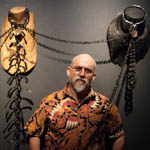

Dominic White collared, Installation view, Current: Gail Mabo, Lisa Waup, Dominic White, QUT Art Museum, Meanjin/Brisbane, 2024; photo: Louis Lim

Dominic White continues the dance of his forebears with a material art that rediscovers Country.

(A message to the reader.)

I am not always comfortable writing on the page. Generally, I make holdable things. When making words, usually, I can see my intended audience as students in the classroom or during a talk at a gallery or cultural place. When writing I cannot see my words land nor see if we are understanding. In this text, I rhythmically bounce from one context and place-scape to another, hopefully creating wholistic insight into my artmaking and thinking process. My history and blood lineage means I can talk about Blakness from my personal perspective and in broad conceptual brushstrokes, with a caveat of flawed understanding and tentative projection. In writing this there is vulnerability, and the permanency of words on a page that only mark my understanding as I type at this point in time. My cultural and personal understanding is changing and growing. There are many influences buried in these words. The brail of country is key, to being in place.

We, you and I, are going for a walk-dance through my country.

A beat has started.

thud

I am an adopted kid. This means aged six-months-old, my name was legally changed to Dominic White, a name chosen by parents Rose and Nat, who I was given to, and who were given to me. In this home, I am loved. I have been theirs since I was four weeks old, like a pup.

I have always had two mothers, two fathers and now, oddly, three sets of parents and three sets of siblings. My birth parents have always been present in me, in the mirror, in the speculation of myself and with others, and in contrast to my family growing up. This is the way of many with ‘untidy’ histories. It is good to know almost all of them now outside the mirror.

Both my mothers danced and value dance.

Dun dun der, dun den dur

Others get to see your origins before you do.

I am 23 in the Museum of Tasmania. My friend Holly points to a painting of an Aboriginal Tasmanian man. ‘That’s you,’ she says with conviction. ‘Nahh… it could be I guess?’

Is that why Tasmania made my skin tingle and body vibrate with something more? Holly was renting in Gladstone on Trawoolway country. I had been home before I knew it. Odd to think about that thirty years later.

Thrum thrum thrum

Recently I have used the metaphor of a Hemiphytes to describe my growing. It’s a plant that starts its life up a tree (epiphyte) and sends roots searching and when its roots find detritus or nutrients in a tree fork, they dig in. Any food in a precarious spot is welcome. Hemiphytes keep sending roots down until they reach the soil, then they shoot for the sun and, using another tree’s structure, form a conduit between the soil and the sun.

It took me a while to connect with the ground.

Swish swish swish thud

Years ago, before I had met my birth mum Joan, I wrote a thesis that had three columns to a page. The central text was the academic script and either side was narrative and sketches or poetry. I was frustrated at the time by the singularity of driving an academic argument. All sharp points and false sequential narrative. This structure has power, yet lacks a wider context and depth. So today I am experimenting further.

A foot fall puff dust

I am talking to Hazel; we have never met before. It is after an artists’ talk as part of the touring show CURRENT, and we are at Queensland University of Technology Art Museum. We have been talking about one of my works Collared that explores slave collars from the Roman Empire to invasive Europeans in Australia, chains about country men’s necks, and our current “white collar” slavery.

I say to Hazel, “We are all connected to slaves by our undies,” meaning that the folk who make our undies (or anything else we buy and own from most big corporations), probably worked in slave-like conditions, and we benefit. It is unavoidable, this cruel disparity of privilege and inequality. I am trying, in an unfair way, to understand the conundrum of present history. The history that is present from the past in the now. I want to process and understand what put Hazel and me in a place-time where we are ethically compromised or conflicted. And how this is as a state of humanness, and how this relates to our country’s historical context and current bilious ‘No’ vote.

Foot thud

Ultimately, I make things to understand my context and process the information that is becoming part of me. I am sawing thumb-thick dry eucalypt branches about thumb length. I need about 17 of them. Do you see the wood dust fall with the rhythm of the saw? I can smell spotted gum.

voop vooopahh voopah

I watch his bright eye twinkle. I have brought two stainless steel trays with me to QUT Art Museum as part of the work I am presenting with CURRENT. One is about 120cm and the other is about 60cm tall, and they are both generic shield-shape. I am smiling with the artist and Murri man Norton Fredericks. We are finding commonality. The trays were first exhibited at McClelland Sculpture Park filled with clay from the park and red hill soil collected from the farm where I lived, worked and grew. Places I wanted to shield and protect, a part of Bunnarong/Boonwurung country that raised me.

