Lazaro Monjaraz’ father would trek two days on foot from the remote village of Yutanduchi de Guerrero, over arid palm laden hills, across rivers, up arboreal peaks of almost 3000 meters and finally down to the central valley of Oaxaca to the village of Atzompa where he would purchase the new clay pots he needed for distilling mezcal.

On the long journey back he would carry one pot on his back with the help of an ixtle-strap synched tightly across his forehead. His burro could carry two pots, but as burros do, would on occasion decide enough was enough and lay down abruptly, breaking the precious cargo. People in this region are no stranger to arduous hikes. This part of Oaxaca lies directly in the path of the old Camino Real that linked Guatemala to Tenochtitlan, by which fresh ingredients where portered daily to the Aztec kings. Gone are the days of walking to Oaxaca, but Hacha as he is known by friends, still rarely makes the four-hour car ride into town, ”hay demasiado trabajo”. I have enjoyed Hacha’s delicious Papalométl mezcal for some time and was happy to comply with his request that I bring him a new olla the next time I came to visit. Hacha had been using the cheap and durable metal tamale pots for the bottom of his still with only the top pot being made of clay, but wanted to return to the traditional way of distilling using clay for the bottom pot as well.

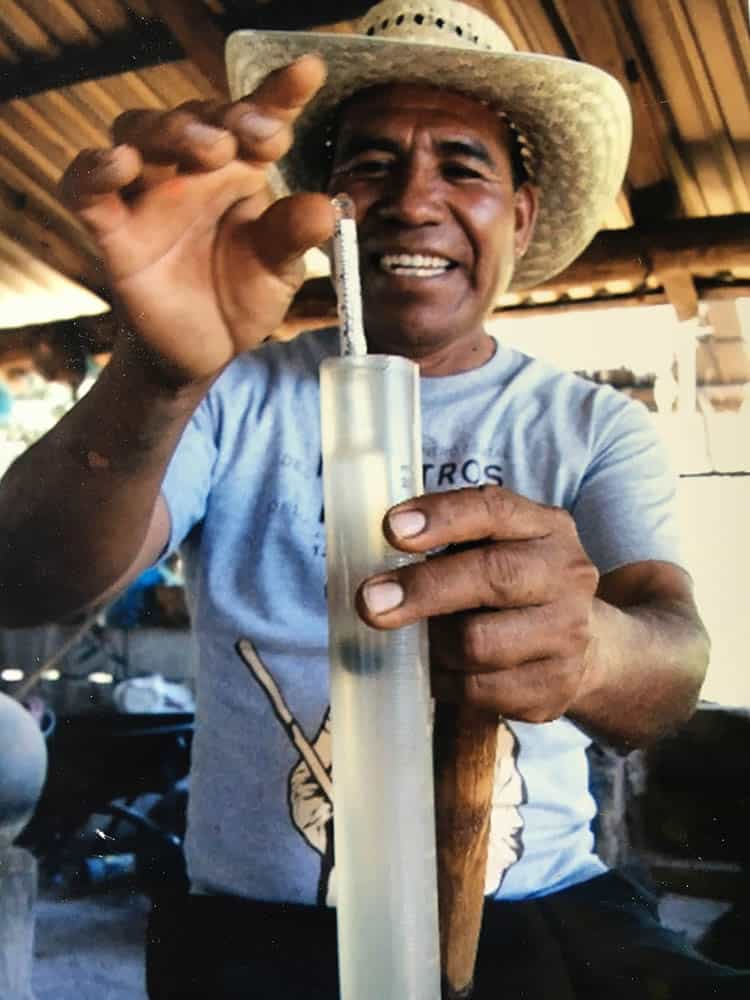

As requested I went to Atzompa in search of a proper pot for distillation. Enter Margarita Juana Lara Vasquez, olla producer extraordinaire. Margarita’s family has been working with clay for as many generations as she can remember, but it wasn’t until 27 years ago when she married that her father in law taught her the art of making the large clay pots needed for mezcal distillation. These days Margarita works almost exclusively on these special pots and intricately carved oversized earns.

