All basketry mentioned in the article. Sapa and pote lo’o (left), codhu (right. h 35 d 30 cm), small kenda with black dhudhu lo’o on top (middle. h 6,5 d 13 cm). Kéka with dhudhu wati inside (right. h 35 d 30 cm). Kenda, dhudhu, kéka, and codhu, are made with crazy weave.

Stefan and Magnus Danerek visit friends on a tiny volcanic Indonesian island, with unique “crazy weave” baskets.

(A message to the reader.)

Translation: “Greetings to all of you! My name is Mboe Erixon, from kampong Mata mere, Palu’e Island. We can make handicraft or exhibits made of natural material, that is basketry made of lontar palm leaves. The lontar leaves are cut even and then further furnished to a certain size. Then they are plaited to a basket of the desired size. If you want to know more, please contact this number: 082237672443 (Cawa [SD], you may also contact Mboe directly using Indonesian on +6281246165822). Mbola so (Thank you)!”

It is late in the morning a day at the end of the wet season. The air is heavy, signalling rain, but it’s not a gloomy day at all. We are happy to have arrived in the mountain hamlet Wolondopo after a half-hour long motorcycle trip on steep and winding cement roads, passing through several villages and a landscape of green slopes with fresh traces of slash and burn.

Palu’e villages are often built on hilltops, and the topography creates long distances between villages. Even though a bird’s route to Wolondopo from Mata mere, the mountain village we departed from, is but a two kilometres flight, hiking there takes a couple of hours along narrow paths up and down steep hills with dense vegetation, both planted and wild. A quick stretch and a few breaths later, we continue quietly upwards by foot in the direction of the mountain, passing unpainted houses of cement and stone with bamboo walls and tin roofs. On the slopes to the left and right grow maize and yams, cashew trees hover behind the furthest house, our aim, and after which there are no more settlements.

Two youths greet us casually when we enter the house yard, before a familiar voice happily cries out “Santa Maria!” The voice belongs to our charismatic but unassuming host of the day, Mama Roja. Relieved that she is not out tending to the family plantations today, we return her greeting with big smiles. Roja promptly asks us to sit down by the woga, a long platform or table of bamboo, before asking Mboe, one of our drivers, to shoot one of their free-range chickens, who immediately sense fear and flutter away in different directions. The somewhat dramatic hunt with bow and arrow ends with Roja and her sister Nina cooking both boiled and fried chicken. The chicken is served with rice and washed down with a shot of distilled lontar juice, as custom demands when kindred or long-distance guests are visiting.

Roja’s family are farmers, working on their own land. Roja is known for being clairvoyant and being right about most things under the Palu’e sky. Candid and shy, with strong memory, intuition and faith, she does not flaunt her abilities, to which plaiting beautiful basketry belongs. And this time basketry is the main reason behind our visit to Roja and the hamlet, which is part of the customary land (tana) of Edo and the administrative village Keso-Koja.

Palu’e only has a diameter of about seven km in each quarter and is actually a mountain with an active volcano that rises out of the sea to 900 m altitude. The island is visible from the Flores north coast and accessible by passenger boat from the Sikka regency capitol Maumere, about a five-hour journey. The approximately 10 000 inhabitants speak sara Lu’a, an Austronesian language of the Central Flores group. They live primarily from horticulture and fishing, but especially the men work longer periods outside of the island, sometimes for several years in Malaysia in various industries. Traditional crops are tubers, maize, and beans, especially the mung bean. Cashew is a relatively new cash crop.

Palu’e is surprisingly fertile despite lacking fresh water and the short rainy season (Dec-Feb). That thousands of people have been able to survive there is remarkable. A report on this from the 1860s was strongly disputed by members of the Royal Geographical Society: “a total impossibility”. What sustained the estimated 5000 inhabitants, noted the author of the report (Cameron), was the lontar palm (Borassus flabellites), or koli in sara Lu’a. This tree is very important, if not vital, also to other cultures in eastern Indonesia, such as the Savunese. The lontar palm can through a sophisticated process be tapped for its mildly intoxicating juice (dua. Ind. tuak) both morning and evening. Depending on the season and the number of flowering branches tapped, a single large palm can yield over twenty litres of juice a day for several months.

