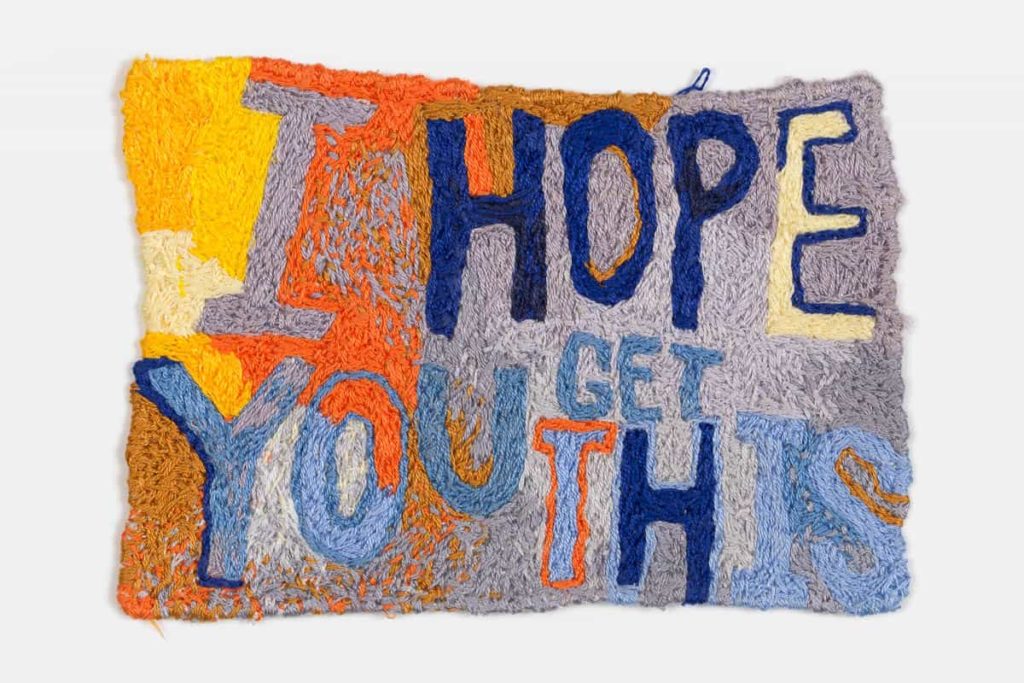

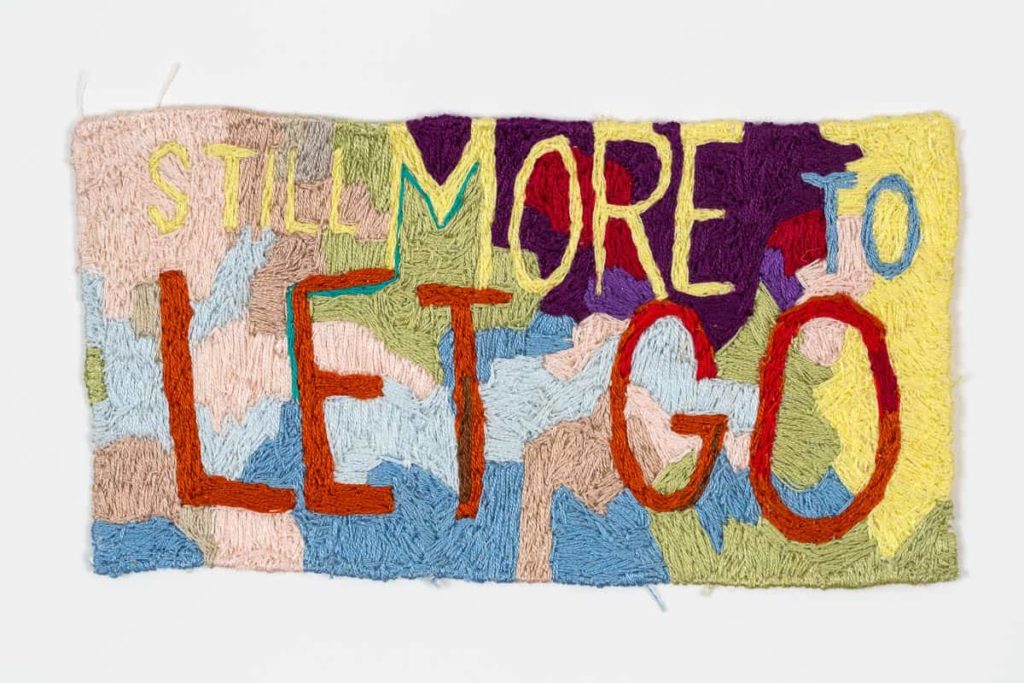

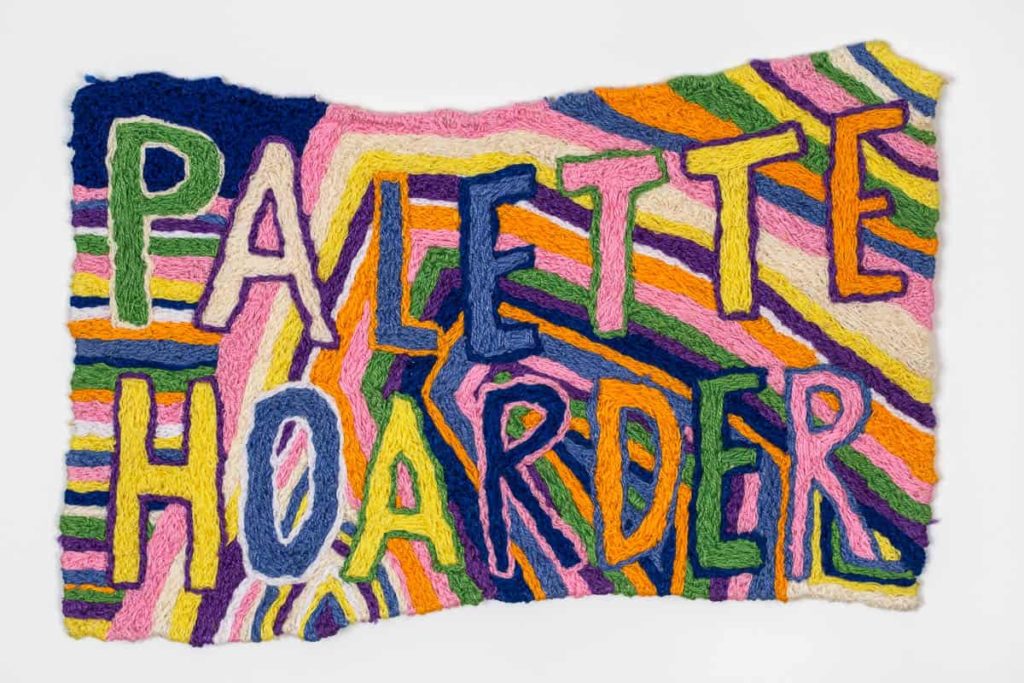

- Raquel Ormella, All these small intensities (detail), 2017, silk and cotton embroidery thread on linen, courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane © the artist. Photo: David Patterson.

- Raquel Ormella, All these small intensities (detail), 2017, silk and cotton embroidery thread on linen, courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane © the artist. Photo: David Patterson.

