Māori named the two main islands of New Zealand Te Ika-a-Māui (the fish of Māui) and Te Waipounamu (the greenstone waters). These are certainly more romantic descriptors than North Island and South Island, the default names the islands received during their 200 or so years of European colonisation.

You could use this example of naming as a simple metaphor for the differing attitudes of the two peoples that chose to make these islands their home. For Māori the source was found in myth and material, for Pākehā (Europeans) the pragmatic position of each island on the map sufficed.

The matter of poetic weight – or lack of – aside, these descriptors have recently become of concern to us in Aotearoa New Zealand because it appears our islands have never been officially named. This oversight, and the need for correction, means that now official status has been granted to both the European and Māori versions.

The northern island Te Ika-a-Māui (the fish of Māui) is so named because the Māori creation story has it as a large fish hauled to the surface by a demigod called Māui. I have a bit of jewellery history with this story – four bits actually. I once made a suite of four pendants that named the parts of Māui’s fish: the tail, the fin, the eye and the mouth. It also included a hook.

Māui’s fishhook – in the myth, carved from his grandmother’s jawbone – has also become a set piece in New Zealand adornment history. Due to its symbolic importance, the fishhook transformed from a functional object to a wearable one within Māori art. The result is the hei matau, the fishhook pendant.

I live in the north of Te Ika-a-Māui near the tail of the fish. Since moving with his family from Germany to New Zealand, fellow jeweller and co-curator of the exhibition Karl Fritsch has been living on the jaw of the fish’s mouth. Living by the sea strait that separates the North Island from the South Island, Karl has developed an interest in ocean fishing. He came to New Zealand, went fishing and bought the T-shirt.

Language brims with fishing idioms and metaphors. Perhaps with our Māui back-story New Zealanders are more disposed to featuring them. Whatever the reason, as the two people charged with selecting the work for WUNDERRŪMA, Karl and I developed an immoderate fondness for using fishing terms when talking about the task of collecting New Zealand jewellery for showing in Germany.

Fishing was an appropriate motif for our curatorial intent – our ‘kaupapa’ – because while we knew we wanted lots of jewellery, we had no idea what that would look like. Our first hook caught at the back of Te Ika-a-Māui’s throat. The Dowse Art Museum in Lower Hutt, Wellington, agreed to assist us with the logistics of putting the exhibition together for travelling to Germany. The Dowse also has a large collection of contemporary New Zealand jewellery from which we could draw works for our show.

The heavy shoals of objects that swim in institutional drawers seemed an easy catch. We went fishing at New Zealand’s national museum, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa), for further examples of adornment – particularly work by Māori made in pounamu, the prized green nephrite jade. Pounamu has one major source in New Zealand: the southern island. So there we encounter the other island’s name, Te Waipounamu (the greenstone waters).

Pounamu’s translucent qualities made it particularly suitable for pendant forms strung from the ear – the kuru (long and straight) and the kapeu (long and curved at the end). Pre-European Māori were a stone-tool culture, so the other qualities of pounamu: a hardness and edge keeping akin to steel meant it was of political and economic interest. In a similar way, but for different qualities, gold held interest for Europeans. Europeans arrived in great numbers to the South Island of New Zealand in the 19th century looking for gold.

Although pounamu and gold were important within each respective culture during this early period of Māori-Pākehā contact, neither material was of much interest to the other group. By the late 1880s, however, some Māori had joined the search for gold, and Pākehā lapidaries made work in pounamu for Māori.

The Pākehā lapidaries also supplied the growing tourist souvenir market for Māori objects. Interestingly, in the early 20th century this industry was undermined by the export of pounamu to the gemstone-cutting centre of Idar Oberstein in Germany. In Idar Oberstein pounamu was processed into jewellery items for sale back in New Zealand.

The exhibition is titled WUNDERRŪMA. In part, the name stems from New Zealand’s history of being called a scenic wonderland: a “wonderland of the Pacific”, a “thermal wonderland”. These were 19th-century slogans created by marketers to attract tourists to our land. Wonderland was a big claim back then, but it seems little has changed. The marketers currently charged with promoting the country, Tourism New Zealand, are using the slogan “100% Pure” to do the same job.

