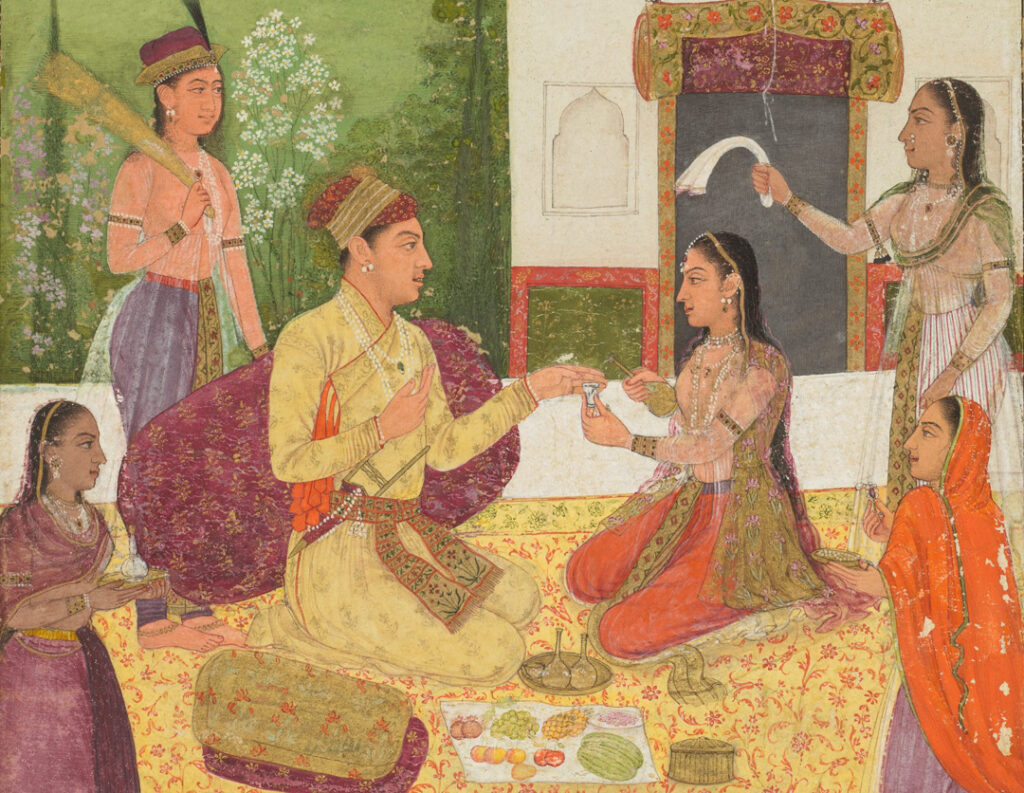

Women present vials of perfume to a prince and his companion. Detail from A Prince Conversing with a Woman While Taking Refreshments on a Terrace, c. 1701–1720, Gum tempera, ink, and gold on paper, 30.5 x 24.1 cm. Image courtesy of Cleveland Museum of Art.

Simran Agarwal finds an extraordinarily elaborate culture of fragrance in India’s Persianate world.

If we were to travel through time to the early modern period and pay a visit to the courts that dotted the Indian subcontinent, we would find ourselves in an environment of calculated decadence. These were gilded worlds, with an abundance of ornamentation, luxurious silks and velvets, populated by powerful people, rulers, connoisseurs and patrons of the arts. And all shrouded in a carefully created olfactory atmosphere, made up by scents conjured out of petals, leaves, woods and animal parts, using formulae that had been perfected and passed down generations.

As we journey through these courtly societies in the Deccani, Rajput and Mughal worlds, we discover that smell—its production, application, retention and distribution—pervades a range of environments, from leisure and play to encounters with god and royalty. Art historical and literary evidence of scents abounds. Perfumes, their implements and their use, make brief but recurrent appearances in detailed prescriptive texts, and in miniature paintings shown in expertly made objects such as bejewelled perfume holders, sprinklers, burners and diffusers.

Across regions, the use of perfumes was never simply an extension of luxury and indulgence. Instead, it was about understanding, curating and wielding scent’s inherent powers of transformation in daily social and political exchanges amongst the people of these worlds.

Perfumes were not simply external ornaments, like jewellery, make-up and clothes, nor were they innate attributes of beauty, such as a pair of beautiful eyes, a lithe physique or a melodic voice. Rather, they occupied a space in between these two categories: what James McHugh, in his book Sandalwood and Carrion: Smell in Indian Religion and Culture, classifies as “internal-external”: something that was worn externally but believed to affect the wearer, and those around him, in internal ways, mentally and physiologically.

Perfumed people

Although geographically diverse, the early-modern global empires of Safavid Iran, Ottoman Turkey and Sultanate and Mughal South Asia had many aesthetic and cultural forms in common. Whilst this was due, in some part, to their shared Central Asian ancestry, it was also because of their lingua franca, Persian, which, for about a thousand years (900–1900 CE), remained the language of knowledge production in the territories between Bengal and the Balkans. The incessant movement of people, texts, objects and ideas along commercial trade networks united them in a common language of adab, loosely translated as “etiquette” in English, but constituting wide-ranging social and aesthetic codes, gestures, expressions and actions. Scholars refer to these as Persianate societies, as they evidence the deep influence of Persian language, literature, arts and culture.

Within this network of behavioural norms proper to the elite men of Persianate societies, the art of perfumery occupied a central position as a marker of cultural refinement and superiority. Such markers distinguished elite men from women and other men of lower status. This is why so many manuals—including medical, culinary and religious texts—provided detailed instructions on the myriad ways in which perfumes could be made and, more importantly, used.

