I’ve always been drawn to the warmth of the Indonesian people and the richness and diversity of culture. The climate agrees with me very well also. Certainly, the more familiar the place gets, the more warmly welcomed you feel and more homely it becomes. I was first drawn there in the mid-80s for the already popular Bali holiday, and have been a visitor ever since. I remember hanging out with this guy from Perth who was commissioning locals to produce handmade embossed copper sheet artworks of America Cup yachts at the time. I was taken by his venture, and all the other local craft I had seen.

Soon you learn that all this cultural and ethnic craft in the art and antique shops around Legian and Ubud is rich to a particular part of the archipelago. So 20 years ago I set out to visit the craft producing villages, craft families and craftsmen in Nusa Tenggara, starting in Lombok. Like everywhere I suppose, you would still find plenty of merchants sitting on stockpiles of primitive themed craft, but for me being the visitor to the source was adding the extra intimacy to the craft process.

For a while, I was doing some batik shirts with Ketut Slo at Sama Sama in Ubud. She was still able to order the old Baliku style of batik which I’d aspired to re-create, and the results were great. However, I was just ordering shirts and seeing what came about, not really involved in the process which lacked a bit of substance for me. Everything changed whilst accompanying Kevin Murray to Central Java on the Dialog Batik trip a few years back, and also gaining the respect and understanding of the Sangam Project. After immersing ourselves in the batik process and the batik workshops in Semarang and Pekalongan, I was starting to get a liking to the smell of burning wax and wanted to experiment with it. So through being a visitor and some trial and error, I have been able to commission batik.