The title also comes from the idea of early Wunderkammer: collections of objects whose categorical boundaries were often ill-defined. Wunderkammer tended to be random collections of objects from exotic cultures, collected by enthusiastic, dilettante, ethnologists and explorers. Where WUNDERRŪMA differs from Wunderkammer is in the reliability of attribution. Wunderkammer were collected with external eyes. The creators of the objects were from elsewhere, and the curator’s interest was in the ‘other’. In contrast, WUNDERRŪMA uses an internal curatorial scheme based on a particular knowledge – that of the maker.

Our curatorial interest is on show in WUNDERRŪMA, but it’s an interest in the ‘us’ not in the ’other’. For me, working on WUNDERRŪMA reignited a curiosity about my own field of contemporary jewellery, and in particular how that field manifests itself in New Zealand. I think wonder worked best for us as a verb: the desire or curiosity to know something.

Perhaps that curiosity was helped by the fresh eyes Karl brought to the task. Karl had an ability to see past my set attitudes – grown over thirty years of immersion in the field – and to question my prejudices regarding the practice of contemporary jewellery here in New Zealand. What I thought of as cliché could be distinctive to him. I had to look again.

And the RŪMA? Rūma is a Māori word transliterated from the English word room, and a verb: to make room. RŪMA overlaps both languages. Stretched over two cultures and compounded with WUNDER, obviously a German word, we could also say WUNDERRŪMA spans three cultures.

On the face of it, Karl and I have very different backgrounds and styles of making. However, like the title of the exhibition, these differences readily compounded and transliterated into our own language of curation – our kaupapa.

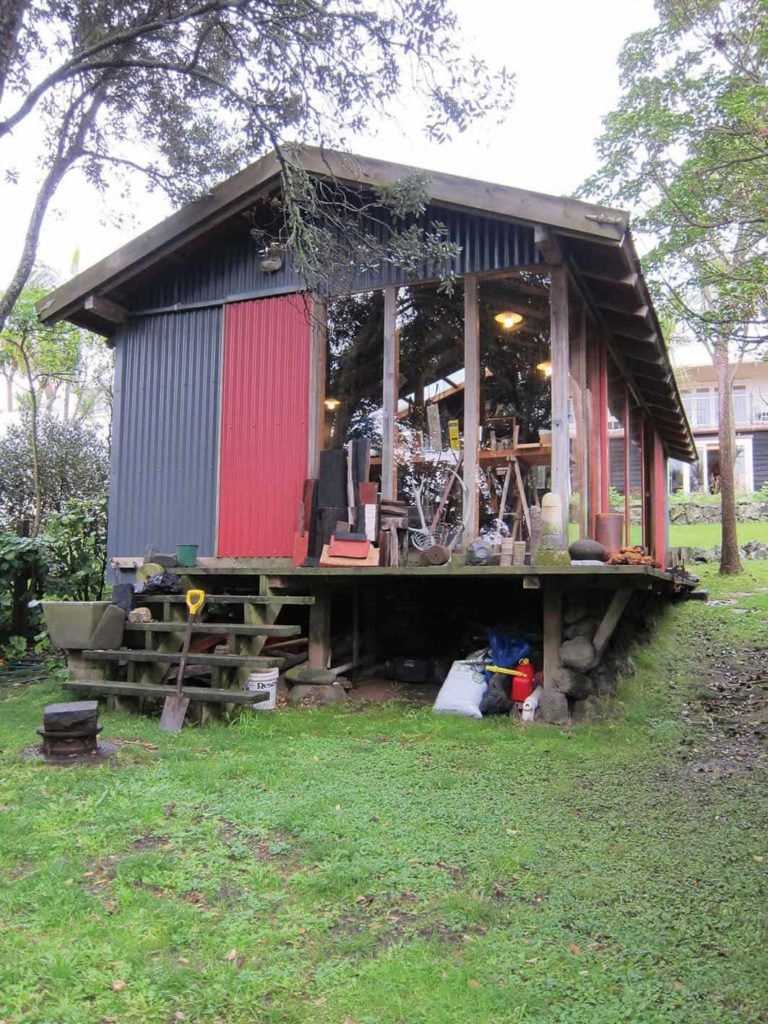

We had a method. It involved going out and looking at work in galleries, workshops and institutions. We visited artists in their workplaces in both Te Ika-a-Māui and Te Waipounamu. These were planned trips, but subject to artists’ availability, feasibility and our budget – like a fishing trip with about as much potential for fluky good luck and bad fortune. We didn’t see everything, but we saw a lot.

