Francisco Huichaqueo, 2015, Photo provided by the MAVI museum

Lucía Nieves Cortés interviews Mapuche video artist Francisco Huichaqueo about his challenge to evoke the spirit of objects captured in a museum

(A message to the reader from Francisco Huichaqueo.)

In 2015 The Visual Arts Museum of Santiago (MAVI in Spanish), invited Mapuche video artist Francisco Huichaqueo, to curate and renovate its Archaeological Museum gallery (MAS in Spanish). The MAS has its own collection of over 3000 pre-Columbian art objects and it works in close collaboration with the Chilean Pre-columbian Art Museum (Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino). Initially, Huichaqueo resisted. He felt that his experience as a contemporary artist did not suffice to face the responsibility of representing his Mapuche Nation and handling the ancient craft objects of a powerful culture that is alive and, as many other First Nations worldwide, engaged in a struggle against the State that even today makes headlines.

In this interview we speak with the artist about how he overcame the challenge of being the first member of the Mapuche Nation in Chile to curate such a space for a prestigious museum and about the lessons he learned throughout the process, thereby making a contribution to both his colonized nation and to the practice of archaeological museology in the treatment of expropriated cultural and spiritual heritage. He considers Wenu Pelón to be not just an exhibition space but a space of dialogue and repair, as well as a spiritual mission and not just a project.

What was your link to the MAVI and why did they approach you with their proposal?

The museum´s authorities at the time, director Ana Maria Yaconi Santa Cruz and museum´s general curator Maria Irene Alcalde, met with me to talk about a renovation of their archaeological exhibit. The MAS raised little interest in the MAVI´s audiences, who identified the museum with contemporary art but not with archaeology. They had a well-presented exhibit, but it lacked a vital dynamic, it was an outdated curiosity cabinet. My link to the museum was in a very different context. I had previously shown my work there during the Chilean Triennial and co-curated, together with artist Maria José Rojas, also an important work partner for Wenu Pelón, a series of contemporary video art screenings. They knew that my own work was devoted to issues concerning First Nations, especially my own, the Mapuche people and that led them to me for the job.

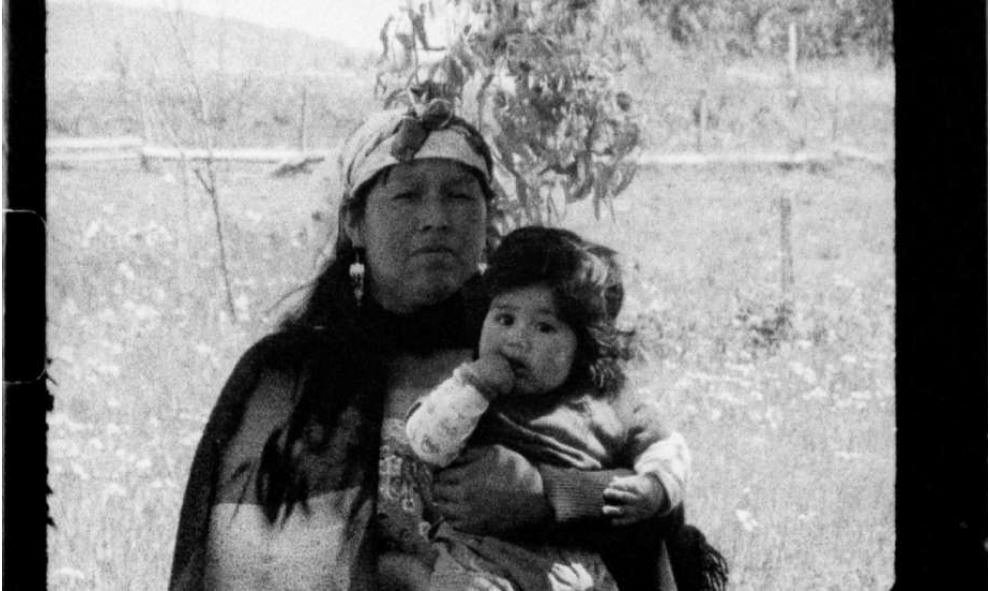

- Francisco Huichaqueo, film stills, 2015, Photo by Fransico Huichaqueo

- Francisco Huichaqueo, film stills, 2015, Photo by Fransico Huichaqueo

- Francisco Huichaqueo, film stills, 2015, Photo by Fransico Huichaqueo

What were your first thoughts and reactions to their proposal?