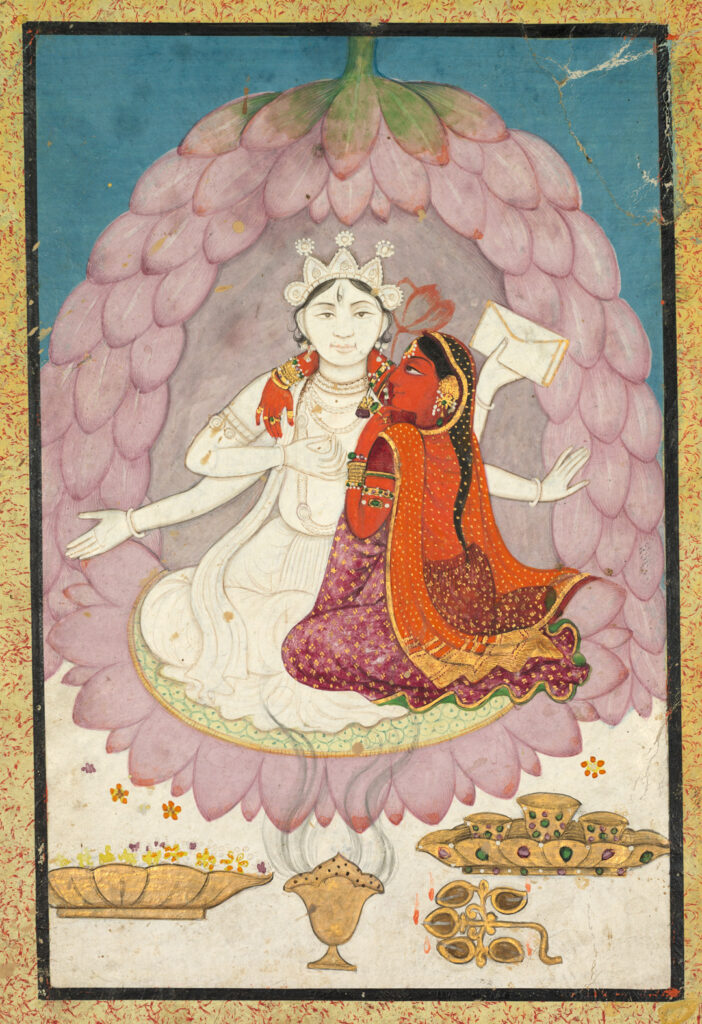

Indic traditions in the subcontinent had their own sophisticated discourses on good and bad smells, and the idea that scent could transform a space or a person was commonly accepted. Religious and mythological texts, such as the fifteenth-century Viramitrodaya of Mitramisra or the fifth-century Narasimha Purana, inform us of smells that are valued, the ingredients that make them up, and the effects of these scents, especially in the context of worship and adulation of gods and the purification of an environment. An integral part of worship has been the dispersal of good smells, generated from substances like camphor, sandalwood, saffron and aloeswood, using scented smoke, sprinkling scented water, and applying fragrant pastes on deities and in spaces.

Divine Couple Seated in a Lotus Blossom, early 1800s, Northern India, Pahari Region, Himachal Pradesh, Gum tempera and gold on paper, 13.3 x 9 cm. Image courtesy of Cleveland Museum of Art.

“Bad people” were often associated with unpleasant smells. In Hindu, Buddhist and Jain stories, they inevitably have to live with foul-smelling bodies at designated points in the cycle of births and rebirths. In fact, in this thought-world, most undesirable things and spaces—stale food, diseases, death and even hell—were associated with bad smells. On the other hand, good things, especially “good people”, were associated with good or auspicious smells, so much so that sandalwood was considered the ideal material for constructing figures of the Buddha.

The Mughal and other courtly elites seem to have incorporated such indigenous ideas surrounding smell within existing Persianate discourses on the art of perfumery. Jahangir, for example, famously noted in his autobiography that smelling foul air produced ill, idiotic and cowardly people. Conversely, fragrant breaths were considered signs not only of humoral balance but also of moral refinement and inner beauty. Thus, chewing on mouth fresheners and paan (betel rolls) and adding saffron and expensive olfactives to wine also became common practices in such courtly societies, adding a truly internal dimension to the “internal-external” use of perfumes in South Asia.

As many Rajputs and other regional royalty and noblemen were enrolled in Mughal imperial service under the mansabdari system, they too were initiated into discourses surrounding Persianate etiquette and self-refinement. Thus, even as Mughal power declined in the mid-eighteenth century, traditions surrounding beauty, etiquette and perfumery transcended sectarian and dynastic divides to get adopted at regional courts, such as those of Mewar, evoking ever more elaborate sensoriums of scented royal spaces.

When we examine the paintings and illustrations that emerged from the ateliers at these courts, we discover evidence of scent’s use in private and public contexts, indicating that it was an integral and accepted part of life in these courts. From portraits depicting rulers holding a flower to their noses, lovers offering fragrant paans or garlands to each other, and nayikas at their toilette applying scented pastes and smoke to their bodies or sampling perfume with their friends, to traces of perfumed sweat permeating the malmal jamas of elite men, perfuming practices formed an oft-repeated trope perfected in the visual landscape of early modern South Asia. While the details varied according to the desires and objectives of the artists and patrons, the smell of food, flowers and incense always saturated the paintings produced in these Persianate courts, whether they were ruled by Muslim or Hindu monarchs.