I spent hours in the nearby bush, making bows, rafts, climbing trees, fishing, yabbying, building cubbies with bailers’ twine and a hatchet. The bush was a part of me even then, it licked my wounds, listened to my reasoning, soothed the disconnected aloneness of being. My curiosity and romantic dreamings flourished from red hill soil.

In winter you could grow three inches by walking in the mud in gumboots. In the hot summer, the dam and the dust soothed the cracking. I learnt the concept of terroir, wine from a particular bit of land, its flavours captured in a bottle of wine or the taste of a fish.

- Dominic White, Shieldscape, installation view, CURRENT: Current: Gail Mabo, Lisa Waup, Dominic White, McClelland Sculpture Park, 2023; photo: dominic white

- Dominic White, Shieldscape, installation view, CURRENT: Current: Gail Mabo, Lisa Waup, Dominic White, McClelland Sculpture Park, 2023; photo: dominic white

Squelch swelch squish squelch

Near my own country, Trawoolway country as I understand it, I am beginning what will be a collaboration with the artist and cultural leader, Elder Dave Mangenner Gough, and I filled one tray with bivalve shells that have been washed and blown up on Mungiabittas country, Panatana. It’s a bit of country now in the custodianship of the Six Rivers Aboriginal Corporation. Dave and I share parts of our blood line and I walk on familiar and unfamiliar places that hold our stories. Writing this brings tears of absence and reconnection to cultural land. Dave’s Welcome is profound for me, quietly echoing inside, making connections over time that awaken unexpectedly.

This plot of land had to be purchased. The concept of land being bought and sold jangles in my head-heart. Once owned, land can be trammelled, cut, scraped, fenced, restricted by law, and the community that lives around has limited say in how it is used. “Developed”: its nurturance stolen, the diversity mismanaged and the obligation and relationships of Blak Law banished for profit. The bush on this block was probably saved by poor soil. And the springs and costal swamp, mixed woodland continued on without our hands as part of a healthy country. It’s warming to see land and connection revitalised to mob.

Dominic White, Shieldscape collaboration with Dave mangenner Gough, Instillation view, CURRENT: Current: Gail Mabo, Lisa Waup, Dominic White Devonport Art Gallery

The shield tray, along with the other selected works part of CURRENT, is shown at Devonport Regional Gallery, part of the Paranaple Arts Centre. The shells blown together, hold stories of tiny molluscs, collecting centuries and people present and gone simultaneously.

Cheeeiii shhhiiiiy crishhhy

Norton is responding to my trays offered as a prompt. I am a long way from where I grew up and I see the sweep of Bass Strait looking across to my country. This is someone else’s place. I am a stranger here and cannot talk of what needs protecting and of connection. I see the shield tray a bit like a message stick, something to be received then added to and moved on. Each place they go to needs this kind of interaction. I hope Norton and I can find a way of keeping the trays honest and with local rootlings.

Norton’s practice, “Retritus”, uses local plant bush materials to stain, dye and fix colour on silk and linen. His work is softer and flows with tropical creek water and river currents. I add the structure of hut using cane and bamboo “borrowed” from the botanical gardens. The form is of a gathering Hut Hall of which I have heard and seen smaller reconstructions. One was documented by controversial and flawed invader Robinson as being 11m long with enough room for thirty or forty people. Norton’s fabric covers the bamboo shell and tray floor to give the structure form. It is luminous in its welcome. It is good to connect with a local younger artist with a different holding of connection. There is poetry in the work. Within the process of making is the growing of relationship, friendship and depth.

