- Commuting in the village by tricycle. I took a selfie with Ms Rantilah.

- A batik producer family in Bangkalan, Madura Island.

Puspita Ayu Permatasari shares her journey to Madura island, whose batik inspired her to develop an app that uses artificial intelligence to decode its patterns.

Batik isn’t just a type of textile. For me batik is personal. Just like a human, its patterns provide a DNA that codifies a history. My passion for batik has been passed down from my grandmother and my mom. My grandmother was the descendant of Sumenep royal family, just passed away in May 2020. In each social occasion, she always wore a jarik, a Javanese word for a long piece of batik textile wrapped around the body with pleats in front of the waist. She put it meticulously around her body with such emotion on her face. When I was eight years old, I heard her say, “Batik is a sacred textile”.

Gajah Mungkur symbolizes an elephant (“gajah”) that is trapped (“mungkur”) in the bamboo forest. It symbolises a huge longing for a person trapped in the heart and cannot be expressed.

Long after she implanted the sacred idea of this textile, my interest was growing in particular in learning symbols, any kinds of symbols. I wasn’t thinking about studying batik in particular, but I was interested in learning the Mandarin language, a language with millions of meanings behind symbolical Kanji (汉字).

In 2010, I graduated with a Bachelor of Chinese studies, University of Indonesia. Then, I was working as an interpreter for Mandarin/English in Indonesia. In 2014, after visiting batik villages during one week getaway in Madura Island, I took an interest in the batik industry from a tourism perspective. Later on, I decided to continue my study. With the help of my best friend Rila Hilma, I applied for a master degree in the Management of World Heritage Sites and Tourism in Université de Paris 1 Panthéon – Sorbonne, France. It wasn’t easy to apply for this master program. It requires a high level of French language competencies. It was my research plan to develop sustainable cultural tourism in the batik villages of Madura that sparked the interest of the Dean to accept me.

During my master study period, I managed to join an internship in the Delegate of Indonesia for UNESCO. I had to learn the requirement of UNESCO in maintaining the status of world Tangible/Intangible Cultural Heritage. To complement my findings, in February 2016, I conducted a research field trip in four cities of Madura Island: Bangkalan, Sampang, Pamekasan, and Sumenep royal city.

Madura people are very conservative, religious, and strongly uphold their batik culture. These distinguishing characteristics contribute to the preservation of batik in many areas, even at the family level. I learned different nuances of batik production, colour schemes, and the meanings of batik motif in each city.

When I stopped by in Bangkalan city, I encountered Ms Rantilah, a senior producer of the village. I stayed with her for three nights, listening to her stories and learning how she managed her batik production activities. Her house is located not far away from the market where she goes to sell her batik textiles.

At first, I was afraid that Ms Rantilah would feel uneasy with me. Would she be open up to me as I am an outsider—a person coming from a city—a stranger in the village? I felt happy when she invited me to visit her relatives and best friend, observing them closely producing batik. She also took me to some family and friends who work in the batik industry. One of her relatives lives in the 200 square metre house that has five rooms and a big yard which is used for drying the batik. The local people called this traditional house of Madura, tanean lajeng.

There are seven people in the family, including in-laws and grandchildren, who live here altogether, working in the family-run-batik business. As they invited me to discover the place, I was surprised that I hardly found any furniture and household appliances in the house. The rooms are mostly reserved for batik textiles in each stage of processing: pre-processed white cloth, half-processed batik textile, coloured batik textile, and the finished products.

I was thinking that this house and this family might represent the cultural landscape of the batik industry elsewhere. On another occasion, Ms Rantilah also invited me to visit her friend, Ms Yuli, who produces Batik Genthongan, the rarest and the most exclusive type of batik textiles from Madura. Different from the one where all the family work in the same family business, Ms Yuli works alone. Her son has no interest in continuing this work, so she wanted us to encourage the young generation to learn the knowledge behind the batik heritage.

After ten days of my 2016 research journey in Madura, I realised that I could not make an impact on the preservation of batik in Indonesia unless I create a platform to raise the awareness of batik. I started my PhD with the mission of creating digital technology whose aims are to better communicate the exceptional socio-cultural values of batik in tourism and fashion contexts through new forms of digital media.