At first, I was reluctant and declined to participate, I had no experience in this particular field. It seemed an enormous responsibility and I was worried about how the Mapuche community would judge my participation. But the museum kept insisting and I began to wonder whether this request had crossed my path for a larger reason that should not be turned down.

You see, in our culture, when someone receives a calling and refuses to comply, she or he will be beleaguered by all sorts of malaise, even death. I wanted to be sure about whether it would be sensitive towards our codes of cosmovision, so I discussed the matter with José Ancán and he pointed me towards Juana Paillalef, director of the Mapuche Museum in Cañete, who had ample experience in the matter.

When she began work in the Museum in 2010, the exhibit corresponded to conservative Western thought. Under the guidance of the communities and their spiritual authorities, including Mapuche poet Leonel Lienlaf, she led a complete renovation of the space and its surroundings, turning them into a cultural and spiritual house that reflects and serves an active culture, without neglecting its objectives as a museum for larger audiences. The process was riddled with incomprehensible occurrences, such as objects disappearing and later reappearing in closed and guarded boxes. They had to go to great lengths to adjust to Mapuche codes of cosmovision, which are very much outside the paradigms of museology.

We met in Cañete and shared a very intimate conversation. Juana provided me with an in-depth look at their experience: it was not just what she said, but also the many gestures outside of language that transpired that day. For example, before we entered the space where the Kalku Stone, a power stone, is housed, she paused and carried out a llellipun or prayer. She embodied an attitude of respect. I could feel my whole body become an immense eye which absorbed this exchange. I still was wary about accepting the call, but at the end of the day Juana was convinced and advised me to engage the spiritual aid of a Machi. What I learned that day became a fundamental part of the guiding principles of what I began to call a spiritual mission and not a project.

What followed?