As water tanks have been built adjacent to the houses dependence on the lontar juice has decreased. The ancestral ban on the distillation of lontar juice to arrack is still adhered to. To break it would lead to a natural disaster, and therefore arrack is imported from Flores. The prohibition reflects how dependent the Palu’e have been on lontar for fluid, as well as their respect for nature.

Animals and plants, the deceased and the living, are all interconnected in Palu’e thought. The ancestors are revered and feared, and they, after less than a century of Catholicism, continue to exact punishment for the breaking of custom, including misbehaving in human affairs, or, in the seven domains of “buffalo blood” for digging, building, and felling trees during one of the two five-year agricultural cycles. The landscape is riddled with place names, word pairs mentioned in customary prayers, and spirits attach to certain rocks or old trees in the spiritual landscape, but the young or the more modern tend to forget about these things.

The observant eye will notice certain signs, usually made of natural fibres, hanging from a tree in the plantations. These are huru, prohibitions enforced by a curse, inherited formulas that come in many forms depending on the owner’s ancestor. A person who picks fruit without permission can become ill with symptoms according to the named formula, and must come to the owner or another healer who has the formula for the designated cure. A huru is often named after the plant used for the sign or in the cure.

Several species of animals are connected with the ancestors; the crickets, who can signal danger or impending death; the python, possibly a remnant of an ancient snake cult (Nusa Nipa, the local name for Flores, means Snake island), hides in the ceremonial centre and appears in dreams; the rat, who when entering the houses at certain times of the year should be spoken to politely as ”King and Queen” and kindly be asked to go somewhere else, instead of chasing them away, because then they will become a real nuisance; the whale, whose name pu loga signals a connection with the ancestors (pu).

The lontar palm is not planted. New trees are usually left alone when the vegetation is burned before sowing, making the palm a common sight in the landscape. It is versatile: the nutritious fruits can be used to feed pigs, the wood is used as lumber, and the long leaves are an excellent material for plaiting basketry. Lontar baskets are made throughout the island and all households use them, but the people of Edo have a local reputation for being particularly skilled at basket making. Perhaps it is so because only a few women in this area weave, which is more or less mandatory in the other, buffalo sacrificing, villages of the interior. Baskets are made by women, who, among else, use them to gather and store the agricultural produce that they are responsible for. The men’s task in this context is to climb the lontar palms and cut off the long branches, but there are men who are able to plait fancy hats.

After the shared meal at Roja’s house, we take a leisurely stroll and discover several lontar baskets resting on the ceramic-covered graves behind the house. On Palu’e, as on Flores, the tradition is to bury family members near the house, and it’s not uncommon to see people sitting, sipping coffee or resting on the graves. On the wall outside of Roja’s kitchen are yellow-green lontar leaves hung to dry. A few hours in the sun are enough. Dried lontar leaves are white-yellow but the ready basket is often coloured by hanging it over the stove until the desired colour, yellow, brown, even almost black, is achieved. If the smoking is done with caution, an appealing colour is created and the material becomes more durable, not seldom with a whiff of the salted pig fat that is kept and smoked above the stove.

