Tarah Hogue reflects on the way Inuvialuk artist Maureen Gruben gathers the materials at hand in her world to create art using techniques passed down by her mother.

(A message to the reader.)

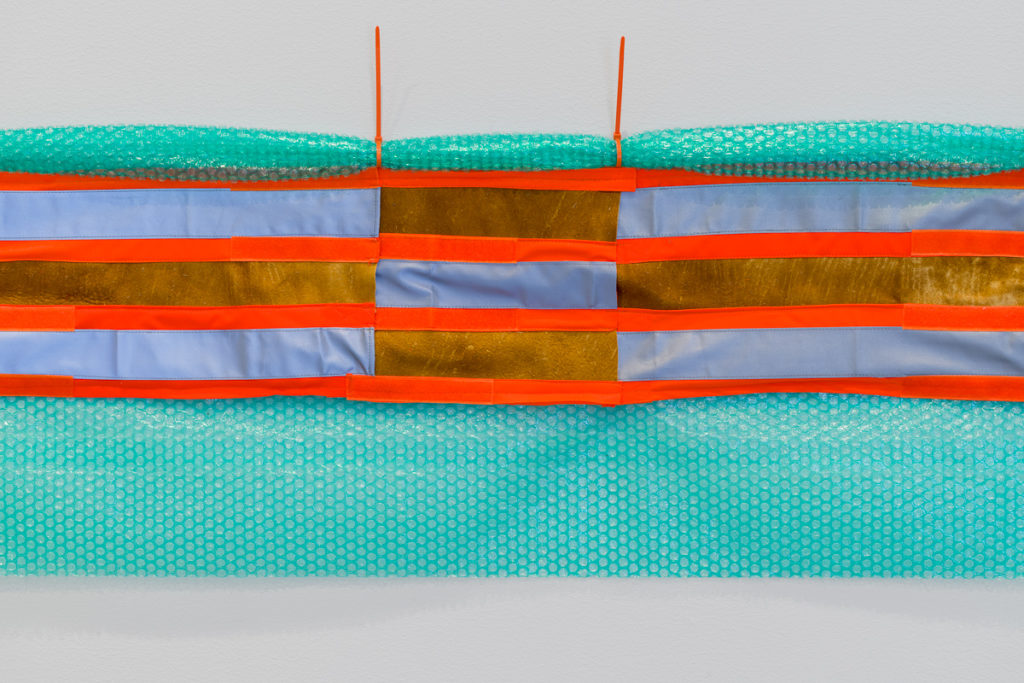

Bubble wrap, reflective tape, Velcro, zip ties and moose hide—a heterogeneous collection of materials picked out of scrap bins, thrift stores and junk drawers. Maureen Gruben’s combinations of gleaned materials articulate an ingenious self-reliance—a repurposing of “what’s available” or readily at hand within the artist’s circular migrations between Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, and Victoria, British Columbia. Partial deer and moose hides for discount prices, scraps of seal skin picked out of landfills and beluga intestine harvested following a hunt, Gruben’s mediums are a product of Inuvialuit subsistence on the Arctic coast in the twenty-first century as well as reliant on that which is discarded and no longer considered for its use value. The narratives attached to her source materials inevitably become encoded in Gruben’s artworks, which, in gathering together “natural” (primarily from animals) and mass-manufactured materials, evoke urgencies and intimacies within cultural knowledge, kinship and Northern ecosystems.

