Santiago Carbonell Paths of words and silences, of men and women, of memories and forgetfulness (detail Men) 2010 mural, Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, Mexico City.

Last year I visited the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, Mexico City, to view a mural by contemporary Spanish Ecuadorian artist Santiago Carbonell (b. 1960), which I had been assigned to discuss to a tour group as part of a Law and Society Association conference.

After scrolling through virtual details online, it was a relief to finally stand before the mural. Until then I had seen figurative paintings on a screen punctured by what I thought were white rectangles; yet, in the flesh, I realised they were a vital edit: a deletion of actual doorways and windows that are arguably part of the work. My task was to discuss the art of justice to a tour group, but this discovery, omitted in reproduction, caused me to wonder again about the proverbial “truth” of the “image” in general. The treachery of the reproduction reflected a feeling I already had about Carbonell—his portrait of President Felipe Calderón (2012) had cost too much, just under $52 000, in a country whose people had too little. I wondered if the mural had also cost too much. Commissioned in 2010 to commemorate the Bicentennial of Independence and the Centennial of the Mexican Revolution, it portrays farmers and activists hyper-realistically in order to reflect the demand for justice and equality at the centre of both movements. Standing in the middle of this dark cavernous space I considered how the mural resonated—both symbolically and materially—with the “mirror of justice”.

Just as the Aztec deity Tezcatlipoca was associated with the night sky and night winds, dark seems to fall in the scene entitled Men, where a man holds a scythe and another pushes weapons. The gilded silhouette of Tezcatlipoca in jaguar form foregrounds this narrative, surveying the scene, and is a walking mirror of sorts. In Men, draped cloths of red perhaps recall the “red battalions” who fought against the Zapatistas during the revolution, or denote the blood of the heroes who fought for independence—but also the blood of those who are presently losing and have lost their lives to the war on drugs. In the background, a sepia monochrome of workers and peasants—perhaps referencing the first peasant and world revolution of the 20th century—portrays people as active agents of national formation in union and solidarity. In Carbonell’s walls, a ‘revolutionary nationalism’ is conveyed without being overly didactic.

Other parts of the mural are dominated by green and white cloth, which combine with the red of Men to form the colours of the Mexican flag.

Green cloth—denoting, on the flag, freedom, light and hope, as well as independence from Spain—weaves through the painting entitled Women. The work is full of visual analogies—another form of mirroring whereby meaning is duplicated but in a slightly different form. Here, female figures stretch their arms upwards, analogous to the doves emerging from the cave. As if proclaiming liberty, they look up to the sky and we feel elevated, uplifted; their ascent charges the crucifix-like beams of destruction depicted behind them with paradoxical construction.

Santiago Carbonell Paths of words and silences, of men and women, of memories and forgetfulness (detail Women) 2010 mural, Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, Mexico City.

An idealised promise of justice for Mexican women suggestive of revolution, youth and religion is presented here. Women appear as builders of the future and the corn fields behind them suggest their fertility. Their limbs vector towards each other, creating a sense of magnitude, and they direct their attention to each other, hands and hearts joining in a coordinated system of solidarity and strength. These dramatic groupings become powerful centres that unite the present and past. Here another silhouette, this time the gilded form of an eagle, symbolises light and direction. On the Mexican flag, the eagle is the dominant emblem on the central coat of arms. It recalls the legend of an eagle perched on a cactus—a sign from their god, Huitzilopochtli—that signalled to the Mexica people (who would become part of the Aztec Empire) where to establish their new city, Tenochtitlan, modern day Mexico City.