- Raquel Ormella, Wealth for toil I, 2014, synthetic polymer paint, hessian, metallic thread and ribbon 220 x 270 cm Courtesy Milani Gallery, Brisbane © the artist

- Raquel Ormella, Wealth for toil I (detail), 2014, synthetic polymer paint, hessian, metallic thread and ribbon, 220 x 270 cm, Courtesy Milani Gallery, Brisbane © the artist

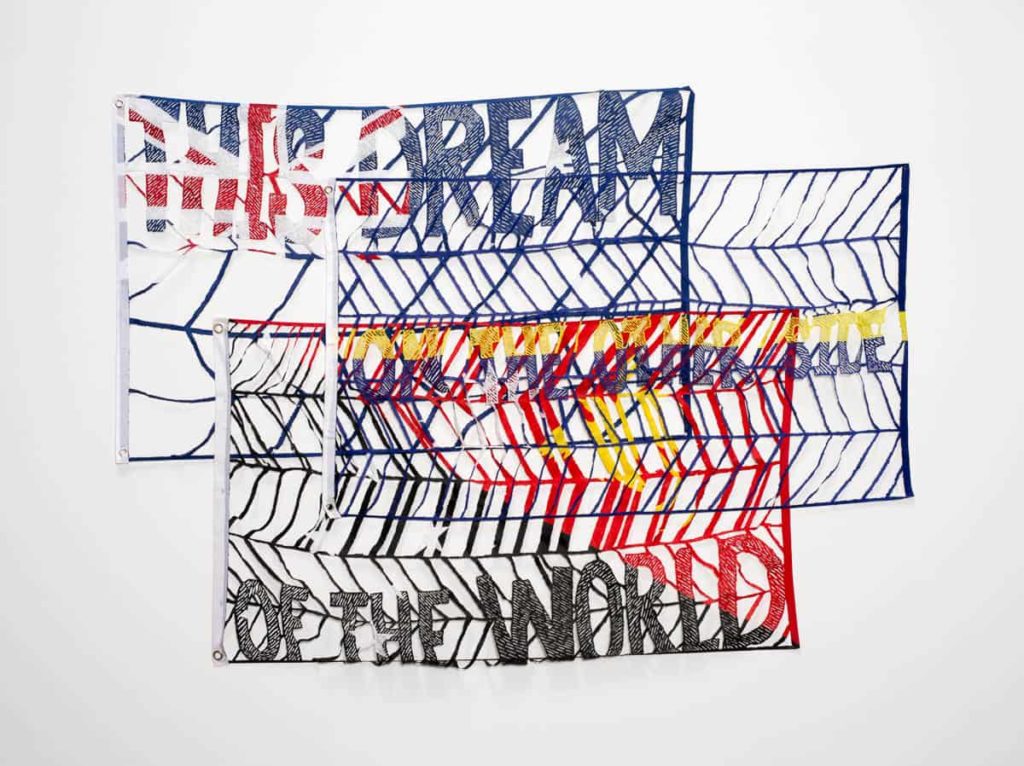

- Raquel Ormella, This Dream, 2013 nylon 150 x 210cm Collection Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney © and courtesy the artist

- Raquel Ormella, This Dream, 2013 nylon 150 x 210cm Collection Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney © and courtesy the artist

- Raquel Ormella, All these small intensities, (detail), 2017, silk and cotton embroidery thread on linen 8 x 13cm irreg. courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane © the artist Photo: David Patterson.

- Raquel Ormella, All these small intensities, (detail), 2017, silk and cotton embroidery thread on linen 8 x 13cm irreg. courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane © the artist Photo: David Patterson.

As Raquel Ormella started to prepare for her major survey show at Shepparton Art Museum (SAM) and its subsequent national tour, small intimate tapestries began to appear on the artist’s social media platform of preference, Instagram. These images of new embroideries and skeins of coloured threads for embroidery palettes were accompanied by a series of biographical commentaries and hashtags about hoarding and unfinished objects (or UFO’s as they are called by some people I know with similar habits). I was in Shepparton, Ormella in New South Wales; but Instagram shared the intimate and the professional with instantaneous visuals. For an artist working in the traditional materials of fabric and thread, how did 21st-century Instagram modify and mediate the artist’s voice?