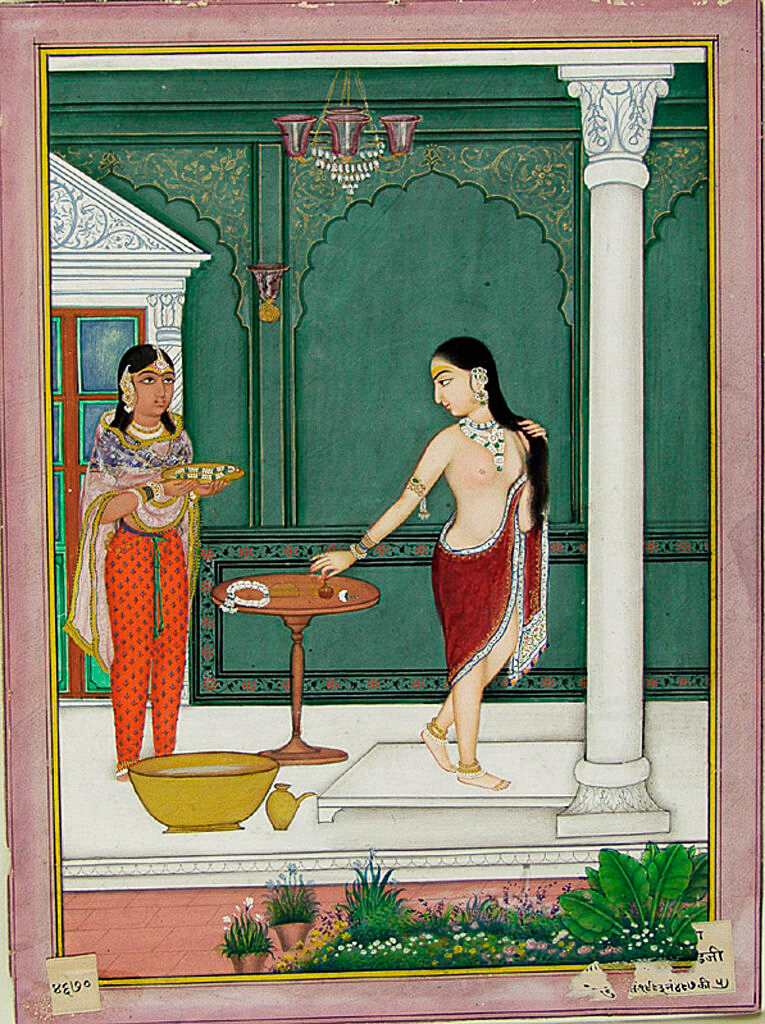

- A Nayika applying perfume after her bath. Detail from Vasakasajja Nayika After her Bath, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India, c. late 19th century – 20th century, Opaque watercolour and gold on paper, 28 x 20 cm. Image courtesy of Harvard Art Museum.

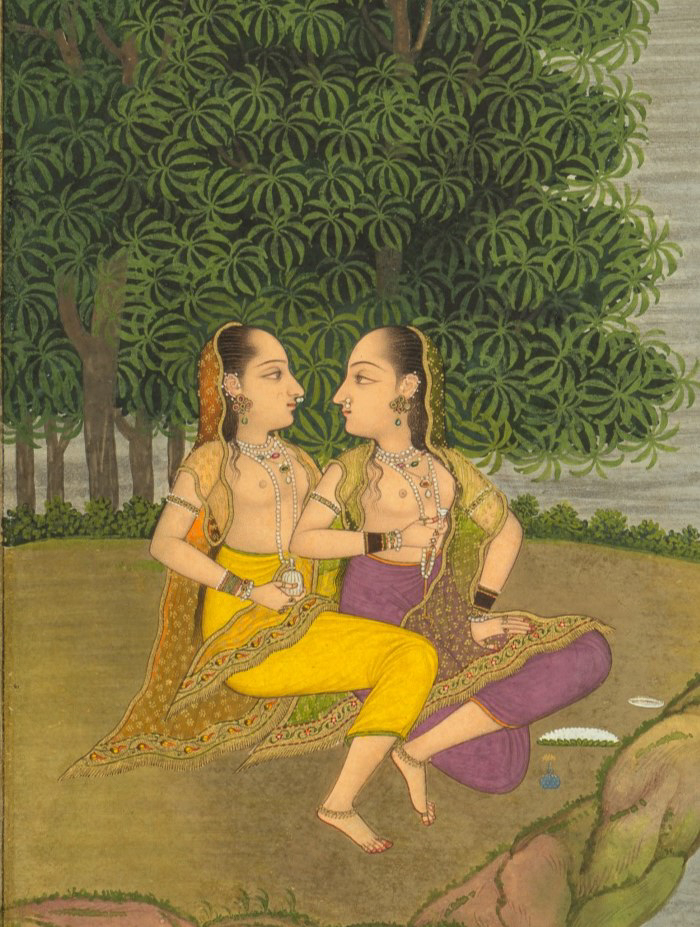

- Two women sample perfumes, and a bowl of leaves holds flowers. Detail from Women Enjoying the River at the Forest’s Edge, Murshidabad or Lucknow, India, c. 18th century, Gum tempera on and gold on paper, 33.1 x 24.9 cm. Image courtesy of Cleveland Museum of Art.