Fishing might have been our organising metaphor, but the aggregating principle we worked with was thinking in clumps. Clumping comes from biology. It’s when species group together for mutual benefit. You can see it on the rocky shoreline where you find different species of sea life grouped on the rocks.

It seemed appropriate to engage mutual benefit to group the jewellery. If two pieces felt right together they formed the potential to be a category. Sometimes it was a clump of one, but even then it was contingent on the existence of others. It was as a cohort that much of the work took its meaning or its place in the show. Work was included when it demonstrated a rapport with other work. This relativity may not always be obvious, but it always had a presence in our discussion.

We never denied a piece of jewellery the meaning intended by the artist. We also never took that intent as a reason for inclusion or exclusion. If there was a narrative to be told it was the emerging narrative of the exhibition as a whole. If a work didn’t align itself with that bigger narrative then its own story was rarely a cause for it to be included.

We decided the work in WUNDERRŪMA could come from any time in New Zealand’s adornment history. We even gave the exhibition the working subtitle: 1000 years of New Zealand contemporary jewellery.

There’s obviously a tongue-in-cheek intent with that byline. Current archaeological research places the earliest human habitation of New Zealand at around 700 years ago. For 300 of those 1000 years no one lived on these islands to make any jewellery. However, we also had a serious intention to flatten what constitutes ‘contemporary’ in art, and its use as a defining term in our own field of ‘contemporary jewellery’.

Besides, shouldn’t contemporary have a different meaning in a country such as New Zealand with a short history of human occupation relative to one like Germany that has had several millennia of human habitation?

Another reason to question what was contemporary became apparent in our visit to Te Papa to look at the Māori collections for work to include in the exhibition. Māori have their own view on how time works – a view that the past unfolds in front of you.

That viewpoint also applies to objects. For Māori, objects exist on a continuum not only as pieces of jewellery, but also as ‘taonga’ (broadly – treasures). The Mātauranga Māori curators at Te Papa told us the work represented ancestors. For Māori, the work was still functioning in a contemporary space.

I said before that the work contained in museum drawers looked like an ‘easy catch’ for an exhibition curator. But, despite their apparent limbo, it turns out they still belong to someone. (For example, see Areta Wilkinson – Taonga are not Jewellery, on page 75).

The oldest examples of jewellery in New Zealand probably came from elsewhere in Polynesia, arriving with the first inhabitants around 700 years ago. The first jewellery made here, however, was likely similar to examples found in burial sites on the Wairau Bar (in the northern part of Te Waipounamu).

Necklaces and pendants excavated from the Wairau Bar have a Polynesian character, but are made from material exclusive to New Zealand. As is so often the case, and Aotearoa is no exception, jewellery is very present in the record of human history afforded to us by artefacts.

As well as looking to the past, we looked at jewellery that had been made within practices outside of contemporary jewellery: work by artists with established practices unrelated to jewellery-making, and some work by makers who were barely established. Reputation was never a determining factor, although there were some fishing grounds we never dropped a line in.

Being constrained by our own experience meant contemporary jewellery was still the easiest species to catch. For that, well, we had a particular eye – perhaps evident in the number of works relating to functionality, whether suggested or actual. It might be a particularly male eye. It‘s not an eye for ‘beauty’ – the kind voted for by a large constituency. That’s pretty hard to spot in WUNDERRŪMA, a situation not uncommon with contemporary jewellery aesthetics anywhere in the world.

I’m not saying that beauty isn’t present in New Zealand contemporary jewellery in quite recognisable, and classic, forms. It’s just that we didn’t catch a lot of it on this fishing trip.

