The intangible elements of heritage such as memories, traditions and skills often receive the least attention. We draw on our intangible heritage daily and often in very personal ways. The way we live is derived from traditions both consciously and unconsciously passed down. These traditions are fluid and mingle with modern circumstances and influences. This is why memory and tradition can be so easily lost—it naturally evolves and sometimes disappears before we notice. Nevertheless, in a perpetually changing world, it is important to find a place for those traditions that carry meaning even after the relevance of their original purpose fades.

Many of these traditions have been manifested in handmade items, like hand-woven rugs/embroidered shawls, folk art pieces, old utensils, jewellery, or even musical instruments which lent melody to songs offered to deities during important rituals.

As we advance technologically and innovate on processes, crafting techniques evolve and somewhere we lose memory of that which existed originally. In an effort to celebrate our past, and those small tokens of yesteryear’s culture, Handmade Tales seeks to archive Indian crafts from the pre 90’s era. We believe that to know your future, you must know your past.

The Archiving Project is intended to be an online repository of photographs and brief descriptions of traditional objects/crafts/textiles etc. which are representative of India’s intangible heritage and emerging culture. Through this online repository, we hope to give a voice to all those priceless memories and treasures which many families have kept safe, so the children of the new India can cherish their rich heritage for years to come.

Two examples from Handmade Tales Archive

1. Bidri Mir-e-farsh : [As told by Laila Tyabji, founder, Dastakar]

My mother came from the Hyderabad, the State of the Nizam, so we grew up with old bidri and I have always loved it. I have quite a number of 17th and 18th century hookah bases and ugaldaans (which I use as vases), and bowls, boxes and plates, but one of my favourite objects is this mir-e-farsh or “slave of the carpet”. They were used to hold down the light floor coverings on which people sat, or the chadars that covered Muslim graves, and they were shaped like miniature domes themselves. My parents owned a set of 4, and now my 3 brothers and I have one each! I find it absolutely charming, and particularly love the fact that the underside, which one wouldn’t really see when it was placed on the floor, as it was meant to be, is as beautifully ornamented as the upper portions. This one quite small object (it’s about 6 inches high) has EIGHT different designs, but each melds so perfectly with the other, it doesn’t look over-ornamented or discordant.

Bidri is what was known as gunmetal (an alloy of zinc and copper) blackened to give it its characteristic patina, and inlaid with silver sheets or wires in decorative floral or geometric patterns. Indian bidri originated in Bidar, (thus getting its name) in the time of the Bahamani Sultanate, where craftspeople were taught the skill by an emigre Iranian master craftsman. It was loved and patronised by successive Nizams. It’s not so popular today, perhaps because it’s quite difficult to maintain: if you use silver polish there’s a danger the black patina will fade, and if you don’t clean it the silver blackens and tarnishes. Those of us in the know use coconut oil and finely ground coal ash. The designs too have lost their earlier delicate yet dramatic panache.