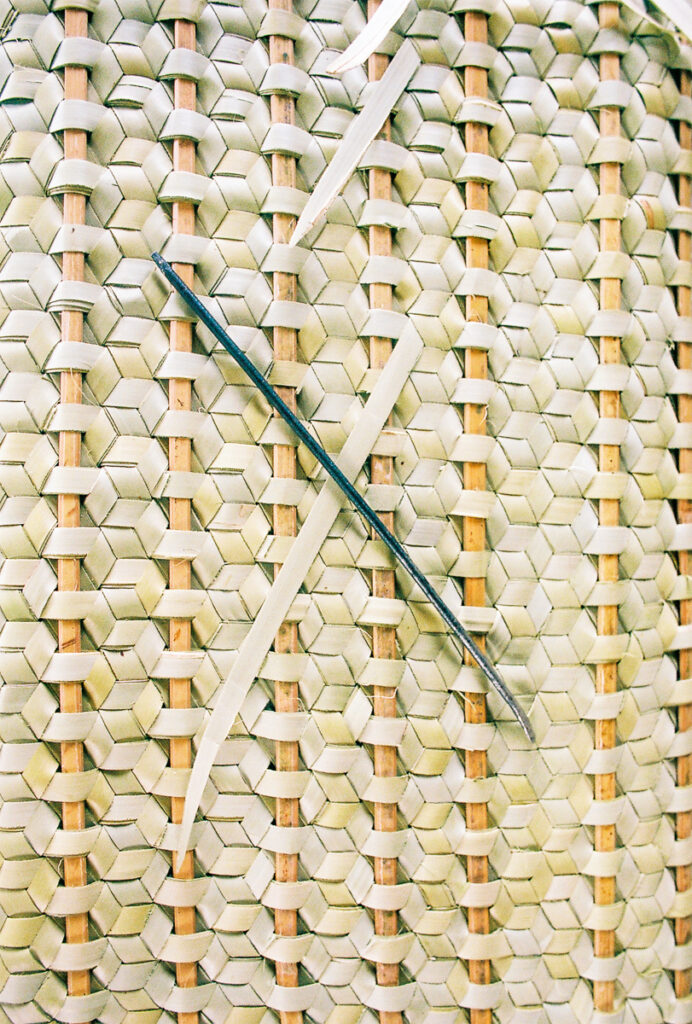

Roja has plaited two kinds of baskets for us: kenda, a rectangular coffin-like type, used among else to store valuable textiles, and dhudhu, a round hexagonal type often used to store beans. Both are made with the same technique, called anyam gila in Indonesian, or “crazy weave” in English, a three-stringed technique known from the Indonesian archipelago. The name, we infer, comes from the complicated process that can drive the maker crazy.

Roja is photogenic but prefers to be photographed on Sundays when she is not dressed for daily work. When displaying the baskets, Roja explains that she always uses two strands of fibres, forming one element, for durability. She performs a quick demonstration of crazy weave by plaiting a fire fan, li, the simplest object made with this technique. Because the word li also means “crazy”, she gives us the tool with a smile and a warning, “Do not use it to fan the face, because then you may become crazy”.

We ask Roja who taught her the basket plaiting skills. “Here in the Edo territory, everybody (women) can make baskets, but everyone cannot make kenda. I was taught by my mother and my grandmother.” Plaiting baskets is primarily learned at home, but also from the surroundings. Roja plaits baskets for the needs of the house, but also for others. “If relatives come to visit, they usually ask for baskets. Fortunately, I was able to save these for you.”

Master maker Mama Roja photographed on a previous occasion (a Sunday) when narrating Palu’e oral traditions. She demonstrates how to make a sign of lontar leaf used for the protection of crops (huru koli).

Palu’e baskets have a defined base, body, and rim. Lids have the same shape as the container. The rim is often visually or structurally set apart, supported by a thicker, hidden, string of coconut palm leaf. Generally, double strands of fibres are used. In the first step, the leaves are cut to straight strands with a fine knife. The plaiting is done with the fingers only or with the help of an awl. The most common techniques for interlacing the fibre strands are variants of checker work and crazy weave. In the former, two strings cross each other at straight angles. Over one under one is the simplest technique. On most baskets the strips run at 45° left and right. When the strips go over two under two, and where one strip goes under and the parallel neighbour over, a zigzag twill pattern is created. Both methods are sophisticated when using thin narrow strands, resulting in a fine dense surface as on pote lo’o that can be made with both methods. On pote lo’o, the strips change direction (90°) at both base and rim, which is both decorative and stabilising.

This unlidded basket is more rectangular than cylindrical (rounded corners) and its volume is about four-five litres. It is used for small things, often the areca nuts and betel fruits so many women are fond of chewing. Pote lo’o has eight, tight, layers of smaller baskets inside, made with wider strands and simple inclined checker work. The layers make the basket sturdy and can be used to hide slim objects. Pote lo’o is the only basket that is decorated with additional materials, such as beads, to be used ceremonially.