More of that New Zealand jewellery ‘beauty‘ was probably on display in another exhibition which travelled from New Zealand in the late 1980s, called Bone Stone Shell: New Jewellery New Zealand. It toured to Australia and Asia.

It would probably never have occurred to me to mention Bone Stone Shell in this introduction had the exhibition, in an ‘as I write this’ moment, not reappeared. Bone Stone Shell: 25 years on is currently on show at Te Papa.

Bone Stone Shell, that three-chord riff in New Zealand jewellery-making history, is a 1980s exercise of New Zealand clumping practice. It painted an idealistic picture (I think it had some stake in our Wonderland self-image), and one that had the jewellers in tune with nature through material, motif and lifestyle.

Bone Stone Shell also had a nationalist impulse that tracked with other emerging political and social attitudes of the time. It now looks like a news broadcast from the period. But then again, because of particular political and social conditions in New Zealand in the 1980s, it did have news to broadcast.

Does WUNDERRŪMA have anything to broadcast, or is it all nuance and no news? There is news about Aotearoa New Zealand in WUNDERRŪMA, but, like most information now, it has fractured into many different sorts, and countless niches. We find it still likes to gather, just not in the specific way it did in Bone Stone Shell around identity issues. That said, the emergence of new folklore around pounamu or around motifs like the hei matau, shows that identity does remain a part of our fractured story.

WUNDERRŪMA might not have the same communal identity as Bone Stone Shell did – it wasn’t there to be found this time around. By another measure, however, WUNDERRŪMA is a more communal expression of what New Zealand makers are doing. There are now many more makers – 12 artists were in Bone Stone Shell, 75 are in WUNDERRŪMA.

These artists are connected to each other in a way that couldn’t be imagined in the 1980s, and are also connected further afield. Networks that had beginnings in the 1980s and ’90s with visits by makers, and teachers, from Europe and America have turned into durable connections. Certainly many makers have virtual links with overseas colleagues; and many are making the trip to Schmuck, the annual art fair for jewellery that is held every March in Munich.

Despite its sprawling inclusiveness our exhibition (and any exhibition for that matter) will always be a contracted thing, a constricted version of the news. In the end WUNDERRŪMA is simply what interested the curators – that was our essential kaupapa.

One of the materials that had a resurgence of use in the Bone Stone Shell era was the shell of New Zealand abalone pāua. For as long as I can recall, after the flesh of the pāua was removed for eating, one of the most common uses of the shell (apart from being a material for jewellery) was as an ashtray. There used to be a piece of graffiti on a wall in my city that read “like a paua needs an ashtray“ – a take on the adage: “like a fish needs a bicycle“.

There aren’t any pieces made from pāua shell in WUNDERRŪMA, but I’m reminded of this graffiti because, weirdly, there is a clump of works made from cigarettes. Where did that jewellery-making impulse come from? Some fag-end moment in our wonderland story, or a poke at our ‘100% Pure‘ image? A Bone Stone Smell moment in New Zealand contemporary jewellery? Perhaps, more practically, it’s jewellers creating amulets to help purge their addiction.

Whatever the motivation, as in that mixture of the poetic and prosaic in the naming stories of Aotearoa New Zealand, we find a narrative in the mix of possibilities. I don’t find writing a narrative around what Karl and I caught for this exhibition very difficult to do, but then, like the tales fishermen tell, you might just choose not to believe us.

Author

Warwick Freeman has been a jewellery maker since 1972. He is still a jeweller maker. He lives and works in Devonport, Auckland. In 2014 with Karl Fritsch he curated Wunderrūma, Schmuck aus Neuseeland for exhibition in Munich. After returning to New Zealand Wunderrūma was exhibited at The Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt in 2014 and The Auckland City Art gallery in 2015.

Warwick Freeman has been a jewellery maker since 1972. He is still a jeweller maker. He lives and works in Devonport, Auckland. In 2014 with Karl Fritsch he curated Wunderrūma, Schmuck aus Neuseeland for exhibition in Munich. After returning to New Zealand Wunderrūma was exhibited at The Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt in 2014 and The Auckland City Art gallery in 2015.

This is a catalogue essay for the exhibition WUNDERRŪMA.

Comments

great article warwick, many thanks