The history of mezcal production in Mexico is a hotly debated topic with some arguing that its production arose with the introduction of stills by the Spanish or Filipinos, and others that distillation was actually pre-hispanic. While there is definite evidence of the cooking of agave and the consumption of its fermented juices throughout what is now the Southwestern US and Mexico, there is no conclusive evidence that these juices were distilled. It has been demonstrated that distillation could have been done using vessels found at archeological sites, but we still lack chemical-residual evidence that distillation took place. It is possible that distillation was unknown to the Native Americans or simply that all evidence has been erased due to wear overtime on this relatively delicate clay. The prehispanic peoples certainly had the means to make a distillate with all the clay and agave present in Oaxaca. Regardless of the exact date of the beginning of mezcal production, we know people have been making clay vessels in Atzompa since it was founded in the seventh century. When pressing for any specific date or hard evidence as to when the first pots for distillation were made, all I was told is that they have made ceramics in Atzompa for as long as anyone can remember. People are quick to remind me that the library and church have burnt down a number of times in this town where fire plays such an important role; written accounts are hard to come by.

There are curious similarities to the processes of making an olla for distillation and making mezcal. Both are toilsome endeavours that require significant physical labour and large amounts of fire and heat. First one must acquire the Material-Prima. In the case of clay production in Atzompa two types of clay are mixed to make the desired starting material. A black, wet clay is mined onsite at the “Laguna” in Atzompa and a higher-grade version of the black clay is bought from the nearby village of San Felipe, while the white, dry clay is bought from a mine in San Lorenzo. Mining for clay is hard, time-consuming labour and many people prefer to save the time and energy and buy the clay from others who assume this work. The same is seen with mezcal producers; as increased demand pushes them to search further and wider for new agave sources, they often buy agave from other communities, a practice while by no means new is nonetheless becoming more prevalent. Like the Clay Miners with the Pot Makers, the Pot Makers with the Mezcaleros, and the Mezcaleros with the Magueyeros, these are relationships that undoubtedly span hundreds of years, one family’s work relying on the other’s in a beautiful, yet simple chain that remains to this day.

In Lalo Angeles’ Palenque in Santa Catarina Minas, all the cooked agave is being smashed by hand using large wooden mortars, a requirement for the category “Mezcal Ancestral” as per the new NOM-070. As the agave is macerated so must be the clay. Don Miguel Pedro Garcia Mendez, whose family has been supplying Lalo’s family with clay pots for as long of either of them can remember, also uses a wooden pole to beat the white clay into a sandy texture. Margarita, Don Mendez’ Daughter in law explained to me that the size and texture of the white clay is very important, that the ollas for mezcal should be made with a grittier-textured clay, affording them stronger resistance to the constant stress of being heated and loaded with agave and liquid, while the beautiful earns she makes require a smoother, finer grind of clay.

As Lalo’s process is almost exactly as his great grandfather’s was, so is Margarita’s. She assures me that the only real changes in clay production have been the small-bearing-aided platform she sets her pots on, allowing easier rotation, which was traditionally done on an inverted-shallow-bowl and the arrival of plastic tools used for shaping and smoothing the clay which were formerly made of gourds. Another thing that has probably changed over time is the esmalte or glaze. Atzompa is known for its green glaze which was actually introduced in the sixteenth century. Likely before this, the pots were unglazed, as they are still made in many parts of Oaxaca. In the 1990’s concerns over lead found in the glaze prompted US authorities to restrict Mexican ceramic imports leading the Mexican government to develop a lead-free glaze which is used in Atzompa today.

Both mezcal producers and pot-makers whose jobs are so closely tied to the earth are always at the mercy of the weather. Water dilutes sugar concentration in agave, wets clay, cools ovens and puts out fires. The ambient temperature can help or hinder fermentation, the efficiency of an oven or the curing of clay. There is a prime season for making mezcal. At the end of the dry season, agave sugars are most concentrated, and the temperature is starting to heat up allowing for fast and stable fermentations. Rain is yet to fall, corn is yet to be planted, and there is time. In the case of the pot-maker, hot wind and rain are her enemies. If it is too hot out and the wind is blowing, the clay can dry too fast and crack and crumble before it is ready to fire. Likewise, rain will put out your oven and turn your clay back to earth. Both mezcal producer and pot maker always have an eye on the sky, rushing to get things in before rain, shifting spaces, covering and uncovering as the weather dictates.

