- Winnie Pelz, 1979, photo by Grant Hancock

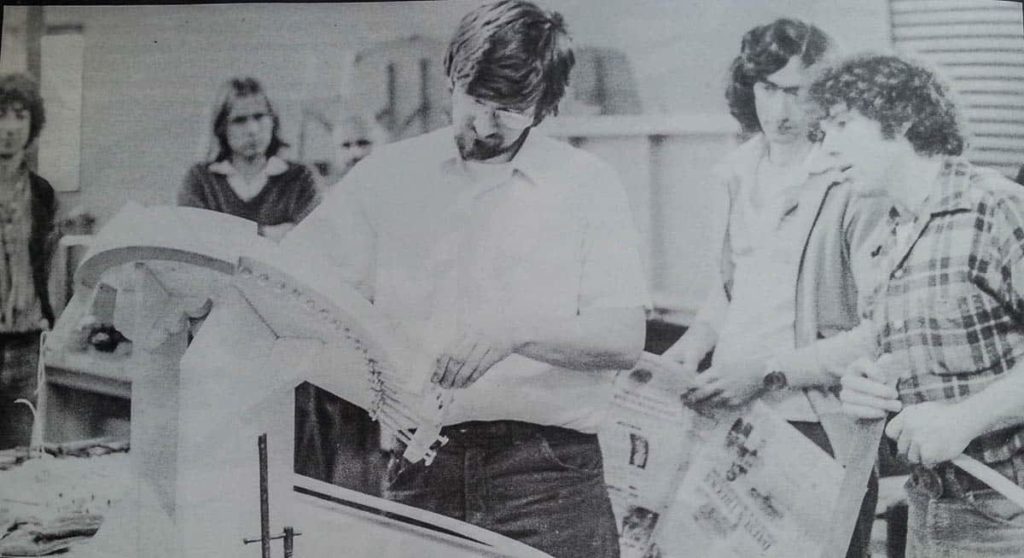

- Late 1970s, leather trainees, courtesy JamFactory

- Rob Knottenbelt, 1977, photo by Grant Hancock

- JamFactory Gallery, 1976, photo by Grant Hancock

- Ceramics workshop, 1979, photo by Grant Hancock

- Gallery Paynehem Road, 1976, courtesy JamFactory

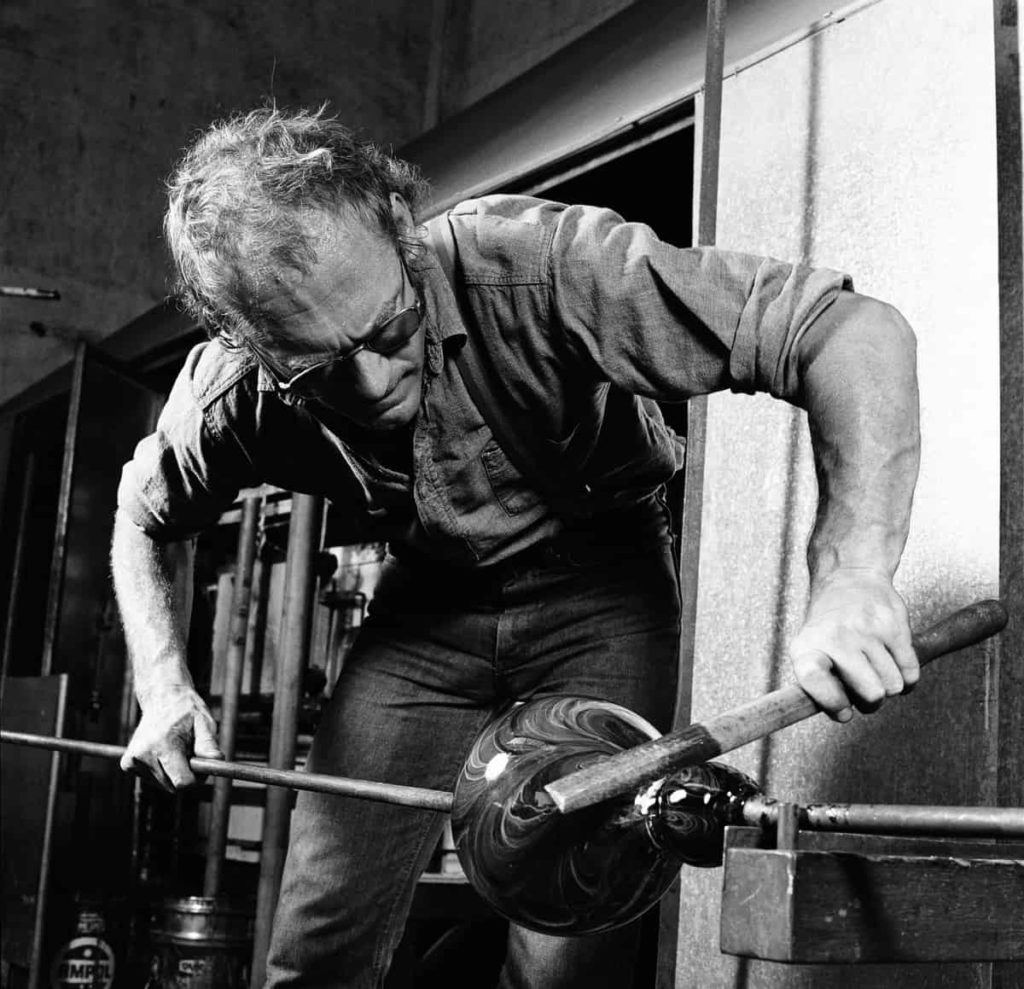

- Rob Knottenbelt, 1977, photo by Grant Hancock

- 1978: Craft Association of South Australia Craft Fair at Elder Park in conjunction with the Adelaide Festival. Photograph: Grant Hancock. In the 1970s and 80s The Craft Association of South Australia (as we were known then!) held Craft Fairs at Elder Park in conjunction with the Adelaide Festival. It’s estimated that this one in 1978 was attended by 100,00 people with approximately $60,000 of craft being sold. Impressive. Photo: Grant Hancock

- Guildhouse Wooden Boat Exchange, Chris De Rosa and James Edwards at Armfield Slip, 2012. Photograph: Grant Hancock

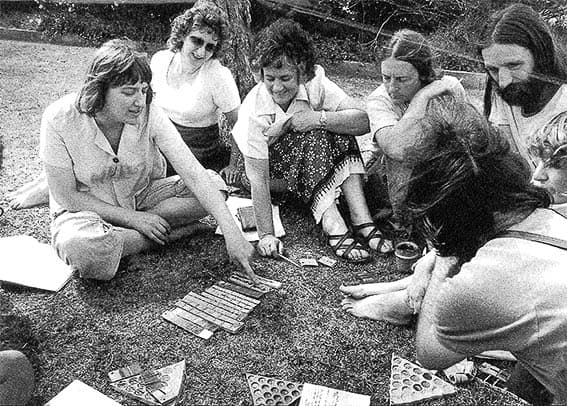

- 1979 Crafts Council visiting fellow Michael Cooper hosts a 2 day workshop with participants including then Crafts Council of South Australia President Jeff Mincham.

- Tatachilla Summer School (late 1970s). Photograph: Grant Hancock

- 1989, Guildhouse Makers’ Choice artists L – R Bruce Nuske, Catherine Truman, Kay Lawrence

- Tom Moore Studio Session, 2014. Photograph: Ben McPherson

- Guildhouse at Art Shanghai, 2014. Photograph David Campbell

One of the apparent truisms of the contemporary moment is that place no longer matters. That digital technology means that those of us with the material and cultural abilities to do so, can transcend the tyrannies of distance: communicating seamlessly with people around the world; accessing information from beyond once narrow skill-sets and communities of knowledge; globally sourcing niche products; and, in turn, setting ourselves up as global exporters operating out of our home office, studio or kitchen table.