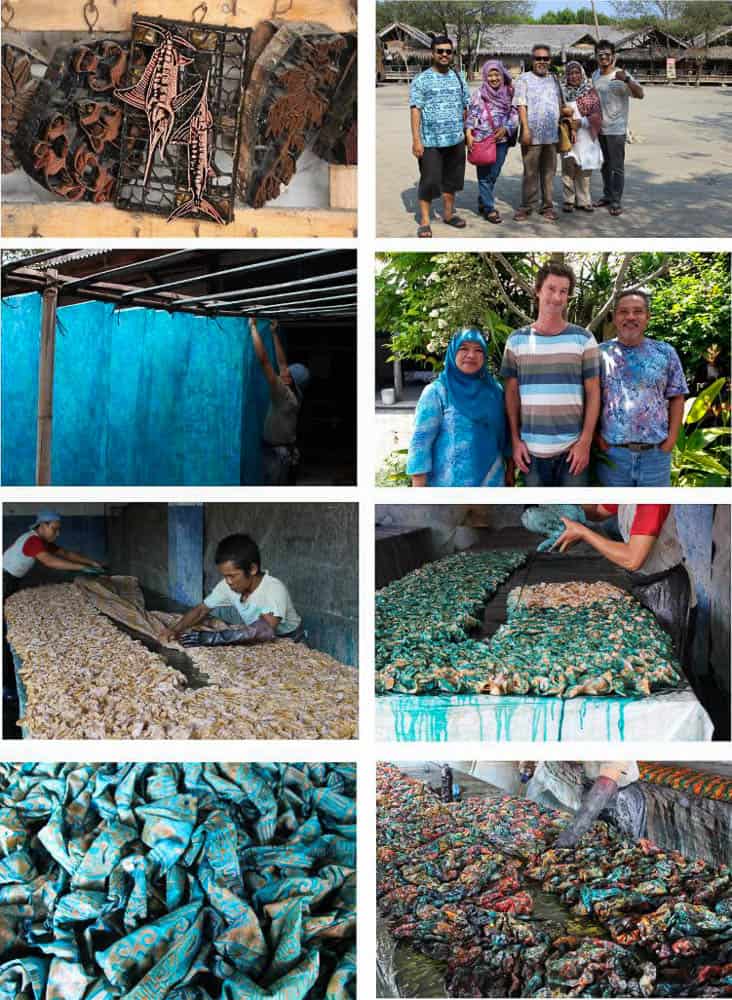

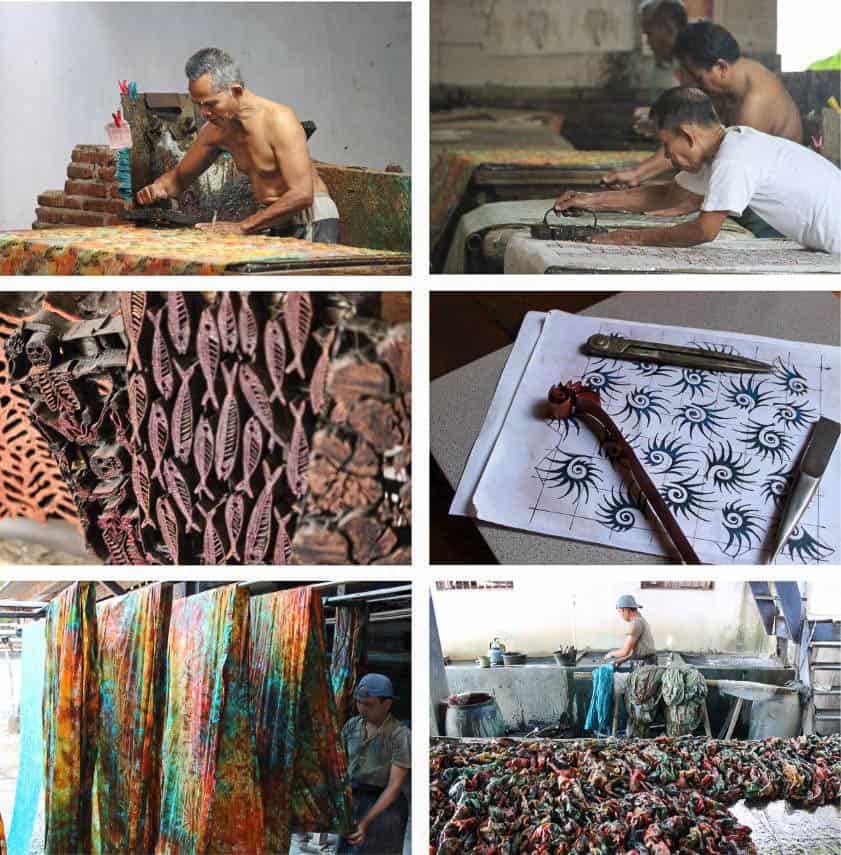

Made is the name of the founder of ASA Batik (pronounced Mar Day). ASA Batik is a workshop I was introduced to by Zahir Widadi, who was our fine host on the Sangam trip and the director of batik at the local University in Pekalongan. I owe it to him for sharing my vision and recommending I go visit. I met with Made Wiasa, the founder of the workshop and originally from Bali. He had moved up to the north coast of Java and decided to stay. We had a nostalgic chat about Bali and he showed me around. They had been doing some export to the U.S. many years earlier and they had an interesting array of less traditional type copper stamps (caps) because of this era. Unless you commission a particular design cap to be produced for you, it’s going to get pretty daunting trying to find something in the absolute abundance of existing designs. The cap is the masterpiece within the batik process and batik workshops are their gallery. So my idea was to dust a few down, get some copper shine back into them, then bring them back to life onto some shirts for the Aussie patrons back home.

Is it worth noting that the Javanese are Muslim, and so have fewer distractions? They have no God imagery as such, nor do they have all the ornate decoration and ceremony of the Hindu Balinese.

It’s like the Balinese are the designer/artists, and the Javanese produce it by hand with an artistry of accuracy in their design, almost machine like. It’s the mathematical way of Islam that has everything so well measured. Like mosaicking a mosque. Or repetitively hand carving lava stone statues all identical. Without these measured formulas, I would have struggled to create the foundation for elephant shark. Because I’m so full of distraction myself.

I certainly wanted to do something that would bring about some results from our original trip. Something that really mattered was the Sangam Code of Practice for the project: the foreign designer working with artisan, with traditional craft techniques for a broader market, and the ethical way of going about it. Knowing I had a few platforms back home to make it sustainable and see how it would be received, inspired me to put it out there and have a go.