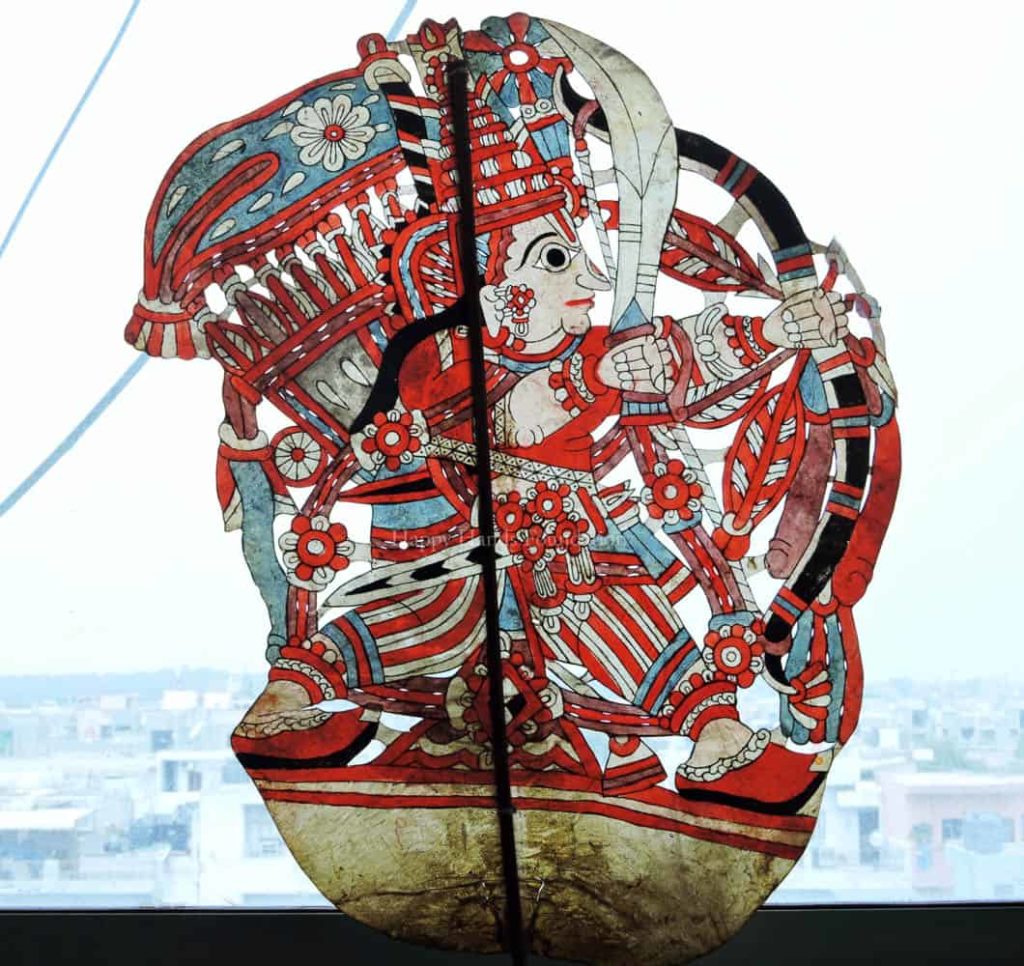

2. Leather puppet by Gunduraju (Artist)

The leather puppet by artist Gunduraju is at least 300 years old. In conversation with him, one realises how important this one piece is—it has been handed down to every generation of puppeteers once the “learning has been complete”. The puppet of Arjuna is passed on signifying the excellent Guru-Shishya relationship as emphasised in the Mahabharata. It’s a reminder to the artist that they must uphold the values of excellence in the art at all times.

To Gunduraju, this puppet is representative of his arduous training, which he claims was 30 years long! He first learnt how to sing the songs, and learnt them by heart. Then worked on his voice modulation and expression in singing. And finally, learnt how to manipulate the puppet.

This puppet, Gunduraju explains, was created using deerskin. The colours and ink used ages ago are not available today, even the knowledge of how to make those colours has been lost. This one puppet is in two colours mostly, though with the evolution of the art, more colours were introduced. Still today, bamboo pens are used for the black outline of each puppet, but instead of charcoal-lamp-substance, they dip it in black watercolour inks. Today, the puppets are smaller than they used to be.

Gunduraju frankly admits that his son wasn’t keen on puppetry and so this puppet would be handed over to his son-in-law Madhu who he has chosen to train and develop.

On being probed whether he thinks this puppet should be in a museum, he responds with a vehement “No!” Many of his family members had sold their ancestral puppets in the hope that they would be preserved better, but today they don’t even know where they are.

From the development perspective: aims of the Storytellers Collective

This project has a twofold focus: to revive the storytelling traditions of India by introducing them as an important educational-tool and to provide a platform for young adults to work together to impact their own communities. The Storytellers Collective is a community-arts program in New Delhi, which involves:

- recruiting and training 10 Youth Educators from colleges / universities through an in-depth apprenticeship training under Master Artisans

- the development of an 8-month curriculum based on traditional storytelling which would be implemented across various shelter homes, community school centres for at-risk children and youth (Students)

- and building a repertoire of visual narratives which have a social or cultural relevance to the communities to which the students belong and those which can be developed into effective educational aids.

Through this project, we not only revive the storytelling aspect of the art form, but also work closely with artists to develop new narratives. The Storytellers Collective was thus conceived as an extension of Happy Hands Foundation’s commitment to revive India’s heritage through the technique of traditional storytelling as a tool for education and engaged learning.