Dominic White, Shieldscape collaboration with Norton Fredericks Installation view, Current: Gail Mabo, Lisa Waup, Dominic White, QUT Art Museum, Meanjin/Brisbane, 2024. Photo by Louis Lim.Art Museum, Meanjin/Brisbane, 2024; photo: Louis Lim

Natter yarn natter yack

Dominic White, Shieldscape collaboration with Norton Fredericks Installation view, Current: Gail Mabo, Lisa Waup, Dominic White, QUT Art Museum, Meanjin/Brisbane, 2024; photo: Louis Lim

In the smaller tray linen is folded and coiled. Sheoak (allocasurina) is framing and balanced above the shield tray. An unlikely coat of arms. These trees comb the air currents in all the countries the show will visit. The soft needles comfort and insulate bums (mooms), form spearheads, are helpful in starting fires and cooking shellfish. A cultural plant from the Top End to Tasmania. Always back to placescape, landscape, country and the mnemonic laying down of depth as we fleetingly be. The everywhen is making fertile soil for humans.

Brisbane’s place rhythm is new to me: wind, river insects chitter, lizards skitter and bats screech. This exhibition with Gail Mabo and Lisa Waup has two other places to travel to: the Australian Design Centre Sydney and Benalla Art Gallery. I hope to work with folk in those places too. There is a loneliness and ego in presenting solo work. Working with others is centring and feels right culturally. The schism of solo artists and collective creative is tension in my practice, training and heart. Perhaps that’s why I enjoy teaching so much.

Creekie tinkle Splops shhhhhhhhwwwwhshhhhhhshs

We are standing on a curb in Mornington, south of Melbourne. I am looking at the place opposite. It has gone now, yet the Mornington Youth Club was here once. Modern boxes of terrace units now occupy. It’s present in my head-heart. A place where my mum (Rose) taught calisthenics, a kind or formulaic dance exercise for “girls” (said in a rising no nonsense teacher voice). It is also where I learnt Judo. I can hear my Aunty Lorraine, mother’s and grandmother’s directive instructive voices saying, “One, two, three, four, OH knees up Michelle”. The classical and folk music which was my growing-up context, the rattling of the walls and the choreographed thud of marches, and the swish of expressive dance called PLASTICS… “Smile girls, one-two, one and two”.

Thrum thrum, thrum thrum

I can also hear a thud as I break fall on to a dust and sweat-laden canvas as my Judo partner practices a Uki goshi (浮腰): Floating hip throw.

Oh, and there is the Bluelight disco too. My teen self, trying to dress cool and dancing with the girls, a rarity for a fella to dance rather than limp from foot to foot in a vaguely rhythmic way. Fergal Sharky and Peter Garret directing my feet with absurd contrast.

Thud Thud sweep tap thud

Look here now, I am barefoot, sitting amongst orchids and lilies in a sculpture park talking to an elder and artist from the central desert who has travelled down south for a residency. He is talking about the importance of touching country with skin, bare feet and moom. We are at McClelland Gallery and Sculpture Park where the CURRENT exhibition has recently opened and my work is on show inside.

Back to outside, Uncle Robert talks about the dance of dust, of footfall during dance/ceremony activating and thrumming into country, making it whole and right. The action of dance is needed so the country can hear his people’s care. We are not related. I think of him as Uncle and Elder given his thoughtful guidance, brimming engagement, deep cultural knowledge and authority. I can hear the clap stick striking and following the feet.

Click, click, click, dust thud

Come into my partner’s garage. I have built a portable jewellery bench in the corner, in front of her car, under the window. Salvaged copper wire is being twisted into loops 3 to 5mm in diameter. I have drilled holes lengthwise through my thumb-sized bit of branch. The patterns beneath the bark are ridged and I feel them with my thumb. The wire loops are threaded through the bits of wood one at a time. One loop is joined to another. They woodenly clink.

Clink clink clinkity clink

I am looking at a page in my sketchbook. A mind map to help guide this writing connects in front of me. I am tracing the line between hypocrite and truth. I am thinking about the conversation with Hazel. How in my youth I might have called these two grey manes “hypocrites” for not doing more. That we both care for moral and ethical truths and abhor the suffering of others for our advantage yet buy undies and are compromised. A younger me might have felt contempt. I wonder how the word hypocrite removes someone’s ability to moderate, adapt, negotiate and live with the truth of our lives. The purity of youthful idealistic thinking tries to force the world into a simplistic idiocy, when used in its judgemental form.