The oven is an essential part of making a good mezcal or a good pot. If you think it’s just getting something really hot, then throw in the potatoes, you are quite wrong. In both cases, it is truly an art knowing how to arrange your oven so everything is cooked evenly, nothing raw, nothing burned. Undercooked agave won’t yield as much sugar or flavour, burnt agave will have people calling mezcal “tequila’s smokey cousin”; both highly undesirable outcomes. An over-fired clay pot will warp like a piece of plastic thrown in the fire, and an undercooked clay pot will just be more clay and less pot. Ovens require heat, which in both these cases means burning a lot of wood. Agave hearts are baked once, and then the juices are cooked again in the distillation. Clay pots in Atzompa are fired once they are cured to harden them, then go through a second hotter firing of 1000+ C to set the famous green glaze. As wood is either collected by hand or purchased, it is another time and money consuming necessity for mezcal producer and pot-maker alike.

The importance of the oven in both the production of mezcal and clay pots is highlighted by the various superstitions surrounding it. If you have even been to a palenque (traditional mezcal distillery) in Oaxaca you have probably seen a small cross placed on top of the oven mound, most producers being of the Catholic faith. Curiously enough, the Mescalero Apache of the US southwest were also observed drawing a cross on top of their horno and one wonders if today’s tradition may have more pagan roots. Modern-day mezcal producers share another tradition with the Mescalero Apache; that of varying levels of prohibition of women going near the oven. I have also heard this superstition repeated in respect to barbacoa ovens, the traditional underground method of cooking meat seen throughout Mexico. Don Garcia Mendez does not adhere to this superstition, all hands are welcome in his horno, his main disciple being his daughter in law, Margarita. He does however always set a cross in his horno, sprinkle holy water around and recite a special prayer before every firing asking that everything comes out well cooked. If disaster does strike the horno with a pot breaking or bending during firing, it is believed that the pot has taken on misfortunes that may have fallen upon the pot-maker herself. A curious mix of Catholic superstition and indigenous beliefs that undoubtedly precede the Spanish conquest live on in a uniquely Mexican way, and as he looks above Don Garcia Mendez assures me that firing around a full moon will yield better product, a belief shared by mezcal producers throughout Oaxaca. “Cuando la luna es maciza, las ollas también”.

While mezcal production in Oaxaca has exploded over the past decade in response to mezcal’s new-found popularity in Mexico and abroad, most of this mezcal is distilled in copper stills. There was a long period in Oaxacan history where clay-pot distillation was by far the most common due to easy access to the material and the relatively low start-up cost of purchasing a few ollas. Mezcal was also originally stored in near-water-tight clay vessels called cantaros, a rare sight today. Clay pots have a smaller capacity, are harder to heat and seal, and are bound to break at some point; leading to an overall inefficiency in both cost and mezcal yield. Being much more efficient and cheaper to maintain, copper-stills have taken a hold in most communities that produce commercial quantities of mezcal.

Making clay pots for distillation is hard, time-consuming work with a relatively large initial investment and small profit margins. Margarita seems unsure if her children will continue the tradition, and Don Garcia Mendez assures me that there are only a few families that still know how to do this work. Mezcal continues to gain popularity worldwide and there is a large contingent of academics, producers, and mezcal-lovers that are fighting to keep this distillate from going the way of it’s now industrially produced cousin, tequila. In Sola de Vega, the Mixteca Alta and Santa Catarina Minas clay pots are still the principal means of distillation, a tradition that is now recognized by a separate class “Mezcal Ancestral” in the Mexican law that governs mezcal production. One hopes people like Lalo Angeles and Lazaro Monjaraz who are dedicating their lives to maintaining this traditional method of mezcal production, will, in turn, keep alive the traditions of the clay miners and pot makers in Atzompa for many generations to come.

Author

I live most of the time in Oaxaca, Mexico and have been working closely with the Civil Association Maestros del Mezcal for a number of years lending a hand wherever I can. In August I will be importing into the USA the first lots of the Cuish brand of Mezcal through my Imports Company, Of Spine and Vine, LLC. Cuish is owned by Felix Hernandez Monterrosa, who has supported Maestros del Mezcal AC throughout the years and who works with some of the members of the association. I recently launched the Maestros del Mezcal AC podcast with the intention of spreading more in-depth knowledge about traditional mezcal.

I live most of the time in Oaxaca, Mexico and have been working closely with the Civil Association Maestros del Mezcal for a number of years lending a hand wherever I can. In August I will be importing into the USA the first lots of the Cuish brand of Mezcal through my Imports Company, Of Spine and Vine, LLC. Cuish is owned by Felix Hernandez Monterrosa, who has supported Maestros del Mezcal AC throughout the years and who works with some of the members of the association. I recently launched the Maestros del Mezcal AC podcast with the intention of spreading more in-depth knowledge about traditional mezcal.