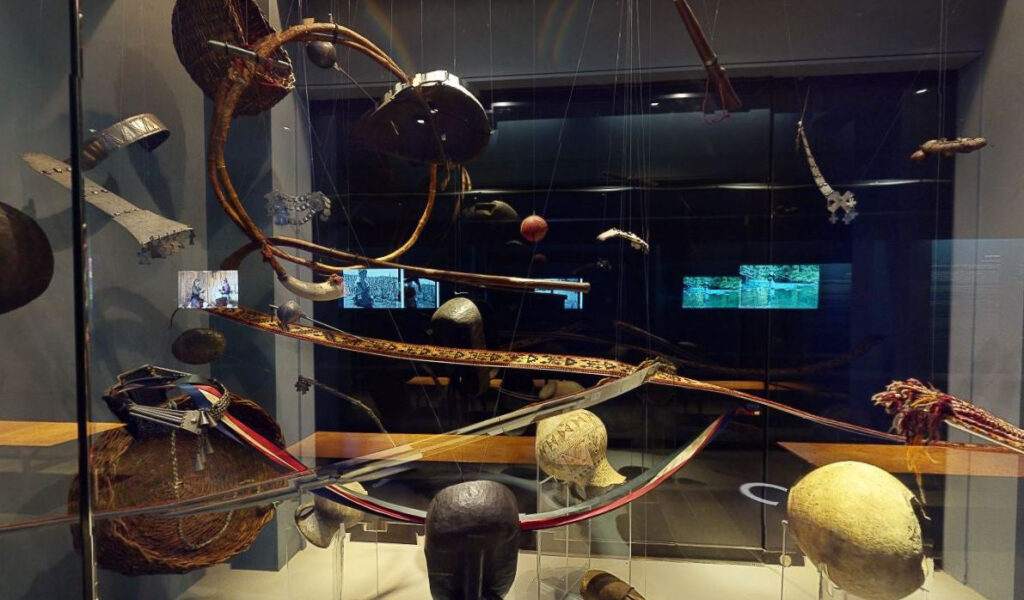

Before my bus back to Santiago, deep exhaustion flooded me. I decided to find a hotel room to rest, and there I had a peuma, a dream vision. I saw my spirit hover through the sky and found myself in a dark and vast room. I heard a sweet elderly voice call out my name twice. Mapuche objects surrounded me, floating in space at different speeds. Intuitively my spirit entered a metawe, a clay pot. Once inside I could see projection-like images in black and white of people I knew from the Mapuche communities carrying about their daily life activities. I remember entering maybe four pots with different moving images. Shortly before the dream ended light pierced the ceiling and flowed into the space, the objects floated out through the opening one by one. This peuma would later become the guiding concept and gave the exhibition its name: Wenu Pelón, portal of light. There was no need to look elsewhere for ideas.

Those two events provided the necessary information to guide the project…

The basics, yes. Once back in Santiago, the people of the MAVI were eager to know what had happened and when we could start to work, there were only two months left until the opening date. I had to explain that this was now a spiritual mission, and that to begin, we had to wait until I was visited by a peuma.

At first, I held back about my dream and the many ones that followed, I was not certain that the definitive peuma had yet come. Meanwhile, I contacted Machi Silvia Kalfuman and after long conversations, she accepted to be my guide. We had to wait for her permission to move forward and at the museum, they were getting nervous.

Ana Maria Yaconi was very supportive throughout the process, even though they did not quite understand what was going on. This was not contemporary art, this was not archaeology, this was something else, outside of their paradigms. After many days of daily rituals, Machi Silvia was also visited by a peuma, a confirmation that the mission had been blessed and approved and she requested me to take her to the museum, to see the objects. She had never been there.

A week later we were received at the archives of the Chilean Pre-columbian Art Museum. There, dressed in full ceremonial attire and holding her kultrün drum ready, she requested to see all the objects. The museum officials and expert museologists were baffled. The collection was too extensive, some 1400 objects, so instead they brought out examples representing the various object categories.

- Francisco Huichaqueo, Rogativa on opening day, 2015, Photo provided by the MAVI museum

- Francisco Huichaqueo, Rogativa on opening day, 2015, Photo provided by the MAVI museum

Machi Silvia began a rogativa, a ritual, by playing the kultrün. She asked me to accompany her with a pifilca flute, but I had not brought mine with me! “Take one from the table” she declared. The staff jumped in terror, “don´t touch it, you might contaminate it” they answered. But she did not back down “Contaminate? Nonsense, these objects belong to our ancestors, our people!”. A Machi is the highest spiritual authority, she had the last word. I played a pifilca that had not been used in perhaps 150 years. At first its sound was dry, but it suddenly blasted out in full potency, coming back to life.

After performing the ritual, the Machi wished to visit the Museum upstairs. As she walked around playing the kultrün. museum visitors stood in awe, and all the while she questioned the ways and positions in which the chemamull statues were hanged for exhibition, correcting the museum authorities.

A powerful experience!

Yes, from this moment on, things started to pick up their pace, much to the relief of the MAVI staff. Still, they were wondering what the exhibition was going to look like. I finally presented a drawing of my peuma, the exhibition concept, a darkened space in which the objects would be “floating” towards the light. I declined working with the museum experts and brought in my own team for set up.

- Francisco Huichaqueo, View of Wenu Pelon, 2020, Screenshot from 3d virtual tour provided by the MAVI museum

- Francisco Huichaqueo, View of Wenu Pelon, 2020, Screenshot from 3d virtual tour provided by the MAVI museum

- Francisco Huichaqueo, View of Wenu Pelon, 2015, Photo by Fernando Melo

The exhibition is a showcase of ancient objects and videos of your own making, how did you choose the pieces?

We selected among different object categories: clay metawes, silver jewelry, wooden kollón masks, baskets, woven trariwe belts which represent an individual´s lineage, wooden palín sticks for sport and martial training, instruments and others. Only things of daily life, no ceremonial or ritual objects, except for a powerful kultrün. The Machi had the final word on that matter, too. There are no labels, no names, no dates. Only the objects floating in space, as if trying to return to Wenu Mapu, back home, through the portal of light.

