Zoe Porter and Aiko Ohno, Before and After the Dive I, 2021, Digital print on Hahnemuhle paper, ink, watercolour, pencil, embroidery thread, 19.5 x 30cm

Zoe Devenport writes about an exhibition by Aiko Ohno and Zoe Porter that celebrates the life of female divers in ink and thread

Katsugi (Dive), by artists Aiko Ohno and Zoe Porter, plunges into Japanese ama freedivers’ lived realities and revels in transmuting visions of a thousand-year-old cultural tradition into a surreal, anthropomorphised Atlantis. Through the melding of the artists’ collaborative mediums, the exhibition meditates on the ancient connection of ama to their ecology and celebrates a female agency that sets aside the ama’s sexualised portrayal in Japan’s art history.

Ama (海女, “sea women”) are female divers trained to hunt for a wide marine bounty without modern scuba gear. The ama harvest delicacies like abalone, octopus, and kelp with only the air in their lungs and freediving techniques perfected by generations. While ama as an occupation has been an entrepreneurial institution for women to support themselves in male-dominated society, ama as cultural capital were popular erotic figures depicted in ukiyo-e (浮世絵, “floating world”) prints and paintings throughout Japanese art history.

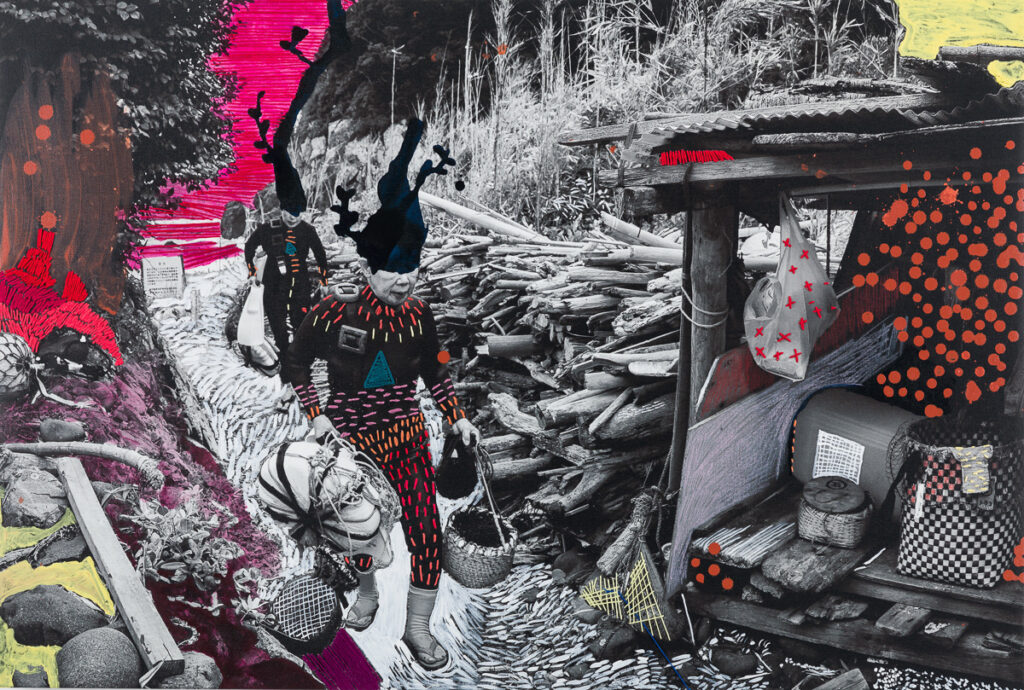

- Zoe Porter and Aiko Ohno, Before and After the Dive IIII, 2021, Digital print on Hahnemuhle paper, ink, watercolour, pencil, embroidery thread, 19.5 x 30cm