Instagram seems to be designed for those who work with images. A pithy hashtag or smart one-liner is usually all that’s needed to complete the story a picture tells. Numerous artists and arts professionals have leapt onto the medium. Many have merged personal and public personae, with varying degrees of privacy or veracity. Raquel Ormella and other artist colleagues in Australia and overseas have all made the medium their own. It makes the world seem smaller, our community more global and our idiosyncratic hobbies more rational as we link with a subset of like-minded others sharing interests in a particular visual meme, the experience carefully curated, not by human hands but by an ever more subtle software algorithm that reflects our desires back to us. For the artist and art professional, while the approach may look casual, the successful site is as carefully curated as any other big-ticket show. As much, if not more, rests on the follow, with an audience that is immediate and global in its reach.

There are, of course, pitfalls for those not born with a screen or device in their hands. At a recent international conference, one of my curator friends described the current state of curating as #itscomplicated. There’s a growth in Instagrammable artwork, which can appear so much better on the screen than in the flesh. A social media frenzy surrounded many of the artworks in the National Gallery of Victoria’s epic NGV triennial 2018, perhaps presented precisely to encourage such a reaction. And while artist and activist Ai Weiwei’s most recent giant inflatable, Law of the journey 2017, was billed as the showstopper of Mami Kataoka’s Biennale of Sydney 2018, millions had already seen images of the artwork in its previous presentation at the National Gallery, Prague, in 2017, circulated widely around the world on social media.

Ormella has long been interested in how communities work, actively participating in grassroots organisations. Often, there is a social or political agenda, with a strongly personal connection, though Ormella has in the past been cautious about these works only being read through this prism (See, for example, Lizzie Muller, “An interview with Raquel Ormella”, in Raquel Ormella: she went that way, exh cat, ed Reuben Keehan, Artspace Visual Arts Centre, Sydney, 2010, p 32.) The SAM exhibition revisits early seminal works presented alongside more recent works for the first time. Wild Rivers: Cairns, Brisbane (2008), four whiteboards covered in Texta marker drawings, and their associated works on paper, both combine meticulous line drawings detailing networks, connections, workings and natural beauty. Documenting the Wilderness Society’s lengthy campaign to protect a number of Queensland river basins from land development, mining and irrigation, through the state’s Wild Rivers Act, Ormella presents these on the office-aesthetics of now redundant whiteboard technology. Some are in colour, and some in a grisaille of green line drawing on white ground. Other early works featured include Ormella’s Banner works, which refer to political activism, and the desire to find a personal voice within it. The text in many of Ormella’s banner works alludes to biographical aspects of the artist’s own life as well as national events and political utterances. The very title of this exhibition, I hope you get this, reveals Ormella’s hope that her own artist’s voice is heard in the exhibition and provokes her audience to action.

Ormella has long used fabrics and other textiles to create large sculptural paintings and wall works. For Ormella, whether stitched by hand or machine, her materials have the patina of their original purpose, such as the dark blue of Kingees workwear favoured by blue-collar workers, including her own father, or the high visibility reflective fabrics that the mining boom turned into airport-wear. Ormella’s textile and fabric paintings regular reconfigure our understanding of national tropes and cultural icons: from the deconstructed and rethought Australian flags in materials rich and poor, to the high-vis workwear that becomes the mapping of Antarctic national territories on the ever-shrinking ice. There are always two sides to a story, and the artwork is always infused with the environmental and social effects that accompany this economic activity: from the landscape damage of mining to the social dislocation and family stress of a “fly in, fly out” generation of workers on 20-day rosters.