Sapa is similar to pote lo’o but larger, and more flexible and cylindrical. It is made with simple inclined checker work and the reinforcement is limited to a row with extra flaps five cm below the rim. Sapa is used to carry firewood or, for example, store a dozen kilograms of beans. The volume of a sapa is often about 15 l but it can be considerably larger.

The crazy weave is a triaxial type of twill that creates a neat, dense surface of hexagonal units with three visual rhombuses. Because the work begins with three strings crossing each other at 60°, the foundation is a six-pointed star where each strip serves as a hub for the next interlacing in both directions. The resulting object naturally gets a hexagonal shape. Dhudhu, normally used to store beans, is done with this technique. Dhudhu wati, or dhudhu séra, has a round hexagonal shape with six protruding corners on the base (container and lid). The height of the lid is a cm shorter than the container, and the corners can be given additional insertions to enlarge them, which is both decorative and stabilising, and sometimes small towers are added.

Decoration on the crazy weave basketry tends to be limited to the patterns made by folding strips into small three-dimensional triangles, séra, that cover half of the rhombic shape underneath, as seen on kenda and dhudhu wati/séra. The volume of a dhudhu (container) varies from one to four litres but often it is about three litres. Dhudhu lo’o (“small dhudhu”) refers to a smaller dhudhu with a flat base.

With additional insertions and twists, it is possible to create rectangular shapes also with crazy weave. Only a few of those who can make hexagonal baskets can plait rectangular shapes, especially larger ones. An English lady, Mrs Bland, reported already in 1909 from the Malay Peninsula that it is difficult to find people who can plait rectangular boxes with crazy weave. On Palu’e this type is called kenda. Kenda are made in different sizes but are often large enough to be called coffin (e.g. h 20 w 30 l 45 cm). The container is rectangular with an almost identical lid. Both are supported by thin bamboo sticks along the sides and decorated with additional triangular insertions. Because it can be filled well over the rim with cloth, it is spacious; the example can hold up to 45 l. We have never seen kenda, or this rectangular type, anywhere else than on Palu’e.

Codhu is another type of basket made with crazy weave. It is round and hexagonal, and the lid has a shorter height than the container. Codhu is used in the house to store anything, but not agricultural products. It is more common in Woja, the coastal area in the south of the island. Codhu are usually quite large (see Fig. 15).

In the afternoon it is time for us to say farewell to Roja and her sister, until we meet again, because we also have friends at the foot of the settlement who are waiting for us. We collect the baskets and find that a dhudhu is filled with mung beans, a gift of the local produce. But just as we are about to descend the dark clouds descend on the hamlet and it becomes foggy in an instant, the palm trees begin to sway in the increasing wind, then the downpour begins. We wait out the rain on the porch to Nina’s house until there is a break, before strolling on toward the house of Toka, the hamlet’s ceremonial leader, and whose family are skilled basket makers. Heavy, sporadic rains are common at this time of year.

Toka gives us a similar welcome with food and drink. A set of baskets, made with us in mind, already sit on the bamboo table. Among the basketry, mostly dhudhu and kenda, is a kéka (see Fig.15), a wide round unlidded crazy weave basket of low height. At Toka’s house, we get the opportunity to see parts of the kenda-making process. Toka and the makers are delighted that we appreciate their craft and would rejoice if someone else “over there” can appreciate it too.

Palu’e basketry has not been traded, it is only exchanged for other goods inter-island, but the people here are open to use their skills to get some extra income. Toka reveals, “Many men in Keso-Koja recently received training in how to make furniture of bamboo from Balinese carpenters”, to add to their existing skills. Toka’s mother is especially adept at making baskets, and smoking them to a pleasant brown colour, and Tia, his wife, has learned how to make kenda. Several young women from the nearby houses are learning the crazy weave technique and how to make kenda from Toka’s mother and another grandmother.