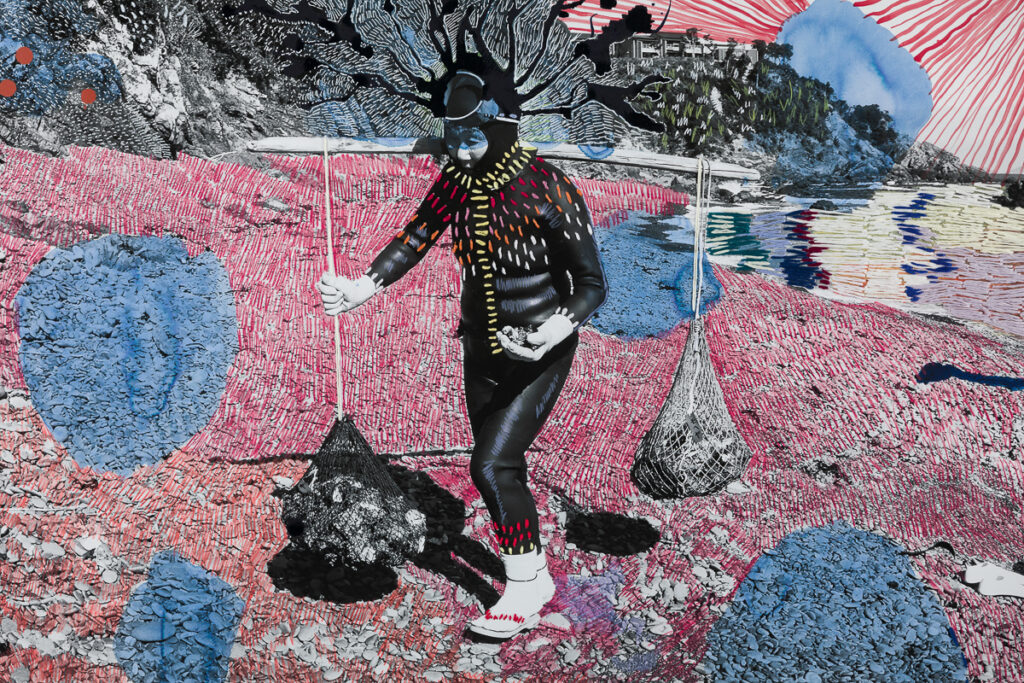

- Zoe Porter & Aiko Ohno Ohno & Porter, Ijika Ama with Awabi Catch 2021 (detail) Digital print on Hahnemuhle paper, ink, watercolour, pencil, embroidery thread. Image – 70.5cm x 100cm. Framed UV70 glass – 93cm x 126cm.

- Zoe Porter & Aiko Ohno Ohno & Porter, Ijika Ama 2021 Digital print on Hahnemuhle canvas, ink, watercolour, acrylic paint, pencil, embroidery thread unframed 70.5cm x 100cm

Kitagawa Utamaro, an Edo period luminary, was one ukiyo-e artist who featured beautiful young ama in a number of his adult books of print polyptychs. Per traditional Japanese ease with nudity, ama originally dove naked with a belt of tools and nets before adopting modern wetsuits. This unintentionally inspired much explicit and risqué work from Japanese and international artists. Katsugi (Dive) is in part a rebuttal to the cultural association of ama with sexually explicit art largely created to sate a lecherous male gaze. Porter and Ohno bring the cultural tradition of the ama to Australian audiences removed from this sexualisation, instead empowered by their relationships with their ecology and each other.

The exhibition sits neatly in Onespace Gallery, framed by specially commissioned mural installations by Porter that extend the marine tableau across walls and twist tentacles up beams. To the immediate left are the most collaborative works of the show, prints of Ohno’s photos that have been painted, marked, and stitched by Porter. The artists’ individual work leads to an installation of Ohno’s own wetsuit, as well as one made in felt by Porter, stitched and suspended under a fishing net at the rear of the space. Ohno’s framed photos show her diving into kelp forests and tangling with an octopus, alone underwater in a blue-toned world at once lonely and brimming with life. Porter’s glowing watercolours, variously sized unframed vignettes and art books, feature the ama in fantastical scenes of work and rest.

- Zoe Porter, Urchin Barren, 2021, watercolour and ink on arches, 56 x 77cm.jpg

- Zoe Porter & Aiko Ohno Cephalopod Dream 2021 Watercolour & ink on arches 56cm x 77cm

The wildness of the ocean is apparent in every work, the pull of its tides shifting the very forms of the women who dive into its depths. Fins, scales, tentacles or kelp grow across and beyond their skin as they swim down to the seabed or feast on their spoils by the shore. This ecomimesis, borne in the collaboration between Ohno and Porter, reforms the ama as hominid hydro-adaptations, grown less human and more yōkai (妖怪, “phantom”) creatures of Japanese legend. Yet why should humanity be defined by its separation from nature? Emerging onto shore with seaweed blooming from their heads, ama seem to have devoted themselves to an otherworldly sea in a surreal visualisation of Shinto ecological beliefs.

Shinto is an indigenous Japanese belief system known for its reverence of nature and polytheistic worship of elemental spirits imbued within nature, kami (神, “deity”). Its practitioners venerate a communal harmony between humans and their ecology—and harmony with kami in turn—that ama evoke in their ancient diving tradition. As the globe lurches towards the first human-caused mass extinction event, like some of the plant and wildlife species they hunt, ama are themselves becoming an endangered species. Exploring these ideas in the midst of the climate crisis, Katsugi celebrates a feminine symbiosis of humans shaped by and into their ecology.

This conversation on female agency and ecological kinship flows easily between the collaborators. Porter has done multiple residencies in Japan exploring hybrid beings in Japanese folklore and mythology, where her multimedia work – including painting, embroidery, installation, and performance – has often explored transfusions of the human form and natural world. Ohno’s photos of her life as an ama embody the women’s intimate relationship with the sea from their own perspective, while Porter’s surrealism illustrates the transformational effects of that relationship.

Zoe Porter and Aiko Ohno, Katsugi/Dive, onespace, Brisbane, 10 December – 18 December 2021

About Zoe Devenport

Zoe Devenport is an emerging writer, editor, and historian educated at the University of Queensland. She is the founding editor of the academic magazine Footnote Journal, published with the UQ Modern History Society, and an editor for Panoramic Magazine, a global publication run by students at the University of Cambridge. Zoe graduated with a Bachelor of Arts Honours (Class I) in History (minoring in Art History), where her research into the contributions of women to Australian lifesaving is being developed into a potential publication.

Zoe Devenport is an emerging writer, editor, and historian educated at the University of Queensland. She is the founding editor of the academic magazine Footnote Journal, published with the UQ Modern History Society, and an editor for Panoramic Magazine, a global publication run by students at the University of Cambridge. Zoe graduated with a Bachelor of Arts Honours (Class I) in History (minoring in Art History), where her research into the contributions of women to Australian lifesaving is being developed into a potential publication.