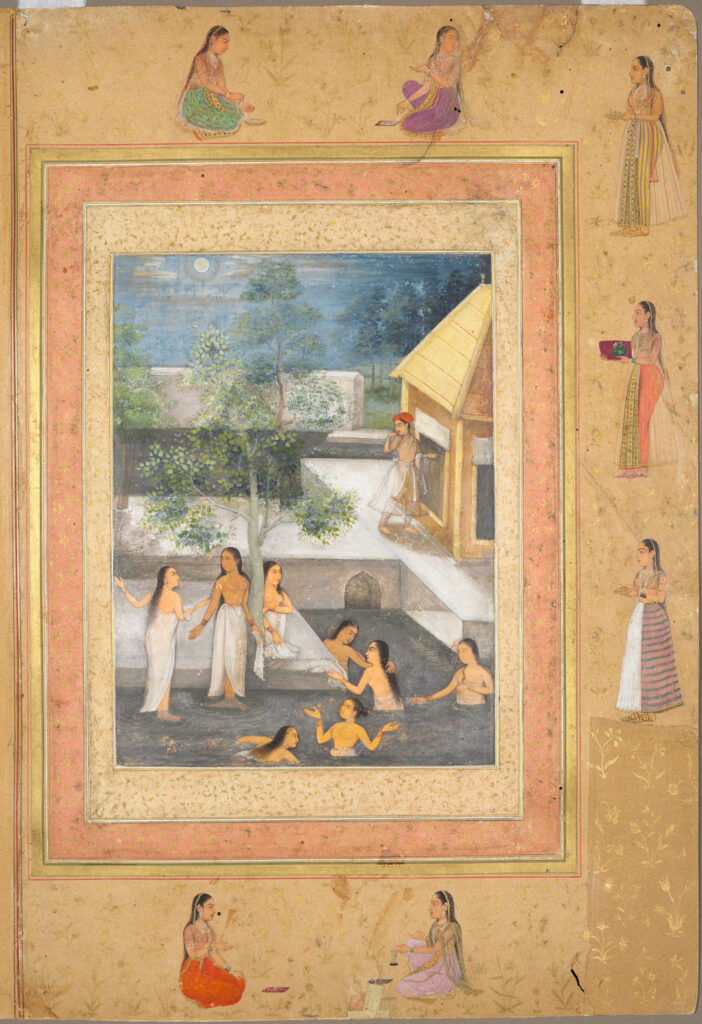

- An attendant at the top right brings perfumes for sampling. Harem Night-Bathing Scene, from the Shah Jahan Album, India, Mughal court, reign of Shah Jahan (1628-1658), c. 17th century. Image courtesy of Cleveland Museum of Art.

Given the profusion of perfumes in visual sources, it is hardly surprising that literary evidence from the period, especially prescriptive texts, also suggests the existence of specific systems and regimens of making and using bodily perfumes. An important early art historical record from the Persianate world that tells us about the elaborate rituals surrounding perfumery is the Nimatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi, a fifteenth-century cookbook from the Malwa Sultanate (covering present-day Madhya Pradesh and parts of Rajasthan). A lavishly illustrated book of recipes, it contains detailed instructions, formulae and ingredients to prepare sweet and savoury dishes, medicines and salves. Interestingly, it also gives recipes for perfumes and incense and explains how they might be used, from using a range of flower-based oils and adding roses to one’s bathwater to smearing saffron on the face, scented pastes on the joints, sandalwood on the throat and musk on the private parts.

It also explains how some perfumes are suitable for certain seasons of the year or hours of the day. Musks, saffron, citron, ambergris and watermelon, for example, are preferred during the winter months due to their heating properties whereas sandalwood and camphor are preferred in the summer months for their cooling effects. Floral fragrances, especially rose and narcissus, are thought to be inherently temperate and therefore used throughout the year.

- Preparation of aromatic paste,The Sultan Ghiyath al-Din, watching the preparation of ‘abtana’ (aromatic paste). Two servants working on it, one mixing ingredients in a large bowl, the other rolling out the paste. Outdoor scene against a landscape of heavy vegetation and a gold sky. Opaque watercolour. Sultanate style. Image taken from The Ni’matnama-i Nasir al-Din Shah. A manuscript on Indian cookery and the preparation of sweetmeats, spices etc. Originally published/produced in 1495 – 1505.

- Perfumes and flowers,The Sultan’s bedroom being prepared with perfumes and flowers. Advice on the domestic use of perfume. Ghiyath Shahi is not present. His couch with a large cushion and two plates of (?) betel chews is in the centre under an awning. Other dishes and plates in the foreground together with flasks and jars. The section on the use of perfume in the house. Opaque watercolour. Sultanate style. Image taken from The Ni’matnama-i Nasir al-Din Shah. A manuscript on Indian cookery and the preparation of sweetmeats, spices etc. Originally published/produced in 1495 – 1505.

- Preparation of perfume,Preparation of perfume for the Sultan Ghiyath al-Din. Opaque watercolour. Sultanate style. Image taken from The Ni’matnama-i Nasir al-Din Shah. A manuscript on Indian cookery and the preparation of sweetmeats, spices etc. Originally published/produced in 1495 – 1505.

- Preparation of rose water,Preparation of rose water for the Sultan Ghiyath al-Din. Opaque watercolour. Sultanate style. Image taken from The Ni’matnama-i Nasir al-Din Shah. A manuscript on Indian cookery and the preparation of sweetmeats, spices etc. Originally published/produced in 1495 – 1505.

- Preparation of frankincense,Preparation of frankincense for the Sultan Ghiyath al-Din. Opaque watercolour. Sultanate style. Image taken from The Ni’matnama-i Nasir al-Din Shah. A manuscript on Indian cookery and the preparation of sweetmeats, spices etc. Originally published/produced in 1495 – 1505.