Ormella’s choice to work in fabrics and thread, two traditionally female materials, has some roots in Rozsika Parker’s influential book, The subversive stitch, 1984 (Rozsika Parker, The subversive stitch: embroidery and the making of the feminine, IB Tauris, London, New York, 2010. Ormella also cites political theorist Jane Bennett’s book Vibrant matter: a political ecology of things, 2010, as central to her work, in which the author argues that a ‘vital materiality’ runs through and across bodies, both human and nonhuman.) For Ormella, it remains a seminal text and she cites it as playing a significant role in her rethinking of the gendered nature of art-making, materialities and labour. Parker notes that embroidery only became a purely female activity in the early modern world. Both men and women worked in the guilds and workshops of the Middle Ages. And needlework has always had class-based overtones: whether for goods produced for the rich, given the cost of the materials and hours of labour—however cheap; handwork for those who could afford the leisure time; or skills re-appropriated to create banners of solidarity early in the labour movement.

The series of small tapestries that Ormella has presented for the first time at SAM are all deeply personal, as their titles intimate: I hope you get this, Feminist politics, All these small intensities, Contemporary embroidery, Drawing with thread, Grunge ethics. Ormella divides them into three distinct periods. The first relates to her childhood, when Ormella was keen on “craft projects”, picking up skills either by osmosis or from her mother (who was keen, however, that she pursue a professional job that didn’t rely on manual skills). The second reflects her time at art school in the 1990s, when she used tapestry and embroidery stitching as a form of anti-painting. And the third corresponds to the 2000s when, as she notes, “I became a bit of a hoarder” (The artist in conversation with the author, 20 March 2018). Nothing from the first period of childhood craft activities has seen the light of day, save the photographs of her doll’s house furniture now shared on Instagram.

Grunge colour attitude ethics is a work from Ormella’s second phase of work with embroidery threads. Made from coloured threads remaining from the art school 1990s, Ormella uses what she describes as a “dark and drab” palette of browns, greys and some blue—the colour of her father’s work clothes. Alternating with these intimate-scaled objects presented front and verso in her Instagram feed of this work in progress are photographs of original Coats & Clark embroidery skeins bought during this art school period.

Ormella describes the third phase of her embroidery making and collecting as one of acquisition and hoarding. She presents on Instagram a recent embroidery made from threads acquired from this time. Presented as two images, the one above reads “PEAK LOSS”, the one below, “PEAK ACQUISITION”. Each palette carries its own history. The collision may reflect how people started giving Ormella their own precious things, once they knew she was reviewing and reworking her own collections and hoards. A vintage collection of threads, complete with original cardboard box labelled Wonderwear Hosiery, attracts the hashtags #foundpalette and #lettingthingsgo. So precious was its connection to the box’s original owner that the owner’s granddaughter held on to it for 20 years before handing it over to Ormella.

The recent series of tapestries are part of the Shepparton Art Museum exhibition and tour draw together many of these threads of Ormella’s life and work. They reflect on the histories of Ormella’s life, her materials and the very process of making. Now enjoying the process of stitching as relaxation as much as for its artistic content, Ormella frequently seems unwilling to let the works finish. In Ormella’s Instagram feed, the artist’s hand is often present, as is her material, an extension, if you like, of the artist’s voice of the past. Skeins of thread are held between thumb and forefinger in front of the work in progress, which rests on the artist’s knee—often clothed in a similar colour or complementary pattern. This is colour swatching on steroids, and certainly not to be missed in the flesh.

Author

Dr Rebecca Coates is a curator, writer, lecturer and Director of Shepparton Art Museum since 2015.

Dr Rebecca Coates is a curator, writer, lecturer and Director of Shepparton Art Museum since 2015.

I hope you get this: Raquel Ormella is a Shepparton Art Museum [SAM] and NETS Victoria touring exhibition

Venues

Shepparton Art Museum (Vic) 26 May – 12 August 2018

Horsham Regional Art Gallery (Vic) 13 October – 9 December 2018

Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery (Tas) 19 January – 24 March 2019

Drill Hall Gallery (ACT) 12 April – 9 June 2019

Noosa Regional Art Gallery (Qld) 22 June – 28 July 2019

Penrith Regional Gallery (NSW) 30 November 2019 – 2 February 2020