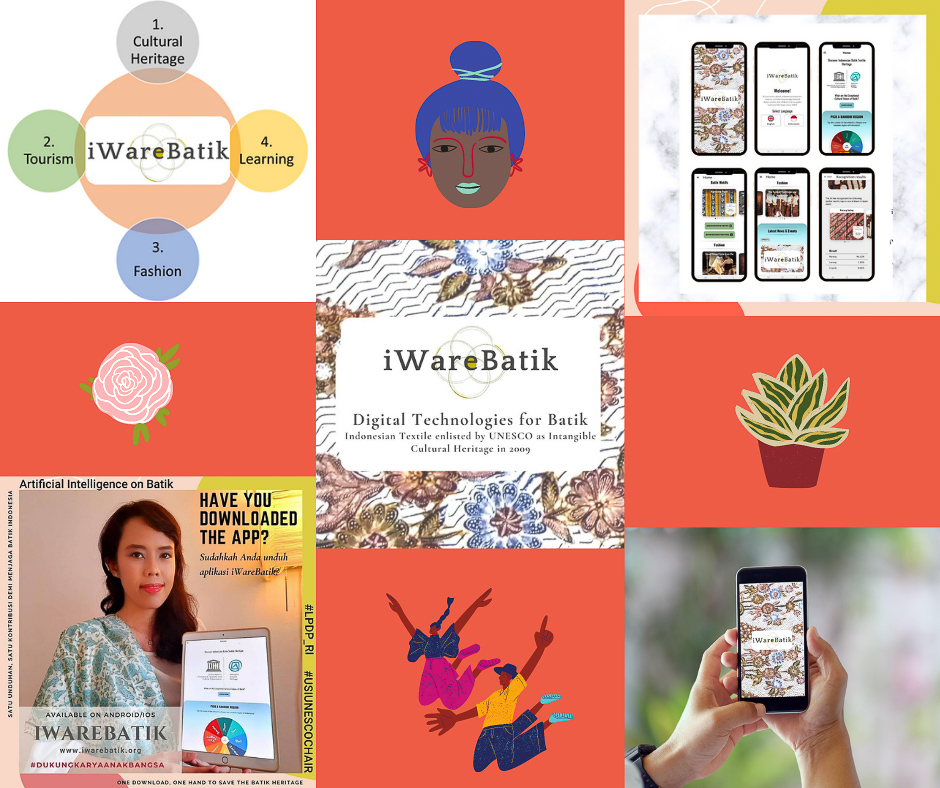

- the iWareBatik application features and functionalities, available on Android and iOs. More info: www.iwarebatik.org

The iWareBatik website and mobile application were born in 2019. It stands for “interactive software of batik”. It can also be interpreted as “I am aware of batik” or “I wear batik”. iWareBatik aims at reigniting people’s passion for learning and understanding the Indonesian Batik tradition, as intangible cultural heritage.

In the past three years, I have managed a team to decode 124 Batik motifs and their meanings with artificial intelligence digital technology. This incredible research journey was prompted by my curiosity to discover how the advancement of Information communication technology could support the preservation of Indonesian Batik UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage since 2009.

The bilingual platform takes the users to the map of Indonesian cultural diversity, linking them to the wonder of batik identity in each province and its destinations. The app itself, available in English and Indonesian language, can be accessed through the Android and iOs platforms. It features a spinning wheel that prompts the user to open one region. One doesn’t need 124 days to memorize the meanings of 124 batik motifs and to discover the 129 regional scenic destinations across 34 provinces. They are all being summarized in a one-minute visual journey of each province inside the app.

As one of the architects of this project, I would like to say that this is presented in order to promote digital technology for humanity. From Indonesia to the world, entrusted to the hands of UNESCO Chair USI, promoting the peace and wise use of digital technology for preserving of what so-called intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

It has been a wonderful three years together with the ELab Usi team and Indonesian iWareBatik team consisting of eight wonderful people with different expertise, including Reinard Lazuardi Kuwandy, a student originally from Bandung who built the artificial intelligence to recognize eight different motifs (Parang, Kawung, Lereng, Mega Mendung, Ceplok, Ampiek, Merak, Gurdo), with the help of his family compiling 800 motif images for machine learning.

Only by the grace of God that leads us to complete this project. I acknowledge the great patience and guidance given by Professor Lorenzo Cantoni for the completion of the iWareBatik.

When you try the camera feature inside the app, will you find the magic of AI technology to reveal the hidden past of a batik motif?

“One Download, One Hand to Save the Batik Heritage”

While we know that we have travel limitations, bear in mind that you have the freedom to wander inside the wisdom carried by the thousand-years old journey of Indonesian Batik. iWareBatik is not just an app. It carries you to the wisdom of humanity, far beyond the time one knows a technology.

Author

Puspita Ayu Permatasari is a PhD Candidate and Research Coordinator of iWareBatik Information and Communication Technology (ICT) for Intangible Cultural Heritage and Tourism at USI UNESCO Chair Università della Svizzera italiana, Lugano, Switzerland. Puspita is of Indonesian origin. Her PhD research focuses on how to orchestrate digital media to communicate the UNESCO intangible heritage of Indonesian batik textiles with global fashion and tourism audiences.