Two centuries later, we have the Itrya-i e Nauras Shahi, a seventeenth-century text on perfumes from the Adil Shahi kingdom of Bijapur in the Deccan (in present-day Karnataka). “It is incumbent that all created beings, particularly the followers of the Prophet, use perfumes and share them with one another,” says the text, before proceeding to enlist in its various chapters the precise origins of different musks as well as their specific qualities and uses. These include detailed instructions for perfuming clothes, such as scattering flowers and musks within their folds, and spraying scented water and smoke onto the fabric.

- Perfume sprinkler. Northern India, 18th century, Glass, mould blown, enamelled and gilded, 14 x 5.7 cm. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Spittoon or Incense Burner. Bijapur or Golconda, Deccan, late 16th–early 17th century, Brass, 22.9 cm. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

To understand why such care was taken to underline the importance of wearing perfume, in specific ways and at specific times, we must approach scents as agents not only of aesthetic adornment but of medicinal and humoral cures, as the medieval Persians did.

Emma J. Flatt is a scholar who works on the socio-political significance of perfumery in Deccani courts, in both Indic and Perso-Arabic medical treatises. She explains that smells—along with food, drink and medicine—were believed to play an important role in balancing the psychological and physical health of the body. For example, fragrant substances which were considered to be inherently cold were used to treat imbalances caused by an increase of warm bodily humors, historically associated with fluids like yellow bile. Reciprocally, warm fragrances were employed to treat imbalances caused by an increase in cold bodily humors, associated with phlegm and black bile. Certain smells, especially those considered “good,” were also thought to have a direct effect on the dil or heart of their inhalers, swelling it in size by filling it with farah or joy. Such joy could be of various kinds, ranging from the emotional and sensual to the intellectual.

Given this transformative power of perfumes, much care was taken with the formulation and the ingredients that went into their making. Merchants and traders often embarked on perilous journeys to acquire specific musks, aromatics and incense. These substances, by the time they reached local markets, were almost always too expensive to be available to the masses and, as the preserve of the wealthy, were only consumed in aristocratic spaces, such as mansions, palaces, courts and temples.

Scented worlds

The Nimatnama gives us precise instructions on how the walls of the king’s palace should be rubbed with abir, a scented paste that follows a particular formula involving “mango, ambergris, beans, marhatti aloes, perfumed fat, bruised grain, chauva, essence of mouse-ear plant, Chinese camphor, boiled juice of spikenard and … flowers scented with aloes, white sandal essence, scent from shoots, sesame oil scent, sweet basil essence, champa essence, artemisia essence, turmeric leaves essence, sacred basil essence, cardamom juice, sandal juice.” The manuscript also shows illustrations of an audience hall fragrant with the smell of flowers sprinkled across its floors as well as the candles and incense sticks burning in its foreground.

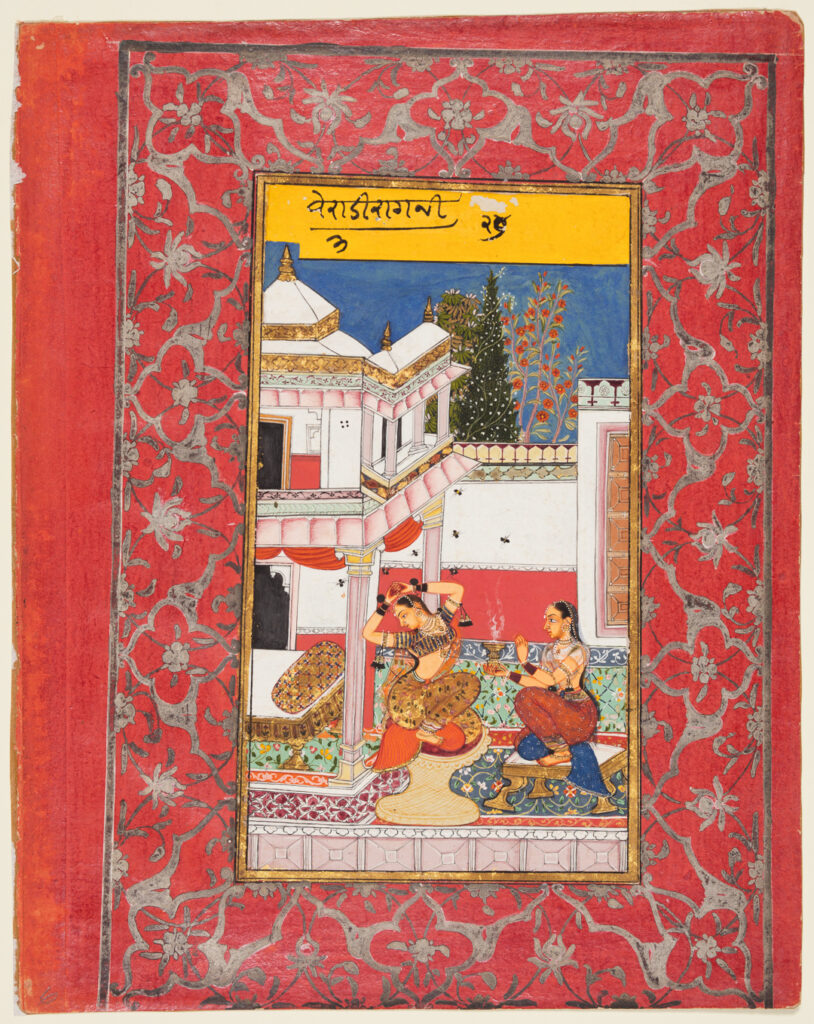

Besides listing complex ingredients, books like the Nimatnama and the Itrya-i e Nauras Shahi, when read in conjunction with paintings from the period, also introduce us to an idea that has prevailed across centuries and cultures — that spaces too are worthy of perfuming.