Certainly this changed digital environment provides new possibilities for sustainable creative micro-enterprise, including in high profile ways given the wider public awareness of websites such as Etsy – ‘the eBay for the handmade’ – and growth of less high profile but more curated and specialist retail options often run by design/craft organisations themselves such as here in South Australia Guildhouse’s recently launched wellmade website.

However as many makers well know, the ease of establishing online shopfronts and a professional identity hides the complex work required to start and run a small business, especially one in an increasingly globally competitive space with isolated producers, narrow profit margins and downward price pressure from many online sellers. This raises new challenges for craftspeople who not only require practice-based skills, but new entrepreneurial skill-sets—both technical and personal—to operate successfully as a micro-enterprise in this emerging global market. Pursuing a creative career has long been seen as a precarious path to walk; a situation exacerbated by the absence of clear-cut career pathways post-graduation, and this situation has been even further in Australia by the winding back of grant funding such as the ArtStart program which gave many local craftspeople their professional leg up.

So a creative micro-economy that emphasises ‘long tail’ buying ‘directly’ from the maker offers both creative graduates and more established designer-makers micro-entrepreneurial pathways not previously open to them. But to maximise the potential of these opportunities at a practical level, skills in professional practice need to be complemented by other capacities. Including today the skills to successfully negotiate the use (but not over-use) of social media as a marketing tool requiring the promotion of producer self-identity as part of the value being sold.

