Francisca Gili explores the musical legend of a bone flute played inside a ceramic vessel. How was it made and what did it mean?

Sometimes when I play music, I find a way to travel. I enter a state of deep listening and concentration that allows me to transcend my physical body and enter what I can only describe as another dimension. I later learned that this is called a trance. I have since been fascinated by this experience, constantly seeking to understand it and explore its mysteries. However, no matter how much I try, it remains elusive and difficult to fully grasp. Each time I attempt to delve deeper into this state, I embark on a new adventure filled with learning opportunities. I have come to accept that this journey is one that cannot be fully understood, and that the quest for knowledge itself is one of the most rewarding aspects of the experience.

In my creative work, I developed a passion for making musical instruments and was fascinated by working with clay. This inspired me to explore ancient sound technologies, particularly pre-Hispanic whistling bottles and their various organological variants used to produce sound. Using Andean pottery ontologies, which are ways of understanding being in the world, I created a series of instruments called Cantarino. Each vessel was designed to resemble a living being, and when played in unison, they produced a soundscape that evokes the sounds of nature. This led me to explore the idea that this ancient technology was a means of dialogue between different species, a bridge between nature and culture that allowed for communication through sound.

I am now embarking on a new adventure that has emerged from my experiences with Cantarino. While exploring the sonic possibilities of building these instruments, I discovered that placing a ceramic body on top of a whistle creates a resonant effect that allows for the production of more notes and a beating sound. I collaborated with media artist Nicole L’Huillier to further explore this phenomenon. During this exploration, I was reminded of a myth or musical legend that I heard in Cusco in 2006 called Manchay P’uytu. This tradition involves playing a bone quena inside a large ceramic container, and I began to imagine that a similar resonant effect to what I had discovered could occur with these specimens.

When I first learned about Manchay P’uytu, the discourse surrounding it was that it was an activity linked to sin and was demonized. It was believed that whoever practised it could be affected by madness. For instance, in 1894, Ricardo Palma narrated that “The Catholic Church struck down a greater excommunication against those who sing the Manchay-Puito or play quena inside a pitcher. This prohibition is respected today by the Indians of Cusco, who would not consent to give their souls to the devil for any treasure on earth..”

At that time, I was finishing my undergraduate studies, and I always had a concern to de-colonize my mind. It was precisely for this reason that I chose to do my practice in the heart of the Inca Empire. However, the halo of evil that surrounded the Manchay P’uytu was powerful enough to scare me. For more than fifteen years, I refrained from investigating this tradition of demons. But now, I have finally begun the adventure of investigating this ancient practice.

To continue my story, I must mention a dark mission that the Spanish colony brought with it, which undoubtedly altered many of the traditions that had flourished for millennia in the valleys of our Andes mountain range. These were campaigns to eradicate idolatry that were brought to the New World, where many priests travelled the vast Andean terrain to record all those practices that needed to be eradicated to establish the Catholic order. Often, the collection of this information was associated with removing idols and destroying huacas (sacred places and beings). In these campaigns, all indigenous devotional traditions were treated as profane and designated as evil, linked to sin and the devil.

Therefore, I invite you to shed your prejudices and understand that in this case, the devil is not an infamous being from hell. Instead, it is a deity of a religion other than Catholicism. The demonic, then, is nothing more than what is associated with these other cults that suffered the pain of being stigmatized.

The future of this unfortunate mission to eradicate the ancient devotional practices of our territory was varied. Some practices deemed devilish, like Manchay P’uytu, were stopped. In other cases, despite the fact that the sacred spaces where these customs were performed were burned, destroyed, and replaced by crosses, they continued to be objects of veneration. Community members returned to these places to make payments and communicate with their huacas that still existed and continue to reside in the sacred places (Duviols 1986). They consumed and still consume offerings and reciprocate by offering well-being.

The legend of Manchay P’uytu has been passed down through oral tradition since the viceroyalty era, and there are various accounts of it. Cornejo (2007) has compiled stories and works of art and literature related to the history of Peru, which feature this legend as the protagonist. The story has different versions that have been distributed across several locations in the central and southern Andean region, including Lima, Arequipa, Cusco, and Ayacucho. While some claim that its origin is pre-Columbian (as stated by Lira in 1944, cited in Cornejo’s work), other narratives suggest it is a mestizo tradition.