In terms of craftsmanship, the situation in other places on the island is quite different. In some villages, only one or two, or nobody at all, is able to plait kenda. It makes kenda a rare object, and Wolondopo a unique place for the intergenerational preservation of this intangible cultural heritage, the island’s finest basketry, as well as for crazy weave-rectangular baskets of the Indonesian archipelago.

When the day turns into night and the low clouds release a drizzle it is time for us to leave. Toka wishes that we return, and so do we, grateful for the hospitality and knowledge given us. We put plastic and rice bags around the basketry for protection before departing with the same motorbikes and drivers, who are used to the steep and winding Palu’e roads, carefully balancing the precious cargo in our hands as the drizzle intensifies to rain.

Continuity – a girl learns to make kenda with the support of an aunt. Wolondopo, WARLAMI visit, 2019.

Postscript: The year after the described visit we guided WARLAMI (Indonesian Natural Dyes Association) to Palu’e to pinpoint interest in plant dyeing among the island’s ikat weavers. The chairwoman Myra Widiono, a fiery soul who runs Rumah Rakuji (shelter for arts and crafts. Jakarta), took notice of the basketry and the makers’ potential. Just prior to the corona lockdowns we managed to send a number of baskets to Rumah Rakuji, where dhudhu and kenda are now displayed in the gallery. With this, we wish that the basketry artisans of Wolondopo and Palu’e can get some needed extra income and that their skills are encouraged, maintained and transmitted to the next generation.

Rumah Rakuji’s website is www.rumahrakuji.com.

Further readings

Barnes, Ruth. 1993. Southeast Asian basketry. Journal of Museum Ethnography (Baskets of the world) 4:83-102.

Bland, L.E. 1906. A few notes on the ”Anyam Gila” Basket Making at Tanjong Kling, Malacca. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 46:1-8, Plates I- VI.

Cameron, John. 1865. On the Islands of Kalatoa and Puloweh. Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London (9) 2:30-32.

Jasper, J.E. and Mas Pirngadie. 1912. De Inlandsche Kunstnijverheid in Nederlandsch Indie. I: Het Vlechtwerk. s-Gravenhage: Mouton & Co.

About the Stefan and Magnus Danerek

Stefan is a researcher with a background in Indonesian language studies. During 2014-2016 he carried out documentation research of the Palu’e language and oral traditions. Stefan also translates Indonesian fiction for Swedish publishers.

Stefan is a researcher with a background in Indonesian language studies. During 2014-2016 he carried out documentation research of the Palu’e language and oral traditions. Stefan also translates Indonesian fiction for Swedish publishers.

Magnus has a social science background and has worked with identifying traceable supply chains for household products made from natural materials, including traditional or handmade items. He is currently authoring miscellaneous writings while studying Library and Information Science.

Magnus has a social science background and has worked with identifying traceable supply chains for household products made from natural materials, including traditional or handmade items. He is currently authoring miscellaneous writings while studying Library and Information Science.

Stefan and Magnus are based in Sweden and have stayed for extended periods in Indonesia and China. During recent years, they have focused their attention on folk arts and crafts. See Stefan’s and Magnus’ article about ikat weaving ’Palu’e ikat: Nomenclature and iconography’ in Archipel no. 100, 2020. Online version: https://doi.org/10.4000/archipel.2111. See also https://cawalunda.org.

Comments

Dear Stefan and Magnus, Thank you for this wonderful story about the Lontar baskets of Palu’e. Since my early childhood I have loved a small dhudhu my mother used as a sewing basket and wished to learn triaxial weaving. I remember also the smoking of baskets on Lombok when a travelled there in 2000 to learn songket weaving. Your article gives a sense of having visited Palu’e. I do hope this craft will continue undiluted!

Thank u so much for this story , about palu’e.

Thank you, Ilka, and My,

We are happy to hear that you like the article, and, Ilka, you story sounds interesting too!

Wish you well

Stefan

Loved your article and i am so happy that you have shared the beautiful crafts that come from the Indonesian region

Thank you, Joan, for your kind words.

In beauty we trust.

Wish you well,

Magnus