Would you say the selection portrays Mapuche daily life?

Yes, you could, something meaningful from every element of life, coupled with the videos. I contacted communities to produce the film material. It was not easy, but in the end I was allowed to film where I least expected to…

These communities are in a heated struggle for land recovery….

Exactly, and I was received at Wente Winkul Mapu, thanks to its werkén, chief and spokesperson, Daniel Melinao. A community where no cameras had been allowed before. Melinao was a political prisoner, fighting to stop the militarisation of Mapuche territory. We had a long discussion and he raised a lot of questions, but finally allowed me to film.

Tell me about the videos.

I documented daily life activities such as weaving women, the fields, children, Melinao on horseback.

A video shows a horse and a kultrün…

Horses are important spiritual bridges in Mapuche culture, not tools. This specific film was inspired by the peumas of Machi Silvia. There are a total of seven videos, two of which are projected inside metawes.

…like in your dream…

Exactly.

Wenu Pelón is more than just an exhibition space, it is also a space for trawünes, reunions.

The space is meant as an opportunity for dialogue, to reunite our and other cultures. A bridge between Mapuche and Chileans and a space moved by ancestral energies.

The space has hosted a series of events. Can you mention some of them?

Each event held there has been inspired by a peuma that has visited me. For instance, I saw artist Cecilia Vicuña holding a red thread in a dream that led me to invite her. She spoke about the red thread as a symbol that unites Latin American women. There was a reunion of poetry and another for ritual dances. Other Indigenous artists have been there to show their work and join the ongoing conversation. For example, film-maker Alanis Obomsawin, of the Abenaki Nation, whom I met at a First Nations film festival in Canada.

Wenu Pelón was initially planned to be two years on display, but it has stayed.

Yes, the museum officials have played a key role in defending the permanence of the space as it now is. The Archaeological Museum is no more, it is now something else.

On the opening day, I was visited by the vision of an elder, I even believe that was the day that Lautaro passed away. It is a space where many people have been moved by powerful experiences. It is a space to heal colonial wounds. It has its own life now. It is Mapuche territory. Every step of the way has brought its lessons. For me, it has been an immense gift.

✿

Wenu Pelón, Portal of Light is currently on permanent display on the second floor of the Museo de Artes Visuales de Santiago. To make it available despite COVID restrictions it is now also available as a 3D virtual tour, the link is provided below.

Huichaqueo recently participated in the 11th Berlin Biennale for contemporary art, with a compact version of Wenu Pelón that includes his film material as well Mapuche objects provided by the Ethnological Museum of Berlin. Another version was presented in De-celerate in New Zealand, featuring a video projected within a metawe made by local artist Stevei Houkāmau.

Links

Museo Pre-Colombino website

Kulmapu, Includes an interview with Fransisco Huichaqueo, subtitles in English

Further Reading (suggested by the artist)

Lienlaf, Lionel. Epu Zuam. Ediciones Cagtén, 2016.

Author

Lucía Nieves Cortés is a puertorican artist and goldsmith currently based in Santiago de Chile. She studied goldsmithing and jewellery design at the Staatliche Zeichenakademie in Hanau, Germany and is a jewellery teacher at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Aplicadas in Santiago. Her studio work has been devoted to transmitting the values of joy and colour of her native tropics. She has lectured about the practice of jewellery making and wearing in Puerto Rico, Chile and Germany. The Botanical Alliances ring series, awarded with the Sello de Excelencia a la Artesanía 2020, are now part of the collection of the Museo de Artes Populares of Chile.

Lucía Nieves Cortés is a puertorican artist and goldsmith currently based in Santiago de Chile. She studied goldsmithing and jewellery design at the Staatliche Zeichenakademie in Hanau, Germany and is a jewellery teacher at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Aplicadas in Santiago. Her studio work has been devoted to transmitting the values of joy and colour of her native tropics. She has lectured about the practice of jewellery making and wearing in Puerto Rico, Chile and Germany. The Botanical Alliances ring series, awarded with the Sello de Excelencia a la Artesanía 2020, are now part of the collection of the Museo de Artes Populares of Chile.

Comments

So eye opening – absolutely loved reading this.