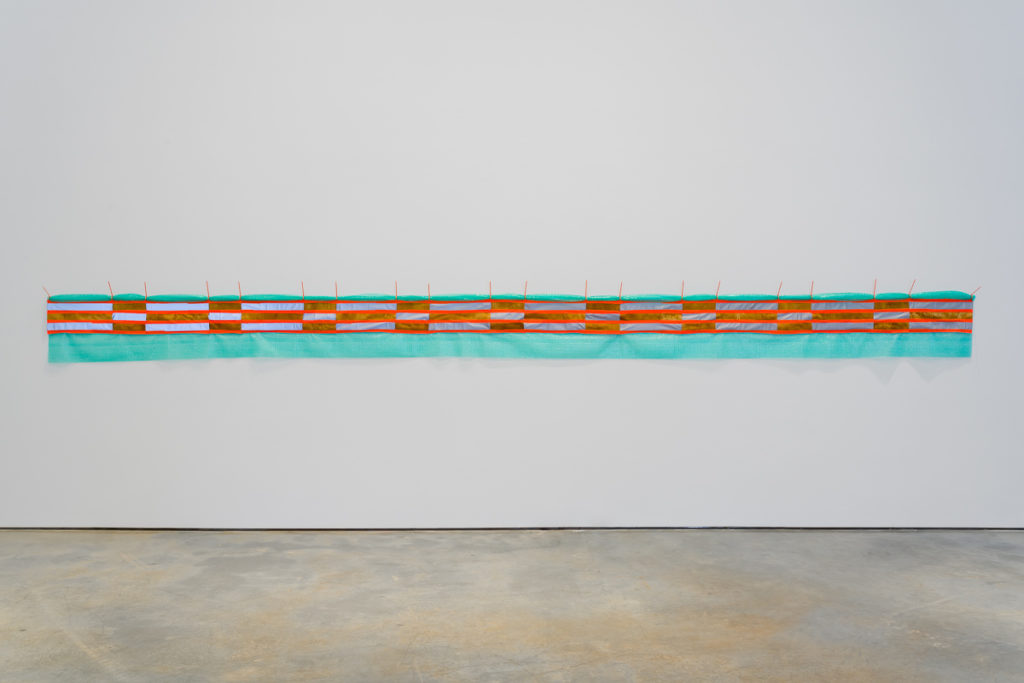

In Delta Trim (2018), Gruben translates a one-inch section of her mother’s delta trim pattern into a wall hanging of just over twenty-one feet in length. Delta trim is a form of applique used to adorn items of clothing from parkas to mittens and mukluks. Traditionally made with a variety of furs and skins, and more recently with fabric bias tape, the geometric designs that constitute delta trim patterns are the unique signatures of their makers. The pattern and skill are passed on through generations.

Gruben’s mother was a consummate seamstress, making all of the family’s clothing as well as regularly commissioned to make many pieces for her community, where she was well respected. Gruben grew up in Tuk at a time when there were no shops and all the family had was a dog team. Reflecting on the significance of her mother’s work, she says, “We never thought of it as art. It was the practicalities of day-to-day life.” Gruben’s mother would take apart cotton flour sacks for the thread, a repurposing born of necessity, which Gruben has clearly absorbed within her artistic practice.

Considering “the Native woman as craftsperson within a hierarchy of art,” Alutiiq artist Tanya Lukin Linklater discusses the way in which “functional art is practiced in the intimacy of one’s home, but also becomes a process of crafting for the public in a kind of performance of women’s work, of cultural work. Yet ‘craft’ is de-valued in the hierarchy of art.” Lukin Linklater addresses this devaluation through performance, where the gestures she performs—sorting beads or beading a headdress, for example—challenge the status of the “craft” object as commodity or artifact through the transitory nature of performance itself. Both Lukin Linklater and Gruben engage with “functional art” while also translating its utilitarian origins via conceptual, material and gestural means. The intimacy of the customary practices these artists engage in is also translated into public space, within art galleries and festivals, where the reception by and engagement of the public serves to multiply and complicate meaning.

Building on this idea, Métis art historian Sherry Farrell Racette characterizes the translation of customary practices into contemporary mediums as a form of continuity between past and present:

Traditional media, traditional form and the narrative power of objects constitute a critical linkage between contemporary and historic Indigenous arts. The merger of new and ancient media and practices is a deeply historic process through which generations of artists have physically manipulated materials and ideas from widely disparate sources into new forms.