Most versions of the story tell a tragic tale of love that took place in Yanakiwa, where a priest used Manchay P’uytu sound technology to communicate with his deceased lover Anita, who had died for violating ecclesiastical norms by having a forbidden love affair with the cleric. The priest decides to desecrate Anita’s grave and creates a quena (a type of flute) from her tibia bone, which he plays in large pitchers to generate melodies that allow him to communicate his love to the deceased. Another version of the legend features a young woman named Issicha P’uytu , as described by José María Arguedas in 1949 (cited in Cornejo’s work). Issicha, who was of humble origin, knew how to play the quena made of human bone inside an elongated pitcher. She was appointed to serve a curaca (an Andean authority), who gave her a Manchay P’uytu from which she emitted intense and brilliant melodies. Lira (1974, cited in Cornejo’s work) has suggested that the story of the clergyman is a distortion of the story of Issicha. The latter story has a complex ending, in which the interpretation of the Scarecrow is related to death.

After going through the process of creating a research proposal through creative exploration, I got attracted by a reflection triggered by a description in Deglane’s (1848 in Cornejo 2007) version of this story. In it, the melody of the flute was animated and had the agency to describe to the clergyman how Anita died. This led me to hypothesize that the Manchay P’uytu was a sonic technology that allowed the living and the dead to establish dialogues. However, as I have been telling you, this technology was later stigmatized and associated with sin during the colonial period.

To better understand the Manchay P’uytu tradition, it is important to consider the Andean concept of death, which differs significantly from the Western idea of death. According to Gil García (2002), death and the afterlife are not associated with the notion of a Final Judgment or the concepts of reward and punishment, Heaven and Hell. Rather, post-mortem life is understood by Andean people as a parallel existence in the same terms as life on earth. The dead, also known as ancestors or malquis, are believed to give coherence to the world of the living. The cult and festivities held in their honour allow them to give social cohesion and protection to the communities. The bodies of the dead are considered sacred beings, to which offerings are continually made in their graves. Zuidema (1973) emphasizes that the cult of ancestors constitutes the axis of the Andean religion. These ideas helped me to contextualize the importance of the Manchay P’uytu tradition and its significance as a means of communication between the living and the dead. By exploring the constituent elements of this tradition and stripping away the layers of sin that have been associated with it, I could gain a deeper understanding of its true purpose and significance within Andean culture.

According to Catherine Allen (2014), mummies have been preserved in places of great significance, and encountering these spaces and entities is considered a potent experience. These places are referred to as “wak’as,” an indigenous category that encompasses various realities, including indigenous cemeteries or “machays,” as well as other powerful locations such as stones, mountains, and waters. Wak’as are regarded as living beings with diverse capacities, emotions, and appetites. Therefore, offerings are seen as a ritual feast and an act of commensality or food-sharing. The purpose of these offerings is twofold: to establish a dialogue and to satisfy the hunger and thirst of the mountains, thunder, or, in this case, mummies or ancestors. It is essential to recognize that the offerings are not just symbolic gestures but are understood to have real effects on the wak’as. In other words, they are believed to be reciprocal relationships where both parties benefit.

In 1613, Fray Martín de Murúa recounted that although the clerics who brought the Catholic order forced the burial of the deceased in the churches and cemeteries, the indigenous people: “They dug them up secretly without the news reaching the priests, and they took them to their huacas, to the hills or to their pampas where their ancestors and ancient graves were or in the houses of the deceased. There they kept them to give them their time to eat and drink; and then making meetings with their relatives and friends, they danced and danced with a great party and drunkenness” (Murúa 1613 in Gil García 2002).

Father Pablo José de Arriaga also points out in 1621 that “In many places, and I believe that in all the places where they could, they have removed the bodies of their deceased from the churches and taken them to the fields, to their machays, which are the graves of their ancestors, and the reason they give for removing them from the church, it is as they say Cuyaspa for the love they have for them” (in García 2002).

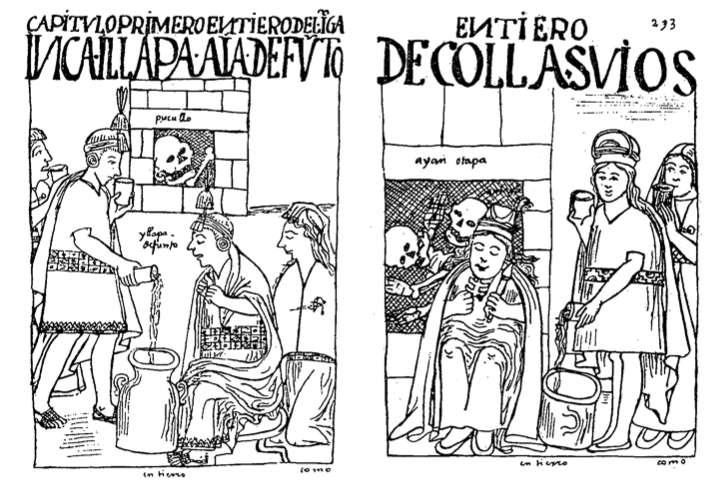

It is interesting to note what Guaman Poma de Ayala also said. He was a mestizo who lived in the 16th century and created a detailed chronicle of Andean life and customs during the Spanish conquest. In one of his drawings, we can see a depiction of a celebration where people are drinking and sharing the festive space with their deceased relatives, represented as skeletons (fig. 1). This illustrates the importance of ancestral worship and the continuity of traditions, even after death, in Andean culture during colonial times

