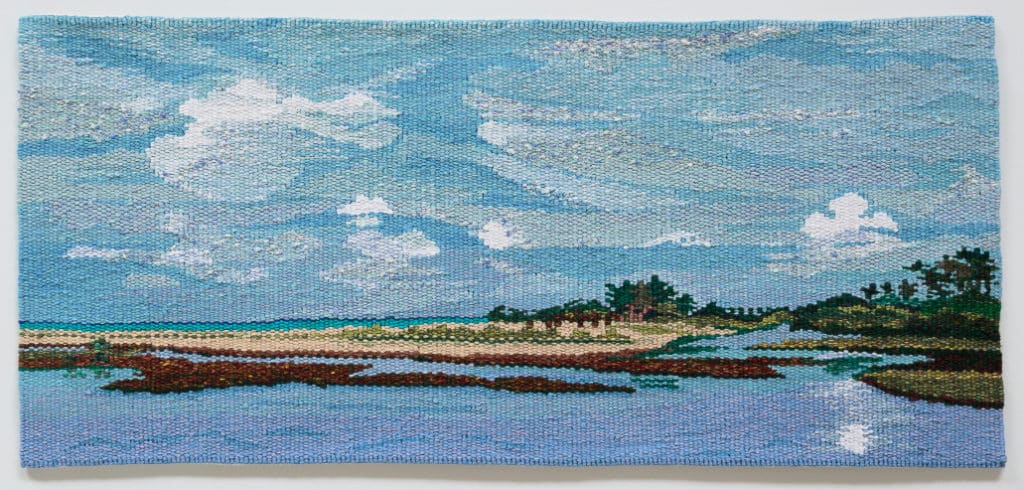

Cresside Collette, The Western Monasteries – Anuradhapura 1, 2017, woven tapestry, 9 x 58 cm; photo: Tim Gresham

The idea of the postcard has always appealed to me. A little pictorial piece of the country one is travelling in makes its way back home to friends and loved ones bearing a small glimpse into the world you are inhabiting, usually for a short period of time, offering a taste of your experience that gives as much pleasure in the writing as in the receiving. Of course, I am old enough to have written many such physical postcards in my time and did so when I first started travelling back to the place of my birth, Sri Lanka, or Ceylon as it was then, in 2009.

After a couple of years, I devised digital postcards that I sent via email, featuring a string of eight or so images with commentary attached, in which I could write in more detail about the places I was visiting and from which I could elicit a more immediate response that was much more satisfying. So when I was offered an exhibition of my tapestries in Colombo’s best, most professionally run gallery, I knew exactly what the format would be: small, intense observations of landscape true to my vision of the country that formed my childhood and my way of being in the world.

Here’s a statement I wrote for the show I had at the Saskia Fernando Gallery in Colombo, Sri Lanka earlier this year.

Why is it that our earliest influences remain so potent in our lives? Everything that touches our senses as young children remains an indelible part of us, whether we choose to put it to one side during our evolution into adulthood or not.

Every time I return to the country of my birth, my senses are awakened to that familiarity, no longer foreign but an essential part of my being. I smell the ripe pungent air on arrival. The warmth envelops me in its stifling embrace. I hear the accents that surround me and I slip into the sing song easily, tailoring my own speech patterns to identify with them. The tastes have never left me. In 55 years, my own culinary practice pays homage to the spices and techniques that bind me to this island. All that I see is imprinted on my psyche as I hungrily seek out the visual treasure that informs my art practice.

And so where is “home” really? Those of us who have lived our lives separated from our birthplace dwell in limbo, longing to belong. I can feel Australian in many aspects of my life but not completely. I was planted in a different soil, grew and reached for the sun in a different climate, absorbed the culture and manners of a different society as I grew. It will always be part of me, and yet is lost to me as the country I knew as a child has evolved into something other.

Home is what you imagine it to be, make it to be. My hands shape it into existence through the one constant that cannot be changed, the natural environment that speaks to the heart.

It was February, Valentine’s Day, that the exhibition opened, an auspicious symbol of the love I have for my homeland seen through the eyes of someone who grew up in Australia conscious of the benefits that this lucky country can bestow on those given the chance to attain citizenship and flourish in its benign light.

In February this year, the world seemed to be Sri Lanka’s oyster, it was Lonely Planet’s number one tourist destination; it was buzzing with happiness and goodwill. No one would have guessed that its heart would be ripped out, once again, in the wake of the meticulously organised and executed Easter Sunday bombings. Recovering from a twenty-five year civil war and the devastation of the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami the country has suffered blow after blow and yet its human spirit rises to shine with all that is generous and hopeful.