Therefore, to (among other things) identify what kinds of education and training, especially around the transition from higher education to self-employment, are required in the sector; better inform policy discussions around the risks associated with embarking upon such an entrepreneurial course, and the need for greater support if governments around the world wish to see this sector and business model grow; and provide an evidence base for the value of investing in makers through programs such as ArtStart, NEIS as well as more traditional travel and exhibition funding, the 3 year Australian Research Council funded project Crafting Self is meeting with craft practitioners and key organisations around Australia to follow their stories. We are particularly keen to hear from recent graduates and/or those just starting their professional practice so that we may chart your journey during this important establishment period and the first couple of years of your practice.

To return to the issue of place, one of the many cases that must be made when applying for Australian Research Council (ARC) funding is to convince your peers that this research is best done by a particular team, and thus out of a particular university or cross-institutional collaboration. While prima facie Adelaide is not a likely place from which to undertake a national study, the case for ‘why South Australia?’ in the context of craft was an easy one to make. South Australian design craft punches above its weight, and while many factors feed into this reality, a key driver is the leading role played over the last 40-plus years by the JamFactory. Recognised nationally and internationally as a centre for excellence, for 40 years the JamFactory (now located next door to the University of South Australia’s City West campus which includes its School of Art, Architecture and Design incorporating the South Australian School of Art (SASA) established in 1856.) has supported and promoted outstanding design and craftsmanship through its widely acclaimed studios, galleries and shops.

Much has been written in this issue and elsewhere on this icon and there is not space to do justice to this here, but it is valuable to note the historical parallels between contemporary governmental hopes for design and craft making as the future of employment growth in the face of a downturn in traditional manufacturing, and as one of the major drivers behind the Jam’s establishment in the 1970s. The formation of the JamFactory at its former site in suburban Stepney was a result of lobbying by the politically savvy crafts community and key political advocates, amongst them Premier Don Dunstan, who inspired by William Morris saw craft and design as drivers of local production. The establishment of the JamFactory is reflective of a wider and enduring recognition by the South Australian government of the cultural and economic contribution made by small creative producers.

Place does matter; just as key people and institutions matter to place. Place matters when it comes to materials, including unique and inspirational raw material, and access to skills and supply chains. Place remains a source too of inspiration for makers, even in urban settings. It also matters when accessing markets – just ask a Tasmanian maker about transporting their work over the ‘the most expensive stretch of water for shipping in the world’ (Bass Strait). From our early research findings it is clear place and people’s connection to it also influences craft sales. Despite the essential role of social media, online marketing and website development to their business, place matters to makers; face to face exchanges between maker and client is still how most sales income is generated. Paralleling the growth of, and often in tandem with, artisanal food practices, we’re also seeing the rise of local markets where buyers meet makers and growers and hence form a connection with the market. Different to the twee craft weekend craft markets of the past and part of a larger lifestyle shift, such local markets seem to be an antidote to the rise of on-line shops. The object made by hand is also, ironically, still largely bought from the physical hand of the maker, with subsequent communication and sales then often facilitated by the virtual world of the internet.

Place also matters to us as researchers based in Adelaide. We are conscious that many studies can overlook Australia beyond the eastern seaboard, so we are keen to keep meeting makers operating in all sorts of geographic locations with the challenges and opportunities these give rise to (despite the ‘death of distance).

Thank you to all those inspirational makers across all levels of career we have already spoken to, and please do get in touch with us if you wish to find out more about the project and to get involved.

Project Team: Susan Luckman, Jane Andrew, Belinda Powles

Project Website: http://www.unisa.edu.au/craftingself

Email: crafting_self@unisa.edu.au

Author

Susan Luckman is Professor: Cultural Studies in the School of Communication, International Studies and Languages and Associate Director: Research and Programs of the Hawke EU Centre for Mobilities, Migrations and Cultural Transformations at the University of South Australia. She is currently Chief Investigator on a 3 year Australian Research Council Discovery Project ‘Promoting the Making Self in the Creative Micro-economy’ which explores how online distribution is changing the environment for operating a design craft micro-enterprise. She is the author of Craft and the Creative Economy (Palgrave Macmillan 2015), and Locating Cultural Work: The Politics and Poetics of Rural, Regional and Remote Creativity (Palgrave Macmillan 2012), as well as being a ‘jack of all trades, master of none’ as a craft maker.

Susan Luckman is Professor: Cultural Studies in the School of Communication, International Studies and Languages and Associate Director: Research and Programs of the Hawke EU Centre for Mobilities, Migrations and Cultural Transformations at the University of South Australia. She is currently Chief Investigator on a 3 year Australian Research Council Discovery Project ‘Promoting the Making Self in the Creative Micro-economy’ which explores how online distribution is changing the environment for operating a design craft micro-enterprise. She is the author of Craft and the Creative Economy (Palgrave Macmillan 2015), and Locating Cultural Work: The Politics and Poetics of Rural, Regional and Remote Creativity (Palgrave Macmillan 2012), as well as being a ‘jack of all trades, master of none’ as a craft maker.