As I read through the narratives previously cited, I couldn’t help but notice and become intrigued by the festive and affectionate nature of the Andean people’s relationship with death. It seems that the possible dialogue with the dead through the Manchay P’uytu may have been centred around love and affection for those who have passed. This is quite different from the devilish tradition that the clergymen likely labelled in their efforts to eradicate it.

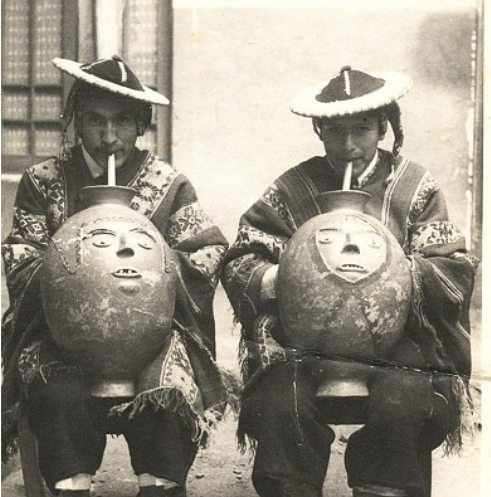

From this starting point, then begins my decolonial sonic mission to explore this ancient tradition of playing the quena inside large ceramic pots. One point to make clear is that there is no physical evidence of these specimens, or at least I have not known. Except for a photograph where two men can be seen playing the quena inside large pitchers and some descriptions. D’Harcourt (1925 in Cornejo 2007) describes that the pitcher had two holes on its sides and that the instrumentalist played the quena passing his hands over the holes in the pitcher at the same time. It is also described in a popular version of Huamanga described by Cornejo (2007). The author narrates that it was a quena that was:“…put into a gourd, specially made of fired clay, with a little water at the bottom, a small hole on the upper side for the quena to enter and two for the two hands to enter…” (Cornejo 2007, p. 85).

Players of Scary Well taken from http://canteradesonidos.blogspot.com/2007/10/manchay-puito-leyendas-de-la-quena-en.html

Inspired by these descriptions, I have created a series of eight large ceramic containers designed to be used as Manchay P’uytu. Each container conceived as a clay being, has its own personality given by its face and clothing. I drew inspiration from various shapes and designs of large-format ceramic containers from Andean and Amazonian archaeology and ethnography, encompassing the postulates of Amerindian Perspectivism proposed by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro (2013), which defines an ontological matrix-way of living and being in the world- common between the Andes and the Amazon lowlands. In this way of thinking, there exists an epistemology of aesthetic quality that operates by attributing subjectivity or “agency” to things. Having this in mind, I created these beings with intention and faith in their ability to act and affect the environments that their melodies travel through.

It is uncertain whether this exploration will provide me with more tools to understand the relationship between trance and music. However, what is certain is that I am embarking on a captivating journey that calls for de-coloniality, challenges my Western-centric perspectives, and offers an avenue for the sheer pleasure of listening to music.

With this proposal, I aim to cultivate a more affective and meaningful relationship with my ancestral territory through sound. That is why I have named it Manchay P’uytu del Mapocho, after the Andean valley where I was born and raised. My dream is for the sounds produced by these ceramic pots to activate something within us, to inspire a more careful, festive, and affectionate way of relating to our ancestors, learning from their heritage, and forging new ways of inhabiting the world that differ from those we have lived in during the Anthropocene.

As Ricardo Palma (1894) wrote, I hope that by playing this music, “my soul is being given away to the demons,” the “devils” of our mountain range better called tirakunas the “beings of the earth” (sensu De La Cadena, 2015). Within this research, through creative exploration, I seek to maybe uncover their treasures through sound, engage in a dialogue with them, and embrace their mysteries. This project is not only a way to explore the ancient tradition of playing the quena inside large ceramic pots but also a decolonial and sonic mission to challenge Western positivist thinking and awaken a new way of relating to the Andean territory in which I live.