I am on country with my twenty-year-old son. We have come to be part of Mannalargenner Day and he and I probably now have covid. We are in a cheap campervan camping on Homestead Road. Looking out from Ransons Beach is Cape Portland where the celebration of our ancestor is taking place. I am sad that I am not meeting with friends, others of shared lines and history, and cultural practice. And I am joyful we are here on this beach together. I have hopes that my connection and sense of self, will be important to my two boys. It has certainly made me a better man and father for the two of them.

There are deep cultural sites full of occupation, laughter, sand stories and culture right here on this spot and that spot. The everywhen is present and close. I know the familiarity of kin now. The laugh of my sister who knows my humour before we knew each other. The decisions of Mac, my grandfather, whose knife I hold and use, full of his decisions and making ability and thrift. My roots and feet dig into the soil-shell, grit sand. My son and I swing in hammocks in the sun. Snotty and full of clean, clear air. He shares the latest music to capture him as we swing and motored along the skinny bent roads that follow old lines. As we recover, we fish and move through scrub as energy will allow.

I am horrified and saddened to watch a 4X4 power through beach sand and dunes. I later find out our old people are buried in the dunes, their bones and skulls exposed by tire and wheel in such selfish ego-fuelled antics. The 4×4 almost bogged now is turning back the way it has come leaving gouges and breaking in its wake. What sort of people are these? I think that is an old question for my kin. Yet my kin are them as well. There is a structure of thinking that allows this transgression. It rasps the eyes to watch. Compassion is sometimes abrasive. It wears away to expose yourself.

- Artist’s son fishing, waterhouse conservation park; photo: Dominic White

- Boots hammock and covid, Waterhouse conservation park; photo: Dominic White; photo: Dominic White

Stamp turn stamp dust raise thud

On this page of my sketch book is also written “gentleman” and “noble savage”. The romantic aspects of these labels hide the desperate truth of an invasive colonial culture. The politeness and education that allows the colonial project to be waged by the crown and self-interest, behind the veneer of religiousness and Darwinism’s unenlightened use continues destructive myth-making at this time.

The colonial thought projection of innocence and incapability of “Indians, noble savages” removes both agencies to “own land” allowing Terra nullius and the agency for the land/country by the folk who worked with long knowledge, were killed, harassed and removed. It took a particular mindset to be blind to law and lore that is deep and of a continent for many nations and people. It is interesting at a slow change of perception; fire stick lore becomes important as bushfires get hotter. It is still hard for many to see wisdom. The generosity of mob continues.

Crackle crackle crackle

I sit next to my partner. I am watching dignified Marcia Laughton and Rachel Perkins, in a pub in Flinders on the Mornington Peninsula, a few weeks prior to the referendum vote. With a Liberal party ally they explain the structure and goals of the “Yes” campaign. The audience is either those convinced of “yes” or small “L” liberals trying to negotiate their world view and understand the proposition, mostly with generosity. There is a divide in language use here: populist and academic intellectual depth, trying to share First Nations’ thought process. Trying to push the English language to explain a trust in a structural process of yarn and decision making. It could be called “in process we trust”, and language dances to balance point. The acute, patient, polite, clear assertion of a “voice to be heard” is admirable, poetic in its complexity, and intent. The personal toll is visible in my heroes’ eyes. There is sadness here.

Yap Yap Tap yap

Deep dance here as metaphor and practical action. A pounding for renewal and change. The contrast between a Western dance for entertainment and performance, and a First Nations cultural dance being about giving, receiving and education as a form of renewal. I wonder what happened to other cultures that allowed process or renewal to be eclipsed by performance. Is that how Morris dancing in the UK broke down to a quaint folk dance? I wonder at how the need for humans to dance and connect and renew could be missed and dismissed. I think about the First Nation folk who are employed as performers, who then dance ceremony or reconnect with the rhythm of place as part of economic survival. Much like me selling artwork. I wonder who sees what in such performance. I wonder about the land speaking back as footfall and the tuning into place. How that happens when I have walked on my own distant country of the Trawoolway a partial stranger. We all dance across our lives, it’s just a matter of why, for whom or who watches, and what choices we face.