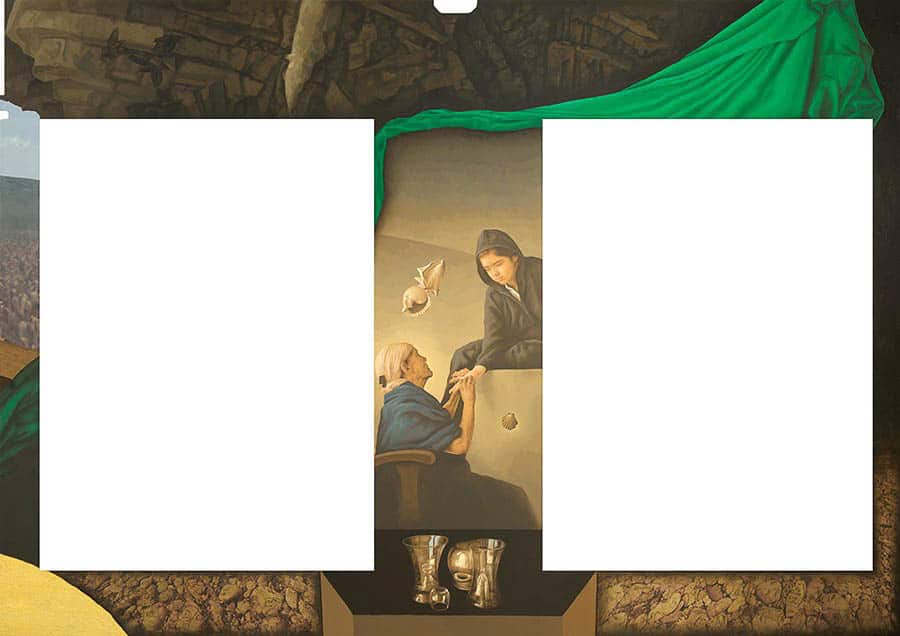

Santiago Carbonell Paths of words and silences, of men and women, of memories and forgetfulness (detail Grandmother and girl) 2010 mural, Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, Mexico City.

Also featuring green is the scene Grandmother and girl in which shells float between the two women, suggesting shamanistic prediction, transformation and alchemy (two windows are omitted in this reproduction). Like obsidian, abalone shell with its reflective nacre was often carved into discs and worn as pectorals. This prehispanic talisman also signified the jaguar, Tezcatlipoca.

Santiago Carbonell Paths of words and silences, of men and women, of memories and forgetfulness (detail Sacrifice) 2010 mural, Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, Mexico City.

A reflective gold disc akin to the sun or an eye seems to peer over the scene entitled Sacrifice in which a shamanistic figure looks over a dead body resembling Che Guevara or Christ above the inscription “Yo soy” (“I am”). While white traditionally denotes Catholic purity, here it points to the violence and spread of colonisation and to the war on drugs. The latter began in December 2006 when newly elected President Felipe Calderón sent 6000 soldiers, marines and federal police to his native state of Michoacan to combat the drug trade, drug-related violence, and the rising influence of drug cartels, resulting in widespread bloodshed. Sharp lines of expressive red paint are ‘shed’ over this mural and carry over space onto the next wall in violent applications suggesting the lethality index of an exceptionally violent military and rogue cartels. Carbonell’s hyperrealism is one that conveys imagery with precision. Figures are pulsating with life or death—the death of blood spurting from a wound.

An actual mirror appears in Mirror of justice, where blood spatter arcs across the surface of three women depicted as serene, classic beauties holding mirror-like discs. Yet, their idealised figures do not mirror an idealised state of affairs—they appear objectified as furniture. An actual circular convex mirror (invisible in reproduction) is installed as if being held by one of the female nudes. When we look in the glass and see our reflection we are implicated in the scene of her nudity—the blood splattered across her and the pre-Columbian landscape pictured behind her are second to her body.

Santiago Carbonell Paths of words and silences, of men and women, of memories and forgetfulness (detail Mirror of justice) 2010 mural, Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, Mexico City.

The entire mural may appear completely painted at first, but upon closer inspection is in part composed of prints—large photographic reproductions of distant masses of Mexican peasantry and industrial working class, corn fields and Aztec landscapes. The prints are layered with a thick, textured, transparent medium in which text, describing attributes of justice and injustice, has been inscribed, creating shiny relief. Yet, perhaps the easy combination of texture and photographic print detracts from the seductive quality of the clear line and bright colour in which the painted figures are conveyed. Notwithstanding this aesthetic criticism, the large-scale printing of the scenes denotes a collective memory of sorts that draws the observer’s mind into the archives of history.