These tapestries were made in a time of peace when my hopes for my country were high and I could reflect on its beauty and variety. I started to go back to Sri Lanka in November 2009, six months after the bloody civil war had officially ended. The streets were full of military carrying machine guns and checkpoints were frequent where identity papers had to be produced. When I returned in 2010, the superfluous army had been turned into police, and a more relaxed attitude started to permeate the place. I have been back almost every year since, watching the country unfold its petals of freedom and flower as it regained its confidence and offered its beauty to the world.

And now this hideous setback.

In 2009 I was fortunate to meet writers, artists and academics at a conference organised by Ayesha Abdur-Rahman for Lanka Decorative Arts. I was invited back in 2010 to speak about my own art practice and then taken by historian SinhaRaja Tammita-Delgoda on field trips to some of the most visually sublime locations where I commenced a series of drawings. In 2011 I returned for seven weeks to weave small tapestries en plein air in these and other locations. These included Kalpitiya, a north Western spit of land flanked by sea and lagoon, a lush private garden near Weligama, a strip of view through a window in the hills of Digana, and the expansive Brief garden, created and nurtured in the Bentota hinterland by an old friend of my parents, Bevis Bawa. The drawings and tapestries formed the basis of all the works in the exhibition, drawn directly from acute, first-hand observation and immersive experience.

Other places such as the Kaludiya Pokuna sing in my memory. It is an enchanted world where a monastery once stood by a deep pool of black water, encased and protected by hills and forest. Once when I was there, some young monks appeared, stripped off their saffron and dived into the water, splashing like schoolboys, echoing the ancient past when this would have been a daily ritual. And the expansive ruins of Anuradhapura, remnants of monasteries and palaces and dagobas, old as the pyramids of Egypt, dotted through 16 square miles of irrigated land that speak so eloquently of a vibrant civilisation.

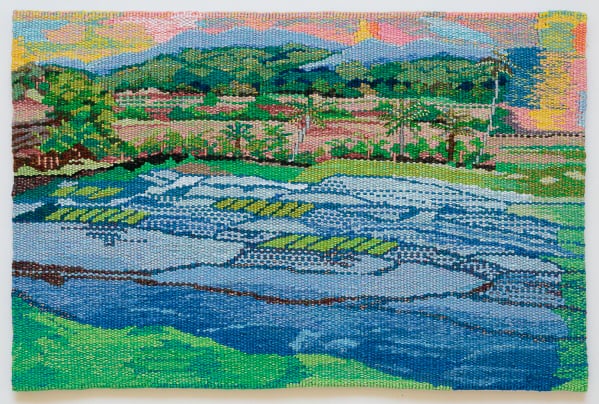

Further travels encompassed the southern wildlife park of Yala, where the bone-rattling jeep ride at dawn produced no sightings of leopards but yielded a panorama of wetlands gorged with waterlilies. And throughout the country the ubiquitous paddy fields, a source of nourishment to its inhabitants, in an island where starvation is unknown.

Cresside Collette, Paddies near Hanguranketha, 2018, woven tapestry, 33.5 x 50 cm; photo: Tim Gresham

These are the resonant images of what this land has offered me in return for my frequent re-visits. When I was a child living in Colombo in the 1950s I was never taken to see these sites, so I have relished the opportunity to get to know them as an adult and pay homage to them in my work. The exhibition, for me, was the closing of the circle of my life, the all-important chance to go back and illustrate the connection that I have to the place I was born and grew up in. And despite the violent setback that Sri Lanka suffered this year I will respect the continuum and engage with the country and its people in the years to come.

Author

Cresside Collette is a tapestry artist and has been a weaver for 43 years. She originally trained for and became a foundation weaver of the Victorian Tapestry Workshop (now the Australian Tapestry Workshop) in 1976. She has been an exhibiting artist since 1971 and taught tapestry weaving and drawing at RMIT University for 11 years. Since 2011 she has established an annual tour to France and the UK to view the best of historical tapestry and engage with contemporary practitioners of this craft.

Cresside Collette is a tapestry artist and has been a weaver for 43 years. She originally trained for and became a foundation weaver of the Victorian Tapestry Workshop (now the Australian Tapestry Workshop) in 1976. She has been an exhibiting artist since 1971 and taught tapestry weaving and drawing at RMIT University for 11 years. Since 2011 she has established an annual tour to France and the UK to view the best of historical tapestry and engage with contemporary practitioners of this craft.

Comments

Wonderful artworks. Fascinating authorship too