Images from across the subcontinent reveal to us the importance of smell in setting the mood, whether formal or intimate. We observe this across paintings produced not only in Islamicate Persianate courts—such as those in Malwa, the Deccan or Northern India—but also in those created in the Rajput courts in Rajasthan and the Punjab Hills regions. We see amorous scenes set in fragrant groves of blossoms; spaces prepared with incense burnt using elaborate diffusers, strategically placed trays or garlands of flowers and aromatic pastes rubbed on the walls; and gardens planned so as to allow fresh blossoms to scent the air.

Incense being burnt in the painting Woman Longing for Her Lover: Verati Ragini of Dipak, from a Ragamala, 1650–60, Northwestern India, Rajasthan, Rajput Kingdom of Kota, Gum tempera, ink, gold, and silver on paper, 30.2 x 24.2 cm. Image courtesy of Cleveland Museum of Art.

Smells were strategically introduced in spaces in order to attract and repel beings, whether lovers, animals or supernatural creatures. In spaces like the palace desirable smells could be used to regulate and fine-tune the moods and dispositions of the king and his courtiers, while in places of worship they could be used to please the gods through aromatic preparations, especially those featuring the cooling and costly sandalwood.

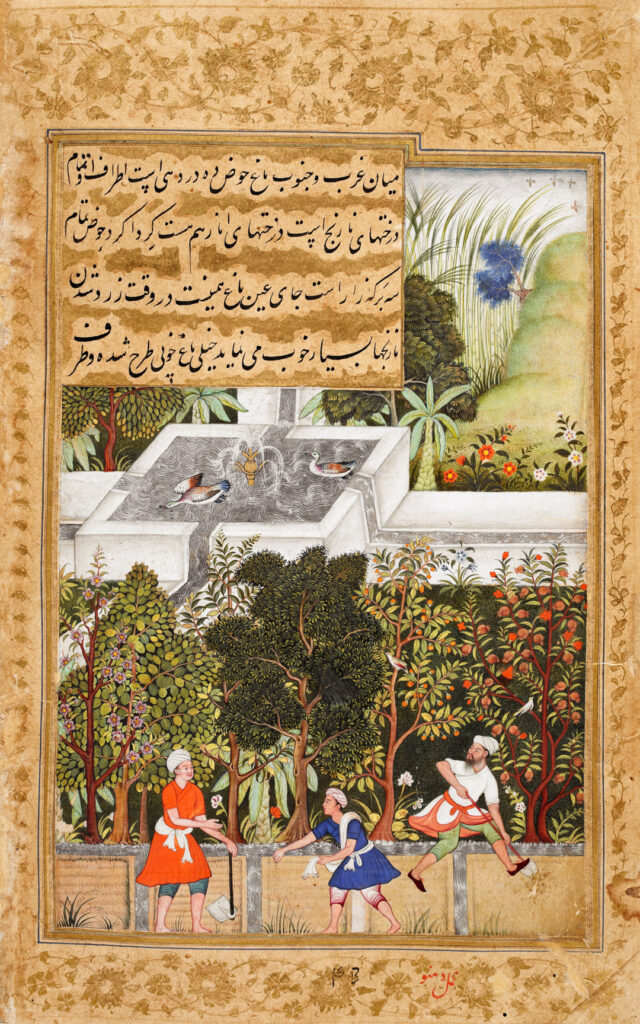

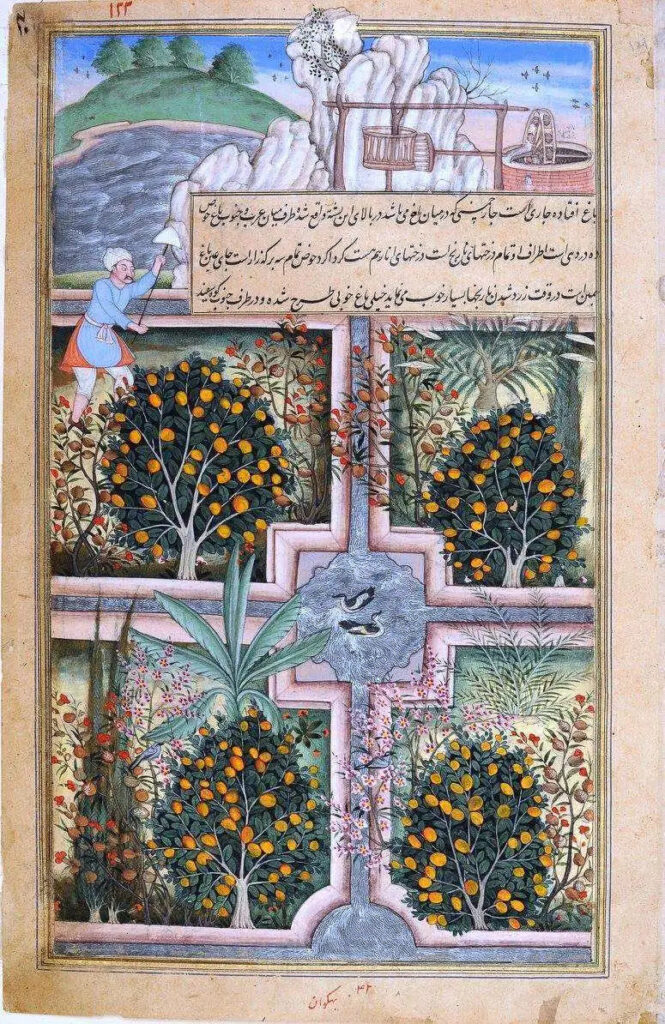

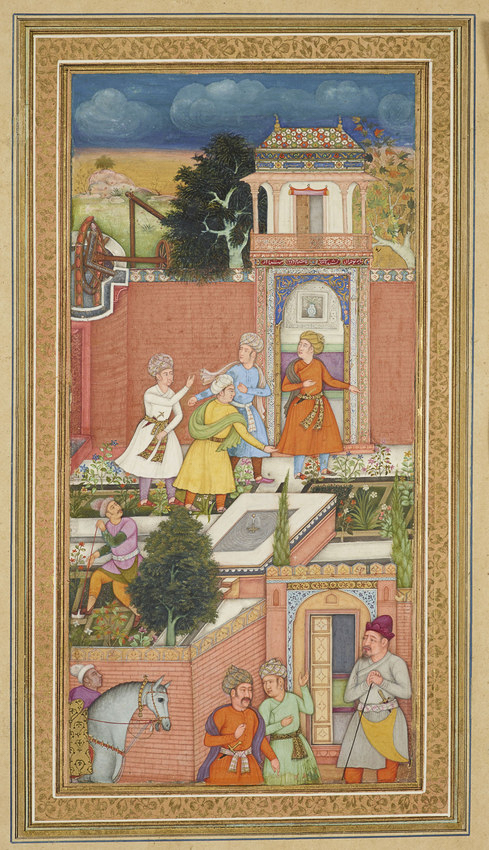

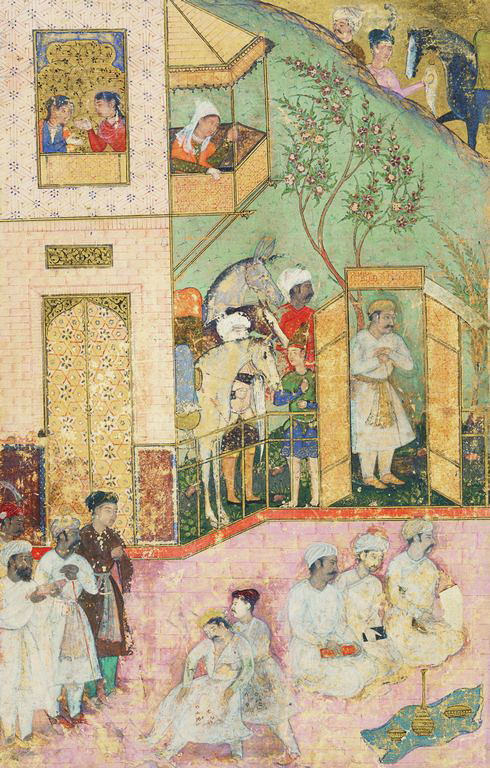

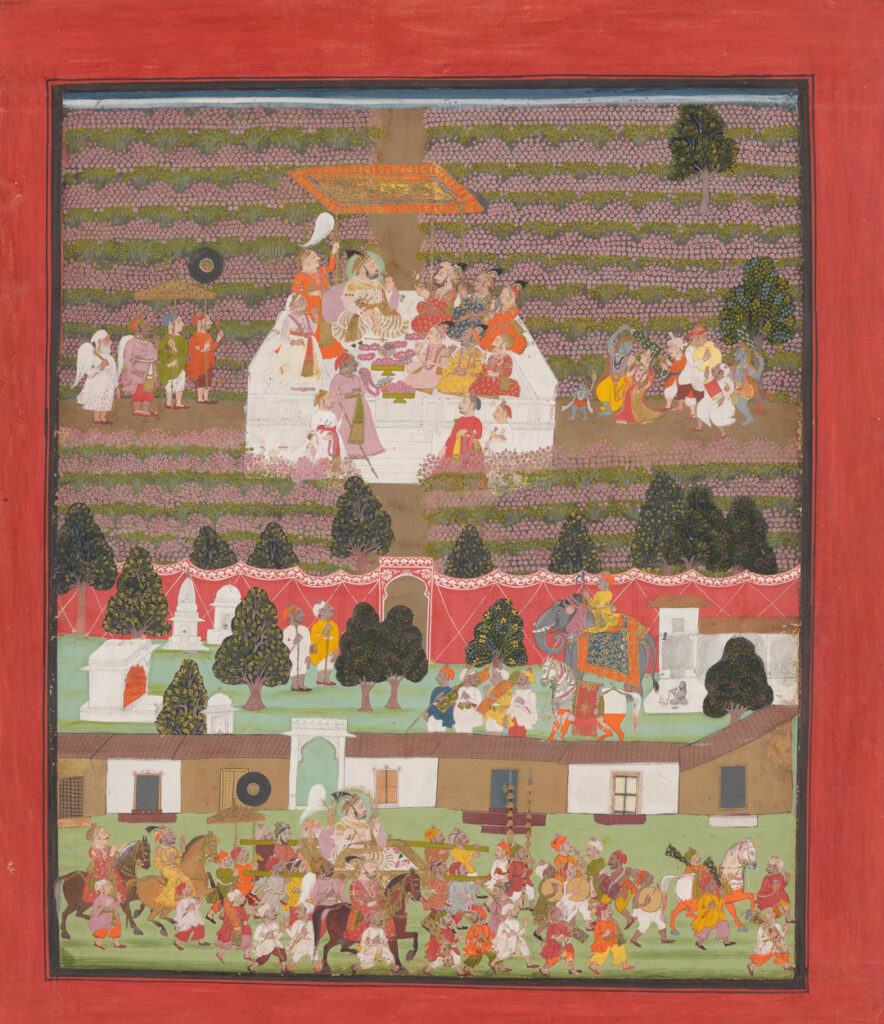

By the early decades of the sixteenth century, outdoor gardens with planned rows of flowering plants and fruit trees were popular amongst the Mughals, as venues for both the majlis or elite parties and gatherings, as well as quiet leisure in solitude or with a few companions. Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty, was in the midst of war throughout his life and spent most of his time outdoors, camping from one battlefront to the next. According to his autobiography, he would often stop at gardens for leisure and rejuvenation with his entourage. A favourite was the Bagh-i Wafa in Kabul, resplendent with fragrant fruit trees like the orange and pomegranate. This and other Mughal gardens also commonly featured streams and small enclosures containing still (often scented) water. But the Mughals were aware that still water could quickly become stagnant water—a bearer of bad smell—and therefore, almost as a rule, installed water wheels in order to continually refresh the surface water. Babur’s great-grandson, Jahangir, too was known for arranging many majlis in garden settings, where music, poetry, scented wine, flowers and flowing water were enjoyed by his courtiers.