I would like to express my gratitude to all those who have contributed to the creation and development of this project. First and foremost, I want to thank FONDART, Artesanía 2021 line, for providing the financial support that has made this proposal a reality. I also want to thank the Chilean Museum of Pre-Columbian Art for their sponsorship of the initiative. I am deeply grateful to La Chimuchina (José Pérez de Arce, Claudio Mercado and Rodolfo Medina) for their creativity and guidance throughout the investigation. The Groff ceramic workshop provided invaluable advice on making enamels and firing the pieces. Magdalena García helped collect the bones for the quenas and Boris Cartagena contributed to making them. Thanks to Emilia Simonetti that made a short film documenting the project, and Nicolás Aguayo that captured the essence of the ceramic beings through his photography. I am grateful to the talented musicians Catalina Menares, Victor Lino Venegas, Clemente Mackay, Diego Villela, and Alejandro López, who were invited to explore the sonic possibilities of these clay beings. Also thanks to Tomás Pérez from La Salitrera who recorded the sounds of the Manchay P’uytu from Mapocho, and Juan Huarancca, my Quechua teacher and announcer in the video. Lastly, I want to thank Kevin Murray for the translation from Spanish to English of this chronicle. Also for his amazing effort to gather stories around crafts, creating an invaluable archive to inspire other ways of knowing, creating and living with objects.

References

Allen. Catherine.. “El Animismo en Los Andes”. Artículo presentado en el Encuentro Internacional “Arqueología y Etnohistoria en Los Andes y Tierras Bajas. Dilemas y miradas complementarias,” Cochabamba- Bolivia. 2015

Cornejo, Marcela. “Manchay Puytu: Leyenda de la quena en las letras y artes peruanas”. Cantera de Sonidos. 2019.

De La Cadena, M. Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice Across Andean. 2015

Duviols, Pierre. Cultura Andina y represión: Procesos y Visitas de Idolatrías y Hechicerías, Cajatambo siglo XVII. Cuzco: Centro de Estudios Rurales Andinos “Bartolomé de las Casas”. 1986.

Espejo, E. 2021. Yanak Uywaña, “La crianza mutua de las Artes”. XLV Coloquio Internacional de Historia del Arte. Epistemologías situadas. 2021

Gil García, F. Anales del Museo de América. Madrid. 10: 59-83. 2002.

Palma, R.Tradiciones Peruanas. Montaner y Simón editores. Barcelona. 1894.

Poma de Ayala, F. G. : Nueva Crónica y buen gobierno [1615] ( J. Murra, R. Adorno y J. L Urioste eds. ). 3 vols. Crónicas de América, 29. Historia 16. Madrid. 1987.

Nielsen, A., C. Angiorama y F. Ávila, Ritual as Interaction with Non- Humans: Prehispanic Mountain Pass Shrines in the Southern Andes. En Rituals of The Past, Rosenfeld, S. & S. Bautista, Eds., pp 241-266. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. 2017.

Taylor, D., Archivo y repertorio. La memoria cultural performática. Santiago: Editorial Universidad Alberto Hurtado. 2015.

Viveiros de Castro, E. La mirada del Jaguar. Introducción al perspectivismo amerindio. Editorial Tinta y Limón, Buenos Aires. 2013.

About Francisca Gili

I am an artist and researcher with a Bachelor of Arts and a Master’s in Anthropology. My work revolves around research, heritage conservation, and contemporary artistic practice. I am particularly interested in Andean aesthetics and performance, and my creative proposals are often inspired by the cultural heritage of this region. Since 2016, I have been focused on contemporary ceramics, creating thematic series that draw from Andean pottery traditions. I am also a member of the La Chimuchina group, which explores the intersection of South Andean musical archeology and contemporary traditional manifestations through sound art. My interdisciplinary background has allowed me to approach my work from multiple angles, and I strive to create projects that bridge the gap between past and present, tradition and innovation. Visit www.franciscagili.cl

I am an artist and researcher with a Bachelor of Arts and a Master’s in Anthropology. My work revolves around research, heritage conservation, and contemporary artistic practice. I am particularly interested in Andean aesthetics and performance, and my creative proposals are often inspired by the cultural heritage of this region. Since 2016, I have been focused on contemporary ceramics, creating thematic series that draw from Andean pottery traditions. I am also a member of the La Chimuchina group, which explores the intersection of South Andean musical archeology and contemporary traditional manifestations through sound art. My interdisciplinary background has allowed me to approach my work from multiple angles, and I strive to create projects that bridge the gap between past and present, tradition and innovation. Visit www.franciscagili.cl

Comments

What a beautiful story. A revelation! Aesthetically a pleasure for both the ear and eye. At first, reading about the bone flutes played in ceramics, I imagined the sound would be sonorous and low – the sound you get from blowing across a bottle. But in the film the thready pitch reminds me of cicadas and birds, rain, water running over stones etc. What a sound picture!