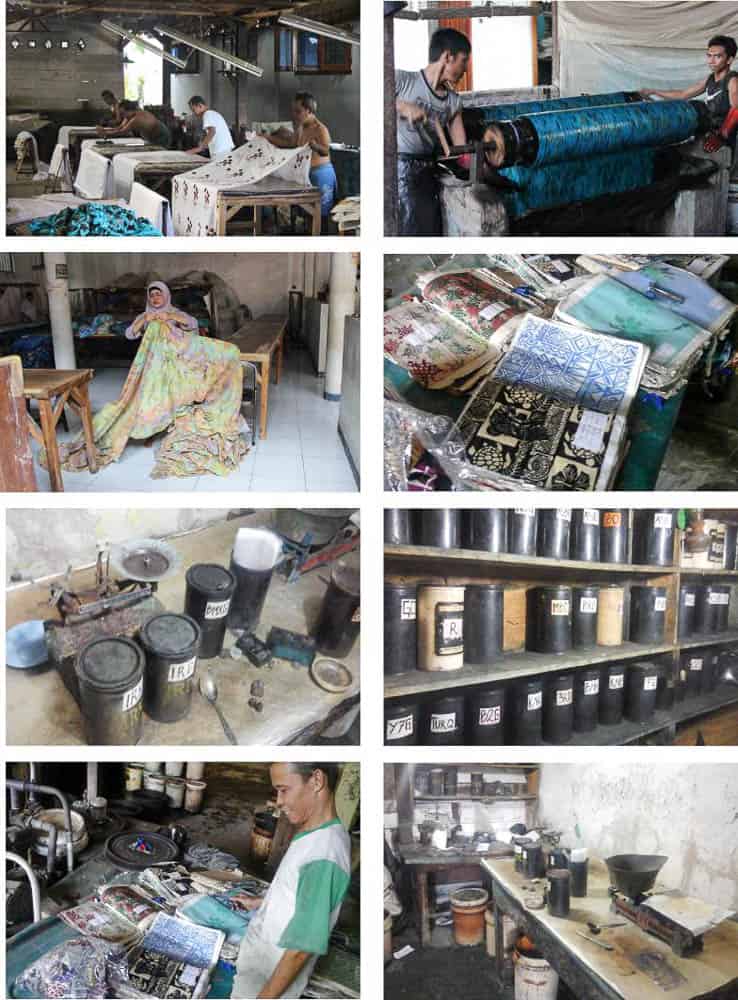

The production process

To arrange an order with Made I first needed to find out the minimum quantity of each design he required and agree to a price on that quantity.

I call this the “sample quantity”, just because I wasn’t hanging around to oversee the whole production process, and so the result once I received it in Melbourne some months later was still largely experimental. Ten pieces of each were agreed over a breakdown on sizes. Finally, a deposit is essential to get the ball rolling in Indonesia. I’ve always been a believer of having to wear the cost of samples, especially if they don’t lead to an order for the artisan.

It seems the Javanese are brilliant at keeping this code system in place for every detail. This helps enormously to relay design information. They have a code or name for each stamp and an extremely thorough and extensive note on all their past jobs. I’m sure they know how crucial this is when it comes to reordering. I’m impressed with the colour combination codes, as it’s all done with a weighted measurement of powdered pigment in the colour lab.

After rolling the dice a few years with this project, I have also been able to design new ideas on the computer and arrange it from home. Mixing up the existing codes and changing them around a bit to see what comes about. It’s a never ending story I hope.

The stamps I decided on from the outset were all ethnic or primitive in their design. The generic t-shirt came alive with a primitive design element and an ethnic process to match. The style was actually quite fashionable at the time with lots of ikat and Aztec prints appearing on everything. And later that would lead to some interesting product testing on the masses.

Most workshops having a great array of swatches from their past production. These are a great way to get a visual on some past results and combinations. During some sampling at Tobal batik in Pekalongan, I came across this wonderful mystical half fish, half elephant cap which led to the project’s name and logo.

And the name? Many years ago while out fishing near Phillip Island I caught an elephant shark. At first, I was like “What the hell is that ?” My mate informed me what it was, and that’s the only reason I even know they existed.

It seemed too exquisite looking to keep, so I let it go. But I’ll never forget its appearance and the surprise it gave me when it arrived on the side of the small boat we were in.

The Elephant Shark product was introduced into a hyper commercial retail world of the tourist centre Phillip Island, as a micro project trying to relay its point of difference from one island folk to the next. But really it was just me trying to create a concept from a time in the past that I had known in Indonesia, when the art shops, markets and galleries ruled the streets. It was a time before foreign corporate branding hit the shores. And only the branding of an artist’s impression into a batik stamp adorns the merchandise.

Perhaps it’s the fearsome shark that we need to catch or control that adorned the sarong for the beach in Bali. Or it’s the beloved and worshipped elephant god branded on our shawl for the temple ceremony in India. It’s wearable artisanal art, with a story to tell, branded by a process called batik.

Author

Marty Hope lives in the Upper Yarra Valley in Melbourne with his partner Rochelle. After coming from a sign writing, display and visual merchandising background, he opened the Pipal Tree store in the Dandenong Ranges around ten years ago, which is still running today. Since then, he has been sourcing and developing product in Nepal, Thailand and Indonesia for the various Pipal Tree retail platforms. He would love to establish a mobile batik workshop in Australia.