- Construction of the Bagh-i Wafa. Attributed to Dhanu, Northern India, c. 16th century, Opaque watercolour on paper. Image Courtesy of the British Library.

- Bagh-i Wafa featuring a water wheel. Northern India, c. 16th century, Opaque watercolour on paper. Image courtesy of the National Museum, New Delhi.

- Men in a Garden. Northern India, c. early 17th century. Image courtesy Royal Collection Trust.

- A Majlis. Balchand, c. 1605, Opaque watercolour with metallic paints, 30 x 20 cm. Image courtesy of Royal Collection Trust.

The most intriguing and visually rich example of perfumed spaces, however, comes from the court of Maharana Jagat Singh II of Mewar, a Rajput kingdom in present-day Udaipur. Here, the distinctively affective atmosphere that had permeated Mughal literature, paintings, and practices was not only adopted but also localised and, in fact, expanded across political, cultural and religious milieus.

In a painting showing the maharana visiting the Gulab Bari or rose garden, we see the king twice: first being carried by his entourage towards the venue and, second, seated on a canopied pavilion amongst his companions. Unending rows of bushes turned pink by blooming damask roses surround the king and his attendants, who are themselves seen holding and smelling the flowers. The industrial-scale plantation, accompanied by the trays and garlands of pink roses placed on the pavilion, make the scent of the flower the indomitable theme of the painting. Here, as in many other spaces, such elements also add a visual dimension to perfumery practices; showing us how perfumes, in early modern South Asia, could also take on a performative aspect as the necessary accoutrements to state rituals and ceremonies.

Raghunath, son of Maluk Chand, Maharana Jagat Singh II celebrating the Festival of Flowers in the Gulab Bari Garden, 1750, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Felton Bequest, 1980. Image ID: Cd100194 Web: http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/explore/collection/work/53511

Perfume around us

By its very nature, scent travels and spreads through the air, and so too do we follow it and delve into the myriad ways scent has been wielded. Along the way, we discover complexities that tie together politics, socio-cultural relationships, belief systems, and entire ways of being. Tracing the history of scent is a strange and exciting endeavour: the smells themselves are absent, but we are always aware of their existence and importance, through little clues that suffuse paintings and wordscapes from centuries ago.