Today we have 120 young patua practitioners, and this year 150 students have enrolled to learn the art of Cheriyal scroll making.

One example of how it was applied with children

In 2015-16, we focused on patua art of West Bengal. Patua is a narrative art form, traditionally painted on scrolls which can be as long as 10 feet. The scrolls were used to narrate folk stories in communities by the artisans who would travel from one village to another. The narration of a patua story is usually in the form of a song, which the artists sing along as they unfold the scroll.

Youth Educators underwent a ten day apprenticeship training under the guidance of Master Artists Rupsona Chitrakar and Sumon Chitrakar. They even learnt how to compose songs to accompany the scroll, and about the various tunes that exist. We also learnt that each emotion depicted in the art form is represented by a specific tune. A tragic story’s tune differs from that of a comic story.

Educators then formulated a structured curriculum to be implemented with young children over a year. The curriculum was designed in such a way that so the children learn how to build stories and create a visual narrative. It began with children learning small elements of the art form such as borders, different facial expressions, body outlines for male and female figures, etc. In teaching children the art form, our team also developed worksheets and instruction manuals which could be used by art-teachers. A sample is given below (attachment).

The technique of storyboarding helped children break down their narratives into visuals and finally what they created resulted in a series of stories and songs.

As part of Folk Fables, our annual exhibit, we showcased original art works along with story-prints, and had the children perform their narratives to an audience. This provided immense encouragement to the young participants.

A lot of children from our batch of the first 100 have continued to practice the art even though the teaching period has ended. They practice by making daily life scenes, or illustrating their history chapters in patua form. For the artists, they learnt how to develop new narratives and break them down. For all of us, the entire process of working with such creative individuals and bringing them together was a huge learning experience.

This year our focus is on the ancient storytelling art of Cheriyal Scroll Paintings, which originated in Andhra Pradesh and today only two families know and practice the art.

Future challenges

A huge challenge that exists is the use of natural materials in the teaching process. Patua art, for instance, uses flower-based powder colours and an old cotton cloth to bind the paper-scroll with home-made glue. All of this makes the process complete. However, working in urban under-resourced schools, we can hardly teach using the same techniques. Shadow puppetry for one, is a module we are planning for next year, but a big hurdle is providing the right tools to the students to cut, pierce holes, etc and sourcing the actual goat-skin leather used for puppet-making.

Another challenge is the transfer of original songs and story education. For instance patua scrolls are sung in Bengali. So it became very difficult to transfer the skill of composing songs in a different language.

The third challenge we faced was on building teaching capacity of artists. It has been quite challenging to share educator-skills with artists who till now have only created and aren’t very comfortable with articulating the process or breaking it down.

A different way of looking at this as a future challenge would be the recognition of young talent and the association with the original artists. There are many young generation artists who practice narrative arts. Would developing more young artists in urban centres in any way be a threat to existing children of artisans in villages? These young children, who we teach, have no connection to the history or tradition of the art. How they experiment with this new form they learn might impact the audience’s understanding of the traditional art.

While it is important that the new generation indulges in creating new content for story-scrolls, it is an absolutely important part of our project to build a repertoire of old, and traditional narratives, not just as reference points, but also to trace the emergence of creative skill. Those who have not engaged with the art earlier, would definitely come up with newer elements and their own renditions of the art, but at the same time, it would be our endeavour to showcase traditional work to the audience so they can see for themselves how art changes with time.

Author

Medhavi Gandhi is a cultural practitioner based in Chandigarh, India. She is the founder of the New Delhi-based nonprofit, Happy Hands Foundation and is committed to the cause to reviving folk arts, crafts and narrative traditions of India. She is currently working on connecting citizens with the Museum sector in India through The Heritage Lab project, a result of her love for stories and the hunger to learn about heritage.

Medhavi Gandhi is a cultural practitioner based in Chandigarh, India. She is the founder of the New Delhi-based nonprofit, Happy Hands Foundation and is committed to the cause to reviving folk arts, crafts and narrative traditions of India. She is currently working on connecting citizens with the Museum sector in India through The Heritage Lab project, a result of her love for stories and the hunger to learn about heritage.