The archive is also invoked by a part of the mural featuring an artist peering out from behind a canvas. As if painting the viewer, or painting a mirror image of himself, or perhaps something we cannot see, Carbonell seems to be referencing Velázquez’s Las Meninas, a painting in which the viewer is famously apprehended by the painter’s look. In Carbonell’s work, the artist appears as a reflexive allusion to mirroring, providing a metathesis of visibility and self-knowledge. More allusions of mirroring occur through the use of trompe l’oeil. The scene is punctured by a series of actual doorways and windows spanning floor to ceiling. This incorporation of the architecture of the building (also omitted in these reproductions) plays with illusionism. A photographer is positioned beside the painter—both figures chronicle reality while the tools of the worker are portrayed at a 1:1 scale, further reinforcing the trompe l’oeil trope. The play with illusionism, photography and painting causes us to question what is truth and what is illusion. Together these references to Western painting, artistic agency and awareness of audience seem to sit uneasily with the state patronage that had sponsored the mural.

Santiago Carbonell Paths of words and silences, of men and women, of memories and forgetfulness (detail Painter and photographer) 2010 mural, Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, Mexico City.

By deconstructing the relationship between these modes of representation, Carbonell nods to the deconstruction of Western modes of seeing and knowing. Whether this further connotes projects of decolonisation is another question, but he does give voice to people who have been silenced or overlooked. However, does this imagery, supported by the walls of the court—itself a site of European cultural imperialism—present a utopian vision of a social structure changed from the bottom up? In Mexican culture, walls have always been rallying points for the people—walls mythically connecting heaven and earth such as depictions of the Great Goddess of rain found in murals at the ancient city of Teotihuacan. Through prehispanic references and images of colonised subjects, the mural might connect a pantheist spirit of the past with the revolutionary spirit of a people in need of justice. Yet, in spite of their realism, and maybe even because of it, there’s something ineffective about the figures’ congealed realistic synthesis. Their passive faces and contrived poses hardly suggest the cry of the real social conditions of uneven wealth. Tucked away in the interior of court-sponsored walls, I see it as something of a mural of hypocrisy: an idealised state of affairs that aestheticises the insecurity and insufficiency of the Mexican justice system through technical skill and posed solidarity.

All images from Santiago Carbonell’s website: http://www.santiagocarbonell.com/new/#!/mural-2/

Content for ‘The dark glow of the mirror’ was originally presented as part of the 2017 LSA Conference in Mexico City, Walls, Borders, and Bridges: Law and Society in an Inter-Connected World, in which Desmond Manderson, Australian National University,Luis Gomez Romero, University of Wollongong and Madeleine Kelly, University of Wollongong, led groups in situ at the Supreme Court of Justice, Mexico City, exploring the theme ‘Justice and the Art of the Wall: The Politics of Mexican Muralism’. Manderson and Gomez spoke respectively about Rafael Cauduro and José Clemente Orozco and Kelly spoke about Santiago Carbonell. Thank you to Nan Seuffert, Director, Legal Intersections Research Centre, University of Wollongong, for your support.

Author

Madeleine Kelly is a visual artist and lecturer at Sydney College of the Arts, The University of Sydney. Her creative work explores the materiality of images, in particular painting, by depicting protean and rubric worlds. She is a full-time painting lecturer at the University of Wollongong and is currently working towards an exhibition at c3 Contemporary Art Space, Abbotsford Convent, Victoria. Her work can be found at www.madeleinekelly.com.au

Madeleine Kelly is a visual artist and lecturer at Sydney College of the Arts, The University of Sydney. Her creative work explores the materiality of images, in particular painting, by depicting protean and rubric worlds. She is a full-time painting lecturer at the University of Wollongong and is currently working towards an exhibition at c3 Contemporary Art Space, Abbotsford Convent, Victoria. Her work can be found at www.madeleinekelly.com.au

Further reading

‘Cauduro’s Crimes’ in Desmond Manderson, Temporalities of Law in the Visual Arts,Cambridge University Press, 2018.