Perhaps the most wonderful thing about perfume is that it allows us to bring the natural world into the spaces that we inhabit, into our bodies and our minds, and that of others. The beauty of a flower or a tree or an animal is fleeting. All things perish, but through perfumery, with our ever-improving formulae and methods, we learn to distil their essence to have it linger within and around us.

Perfumes, both then and now, have been used to perpetuate and strengthen class divisions, and have been used to signify one’s status. Giving off a pleasant smell continues to remain an indication of taste, refinement, wealth and above all, one’s class in society. Despite a difference in appearances, lifestyles and the chasm of centuries that separates us, we aren’t very different from the people who inhabited these opulent early-modern courts and worlds: perfumed kings, queens and nobles, in their perfumed palaces and gardens. We continue to be in the thrall of smell. Entire industries are dedicated to its production and we continue to wear carefully chosen scents, as we continue to perfume our spaces, in the hopes that we can leave a certain impression on the people who pass us by.

This article is written by Simran Agarwal, MAP Academy. The MAP Academy is a non-profit, open-access educational platform committed to building equitable resources for the study of art histories from South Asia. Through their freely available digital offerings — Encyclopedia of Art, Online Courses, and Stories — they encourage knowledge-building and engagement with the visual arts of the region.

Bibliography

Kia, Mana. “Persianate ‘adab’ involves far more than elegant manners.” Psyche. October 12, 2020. Accessed July 11, 2023.

McHugh, James. Sandalwood and Carrion: Smell in Premodern Indian Religion and Culture. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

McHugh, James. “Seeing Scents: Methodological Reflections on the Intersensory of Aromatics in South Asian Religions.” History of Religions 51, no. 2 (2011): 156–77.

Singh, Kavita, ed. Scent upon a Southern Breeze: The Synaesthetic Arts of the Deccan. Mumbai: Marg Foundation, 2018.

Roth, Nicholas. “Visual Nosegays: Plants and Scent in Early Modern South Asian Painting.” Baghehind. March 01, 2022. Accessed July 11, 2023.

Vermani, Neha. (2023) “The Perfumed Palate: Olfactory Practices of Food Consumption at the Mughal Court.” Global Food History (2003): DOI: 10.1080/20549547.2023.2203603.