She goes on to suggest that “artists draw from the meanings encoded in signs—reclaiming their knowledge, recounting histories, evoking emotion and stirring memory.” In its translation of her mother’s delta trim pattern through material means and a scaling up, Gruben’s work is at once intimate and monumental. Moose hide combined with blaze orange and reflective tape evokes the activity of hunting for either sport or subsistence. Materials made to be extra visible to the human eye (and invisible to the eyes of animals, in the case of the colour “blaze orange,” also known as “safety orange”) elicit a sense of warning or caution. The bubble wrap used in place of cloth for the material ground of Untitled (Delta Trim) formally contrasts the bright orange with its blue-green hue. For me, at least, the repetition of small plastic bubbles filled with air also paradoxically evokes the Arctic coastal tundra, laced with pools of water, or the cellular surface of pingos, the ice-cored hills that rise out of the permafrost near Tuk.

In utilizing and repurposing readily available materials to recreate one small section of her mother’s delta trim pattern as a large-scale wall piece, Gruben draws upon a visual and mnemonic lexicon constituted by the layered evocations encoded in the cultural and familial history of the form as well as those that arise from the artist’s chosen material combinations. Stitching My Landscape (2017), for example, is a monumental land-based work that similarly engages Gruben’s artistic and cultural matrilineage through a performative rather than object-based gesture. Farrell Racette argues that “artists who recreate encoded objects seek to repatriate their knowledge or bring their power to bear on critical contemporary situations.” Indeed, Delta Trim not only monumentalizes Gruben’s mother’s labour and knowledge but does so with a sense of urgency, presenting a disparate but purposeful cobbling together of materials that speaks of memory and the contemporary environmental and cultural realities of Inuvialuit life.

Inuvialuk artist Maureen Gruben graduated with a BFA in 2012 from the University of Victoria, where she was awarded the Elizabeth Valentine Prangnell Scholarship Award. She has since exhibited regularly across Canada and internationally. Her work is held in national and private collections. Prior to her BFA, Gruben studied at Kelowna Okanagan College of Fine Arts (Diploma in Fine Arts, 1990), the Enʼowkin Centre in Penticton (Diploma in Fine Arts and Creative Writing, 2000 and Certificate in Indigenous Political Development & Leadership, 2001). She has been recognized by Kelownaʼs En’owkin Centre with both their Eliza Jane Maracle Award (1998/99) and their Overall Achievement Award (1999/2000).

Originally published in the book Maureen Gruben: QULLIQ (Libby Leshgold Gallery and Emily Carr University Press, Vancouver, 2019).

References

Maureen Gruben, conversation with the author, October 27, 2018

Tanya Lukin Linklater, “‘Memory Is Embodied:’ Tanya Lukin-Linklater Interview,” interview by Thomas Michael Swensen, The Alaska Native Studies Blog, September 27, 2013.

Sherry Farrell Racette, “Encoded Knowledge: Memory and Objects in Contemporary Native Art,” in New Native Art Criticism: Manifestations, ed. Nancy Marie Mithlo (Santa Fe: Museum of Contemporary Native Art, 2012), 43.

Author

Tarah Hogue is a curator, cultural worker and writer based in unceded Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh territories/Vancouver, BC. She is a citizen of the Métis Nation with French Canadian and Dutch ancestries. As the inaugural Senior Curatorial Fellow, Indigenous Art at the Vancouver Art Gallery, Hogue has curated Ayumi Goto and Peter Morin: how do you carry the land? (2018), and co-curated Transits and Returns (2019), among other exhibitions. Her writing has appeared in BlackFlash, c magazine, Canadian Art, Inuit Art Quarterly, MICE Magazine and others. Hogue serves as co-chair of the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective/Collectif des commissaires autochtones.

Tarah Hogue is a curator, cultural worker and writer based in unceded Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh territories/Vancouver, BC. She is a citizen of the Métis Nation with French Canadian and Dutch ancestries. As the inaugural Senior Curatorial Fellow, Indigenous Art at the Vancouver Art Gallery, Hogue has curated Ayumi Goto and Peter Morin: how do you carry the land? (2018), and co-curated Transits and Returns (2019), among other exhibitions. Her writing has appeared in BlackFlash, c magazine, Canadian Art, Inuit Art Quarterly, MICE Magazine and others. Hogue serves as co-chair of the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective/Collectif des commissaires autochtones.