Jiggle jiggle wiggle wiggle stomp

My artwork is coming along now. See an angled branch, mounted upright like a tree on a flat board. Extending past the end of the stick a twist of springy copper wire. Between the plank and the top part of the wire is a Limberjack or Jigg-doll. By tapping the top wire, the doll dances from its neck. A grim adaption from the folk toy. I feel a rich theme opening. Not finished, yet dancing.

Clink clapple clink

Limberjack and jig dolls were also made by my birth Grandpa Mac, whom I never met. I have been shown his dolls and heard from my brother, sisters, and cousins, how he made them. And then made them dance on a board. According to family, we are similar: Mac and I. I hold that connection closely, fertile ground for my roots.

Google searches reveal Limberjacks were made across colonial countries. A rhythmic performance toy, animated by adults. One doll online is poignant, showing a carefully made figure with an African body shape in an African dress, hand carved, for sale in a West Virginian antique store. The face is beautifully carved, it seems to have knowledge and love in the making. I wonder at its history and origins. I wonder who saw it dance in the 19th century when it was made. I wonder at feet dancing far from home and connection. A dancing joy of relief in music. There are Black minstrel dolls as well, all gollywog in their historical hateful condescending parody.

Crack crack crack

So my next theme or curious path is found. I, and perhaps we, will explore the Limberjack. The creative transition from one thought line and object to another is made. Now the process of collecting resources, finding funding, getting a gallery interested, begins.

We all dance, sometimes in love and renewal, sometimes for others, sometimes for cash and the joy of it. My partner Anna (a trained dancer) reminds me of the grace of dancing. I like the word grace and its meanings; as it is the ability to live well with horror and discomfort, and also to move with poetry through the world. I like the double meaning in jig/jigg as a dance and as a tool used to make other things in a workshop.

Swish, swirl, swish

Back to Hazel and my conversation about slavery and hypocrisy. There is no solid answer. We just dance, as best we can, for as long as we can, with grace and intent. Hopefully, our personal dance is connected deeply, and not just about us, but about joy from the sheer pleasure of living.

Finally, the jigs and reels from part of my genetic line mingle with soil talk, with country being renewed. Both my mothers danced. I have yet to dance on country. And still my feet remember walking sand and coastal grass in northeast trouwanna/ lutriwita (Tasmania), a swimming hole and farm my Grandpa Mac grew up on below Mt Rowland, the red volcanic soil of the farm that nurtured me in my youth on the Mornington Peninsula, that still clings to my imagined gumboots. A thrumming recognition of rooted soil. There were many years of thinking, before stepping into mob and a path of heritage that I couldn’t be without now.

Can you and I, dear reader, speculate on how we will choose to, and be made to, dance in the future? With whom, and how, and where, will we dance?

About Dominic White

I am a Palawa, Trawoolway man, descendant of the Tyereelore, through my birth mother’s family. I am an adopted Kid and have been following a process of reclamation of my heritage. I work as a multi-disciplinary artist exploring, connection, observation, responsibility, and obligation in different mediums. My work tries to understand the cultural, historical human activities and interaction with first nations people and thought, place and materials. Often the material cultural context informs the work. Trained as a Printmaker, my work spans contemporary Printmaking, Sculpture, Photography, Performative acts and contemporary Jewellery and design. I am based in Bunnerong /Boonwurung country (Mornington Peninsula), father of two and teach art to support my art-making. Portrait image by Alisha Davenport.

I am a Palawa, Trawoolway man, descendant of the Tyereelore, through my birth mother’s family. I am an adopted Kid and have been following a process of reclamation of my heritage. I work as a multi-disciplinary artist exploring, connection, observation, responsibility, and obligation in different mediums. My work tries to understand the cultural, historical human activities and interaction with first nations people and thought, place and materials. Often the material cultural context informs the work. Trained as a Printmaker, my work spans contemporary Printmaking, Sculpture, Photography, Performative acts and contemporary Jewellery and design. I am based in Bunnerong /Boonwurung country (Mornington Peninsula), father of two and teach art to support my art-making. Portrait image by Alisha Davenport.

Comments

I am blown away by the depth of thought that informs Dominic’s expression of his life journey so far. AND I am his mother, Rose, who had no idea of his heritage when he joined our family aged 5 weeks.