paint, 85×65, Piero Arico

- Vanessa Arthur_Paint, erase, repeat, 2017, copper, brass silver paint, 20mm x 160mm, photo Piero Arico

- Sione Monu, Canberra Family Portraits, 2015, photograph, 100×150, photo: Piero Arico

- Woulfe, Silvergraft, 2010, Female Ritual II

“I like reality. It doesn’t terrify me” – Marti Friedlander

An invitation

In January 2017, I was invited to participate in a multi pronged curatorial exhibit (Exposé) in which six curatorial teams were invited to share and populate Espace Solidor (Cagnes-sur-Mer, France). The show was conceived and organised by, writer and contemporary jeweller, Benjamin Lignel who asked each curator to design a project that would serve as a precursor to some larger, future show.

Being based in Aotearoa, NZ, I set out to explore the idea that there is something unidentifiable bubbling under the surface—something all at once mysterious and ugly and dark and beautiful. The idea was to tap into the current generation of Pacific-based makers, who are both following and updating the ground-breaking work of the bone, stone, shell jewellers. Someone once told me that Pacific themes and culture were impacting all forms of Pacific art, regardless of the cultural heritage of the maker. I wanted to see if this was true and if so how a series of disparate works would interact and speak to one another when brought together.

A guided tour

If we were standing together on the square of Cagnes-sur-Mer in the French Riviera under the shadow of a medieval castle, you would remark on the brilliant blues of the distant Mediterranean in contrast with the chalky yellow walls of the mountaintop village. We would cross the plaza and enter the Espace Solidor. It would take our eyes a moment to adjust to the theatrically dark rooms.

The dramatic lighting would be accompanied by the soft intervals of singing of a Māori waiata (song). You might tell me the sound of the voice is lulling, inviting. The contrast between the lighting and soundtrack would transport us to a faraway place of unknown origin.

Scanning the room horizontally, you would see a combination of physical jewellery, brooches, pendants, earrings, large, softly lit photographs hung in a vertical stack, a small bright cluster of family in Pacific leis and a very still video.

We might discuss how each work is underpinned with unease, but resolved with a lightness of touch. Lightness, like the virtue discussed in Calvino’s Six Memos for The Next Millennium, or the lightness that comes as the natural result of the dark night according to creation myths of te ao Māori (the Māori world).

Jasmine Te Hira masters this lightness in her video The Beauty of Invisible Grief. Te Hira’s whakapapa (genealogy) connects her to the Māori iwis (tribes) Te Rarawa and Nga Puhi, the Cook Islands and England.

We could get lost in a conversation about the effects colonisation has had on many families (and generations) of Māori descent, who experienced a break with not only their customs and land, but also their language. From around 1860s to middle of twentieth century, there was formal and informal suppression of the Māori in schools to promote assimilation into the wider (English) community. Te Hira’s response in her search for identity and mother tongue was this video in which she wore an ice tiki, made from the waters of her home awa (river). This subtle film focuses on the sitter’s lips, chin and chest as the icy pendant melts, burning an imprint onto her skin. Every ten minutes the waiata (song), te pou is heard. Te pou, can be translated as a territorial symbol which underlines the importance of the water in this work and completes the cycle.

You would probably walk right up to Selina Woulfe’s lush, dim Silvergraft photographs to examine them in detail. Up close you can see the surgical steel is pierced through the nude flesh as well as the delicate Silvergraft. You notice the photographs document “an invasive procedure performed on the body”. I’d tell you that Wolfe sees them as a kind of protective, decorative layer. Being pierced is a private ritual. We might wonder together about this connection of pain, beauty, and the young Pacific body.

Next, we might talk about the makers of European descent and how interested I am in seeing the way the richness of the Pacific infiltrates all that live there. Debbie Adamson’s practice is strongly connected to the rural landscape of the South Island and the impacts intensive farming is having on the landscape. Continuing her exploration with man-made material, the large-scale, rubber breastplates loom massive and mysterious. When nestled amongst strong Pacific images, the conversion changes radically and connects to historic Pacific adornment.

Incredibly, Vanessa Arthur’s large platter was almost identical in size to Debbie’s pendants. A small coincidence that caused me to reword the whole layout of the show. The quirky beauty of bad wall graffiti “tidy-ups” inspires Vanessa silverware. I am excited by her interest in decay in an urban landscape, and the dangerous territory that leads to on these shaky isles.

I might remind you that Māori was an oral language. You might correct me, and add that it was not only oral, but weaving and carving were widely acknowledged as carriers of information. We might agree that Māori is an object-based language. And would understand that carvers in te ao Māori were a big deal. Jane Dodd, an artist whose work straddles multiple generations of New Zealand jewellery movements, is not a man, nor of Māori descent, but she is making formidable carvings (whakahiro—carving— is traditionally the role of men in Māori culture). Her current work (Rococo Revolution) is based on animal tails. She is an enigma in NZ, mixing traditional material (bone) and techniques (carving) while creating work that fits snugly among her contemporaries on the modern jewellery scene.

I would steer you to another hero of the unease, Raewyn Walsh. She is interested in using metal and copper, utilising techniques and unexpected colour combinations to tiptoe between repulsion and obsession. The series Weird Friends is full of flesh tones, goose bumps, awkward forms and lightness. I am again reminded of Calvino,

“Soon I became aware that between the facts of life that should have been my raw material and the quick light touch I wanted for my writing, there was a gulf that cost me increasing effort to cross. Maybe I was only then becoming aware of the weight, the inertia, the opacity of the world-qualities that stick to writing from the start, unless one finds some way of evading them.”

We might end in front of Sione Monu’s delightful Canberra Family Portraits. The works (in the form of leis) were made each day from material selected from the garden for a specific family member. Once the lei was finished, the recipient was coerced into sitting for a portrait and the photo posted to social media. The quiet beauty of this gesture and its fleeting nature, translated perfectly, even across oceans. Sione Monu’s family portraits, are arranged as if the group were quietly standing for a picture.

Gathered together, this odd family of objects reveal a richness and an evolving conversation about a little culture. It is a quiet, but the work has an evocative energy and glimmer. It was a privilege to pick out these works and give you a tour.

Further reading

Because the project contained a number of videos, a website was created to capture and share the work – Expose documentation.

Artists:

For a larger history of issues affecting Maori Language see here.

Author

Kristin D’Agostino is contemporary jeweller who transforms found objects using traditional craft techniques. Her curatorial initiatives include: Broach of the Month Club, the Jewellers Guild of Greater Sandringham, and the Overview newsletter. She is on the board of Objectspace and is the Art Jewellery Forum ambassador for New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand is her home.

Kristin D’Agostino is contemporary jeweller who transforms found objects using traditional craft techniques. Her curatorial initiatives include: Broach of the Month Club, the Jewellers Guild of Greater Sandringham, and the Overview newsletter. She is on the board of Objectspace and is the Art Jewellery Forum ambassador for New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand is her home.